‘Progress’ as the meaning of history consists in development and the growth in the overall ‘happiness’ of humanity. Although development and progress today are very much considered old, worn-out concepts by many on both the left and the right of the political spectrum, the word ‘progress’ is still generally considered a positive term, denoting a supposedly desirable societal outcome, or at least a process (albeit one lacking an endpoint). On the one hand, progress can be considered as a social or state form, shape or character that occurs at the ‘end’ of an—alleged—developmental sequence. It can mean a specific socio-political ‘character’ towards which certain tendencies—implicitly or explicitly appearing in history—are already directed, and its hindrances would result in the overall ‘underdevelopment’ of humanity in the initial phases of human history. Traditional, hierarchical and ‘static’ social forms for example are often critiqued as impediments to progress. This ‘developmentalist’ meaning is sometimes associated with a ‘development open to infinity’ as ‘the end of history.’ Although metanarratives are supposed to disappear in postmodernity, and few political and social thinkers seriously believe that humanity as a whole is ‘progressing’, the belief in progress is still very common. However rare explicit progressivism, the professed ‘belief in Progress’, is today, with interest in the ‘Great Words’ having waned by the late 20th century as non-pragmatical, ‘idealistic’ and ‘abstract’ conceptions, catchwords such as ‘innovation’ are still associated with very positive meanings.

Within the mainstream of ‘progressivists’ there is much talk now of ‘Sustainable Development’ as a placeholder for Progress, as a covert admission that so-called development can also lead to premature death of civilization. However, to be explicitly ‘non-progressionist’—especially in the mainstream of political-related thinking—is still associated with lack of creativity, a lack of ‘openness’ and even a ‘retrograde’ (i.e. narrow-minded) attitude. One must perpetually change, moving between careers, relationships and geographic localities, and personalities who strive for permanence are deemed not cognitively flexible, hence, in a sense, pathologizable. The overall thinking about human society and history is still progressive, albeit often without realizing it.

Personalities who strive for permanence are deemed not cognitively flexible, hence, in a sense, pathologizable

According to well-known contemporary liberal progressivist thinkers like Francis Fukuyama the final stage of Progress could be the world hegemony of liberal democracy; Marxists and (Comtian) positivists also speak about ‘stages’ and ‘Laws’ which point to a an almost inevitable ‘final stage’, in which the problems of humanity will be ‘solved.’ Others, not explicitly philosophers, such as the psychologist Steven Pinker, like to talk about progression as a historical process which, at an initial state, was characterized by social and political oppression (‘lack of democracy’), ignorance, savagery, lack of hygiene, low average age or other possible ‘immaturity’ of material living conditions, and is heading towards a more positive outcome. As Pinker put it:

‘Life before the Enlightenment was darkened by starvation, plagues, superstitions, maternal and infant mortality, marauding knight-warlords, sadistic torture-executions, slavery, witch hunts, and genocidal crusades, conquests, and wars of religion. Good riddance…as ingenuity and sympathy have been applied to the human condition, life has gotten longer, healthier, richer, safer, happier, freer, smarter, deeper, and more interesting. Problems remain, but problems are inevitable.’[1]

As a matter of fact, not all ideologues of ‘progressivism’ are so extremely negative regarding the evaluation of pre-modern eras. The process of modernity, say the more cautious ones, such as the proponents of the so-called ‘Whig-narrative of history’ (such as British classical liberals) can be characterized by a slowly rising education, moral and civilizational rise, which lasts from the prehistoric age of mankind and antiquity to the Middle Ages and the present day. More broadly speaking, we may identify a Whig narrative of history at work whenever there is talk about ‘how far we have come’ and ‘how much more must be done.’

Contrary to philosophical speculations about its nature, so-called progress is by no means a certain ‘scientific fact.’

Neither is it self-evident that progress, if it exists at all, ought to be considered desirable.

From a non-progressive perspective, the philosophy of history, knowing and evaluating the main line of events of ‘contemporary’ history—meaning not only the par excellence contemporary world, but also the last 200-250 years—and acknowledging the general standard of today’s culture, politics, art, society and political regimes, and their main aspirations, the same facts that progressivists usually refer to can be interpreted differently.

If we are able to dispense with the idea (or preconception) of ‘inevitable development’, which became a popular European science after the second half of the 19th century—primarily related to the biological ‘progress’ of the human race, ‘becoming human’ (evolution) and secondarily, also in relation to changes in socio-political structure (called: social progress)—we find very little of the meaning of history understood in the sense of an overall ‘progression.’

The main question is: what must we consider ‘development?’ Technical progress is factual. But if we consider the ‘measure of the degree of development’ of a given human society not as its technical progress, but as something else, we will not find the sense that the representatives of progressive views have been writing about for at least two and a half three centuries—since the beginning of the so-called ‘Enlightenment’—writers, philosophers and natural scientists alike. On the other hand, we can find many explanatory arguments as to why the idea of ‘progress’ in a general sense applied to the human world or human nature can be considered unlikely.

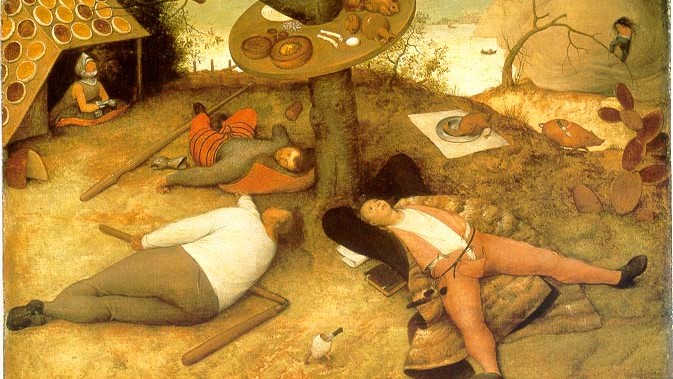

It is clear that the persuasiveness of the idea of development is closely related to the rapid change of the face of all the material spheres and aspects of human existence in the past 300 years, which of course is inseparable from developments within the mental and even spiritual realities. For the general public this is usually enough. In reality, the appearance of new technical inventions, the seemingly ‘easier’ nature of everyday life, is sufficient proof of ‘overall’ development only for those who consider physical pleasure and mostly bodily ‘well-being’, comfort and safety to be the most important factors of human life.[2] This approach can be understand as a non-ideological, ‘practical materialism’ or ‘pragmatistic conformism.’ However, in terms of long-term effects, even these aspects can be very misleading.

To highlight a typical example, the short-term advantages and long-term disadvantages of technological progress can be compared to harnessing rivers. The short-term practical and economic advantage of harnessing a river is obvious: people gain arable land, by the disappearance of such ‘useless’ things as a vast floodplain forest or a marshland. The long-term disadvantages will only be visible later, as happened for example in the case of the Great Hungarian Plains: complete drying occurs, the appearance of the countryside becomes bleak, the former biodiversity disappears, and the river, squeezed between too narrow dams, threatens populated areas with floods every year. The same can be said about the destruction of forests for timber: both fit into the process of technical progress, as rationalization and a utilitarian approach make the world more transparent and controllable, while the long-term consequence is the complete separation of humans from nature, which makes them vulnerable to their own technique—and the overturning of the earth’s oxygen balance. Technical progress apparently produces such negative results in all areas, from the construction of highways—fragmentation of ecological niches—to the installation of factories; adverse effects which, of course, cannot be eliminated by the introduction of ‘e-mobility’ or geoengineering as technological quick-fixes.

The usually one-sidedly technical solutions of modern science and technology, and in close connection to this, the constant exposure to the effects of the metropolitan lifestyle and an ever-changing environment, can be matters of debate and have indeed been in the past. However, the voices supporting the pragmatic short-term advantages have always been louder than those of the sceptics, who have been sometimes labelled as ‘bigoted’ or in extreme cases ‘enemies of humanity.’ Ecomodernism, with its promise of preserving our modern, comfortable standard of living, is more attractive than the prospect of asceticism or a radical reduction of living standards and related expectations.

Ecomodernism, with its promise of preserving our modern, comfortable standard of living, is more attractive than the prospect of asceticism

One of the most frequent topics of our present era—after nearly three centuries of ‘Progress’—is crisis: health, demographic, industrial, economic, technical, geopolitical, and above all, the above-mentioned ecological crisis. For this reason, for sceptics of modernity, it seems today quite strange to speak about a truly ‘progressive’ age. Under such conditions, the idea of an ‘overall’ development seems to be illusory for them, even if the signs of a future collapse or catastrophe are not equally visible or clear to everyone.[3]

Disasters and collapses do not necessarily happen suddenly or all at once. A possible world war—a possibility of which the world is getting closer to amid the current geopolitical crisis—would of course be noticed by everyone. However, we can also speak of ‘slow poisoning’, which—as in the case of a long-term illness—is felt by the patient only when the final symptoms appear.

The ecological crisis is typically such a disease. It is much less noticeable to the masses—although it can lead to much more complete destruction than even a world war could cause—not to mention the connections that are not related to bodily determinations in the strict sense of the word, but to the state of the general level of culture (in Spenglerian sense.)

These are, above all, the aesthetic and moral aspects. Since in modern aesthetics, objective criteria of beauty have been dissolved, it cannot be justified to talk about ‘kitsch’ in a society where no accepted standards of taste exist. When standards of taste disappear, however, say the critiques, ‘bad taste’ becomes the norm. ‘De gustibus non est disputandum’, say the proponents of progress in aesthetics. Certain misgivings notwithstanding (such as Horkheimer and Adorno’s utterly impotent criticisms of the ‘culture industry’),

modern society has been successful in decomposing the distinction between ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture.

Today, what is most interesting about the moral aspect is that while the critique of the present age talks about the ‘egoism’ of modern society, and the weakening of the sense of loyalty, respect for other people and cultures, or the place of ‘honour’—as conservatives usually formulated as a criticism of the modern age and its purported ‘enlightenment’—proponents of social progress are usually not arguing about the ‘moral eminence’ of modern man (moral progress) as the moral optimists and proponents of various ‘humanisms’ did the past, but tell conservatives that they are trapped in an ‘outdated idealist’ mindset, as narrow- minded ‘moralists.’ It used to be no different in the past, they say, since all higher moral ideals are mere illusions and all morality is relative and pragmatic. It’s the same old complaining, they say, that the ‘outdated idealism’ of Socrates or Lao-tse (or Jesus Christ) formulated against their contemporaries.

If one however, tries to free oneself, first, of the constant economism, utilitarianism, and functionalism of the moderns, one should easily realize that the undeniable material enrichment from the eighteenth century was accompanied by an incredible impoverishment of the human spirit.

While, of course, there are still great achievements by the elite layers of culture in fine art, music, literature and philosophy, the general level of society is, above all, subjected to the idea of ‘consumption’, culminating in the concept of the ‘lowest common denominator.’ For the egalitarian, all opinions are acceptable and without moral, ethical and metaphysical compasses, the one who is most popular is ‘right.’ The extent to which the popularity of something can be a measure of the ‘value’ of a given phenomenon can be seen most clearly in the phenomenon of the so-called ‘entertainment industry’ or ‘culture industry’ (Adorno) one of the most striking features of contemporary ‘Capitalistic’ societies. Regarding form of arts, that can be considered popular in terms of the current state of culture, and the least perceived by the masses not just the ‘elites’ it is enough to mention here music. At its most degrading level, such is the phenomenon of ‘music’ that is constantly turned on in the background of malls and shopping centres, as an ‘incentive to buy’ but the phenomenon is related to modern popular music or ‘electronic dance music’ in general, which, by its striking shallow primitiveness (not in terms of the individual prominent authors, but of its general trend) remains profoundly inferior in all respects to classical or folk music—or even of the music created by the so-called ‘beat culture.’ As Theodore Adorno writes: ‘Capitalist production so confines them, body and soul, that they fall helpless victims to what is offered them.’[4] ‘The same thing is offered to everybody by the standardized production of consumption goods.’[5] Indeed, scientific research has shown that popular music has overall done the same since the 1970s.

There is no doubt that while the organization of human societies reached an unprecedented level of organization by the beginning of the 21st century, with the growth of welfare institutions, the power of the state—directly and indirectly—over the individual and its organic communities has increased significantly. As Kuehnelt-Leddihn puts it: between the increasingly complex informational, technical and scientific apparatus of the modern world, and the complicated system of conditions for maintaining skyrocketing consumption, the gap is constantly growing between the ‘known things’ (scita) and among those that ‘ought to be known’ (scienda)[6] and the average person actually has no idea which ‘expert’ to listen to.

Hopes regarding general education are the least able to bridge the situation. In a globally mediatized world, education—no matter how high-quality it may be (which is usually not the case) —is far from sufficient to counterbalance the power of the ‘manufactured’ ideological constructions that reach young people, whose consciousness is the most malleable, through various channels of the Internet and popular movies and series.[7] The announcement of the agenda of the ‘fourth industrial revolution’ and ‘digitalization’ by technocratic minded, progressivist elite is closely related to the spirit of ‘consciousness formation’, and fits well into the overall logic of rationalization and rationalism. The world is becoming more and more virtual, technology is becoming more and more perfect, as the total—totalitarian—new mechanism of consumption and control prevail. Consumption and control are organically related: if the human person is seen above all as a ‘consumer’—as is the case in current ‘capitalism’—it means the lowering all artistic and moral, intellectual and ethical standards.

So why do authors like Pinker still talk about progress today? The idea of progress, that is, the intellectual idea of progress, which is not created by the ever-present welfare needs of the masses, but by rational construction, in the minds of ‘intellectuals’, can be traced back to completely different foundations as ‘facts.’

What can be the measure of the development of society if we leave aside the development of technical civilization? This is difficult, perhaps impossible to answer. Although the process of ad hoc development is not completely excluded, in history we tend to see only short flourishing periods and they are not ‘progressive’ in all respects. A nomadic person (in the distant past) without houses and material civilization, who has a solid metaphysical worldview, can feel much closer to his gods and live a much more ‘significant’ life, fitting into his own world, than a secularized Western person.

The fact that Jesus Christ is the only saviour and redeemer in Christianity suggests an unrepeatable time plane, realized during the unfolding of the ‘Divine plan.’ This is the time projected onto the historical world, the ‘highlighted time’ (Mircea Eliade). We can rightly say that Christianity almost perfectly transformed and changed the old approach of the European societies to time, and with it the evaluation of the historical world, of historicity.[8]

Such a conception of time was integrated into the layer that can be called the ‘collective subconscious’, using a term borrowed from Jungian psychoanalysis, from which, starting from the Renaissance, the various theories of development and progress as intellectual constructions emerged. However, the collective unconscious – largely rejecting the idea of transcendence as regarding an ‘average’ person in the ‘Western’ world, – is no longer Christian today. We can say the modern idea of ‘Progress’ is a secularised (desacralized) and ‘banalized’ version of the original Christian idea of ‘redemption.’

We are therefore dealing with a secularized Christian philosophy of history at the fundament of every modern conception of progress, be it romantic, ‘enlightened’ (rationalistic) liberal-democratic or communist. Russian philosopher of history, Nikolai Berdyaev says for good reason that the modern Western man cannot break away from that religion in which he is already unable to really believe as a collective.[9] Be it individual redemption or collective justification, the historical unfolding in the sense of the ‘Kingdom of God’, the various, secularized ideologies of progress (such as Marxism and Leninism, for example) came from the original Christian concept of the Apocalypse that they, in a sense, ‘distilled.’

According to the main line of progressivists, the struggles of history lead to a just or more just society, just as science eventually overcomes ‘superstition’. Ironically, today’s supporters of the ideology of progress are often those post-Christian materialists who believe that religion, as Richard Dawkins, who criticizes religion on the basis of ‘Science’ (scientism) says, is also nothing more than a kind of ‘superstition’ even if this superstition is somewhat more complex, has moral lessons and has contributed constructively to ‘the democratic roots of Europe’. On the other hand, we can find many explanatory arguments as to why the idea of progress in a general sense applied to the human world or human nature can actually be considered a superstition—that is, a contra-factual idea that is completely opposed to the self-image of modern natural scientific thought.

The propagandists or blind believers of progress—whether they are enthusiastic supporters of the meaning of history or angry opponents—essentially start from the same limited perspective: since they deny the concept of God and transcendence ab ovo, for them there is nothing but time. However, time—if there is nothing ‘above’ time—ultimately always works against humanity.

[1] Steven Pinker, Enligthenment Now, Viking, New York, 2018, 442.

[2] The famous Maslow-pyramid from the realm of psychology is routinely depicted in a truncated form, with the peak of the pyramid—the need for self-transcendence—surgically removed.

[3] Naturally, it can be said that ‘every age is an age of crisis’, but it is impossible to judge other ages as directly as we do our own. At the same time, the crisis can also be permanent, something that goes on throughout history—just as, according to its believers, ‘progress’ can also be slow and permanent. In the age of Hesiod or in the age of the early Christian philosophers, the Gnostics, or in the age of Lao-tse in China, thinkers also spoke about the ‘crisis’ of their age. As Béla Hamvas wrote almost 100 years before the present day in an essay on crisis literature, titled ‘The world-crisis’: ‘The literature of the crisis can take the position that there is a crisis. The observer of crisis-literature must necessarily take the position that the writers may be wrong, and must always maintain the possibility that there is actually no crisis at all.’ Although later in the essay Hamvas also spoke about an exceptional crisis of modernity, which is the overall crisis of religion and religiosity. See Béla Hamvas, ‘A világválság,’ https://mek.oszk.hu/05900/05945/html/, accessed 13 June 2023.

[4] Quoted in Dan Laughey, Key Themes in Media Theory, Open University Press, 2007, 123

[5] Quoted in Andrew Arato, Eike Gephart (eds.), The Essential Frankfurt School Reader, New York, Continuum, 1982, 280.

[6] Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn, Liberty or Equality. The challenge of our time. The Caxton Printers Ltd. Caldwell, 1952. 278.

[7] The most striking example of this is the US streaming service Netflix.

[8] See Mircea Eliade, The Myth of the Eternal Return

[9] See e.g. Nicolai Berdyaev, Oswald Spengler and the Decline of Europe (1922) and The Meaning of History (1923; 1936)