This article was published in Vol. 3 No. 1 of the print edition.

The consensus amongst liberals in the 1990s and, arguably, since Adam Smith, was a belief in the ‘de-territorialization’ of the world. This was the belief that globalization was a force for good, an economic version of Christendom, and that the invisible hand of the market would produce benefits on a global scale. Humanity has begun to realize, however, that globalization, rather than liberating the biopolitics of the world, has produced a win-win for a ‘knowledge class’, which is the antithesis of neo-liberalism.

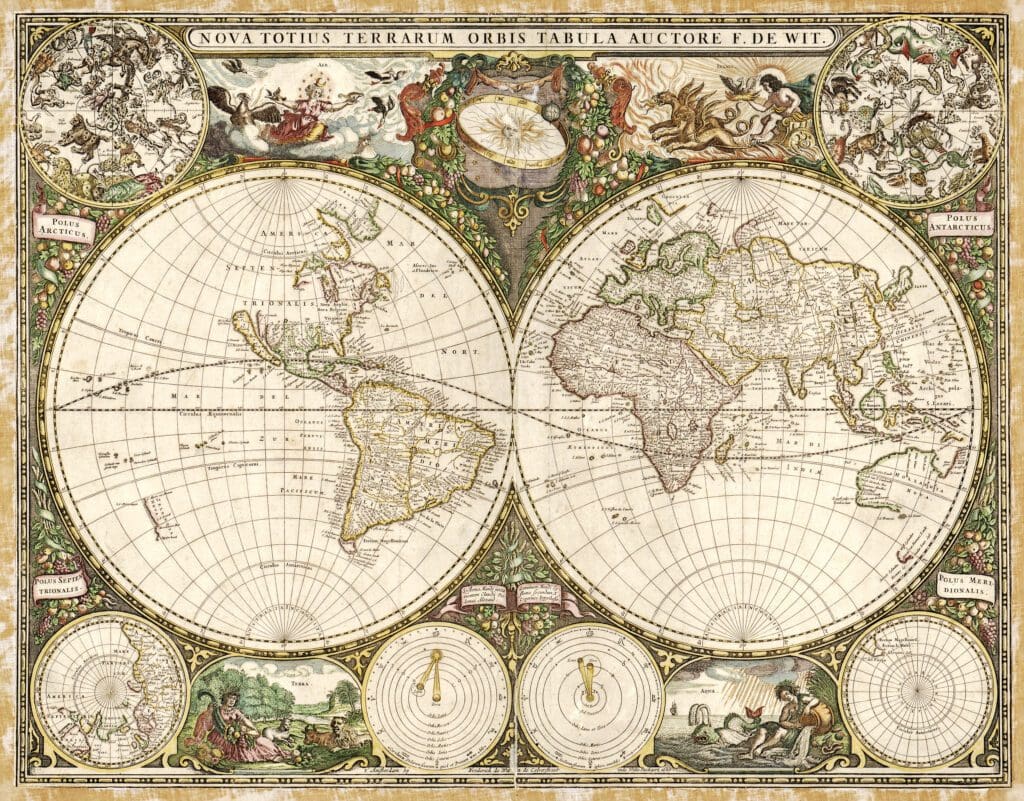

The existing Nomos of the earth, rather than being of economic determinacy, is ‘value’-driven. The liberal credo is one of using human capital, not in the sense of a Marxian surplus value exploitation in the factory, but an all-encompassing one-dimensional ordering, where the ‘political’ enters all aspects of life. Each historical epoch has a Katechon, the power to hold back the tide of the Antichrist, and this, having been Christianity, is now the ‘corporate-state elite-university’ complex, liberalism being the ‘moral’ successor to Christianity. The Roman Empire, under Christianity, became a Katechon—to preserve God’s realm from being delivered to the Antichrist. Likewise, the ‘Age of Discovery’ and Columbus’s journey to the New World were, ostensibly, a means to protect the Christian Empire from the threat of Islam—their ‘Antichrist’. Carl Schmitt,1 writing after the Second World War, believed the era of Europe was over and that liberal democracy had ‘economized’ the state. Consequently, the Nomos became the neoliberal extension of the economized liberal democratic state towards global hegemony, through globalization. The Antichrist was anything which opposed it—whether Islam or revolution. However, the realities of a globalized world and the basis of the new Nomos—a resource-based convergence of civilizational states—has reversed this process.

‘The essential problem of liberalism lies in its lack of cultural consensus; liberalism has become a melting pot of contradiction’

In the nineteenth century, in ‘Dover Beach’, the poet Matthew Arnold lamented the ebbing of the sea of faith which had ceased caressing the shores of the world. Now there is only ‘the melancholy, long, withdrawing roar, retreating, to the breath of the night-wind’.2 This ebbing tide was replaced by liberal humanism, then neo-liberalism. The Nomos of the earth derives from the Greek word meaning the law governing the settling of land, the cultivation of land, and the extraction of profits from the land. This Grossraum, as Carl Schmitt3 called it, encompassed not the maps of nation-states, but the area of resource determination. Consequently, the idea of ‘civilizational states’ becomes the Nomos which is surrounded by the embryonic international law. The nation-state replaced the historical era of the empire, from imperial Rome to the Republica Christiana. It could be seen that the modern era of the neo-liberal world represents a form of Grossraum. For what pervades a Grossraum, or perhaps a civilizational state, is its homogeneity. In fact, the new Nomos of the world will depend on the titanic struggle between the two concepts: firstly the nation-state in a globalized economic bloc and, secondly, the empire building Grossraum or civilizational state. Schmitt had predicted the differentiated Grossraum of competing empires, and this can be seen in the resource competition areas of land, sea, air, and technology. Technology and cyberspace are the new realms in which the Grossraum is controlled and policed.

The re-emergence of empire-building civilizational states is concomitant with and engineered by its opposite: the dissonant and heterogeneous fragility of the liberal democratic model. The reason for the splintering of the liberal diaspora is fourfold. The telos of the ‘Republica Christiana’ was replaced by a secular credo of ‘individualism’ in a sea of anonymity. It stresses free speech and ‘rights’ although these are increasingly constricted, but, regardless, they represent negative possibilities and no cultural consensus. This has been accelerated in the modern era as human capital is further deracinated from its social and cultural environment—the individual is uprooted and homesick.

The recent movement of democratic states such as Sweden and Italy towards a traditional, family-oriented consensus has shown itself as directly opposing the diversity model of the EU. Therein lies the second contradiction of the liberal democratic model—the ‘democratic’ aspect is destructional, in that a majority populist vote (i.e., a democratic one such as Italy’s) is devouring ‘representative’ liberal democracy, Kronos-like, from within. In the liberal elites’ model of representative democracy, however, only votes which remain within the liberal spectrum are respected or even tolerated. In a utilitarian sense, liberalism has become dysfunctional. The third reason is that liberalism also must be understood, not as a neo-liberal economic philosophy, but for what it is—a ‘revaluation of all values’.4 Liberalism, as the moral successor to Christianity, has inverted itself. Since the English Revolution and Cromwell, the economic has determined the political, i.e. the representation of powers and interests. But now the new need for liberal global legitimacy has produced a ‘corporate-state elite-university’ knowledge class—a ‘clerkdom’ of liberalism. They do not produce or manufacture, but administer a values-based system at odds with practical or populist populations. It is the final stage of Kantian morality, transformed into practical reason. The value hierarchies of regimes, of Cromwell (the ‘Protectorate’), Robespierre (the ‘incorruptible’), Marxism (‘equality’) becomes, for modern liberalism, a religion of ephemeral ‘rights’ and the ‘market’. However, it is the ‘Hollow Men’, the profound ‘Wasteland’ of anomie and masses of isolated individuals. As Zarathustra lamented:

‘Free, do you call yourself? Then I would hear your ruling thought, and not merely that you have escaped from a yoke. Are you one of those who had the right to escape from a yoke? Many a one cast away his last worth when he has cast away his servitude. Free from what? What does that matter to Zarathustra! But your fiery eyes should tell me: free for what?’5

Finally, the nation-states of Europe display a schism between the ‘culture’ state and the ‘liberal’ state. Nations such as the United Kingdom and France profess liberal ideals: global human rights, globalization, immigration, and ethnic pluralities. By contrast, the likes of Italy and Germany are traditionally ‘homogenous’ and national culture is the underlying leitmotif. This creates a splintering of tendencies bubbling to the surface in the brackish waters of liberalism.

The new Nomos of the earth sweeps up the night winds and ushers in another era. In this new epoch, notions of left and right become exposed as the veil of mist falls. The interregnum of the new Nomos is what political scientists call ‘transversal politics’. In this, the real divisions of the liberal world, a heterotopia of working class/knowledge class and metropolitan/rural, turns nations towards local autonomy and tradition. Europe coalesces in an uneasy return to a nation-state Grossraum of differentiated states. The European Union becomes more and more superfluous and the embodiment of the hypocrisy of superficial, privileged ‘progress’ for the trahison des clercs of the knowledge class. The world coalesces into competing blocks in the acquiring of Nomos and resources. It is visible in the clash of ‘liberal’ and ‘civilizational’ states, a struggle which was obscured by the Cold War. There is no consensus on the Katechon or the nature of the Antichrist; essentially, as the ideological debate has been relegated to the background in a sophistic dialogue monopolized by the tempest of progress on the one hand and technological apathy on the other.

‘The rise in “populism” is a defence against assimilation and an assertion of a resistance to the hegemony of the West’

These tensions are echoed in certain geopolitical ramifications. Whilst the US worked as a balancer during the Cold War, the realization on the part of China and Russia has been that, in the domain of resource scarcities, the Leviathan is king. This process has been ongoing and is pushing out the boundaries of the Grossraum—its manifestation in Russian and Chinese assertions. The new Grossraum, predicted by Schmitt, will be fought over a new, fourth aspect of the traditional Grossraum. To land, sea, and air has been added a new domain—that of cyberspace. Cyberspace would favour the hegemony of the English language, and hence American dominion over this. However, this is changing, as Chinese and other languages carve out their niches and expand their diasporas. The essential problem of liberalism lies in its lack of cultural consensus; liberalism has become a melting pot of contradiction. Diversity is not the glue of homogeneity, irrespective of its merits and demerits. The Völkerwanderung or Age of Migrations, which took place between the fourth and ninth centuries, changed the nature of Europe, leading to the fall of the Roman Empire and to mass migration into Europe. The causes of the Völkerwanderung are still debated, but seem to have been due to climate change and population pressures from the east (the Great Wall of China producing a tidal wave of movement). If the ‘cosmopolitanism’ of the Roman Empire could be viewed through a modern lens, and the pressures magnified exponentially, then the weaknesses of Western states, with their cultural dispersion, would appear clearly.

American unity is based on the supposition of external threat; this is a bulwark of national unity. The Cold War and Islam were the external dangers which solidified the state; the centralization of the US state, through massive spending on a military budget and expansive state sectors, has further antagonized the ‘populist’ base. In fact, it is the dislocation of working class people from centralized bureaucracies which is facilitating the new grassroots democratic surges in Italy, Sweden, etc. Although the liberal media wishes to frame the new ‘populism’ in chauvinistic language, the reality is a concerning illumination of liberal democratic contradictions. States such as China and India emphasize an economic and cultural diaspora, but not on the basis of integration into American globalization. They are separate civilizational states with homogeneous cultural subjects. The nation-state not based on cultural consensus will be thrown into the graveyard of aristocracies.

There is nothing unusual in the success of civilizational culture states. Historically they have been successful in forging expansive realms. Bismarck’s Prussia, with its blood, iron, and social insurance, the Zollverein or customs union, became the Germanic model, and led to the unification of the German states. This framework was never ‘universalized’ or exported, it was culturally specific. So, the globalized liberal order was attempting to impose a universal system, a system of ‘negative’ values, i.e., democracy, rights, and tolerance. But, in this, there is no prescription for how to live; it is the opposite of a political theology. Universal utopia paid lip service to local customs and culture, with the main player ostensibly being global capital and access to markets. The rise in ‘populism’ is a defence against assimilation and an assertion of a resistance to the hegemony of the West. The reason for conflict between the universal liberal world and ‘civilizational states’ is that, due to technology, states increasingly confront one another over resources and scarcity. There is one option for Europe, or a federation of Europe, and that would be to adopt a Nietzschean model of a great Europe; in effect, a civilizational bloc of its own, but culturally contained, and without the abstract rules, universalism, and liberal fetishes of the EU. It would need to rediscover itself in a Westphalian system of principalities, within a Schmittian legal framework.

History has given people some sense of belonging and security; it meant the medieval castle protecting the commons from barbarians. It meant the Catholic cathedral as the solid fortress against the devil. In the modern age, the factory became the repository of communal wealth, the Protestant work ethic a bulwark against idleness. However, the tides of faith and labour have long since withdrawn down the shingle beach. The ‘corporate-state elite-university’ class are invisible, and the teleology of the modern too diverse, too alienated through technology. The individual walks alone in the wasteland. What ‘populism’ means is a nascent exasperation over the lack of real participatory democracy and the lack of accountability of large groups of knowledge class members and the new technological state. A new populism is appearing, based on real participatory federalism oriented towards tradition and community, with the Nomos being grounded in the ethnic divisions of states and regions. A federal, territorial solution satisfies peripheral groups, and avoids the universalism and forced diversity of liberal statist democracies. A spectre is haunting Western liberal democracies, and it is not the spectre of communism. It is the spectre of ‘populism’.

NOTES

1 Carl Schmitt, The Nomos of the Earth in the International Law of the Jus Publikum Europaeum (New York: Telos Press Publishing, 2006).

2 Matthew Arnold, Dover Beach (Clinker Press, 2008).

3 Schmitt, The Nomos of the Earth.

4 Friedrich Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols, trans. Thomas Common (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2019).

5 Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, trans. Thomas Common (Blacksburg, VA: Wilder Publications, Thrifty Books, 2009).

Related articles: