The Hungarian Peasant Uprising led by György Dózsa, a little-known Szekler gallant, lasted only a few months between April and June 1514, but it has nevertheless gone down in Hungarian history as a bloody event.[1]

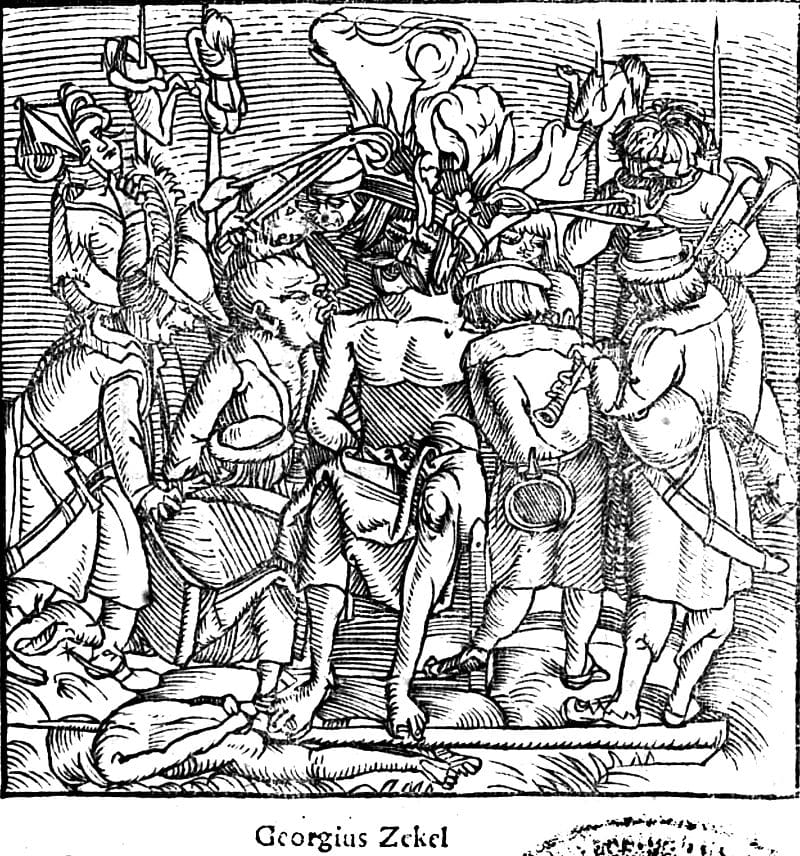

This year marked 110 years since Pope Leo X appointed his former rival, Archbishop Tamás Bakócz of Esztergom, as the papal legate of a crusade against the Ottomans in Northern, Central, and Eastern Europe. However, they could not secure the supply of the 10,000–20,000 army gathered for the campaign organised from April 1514, typically made up of serfs, thus it had to be suspended at the end of May. The anger of the participants, however, turned against the feudal aristocracy, and the campaign that started out as a crusade soon turned into an anti-feudal rebellion. The radicalised peasants were eventually defeated by the royal army returning from the Turkish front, and its leader, György Dózsa was executed as a traitor: with a fiery crown placed on his head, he was quartered.

The inclusion of the Peasant Uprising into the Hungarian historical pantheon was already done by the humanist writers in the decades following the events. Dózsa’s figure and the uprising were magnified—he was portrayed as a kind of anti-hero, but some sympathy was shown for his fate as well. Besides, to the considerable satisfaction of Communist historiography, an anti-clerical emphasis could also very soon be detected in the sources, which were then further enriched by ideas based on the Protestant view of history, especially with the ideas badmouthing the Pope.

But Dózsa’s figure was not included in the national historical discourse until the middle of the 19th century. At that time, during the emancipation of serfs and then during the agrarian reforms, his image became a symbol of the changes, which is also confirmed by Baron József Eötvös’s great novel titled Hungary in 1514.[2]

After a short interlude in 1919, the turning point in Dózsa’s re-evaluation took place in 1945, when

the left-wing parties, but above all the National Peasant Party, declared the peasant their historical role model.

The principal figures and intellectuals of the Party, such as Péter Veres, Gyula Illyés, Ferenc Erdei, and József Darvas, created a real cult around the figure of Dózsa, and, at the same time, the Communists coming home from Moscow also brought their own positive image of Dózsa with them. The work of Sándor Gergely, a former journalist from Moscow and the President and later a presidency member of the Hungarian Writers’ Association, who brilliantly visualised a domestic and international political conspiracy, became the Dózsa novel with the largest number of copies ever published, the impact of which could only be rivalled by Hungarian writer, literary historian, and head of the Hungarian Film Production István Nemeskürty’s work from 1972.

Soon after 1945, dozens of public areas in Budapest and the countryside were named after Dózsa, and from 1950 to 1990, one of the most popular football clubs bore the name of the gallant, too. In addition, Dózsa’s portrait also appeared on the forint banknote series issued in 1947 and later on the reverse side of the twenty-forint coins as well. In the Middle Ages, the most important means of propaganda was said to be the ruler’s portrait struck on coins—it seems, however, that this practice, mutatis mutandis, has not completely lost its validity even in the modern ages.

However, the Communists dispossessed the Peasant Party of Dózsa very quickly. As Mátyás Rákosi, head of the Hungarian Communist Party, put it, ‘we particularly preserve and cherish the historical traditions that are connected with our working people. That’s why we have revived the memory of György Dózsa, who has been reproached and defamed for such a long time.’[3] Back in 1925, Rákosi had already compared his own trial to that of Dózsa’s in his plea: ‘It was a lawsuit of the poor peasantry, who had bled thousands and thousands of times for the sake of the Magyars, against the idle landowners who had been in cahoots with the Habsburgs for half a millennium, and who shirked all responsibilities and burdens.’[4]

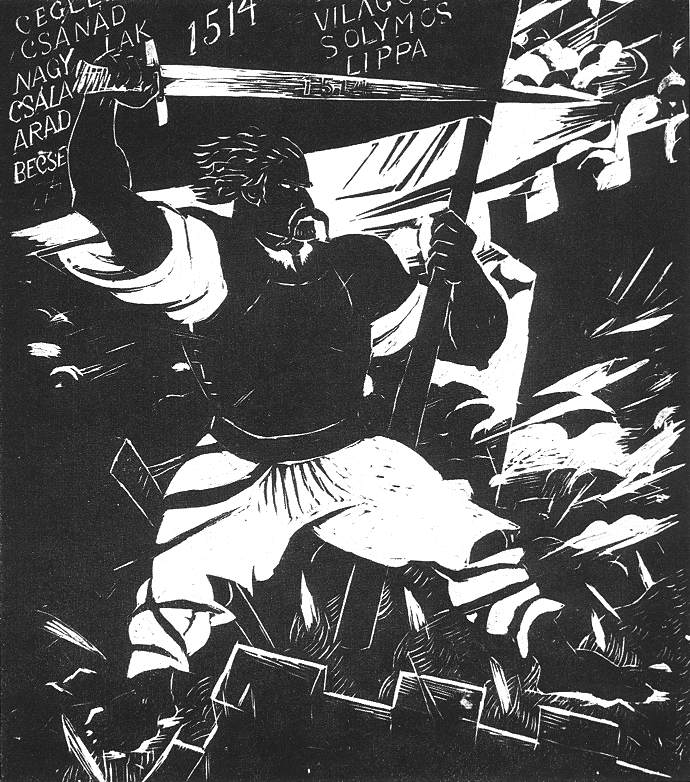

In the canon of political celebrations, Dózsa found a solid place next to János Hunyadi, together with whom he was the only one from the centuries before 1526 to fit into the concept of the ‘advanced traditions’ tolerated by the Party. The concept developed by József Révai, the leading ideologue of Hungarian cultural life from 1948 to 1953, combined the elements of the folk traditions about Dózsa, the legacy of Rákóczi’s War of Independence and the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 with communist ideals. It is therefore not by chance that an engraving depicting György Dózsa made by Hungarian painter Gyula Derkovits was also placed on the cover of historian Aladár Mód’s book titled 400 Years of Struggle for an Independent Hungary, first published in 1943: it suggested that the fight against foreign imperialism dates back to Dózsa’s uprising.

The communist propaganda wanted not only to make the ‘advanced traditions’ to be read, but also to be seen.

In one of his speeches in 1950, József Révai, for example, lamented the lack of contemporary historical painting. A big event of the 1952 Hungarian Fine Arts Exhibition was a tableau entitled Before the Storm, which had picked the peasant uprising as its subject. Typically, Rákosi did not like the dark tone of the picture (as he apparently remarked, ‘not bad, not bad, but why is it so dark?’), and Márton Horváth, another well-known figure of Communist cultural policy, missed the eye contact between the leader and his soldiers in the picture, since, in his opinion, they do not look at their leader.[5]

The tender for the Dózsa statue in central Budapest was launched in 1953 on the occasion of the 440th anniversary of the Hungarian Peasant Uprising, but after all, the 1956 Revolution discouraged the Government from erecting the idol. Some analyses see the Revolution’s desire for freedom and the fresh experience of retaliation appearing in the post-1956 versions of the image of Dózsa, certainly not without reason. This was also given actuality by the fact that, contrary to Communist propaganda, the largest retaliation in Hungarian history was not brought about by 1514, but by the years following 1956, which truly affected a significant proportion of Hungarian society in one way or another.

After all, only in 1961 did the system feel strong enough to erect a ‘revolutionary’ monument on Dózsa György Square below the Royal Palace in the Buda Castle District. The monstrous size of the memorial not only symbolised the confidence of the new power, but was also a clear message to the ‘counter-revolutionaries’, and at the same time, with the Royal Palace in the background, it provided a sort of reinterpretation of history, too. The side figures were meant to represent the worker–peasant unity, but the statue also sent a message to the clergy by depicting a priest who has stood at the side of the insurgents and is about to rip off his cross.

During the years of the Kádár Regime’s consolidation, the authorities put much emphasis on Dózsa’s anniversary in 1972, even though the occasion itself was only trumped up, since Dózsa’s year of birth in 1472 is a mere assumption. However, contrary to the expectation of the Party and the Government, the national celebrations in 1972 brought ambivalent results and fundamentally shook the image of Dózsa, which seemed to be preserved after 1945. In breaking with the traditional image of the peasant leader, historian Jenő Szűcs stood out in particular as he questioned the anti-feudal and anti-clerical nature of the Peasant Uprising.

Then, on the new anniversary in 2014, commemorations and celebrations were much more subdued. Certain sceptical tones could already be heard in the articles published in the media, and the younger generation of historians basically rewrote the history of the Peasant Uprising. They often indicated that the medieval Kingdom of Hungary did its best to confront the Turkish threat—of course, the Hungarian elite of the time could certainly have done it better, but their performance was not worse than that of the elites of the neighbouring countries. Obviously, it is difficult to assign the role and responsibility of György Dózsa, ‘the common man’, in this process, since the crusade and the subsequent uprising in 1514 can be seen as a last hopeless attempt to solve the intractable: to eliminate the Turkish threat.

Yet, the fight against the Turks was intertwined with the eternal desire for social justice.

The Peasant Uprising had to be fought twice: once on the battlefield and then on the level of historical memory.[6] As far as historical memory goes, no one took responsibility for the failed crusade after the failure of the summer of 1514: the public opinion put all the responsibility on Archbishop Tamás Bakócz and/or on György Dózsa. The image of Dózsa in Hungary has undergone so many metamorphoses that it would be difficult to link it to a single political trend or party. He could fit in the role of a national hero who took up arms against the Turks under the banner of the Cross blessed by the Pope; a ‘martyr of the proletarian movement’; and a victim warning against the retaliation after the Revolution of 1956 all at once.

[1] Norman Housley, ‘Crusading as Social Revolt: the Hungarian Peasant Uprising of 1514’, Crusading and Warfare in Medieval and Renaissance Europe, Aldershot, 2001, pp. 11–28.

[2] József Eötvös, Magyarország 1514-ben, Pest, 1847.

[3] Mátyás Rákosi, A békéért és a szocializmus építéséért, Budapest, 1951, p. 131.

[4] Sándor Györffy (ed.), A Rákosi per, Budapest, 1950, p. 133.

[5] András Rényi, ‘“Vihar előtt”. A történeti festészet mint a sztálinizmus képzőművészetének magyar paradigmája’, in Péter György and Hedvig Turai (eds.), A művészet katonái — Sztálinizmus és kultúra, Budapest, 1992, pp. 34–43.

[6] Gabriella Erdélyi, ‘The Memory War of the Dózsa Revolt in Hungary’, in Armed Memory: Agency and Peasant Revolts in Central and Southern Europe (1450–1700), Göttingen, 2016, pp. 199–220.

Related articles: