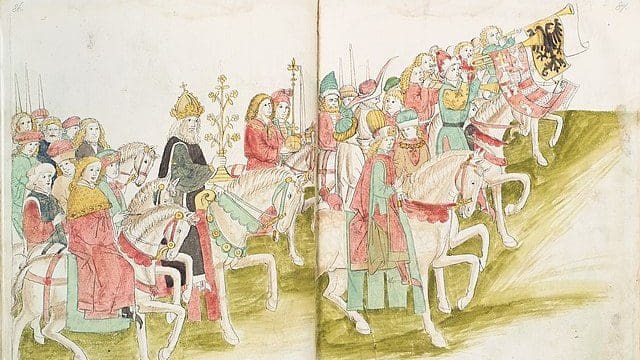

Today, 6 July 1439, marks the anniversary when the Orthodox Church of Constantinople reunited with the Church of Rome. A vital figure in this reunification was the Holy Roman Emperor and King of Hungary and Croatia Sigismund of Luxembourg (1368– 1437), ending centuries of separation.

Sigismund’s Influence in Papal Matters

Sigismund was recognised as King of Hungary in 1387[1] from his wife Queen Mary, who in turn succeeded her father Louis in 1382. He was crowned Holy Roman Emperor by Pope Eugene IV in Rome in 1433.

After Sigismund became king, his lavish lifestyle, to say nothing of his military expenses against the Ottoman Turks and the cost of his later candidacy for the imperial crown rapidly depleted the resources of the Hungarian royal treasury. His fiscal policies crushed the Hungarian peasantry with unbearable burdens of taxation and alienated the restive Hungarian aristocrats. This notwithstanding, Sigismund’s prestige in Hungary was enhanced by his position as Holy Roman emperor after 1411, more so his Placetum Regium, a decree stating that Papal bulls could not be pronounced in Hungary without the consent of the king.

In a token of his sovereignty, he presided over the two forerunning Ecumenical Councils to Florence: Constance (1414-1418) and Basle (1431).[2]

Constance sought to resolve who was the legitimate successor to St. Peter. After the papacy had returned to Rome from Avignon in 1378, some French cardinals returned to Avignon and elected two rival popes: Clement VII (1378–94) and Benedict XIII to contest the legitimacy of the reign of Urban VI (1378-1389) and his successors. To add to the confusion, there was a third claim to the Throne of St. Peter, who took the name of John XXIII (1410-1415).

Sigismund took a leading part in the deliberations,

and during the sittings travelled to France, England, and Burgundy, though in a vain attempt, to secure the abdication of the three rival popes. In any case, his being one of the driving forces behind this Council helped bring the schism to an end.

Basle addressed the question of papal supremacy, the dilemma of the Czech proto-Protestant Christian movement known as the Hussite heresy, and finally the reunion of the Western and Eastern Churches. Sigismund was instrumental in support of Martin’s successor, Eugene IV (r. 143-1447) vis-à-vis those who opposed his measures. On 15 December 1433, Eugene yielded and revoked his own decree that had dissolved the Council in 1431, and transferred the council to Ferrara, Italy, in order to consider reunion with the Greeks, i.e., the Church of Constantinople, which Sigismund, one more, was important for this.[3]

Catholic-Orthodox Separation

Officially speaking, the Orthodox-Catholic breach occurred in 1054 over the term filioque (‘and the Son”)—the dogma that the Holy Spirit proceeds from Father and Son as one Principle. Prior, both parties taught that the Holy Spirit proceeds solely from the Father, and not from the Son. The Catholic position is that just as the Holy Ghost was externally sent into the world by the Son as well as the Father (John 15, 26; Acts 2, 33), the Holy Spirit internally proceeds from both the Father and the Son in the Trinity. However,

the reality of the separation was purely political on both sides

that mutually excommunicated each other—the Apostolic Church of Alexandria had already separated itself from Rome in 451 over dispute as to the explanation on the two natures of Christ (human and divine) at the Council of Chalcedon.

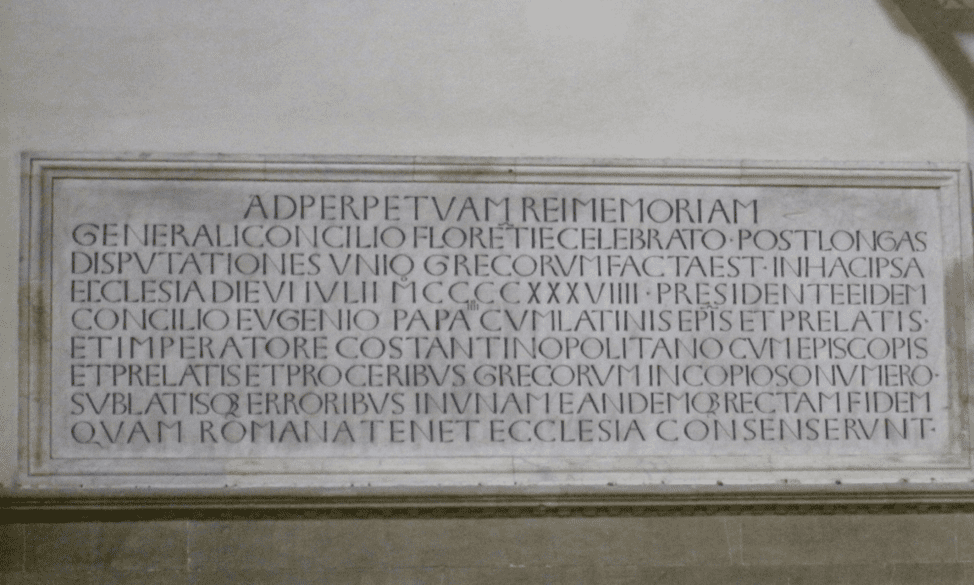

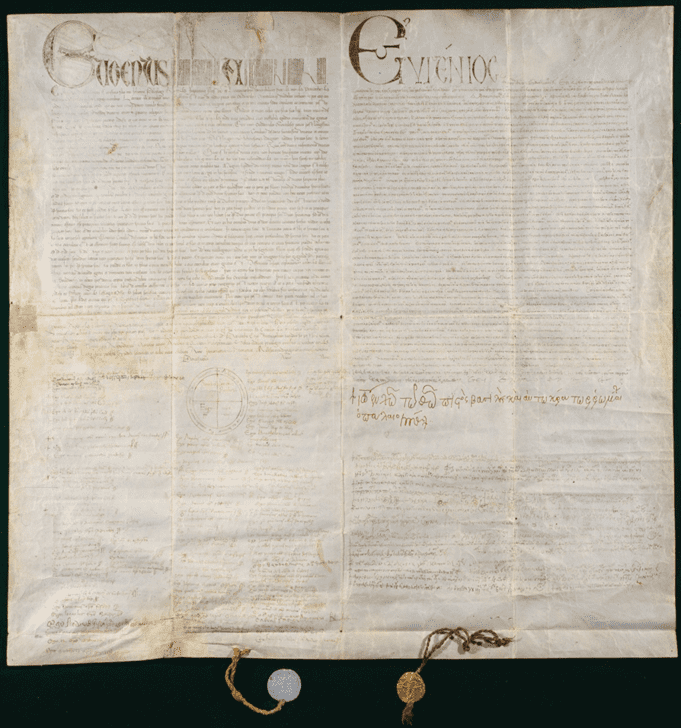

The Ecumenical Council of Florence

On 6 July 1439, in the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, Emperor John Paleologus, the Patriarch Isidore of Kyiv, and procurators of Alexandria, Jerusalem, and Antioch assisted at the Ecumenical Council of Florence in the Church of Santa Maria Novella, signed the Bull Lætantur Cæli, thus putting an official end to the Schism of 1054 and uniting the Orthodox Church with the Church of Rome—the Church of Alexandria, along with the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church temporarily rejoined in 1441.[4] Constantinople solemnly celebrated the re-union in Hagia Sophia on December 12, 1452.[5]

IN PERPETUAL MEMORY OF THE ECUMENICAL COUNCIL OF FLORENCE AFTER LONG DISPUTES THAT HAD TAKEN PLACE FOR THE SAKE OF UNITY OF THE GREEKS UNDER THE PRESENCE OF POPE EUGENE IV TOGETHER IN UNION WITH THE BISHOPS AND PRELATES OF THE LATIN CHURCH AND THE EMPEROR OF CONSTANTINOPLE WITH THE BISHOPS AND PRELATES AND THE NUMEROUS NOBLES OF THE GREEKS THE WALL OF DIVISION WAS ELIMINATED IN THIS CHURCH [CATHEDRAL OF SANTA MARIA DEL FIORE IN FLORENCE] AND THUS RECTIFIED UNDER THE ONE FAITH AS HELD AND MAINTAINED BY THE ROMAN CHURCH ON THE 6th DAY OF JULY IN THE YEAR OF OUR LORD 1439[6]

The points of division that were settled between both Churches were:

The Procession of the Holy Spirit, i.e., the Filioque. The East holds, as the West did before 1050, that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father through the Son. The West developed its explanation that the Holy Spirit not just proceeds through the Son but He also proceeds from the Father and the Son;

The use of fermented bread for consecration;

The existence of Purgatory which the East did not acknowledge at first;

The Primacy of the Bishop of Rome.

In fact, the Church of Constantinople remained in union with Rome until 1484, when a Synod held in the city completely rejected Laetantur Caeli, drafting a creed, which excluded the Filioque, to be recited by Latin converts.[7]

While it is true that the reunification of the Christian Churches was short-lived, and notwithstanding his many political failures, such as the Crusade to Nicopolis in 1396, Sigismund’s involvement as King of Hungary and as Holy Roman Emperor cannot be discounted.

[1] Unlike most monarchies, Hungary began to elect its monarchs from late fourteenth century onwards. The exception was Sigismund’s son-in-law Albert II of Habsburg who reign from 1438-1439. Cfr. Martyn Ready, The Middle Kingdoms: A new History of Central Europe. Dublin, Penguin Random House, 2023, 176.

[2] While this Council was called by Pope Martin V and “formally” closed at Lausanne in 1449, its overall validity has been questioned, despite the Catholic Church listing it as of of its twenty-one Ecumenical Councils. See “Council of Basle”, in newadvent.org (https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/02334b.htm), accessed 20 June 2023.

[3] Ready, The Middle Kingdoms, 176.

[4] Cfr. Portella, Mario Alexis, Ethiopian and Eritrean Monasticism: The Spiritual and Cultural Heritage of Two Nations. Florence, BP Editing, 2015, 112-7.

[5] Acta Slavica Concilii Florentini: Narationes et Documenta, Vol. XI. Rome, 1976, 56-67; Gino Capponi. Storia della Repubblica di Firenze. Firenze, La Spezia 1990, 13.

[6] The Patriarch of Constantinople Joseph II passed away just about a month prior to the official proclamation of unity on June 10, 1439, though he had personally signed the primary dogmatic decree on the Procession of the Holy Spirit, i.e., the Filioque, which was the formal reason for the Schism of 1054. His death was prior to the resolution on purgatory. He was laid to rest in the Church of Santa Maria Novella, where the Ecumenical Council took place. Andreas de Santacroce, Acta Latina Concilii Florentini, Vol. VI. Rome, Pontificium Institutum Orientalium Studiorum, 1955, 224-225.

[7] Cfr. Joseph Gill, S.J., The Council of Florence. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1959, 410-411.

[8] The Russian bishops refused to accept the Union with Rome. Consequently, Isidore was imprisoned in 1441 by the Tsar Vasily II. See “Isidore of Thessalonica,” newadvent.org. (https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/08188a.htm) accessed 20 June 2023.