The majority of Hungarian people know from their years spent in the classroom that the first battle of the 1848–1849 War of Independence won by the Hussars was at the Pákozd–Sukoró–Pátka ‘triangle’ on 29 September 1849. The freshly assembled Hungarian army, led by Lieutenant General János Móga, captured a surprise victory over the Ban of Croatia Jellačić’s offensive forces.

However, do we know what was the last battle won in the Hungarian fight for freedom, eventually crushed by the Habsburgs?

The last battle where the Hungarians were victorious was the Battle at Kishegyes, taking place on 14 July 1849. Kishegyes is a settlement located in the region of Délvidék (Southern Land), the southern part of the Kingdom of Hungary at the time (today, it is part of Serbia), about 40 kilometres (25 miles) south of Szabadka (Subotica). This is where our hussars took their last victory, at the border of three villages. While the clash is known as the Battle of (Kis)hegyes, two other villages nearby, Bácsfeketehegy and Szeghegy, also claim ‘possession’ of the battle. And not without merit.

The Clash of Feketić, as the locals tend to refer to it, is indeed more accurate nomenclature geographically, since the battlefield is closer to the village of Feketić. What is beyond debate, however, is that

in this fight, just like at Pákozd, we were facing Josip Jellačić, Ban of Croatia again!

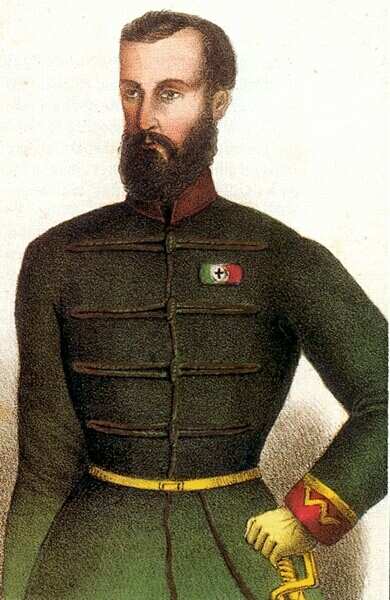

The main objective of the military campaigns taking place in Délvidék in mid-1849 was the capture and occupation of Bácska (Bačka). The Ban, fighting on the side of the Imperial Forces, was amassing victory after victory. General Richárd Guyon of Hungary, who had already distinguished himself at the Battle of Pákozd, set off to stop the Emperor’s army at the end of June. He arrived between Kishegyes, Szegyhegy, and Feketehegy on 8 July, and set up his base there. It would have been very important for him to merge with the division of the approaching General György Kmety. The battle was originally planned for 15 July. However, Jellačić was informed quite early about the movement of Guyon’s forces, and crossed the Danube–Tisa–Danube Canal on 12 July. Keeping a fast pace, he reached the outskirts of Feketić by midnight 13 July. He attacked immediately, first on the left, then on the right flank.

The Imperial troops had about 12–13 thousand men, along with 79 cannons. Guyon, on the other hand, had only 7–9 thousand men and 40 cannons. Jellačić’s plan worked, the Hungarians were caught off guard by the attack of the Ban of Croatia. The infantry regiment serving on the outpost was able to repel the first wave of attacks, while the rest of the army took formation. Richárd Guyon was able to switch from defence to offence.

The battle went on with the two sides consistently going back and forth in who had the upper hand, when Colonel Mihály Peretz carried out an attack on the right flank with heavy artillery. This shook Jellačić’s confidence in success and the Imperial Forces started to retreat. General Guyon did not hesitate:

he ordered his troops to chase down the enemy, and they were pushed out of Bácska soon after.

Despite his fast-paced march, György Kmety arrived too late to play a significant role in the battle. The Austrian side had 684 men dead or wounded, while the Hungarians had 81 men fallen and another 141 wounded. The Hungarians also captured 12 cannons and 200 prisoners of war.

The battle itself, from a military history standpoint, is notable for Ban Jellačić having taken his victory for granted because of his advantage in numbers over the enemy. ‘Let the enemy hum the last tune of the Hungarian uprising. The day of retribution is coming. My friends! Soon, like Hercules, we shall chop off the head of the Hydra!’, the overconfident Ban of Croatia declared.

Governor Lajos Kossuth thanked General Guyon for his victory in a letter, writing:

‘Please accept my and the homeland’s gratitude for your victory won on 14 July. I am looking forward to the rest of your generalship with hope, since where such a brave army is commanded by Guyon with the heart of a lion, nothing but victory can follow.’

However, the tide of history turned eventually. With the Russian Tsar’s forces, the imbalance in army sizes made it impossible for the Hungarians to win another battle. With the Surrender at Világos on 13 August, the War of Independence ended. However, the world saw once again: the Hungarian’s yearning for freedom knows no bounds, and knows no impossibility!

Related articles: