This week I partook in the mysterious Tusványos Festival (18–23 July 2023). The festival, held annually since 1990, is part politico-intellectual conference (it has academic-style panel discussions on societal topics), part rock concert, and part nature and spa retreat. Its mystery? That it makes that unlikely combination work. That it gets Hungarian villagers, students, and members of Budapest’s elites to have fun together on a field in an ethnically Hungarian part of Romania. The festival is part of Budapest’s campaign to reach out to Hungarian minority communities abroad, which would otherwise be isolated and scattered. It is set in the tiny town of Tusnádfürdő (in Romanian: Băile Tușnad) in a forested valley in Székelyföld or Szeklerland, an area inhabited by Székely Hungarians in eastern Transylvania, which is in central Romania [catches breath].

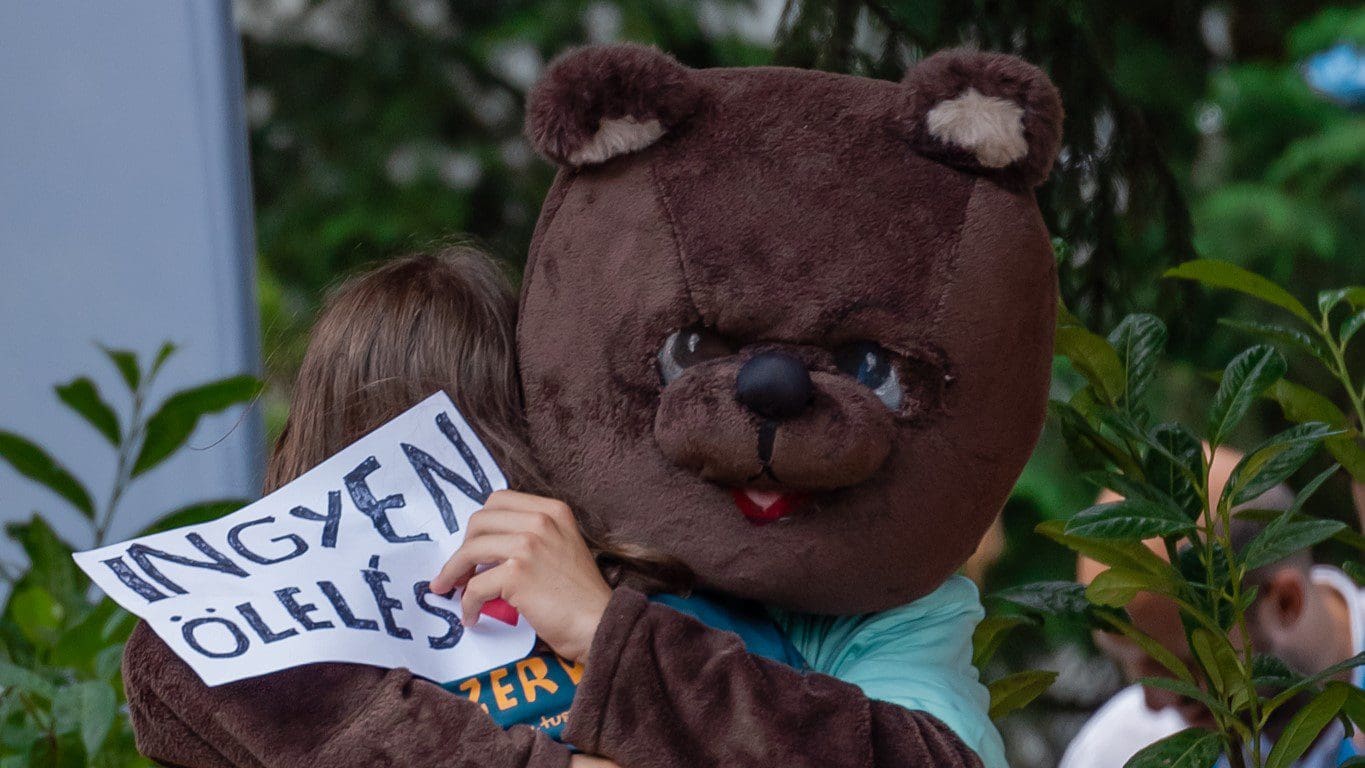

In short: I had no clue where I had ended up or what to expect. I had been bussed in, joining the Danube Institute’s scholarly delegation as a Budapest-based freshman visiting fellow from the Netherlands. Yes, I had tried to extract information from experienced Tusványos-goers before setting out from Budapest; still, they had merely confused me further by stringing together the words ‘academic panels,’ ‘rock music,’ and ‘forests with dangerous bears,’ followed up by an ominous, ‘You will see.’ An old Romanian friend from college, who was even less informed than I was about the festival’s nature, jokingly speculated that I should prepare for ‘paramilitary training.’ However, I knew that was false because my friend and Danube colleague Rod Dreher was going too, and there was no way that Rod could do fifty push-ups.

But in all seriousness: I had worried that the festival would be chauvinistic, covered in Hungarian flags and stern Magyar politicos. Nothing of the kind. To my relief, the festival was playful, lively, unpretentious, and good-natured, bringing together ethnic Hungarians from all walks of life and all parts of Hungary and Transylvania.

Democratic Culture

I must say I am impressed by the concept. I have been to many academic and political conferences with panels and talks and coffee breaks; and I have been to folksy village festivals with food stands, tents, and abysmal live bands, where elderly couples stroll about, the lads drink beer, and teenagers make out clumsily in dimly lit corners; however, never had I seen those two worlds integrated into each other, synchronically. Diplomats and think-tankers from Budapest and Hungarian community leaders from Transylvania, recreating ruralites from nearby villages and the urbane journalist and nobleman Boris Kálnoky, an American literato with leather loafers that were not supposed to get muddy and lemonade-overdosing Székely youths: all were in one place. Social distances shortened.

At one point, John O’Sullivan—the eighty-one-year-old English essayist, a former adviser to Margaret Thatcher, and president of the Danube Institute—took shelter from the rain in an improvised wine bar beneath a tent. He had been walking back to the hotel after lecturing on the history of the EU’s eastward expansion, when it began raining. I proposed a stop-over. But just when we sat down with a white and a rosé, a far-too-proximate rock band blasted out a baseline from hell, against which the tent’s canvas offered no protection. I asked John about his music preferences. While he talked about Beethoven and the Great American Songbook, I noticed some teenagers picking up books from a book stand in the back of the noise-overflooded wine tent. They were in a mini library in a wine bar at a rock concert at a political conference, sharing this odd, multitasking space with farmers, academics, and segments of Hungary’s political, diplomatic, and journalistic elites.

What was I looking at? Democratic culture.

In a democratic culture, elites and commoners are not separated by high walls but stand alongside each other—ideally, in a periphery; on a field in rural Romania, let’s say. The democratic spirit flattens social ranks by uniting people based on the most common of commonalities: belonging to a nation. To ideological ‘anti-nationalists’ from the West, I say: you may not like it, but this is what democratic culture’s peak performance looks like.

The nation celebrated at Tusványos, the Hungarian one, drapes over various states in the Carpathian Basin and consists of a plurality of ethnic and religious groups, fully including not just Christian Magyars but also Jews, Ungarndeutschen, and Roma with roots in the region. Foreign guests like me, who come from outside the Hungarian nation or family of nations, could also feel welcome, because, if devoid of chauvinism, nationhood offers fertile ground for inter-national solidarities and sympathies. You can respect members of other nations in full recognition of their foreignness and cultural differences. Such respectful recognition of difference can grow into a particularistic cosmopolitanism that cherishes or even loves concrete cultural others from a love of that which is one’s own.

Essential to outward-looking democratic nationhood is citizens sharing their interpretations of society, politics, and world affairs. Here the discussion panels came in. Placed in tents, they focused on regional development and geopolitics. Most discussions were in Hungarian. English and Romanian speakers were live translated, the translations reaching the audience via headsets.

Discussing Ukraine

The war in neighbouring Ukraine loomed large on the agenda. My panel, which reflected on the concept of a multicivilizational world, also focused mainly on Ukraine and the fateful divide between Russia and the West, despite a few China observations from my side. I was honoured to speak on a panel moderated by Anna Sikó, Hungary’s ambassador to Georgia, alongside fellow panellists István Íjgyártó, who has held ambassadorships in Russia and Ukraine, and István Balogh, Hungary’s ambassador to NATO.

After the discussion, I was approached by Dr Andrii Buzarov, a Ukrainian journalist and pr-operative for Kyiv’s military effort, who had come to the festival to rally Central-European support. He repeatedly patted me on the shoulder, twice mentioning that my home country of the Netherlands touts a seventy percent support rate for sustaining the Ukrainian war effort. Yet, I had to disappoint him; my position, as I felt obliged to clarify, was less strident than he had hoped. Though my sympathies indeed land on the side of Ukraine,

the Nord Stream debacle and the horrendous casualties suffered along the seemingly unmovable Donbas front

(as of writing) have made me rethink how those sympathies are best applied. The interests of the peoples living in Ukraine should be interpreted within the context of existing military and political conditions. After all, a wall of steel and death cannot be surmounted with morality alone, and spraying cluster bombs at it might not be the way forward either.

At this point, a ceasefire may be virtually everyone’s best bet. This, at least, is the current position of Dr Edward Luttwak, the esteemed Romania-born American geostrategist, who we recently had on the Buda Hills podcast, which I co-present with philosopher Prof Dr David Dusenbury. Luttwak tweeted on 30 June 2023:

‘There is no sign that the Ukraine war will end this year, or this decade. Do not believe the Ukraine counter-offensive will reach Mariupol to cut off all Russian forces further west, nor that Russians will descend from Belarus to cut off Kiev from Western supplies. Diplomacy anyone?’

Such realistic considerations are compatible with principled moral support for Ukraine’s defensive war against the Kremlin’s military aggression. Here I should cite the remarks made during the festival’s opening session by Tusványos’ main organiser, Zsolt Németh, who heads the Hungarian Parliament’s foreign policy commission. Németh argued that it is vital to keep reminding people that the Russian leadership is the aggressor in the conflict and that Hungary and other EU member states stand with Ukraine on matters of justice and sovereignty.

The Forest

With such heavy discussion topics, it was fortunate that Tusnádfürdő’s spas and strollable forests offer relaxation. One catch, though: the evening music was so loud that it drummed through the spa hotels and onto the valley’s forested slopes. A fine-souled author and avid enthusiast of the works of Estonian composer Avro Pärt texted me from his hotel room, indicating that the music playing downhill was not entirely congruent with his tastes. ‘THIS [expletive] LOUD MUSIC MAKES ME WANT TO STAB MY EARDRUMS SO I CAN SLEEP!’ I imagine the bears in the forest agreed.

Apropos bears: all the talk of them had made me curious. There was supposedly one behind every tree; many festivalgoers I spoke to, including Melissa O’Sullivan, had seen one or two the previous year. So, one evening, around dusk, I snuck into the forest by myself for about an hour, hoping to spot a bear (from a distance). Entering the woods, I walked past a red sign in Romanian with ‘urs’ on it. I am not particularly brave, but I make up for that with sheer stupidity. Three sane persons had independently of each other warned me about the bears, which had a ‘don’t-touch-that-button’-ish effect on me. But what truly did me in was the YouTube compilation ‘Cat vs. Bear Top 5,’ which features the five best videos of house cats chasing away brown bears. It installed the prejudice in my brain that brown bears are secretly softies. Only later, upon re-googling, did I stumble upon various ‘Bear chases skier’-videos set in Romania. Well, luckily, I did not encounter any bears in that forest. I did meet a giant snail, though. I quickly began filming it with my phone, only realizing three seconds in that my video would not be eventful.

Orbán on Bipolarity

Events unfolded on Saturday, however, the festival’s final day, when the Big Bear breached the camp’s perimeters. Viktor Orbán, Hungary’s prime minister, came to give his annual Tusványos speech. His Tusványos speeches are top-notch works of oratory. I recommend the English translations on the government’s website. As someone who occasionally reads speeches by American, Dutch, and Chinese politicians, which are heaps of mindless slogans and bureaucracy speak, I am amazed that Orbán’s speeches actually communicate ideas and give you things to think about.

This year’s speech reflected on the challenges of a rising duo-polar, Sino-American world. Orbán warns that China and the US will clash unless they change course. He observes that the political world is in a dangerous situation because the current number one power, the US, sees itself sliding back into second place and may react defensively and irresponsibly. Meanwhile, America’s appeals to universal values do not impress the Chinese,

who enter the world stage with a civilisational ego of cosmic proportions.

However, their reservations against American universalism are partly justified, Orbán suggests:

‘Asia, or China, stands before us fully attired as a great power. It has a civilisational credo: it is the centre of the universe, and this releases inner energy, pride, self-esteem and ambition…And it can neutralise the chief US weapon, the chief US weapon of power, which we call ‘universal values.’ The Chinese simply laugh at this, describing it as a Western myth, and noting that such talk of universal values is in fact a philosophy hostile to other, non-Western, civilisations. And, seen from over there, that view contains some truth.’

The solution Orbán proposes is for the great powers to leave room for each other. War can be avoided if the great powers rise above themselves, abandon a power-maximising approach, and recognise each other as equals. Humanity, and American and Chinese politicos in particular, should face up to the fact that ‘there are two suns in the sky’.

‘All we can say is that now something should be done that has never been done before: the big boys should accept that there are two suns in the sky. This mentality is radically different from the one we have lived with for the last few hundred years. Regardless of the current balance of power, the opposing sides should recognise each other as equals.’

Foreign journalists reporting on Tusványos usually focus solely on Orbán’s speech. Or, more precisely: on one or two phrases from the speech that can serve as the object of their dull moralising. Sure, the quotes are powerful. Still, it would be better if journalists would reflect on and transmit the argumentative and ideational content. But, above all, the festival is more than Orbán’s speech; it is also pork meat rolled into cabbages, ugly t-shirts, muddy shoes, people being embarrassed that they forgot the name of an acquaintance, bear talk, silly Dracula jokes by flown-in intellectuals, and citizens exchanging ideas about regional and world politics.

More than one kingly address, Tusványos is six days of democratic community building.

Unless otherwise indicated, all photos are courtesy of the Tusványos Facebook page.