‘We have learnt—and we are keenly aware—of the need to beware those people who are not interested in the problems of the present and the lessons of the past, but who instead promise a distant future of perfection.’

– Wall of Victims Page, Budapest House of Terror

‘Have Fun Behind the Iron Curtain’

– Home Page, Budapest Retro Interactive Museum

After visiting two very different museums in the heart of Budapest, these equally different quotes stuck out to me the most. The former comes from a display describing the unspeakable evils of the fascist and communist occupations of Hungary. Driving the point home was a Soviet tank that looked as though it had driven right out of 1956 and a three-story wall filled with the faces of victims to the oppression the tank represented.

The latter comes from the homepage for a museum centred on the popular and material culture of Hungary’s communist past. Behind it, the page shows interactive exhibits of old newsrooms, police cars, and phone booths.

Both represent the impact of communism and the Hungarian people’s victory over it in different ways, though it took some time and thought to realise how these two opposing perspectives and moods came together to tell the story of modern Hungary.

I first visited the Budapest Retro Interactive Museum during my first week in Hungary. Having a soft spot for vintage Americana from the same period (roughly the last half of the 20th century), I was excited to see the Hungarian equivalent. On that note, the museum did not disappoint. It was filled to the brim with old televisions and computers, cars and motorcycles, and one living room and kitchen suite stylishly decorated in 70’s orange. In some ways, it created this sense of a cultural bond.

It presented vintage vignettes that, language difference aside, were not unknown to my American conception of the past. At the same time, there was a very uncanny feeling about it all, and I felt I could not enjoy it completely. There was a very palpable disconnect between the charmingly retro exhibits and the constant, if subdued reminders that all of this took place under the weight of communist rule and the spectre of the Soviet military. Indeed, the same room presenting sports memorabilia and video game consoles featured Kalashnikov rifles, ‘The Internationale’ playing, and a Soviet missile displayed, very fittingly, directly overhead. Though I had enjoyed myself there, I left feeling puzzled at this apparent paradox of Hungary’s history.

Several days later, I had the chance to visit the House of Terror. The tone the museum conveyed could not be further from that of Budapest Retro. Monitors showed footage of German and later Soviet troops marching through the war-torn streets of the capital. Rooms filled with old uniforms and overstated propaganda posters and paintings left one with a sense of dread at the totality of the occupiers’ stranglehold on Hungarian society. The basement was the worst of all. It had been reconfigured into the hellish cellblocks and torture rooms that the oppressors deployed to enforce their iron grip over any who breathed the slightest trace of dissension.

The building itself bore the scars of this oppression, having been the very headquarters of the secret police that had enforced this unspeakable misery.

The experience left my heart bleeding for the tragedy that had befallen the people on that victim wall and those who survived them.

I was completely lost for words.

In fairness, the comparison between these two museums is not perfect, as the time periods they represent are not entirely the same. The House of Terror focuses largely on the fascist Arrow Cross and Nazi rule throughout the WWII period and the Soviet occupation and communist rule from the late 1940’s until the Revolution of 1956. Meanwhile, Budapest Retro focuses more on later decades between the 1960’s and the end of communism in 1989.

That being said, several exhibits in the Retro Museum date back to before the Revolution of ’56 and the last section of the House of Terror shows the final Soviet withdrawal from Hungary that only ended in 1991. In any case, both museums deal explicitly with the impact of communism on Hungary. Indeed, one room of the House of Terror shows everyday objects and advertisements in much the same way that Budapest Retro does, but rather than conjuring nostalgia, it highlights the underlying misery and hypocrisy of communist utopianism.

Even then, I was unable to piece together these radically disparate perspectives of Hungary’s communist past. Only on returning to Budapest Retro some days later with a friend who had just arrived in Hungary did I finally synthesise them. On my second visit, I noticed several things that I had not seen on my first. I heard political jokes poking fun at the ridiculousness of communism in one of the old phone booth exhibits.

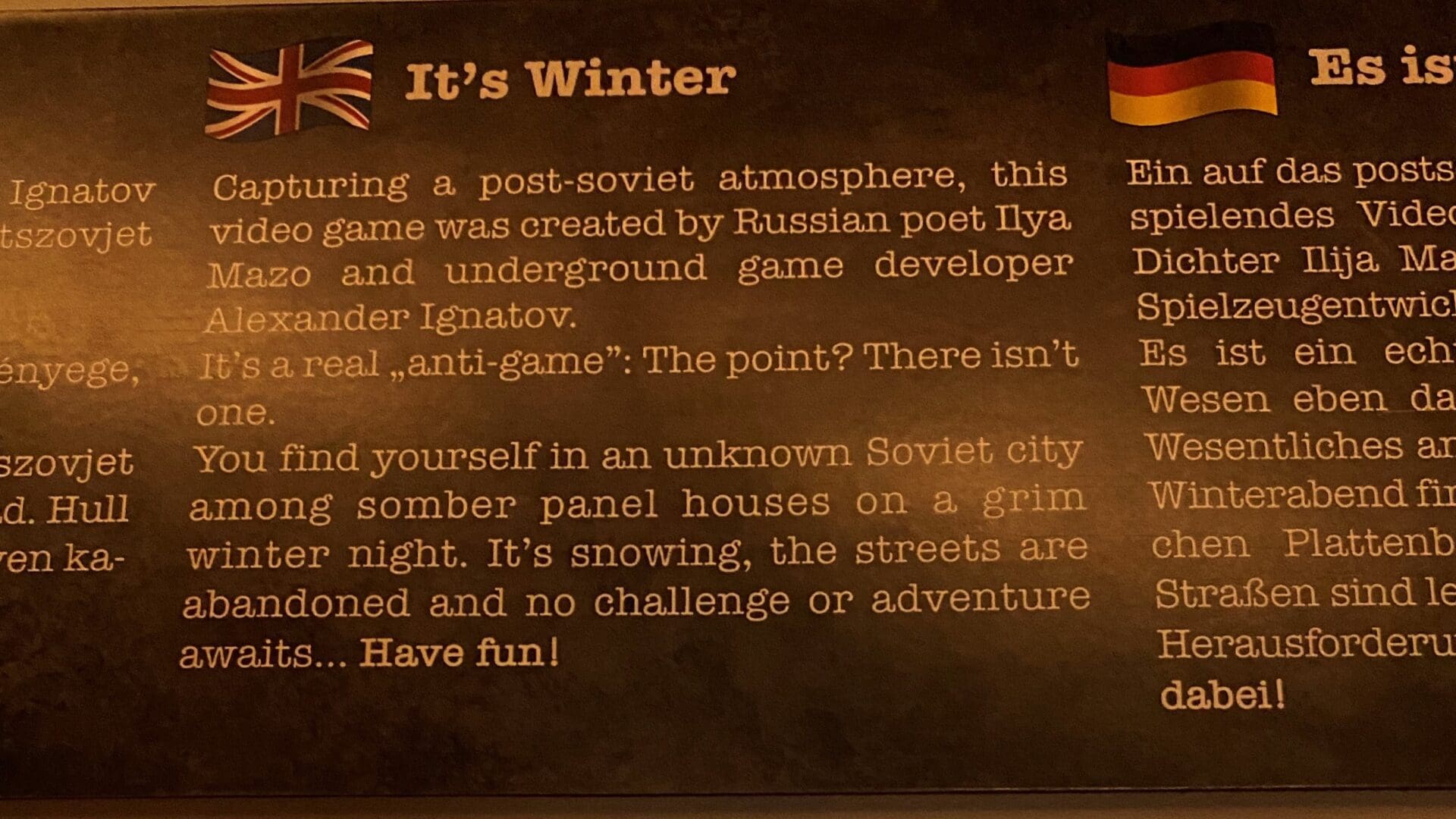

I read several news headlines highlighting the release of new cars or new phone lines that would be available in only a few short years (which I don’t doubt was normal under communism). I even played an amusing ‘anti-game’ set in a dismal communist apartment bloc in the bitter winter. The plaque for the game assured me that the game was completely pointless, that ‘no challenge or adventure awaits’ the game’s forlorn character. Nonetheless, the inscription ended with a sly exhortation to ‘Have Fun!’

That’s when it clicked. Much like those political jokes, the museum demonstrates the triumph over communism through humour and satire. Far from making light of the oppressive regime or downplaying its existence, it derides it in displays that paint it as a farce when compared to the true freedom and prosperity Hungary has experienced since communism’s demise.

At the same time, it cleverly reclaims the vibrancy of Hungarian popular and material culture in the last half-century in showing how it thrived even in spite of grim political circumstances.

In this roundabout way, it speaks to the everyday resilience of the Hungarian people that brought them through to the present.

To be certain, it doesn’t bear the same reverence and solemnity of the House of Terror, but it doesn’t try to. Where the latter paints a grim picture of tragedy under communist oppression, the former demonstrates levity in the face of such oppression that allowed people to endure. Most of all, Budapest Retro represents the humour afforded to us in hindsight, since we know that communism was eventually defeated. In other words, where the House of Terror makes one reflect on all that happened under communism, Budapest Retro bids one to smile because this tragedy is finally over.