This article was published in Vol. 3 No. 2 of the print edition.

René Descartes postulated that the sole attribute of res extensa, or ‘corporeal substances’ was extension. This Cartesian premise can usefully be applied to the modern state created by man, whether in the form of an empire or a nation-state: both are inseparable from this attribute. Even a uniquely ‘spiritual’ state such as the Vatican possesses physical boundaries, despite its tiny extent. Indeed, the essence of the modern state consists in its territory. Just as the members of the animal world are ruled by territorial instincts, the modern state has its own territorial nervous system and temperament. It is therefore strictly within a well-defined segment of space that each state has sway to enforce its sovereignty, political supremacy, and legitimate claim to use coercion. It is this territory it must defend, or even expand, as the case may be.

‘Man is a territorial animal in many senses, and he must inhabit continental physical geography’, writes Colin S. Gray, adding that no conflict is conceivable beyond the limits of that space.1 The modern relationship between territory, sovereignty, and political entity has been addressed from many angles in a large corpus of theoretical literature. Consequently, what follows is but the sketch of a draft touching on the issue.

Realities and Utopias

The religious and even mystical concept of space of the Middle Ages was toppled by the great geographical discoveries, the colonization of an Earth recently recognized as spherical in shape, and the emerging system of international law founded on nation-states (ius publicum europaeum). In the process, former geographical explanations were superseded by the map—a representation of space that now not only indicated but asserted units of sovereignty by depicting their boundaries. Ostensibly a neutral image, the map became suffused with political meaning expressed by states aware of their own space, rendering sovereignty visible, as it were. This is how we gained our complex ‘knowledge of space’.2 The organic correlation between sovereignty and territory has been universally recognized since the Peace of Westphalia of 1648, which ended the Thirty Years’ War. Since then, international politics has been synonymous with political relations among states with a defined territory.

Carl Schmitt, one of the iconic figures of conservative political thought, deems this correlation immutable. As politics is ab ovo inseparably intertwined with the territorial idea, he argues that associations of friendship and enmity at the core of politics invariably arise in a definite physical space, and therefore the territorial aspect can never be banished from the sphere of political considerations. As for the evolution of the concept, Schmitt emphasizes that, in the modern era, the Anglo- Saxon countries, having come into ascendancy as a result of colonization, have been quite adamant about supporting the causes of free world trade and minority rights, despite the fact that neither liberal individualism nor the doctrine of supranational universalism are remotely capable of serving as the cornerstone of international law. In reality, free trade and the universal proclamation of private property only constitute a screen for concealing the Anglo-Saxon hegemony founded on sway over the seas of the world.3

As an aside, let us remember that the earth and its waters have always been central to the material aspects of geopolitical thought, even if the relationship between these two elements has been contemplated in disjunctive terms, giving precedence to one over the other as the essential medium of power. According to Raymond Aron, the choice between the two comes down, beside the specifics of geography, to deeper underlying considerations, particularly in the case of countries that are theoretically free to deliberate between the two alternatives:

‘There is every reason to regard as fundamental, throughout history, the opposition of land and sea, of continental power and seafaring power. The two elements seem to symbolize two ways of life for men, incite in them two typical attitudes. The land belongs to someone, to the landlord, individual or collective; the sea belongs to all because it belongs to no one. The empire of continental powers is inspired by the spirit of possession; the empire of maritime powers is inspired by the spirit of commerce. [L]and and water represent the two elements in conflict on the global stage […].’4

While Aron’s train of thought is not without appeal, it is far from certain that the urge to possess is an attribute of mainland powers alone. Here, Aron (a liberal Frenchman) does not see eye to eye with Schmitt (a conservative German) for reasons it would require too much space to discuss. Suffice it to recall that the United States, before becoming a maritime power, had to gain possession of the northern half of the Americas, to the detriment of the American Indian population. It was only after this genocidal territorial campaign had been successfully completed that the United States, now with the entire mainland in its pocket, got a whiff of the airs blowing over the oceans flanking it.

Commercial and economic considerations asserted themselves early on in the colonial period. Indeed, they were the essential driving force behind the military conquests. The gobbling up of one territory after another was immediately followed by the expansion of trade companies, which would acquire even greater influence later. Nowadays, neoliberal, global capitalism seeks to deprive the political domain of its existentially fundamental territorial nature, in an effort to sacrifice sovereignty on the altar of supranational economic unity. What the global economic interests have had in mind as the vehicle of political action are not individual nation-states but an economic space stretching over state boundaries. Their final, utopian goal is a global state representing some kind of universal order, a new structure and logic of management. They extoll this dream as the ultimate form of sovereignty, which will negate the need for any balance of powers.

‘Nowadays, neoliberal, global capitalism seeks to deprive the political domain of its existentially fundamental territorial nature, in an effort to sacrifice sovereignty on the altar of supranational economic unity’

The same future is visualized, but with reproach, by the (neo)liberal thinkers Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri. They consider that the logic of global capitalism is leading to a faceless world ruled by a kind of imperial order, which is dissolving traditional communities in a shapeless mass and subordinating the entire planet to a single authority. It is institutionalizing a standardized global market with its own political and legal sovereignty, which allows at best a semblance of national sovereignties to survive for show. Ultimately, this new empire executes a ‘revolution of space’ that blurs former lines of physical demarcation and creates a ‘level playing field’ wherein everything can flow freely and without impediment. Impossible to localize, the Empire is omnipresent. Its very nature therefore is virtual, delocalized, and decentralized, in stark contrast to that of nation-states, which centralize force within precisely defined national boundaries and are vested with a public power that is very real rather than virtual. In other words:

‘[…] we have witnessed an irresistible and irreversible globalization of economic and cultural exchanges. Along with the global market and global circuits of production has emerged a global order, a new logic and structure of rule—in short, a new form of sovereignty. Empire is the political subject that effectively regulates these global exchanges, the sovereign power that governs the world.’5

Carl Schmitt, recognizing these perilous tendencies in their embryonic stage, made an early distinction between empire and ‘great space’ (Grossraum), arguing in favour of the latter as the ideal component of an arrangement of discreet major powers. For Schmitt, the world can only be rational if it maintains an equilibrium among several, mutually independent and internally homogeneous great spaces, each preserving its own status as a nation-state. The great spaces, says Schmitt, form a security zone and a belt of radiated influence which all peer powers must acknowledge.6 In the absence of such a balance, international relations will look like what Robert Gilpin describes as ‘a jungle out there’.7

The rule of an all-encompassing government of the empire that stands for ‘global sovereignty’ may not yet be quite imminent, but it is nevertheless true that global capitalism has been constructing an abstract worldwide space through its networks, modelled after the movements of capital within and among individual nation- states. The power nodes of the new world map, particularly the truly decisive centres of production, are defined by the points where the networks of commerce, information, and transport interleave and intersect.8 This logic perceives geographical space itself as part of a process of production and consumption, using it as a point of reference in classifying the simultaneously concrete and symbolic territories of nations by functionally overwriting and reinterpreting them.9 Indeed, the mainstream neoliberal ideology of globalization attributes advantages only to the drive for standardization that characterizes global capital—another new utopia, to be sure. Its proponents argue that its effects will tame, and eventually even eliminate, traditional power conflicts by diminishing the millennia-old overriding significance of politics. In the process, the nation-states will be reduced in their functionality, becoming of secondary importance as entities, and the principle of territorial existence will slowly dissolve into a new, boundless uniformity. To use a rather un-English term, we are going to witness the deterritorialization of the world—a world deprived of the territories of its constituents, at least if we are to believe the new utopians. Richard O’Brien goes so far as to talk about the ‘death of geography’, suggesting that our conventional maps are being rendered useless by economic progress, and most notably by international financial manoeuvres.10

Let us assume for a moment that we are in the position of making out the death certificate of geography. But can we really ignore the ample experiential evidence of how structural inequalities are always reproduced, triggering new tensions? Let us not fall into that trap, as O’Brien does. In the vision of a brave new world of constant progress without geography, the old power clashes will be stubbornly reiterated, potentially spilling from one country or region to the next, inflating local skirmishes into regional, even global conflicts, which cannot be managed, let alone relieved or solved, by utopian ideas.

Meanwhile, the spaces of our Earth still habitable by humankind are shrinking rapidly, entailing consequences that remain unforeseeable but will certainly aggravate the prevailing chaos of international relations—just think of the mass exodus often simply called ‘migration’. Today, the ecological destabilization of our habitat could only be mitigated by ‘a dictatorship of planet engineering’, to quote Hungarian Ministerial Commissioner for Space Research Orsolya Ferencz, and it would be a mistake to regard the scenario of such an eco-autocracy emerging as a figment of the imagination entertained by someone behind a desk.

So should we really toss out our old, worthless maps? But why should the new ones be useful as trustworthy maps of world peace? These questions point to the depth of the fault lines between ways of interpreting a world constantly in flux. Such dilemmas have always been at the core of academic discourse, and quite naturally so. What ought to give us pause is the ongoing deepening of actual fault lines around the globe which could not care less about theoretical debate. No wonder then that the issues of space as we know it—including land, seas, oceans, airspaces, the arctics, and even airspace—have been attracting distinguished attention among social scientists. Besides the geoeconomic views seeing the international rivalry as grounded in economic networks,11 international literature is being pervaded by voices dispensing with any illusion regarding old-world realities of power. Robert Kaplan, for one, goes out on a limb by predicting nothing less than the ‘revenge of geography’. He argues that no progress, be it economic or technological in nature, can afford to ignore the principle of territory, because the sum of geographical factors inevitably impacts international processes, the approach of politicians being first and foremost among them, as has been eloquently shown by the events of recent years.12 In short, in a world where the failure of both old and new utopias (the scientific-communist project and, respectively, the equally technocratic if neoliberal dream of Silicon Valley) can be credibly presented as a half-success, why should we not deem geography incapable of settling scores? Why is it inconceivable that geography, dismissed by the utopians, could rise to centre stage once again? Whether we like it or not, the return of geography as a major element is set to become one of the prominent phenomena the twenty-first century will be remembered for.13

Yet the question implied in my title—is a revenge of geography in the wings?—must be answered in the negative. Far from it. Geography, as the immutable spatial foundation of organizing any society, will simply continue to exist, no matter what. It is not going to let itself be wiped out, even from the charts of academic discourse, and certainly not for the sake of the visions of progress entertained by utopian thinkers. How could this be revenge? No, it is just plain reality.

International Actors, Global Chances

For quite a while now, we have been beset by the perils of unbalance. It seems that paradise on earth, ‘the end of history’, has not been clinched by the triumph of global capitalism, despite the somewhat premature claims of Francis Fukuyama.14 For decades, we have been fumbling in the ‘fog of peace’ nourished by latent tension and unstable security.15 Now, we know that such nebulous times often end in war, a means of solving confused relations of power by means of violence.16 Ever since the bipolar world ceased to exist, the ever-present anarchy quotient of international politics has only been ratcheted up, and the absence of a world order will continue to engender more disorder until a new order, whether bi- or multipolar, emerges—if one ever does.

‘Nation-states will be reduced in their functionality, becoming of secondary importance as entities, and the principle of territorial existence will slowly dissolve into a new, boundless uniformity’

As another aside, let me interject that any world order is always unjust because it imposes uneven restrictions on nation-states. Make no mistake, this is just as true for the former bipolar structure. Yet we would be well-advised to remember that the only thing more dangerous than injustice is the absence of world order, when the ability of major powers to keep one another at bay breaks down. And herein consists the greatest challenge facing the twenty-first century, which is proving more chaotic than we thought—in the lack of world order. More than ever, it is now imperative to fashion a new, preferably less unjust, world order whose beneficiary (to be lofty about it) will be mankind as a whole, and its de facto subjects (less loftily) will be the extant major powers and, more generally, the nation-states. It is a matter of sheer survival for every nation whether it goes down the drain or manages to fit into a new global scheme, and perhaps even to shape it to fit its needs.

Without a doubt, the increasingly messy conditions of the present era will eventually spawn new power relations, although for now they have only succeeded in muddling the formerly stable international hierarchy. Some nations rise while others slip back in rank, and each actor constantly strives to maintain or improve its position, weighing the cost–benefit ratio of moving up on the ladder, trying to gauge the returns on investing in the adjustment of the prevailing international order (or disorder). Whichever way they decide, however, the looming issue is that of a newly redivided world, in which all players will spare no effort to achieve calculated advantages. Which of them will succeed and which will fail in this effort depends on what is called the cycle of relative capability of each nation. The term refers to the ability of a nation to change its position in the hierarchy. This cycle has a rising phase and a declining phase. In the former, the given nation can bank on returns from its investment of effort, and will stand a chance of ascending in international rank. In the latter, the nation will be subject to coercive circumstances, both internal and external, which will at best allow it to avoid backsliding, and most often not even that.

An American author precisely identifies the point in the impending redivision of the world where the threat of war becomes truly imminent among ‘revisionist (upcoming) powers’ and the United States, a country intent on preserving its status as a singular superpower.17 This assessment is not so much prophetic as it is plain realistic, as evidenced by the Russia–Ukraine War now under way.

But why Ukraine, of all places? As has been pointed out by many commentators, Ukraine—a symptomatic scene of the emerging new global division—has always been predestined by its geographical position, sheer size, economic potential, and its own dividedness along religious and cultural lines, to serve as a major theatre of various political ambitions. Suffice it to look back upon the reigns of Peter I, the Great (1682–1725), and Catherine II, the Great (1762–1796), when most of its territory came under the control of the Russian Empire. In the next century, it was considered the most industrially advanced province of tsarist Russia, even as it managed to hang on to its distinguished position as a potential leader in European agriculture. When the Empire collapsed in 1917, Ukraine declared itself an autonomous republic, which survived until 1920, when it was occupied by the Red Army. Two years later it became one of the founding member states of the Soviet Union as the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.

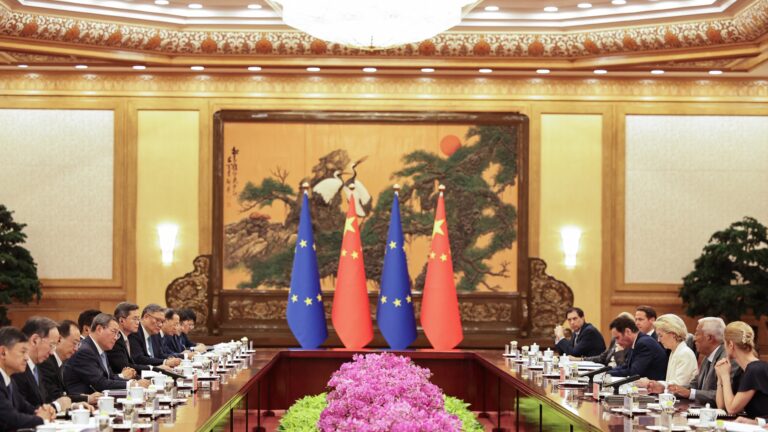

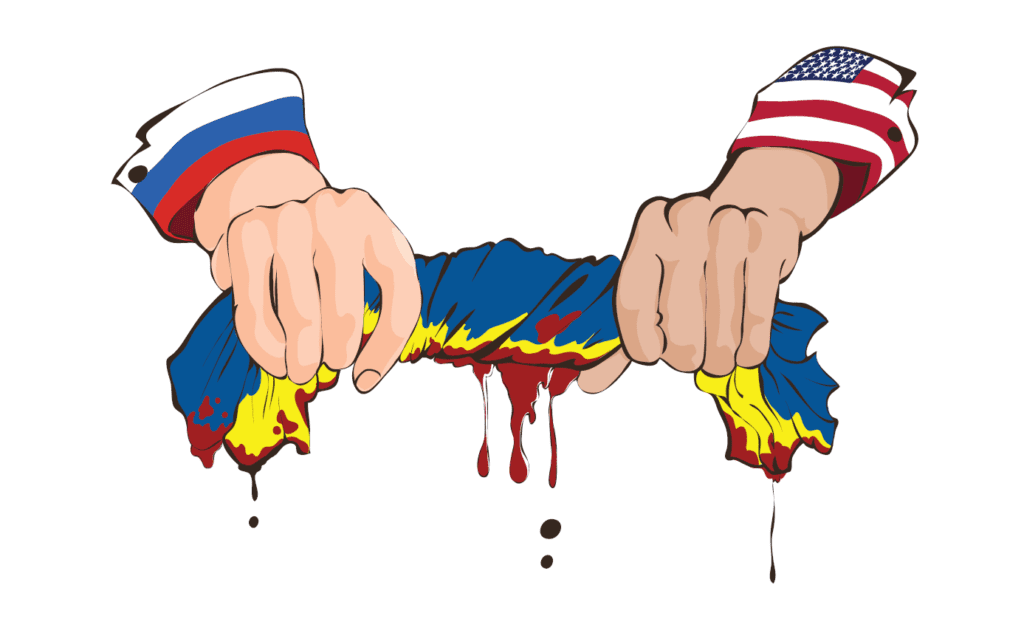

Ukraine’s political tribulations were put on hold during the Soviet era, given that as part of one of the two superpowers of the reigning bipolar world it counted as an unshakeable ingredient of the status quo instated by the Yalta Conference, whose political allegiance was never for a moment questioned. Then, the collapse of the Soviet Union instantly revived the tenacious geopolitical traditions concerning it as an entity in its own right. The United States (now alone as a superpower) and Russia (demoted to a major regional player but still a global threat owing to its massive nuclear arsenal) immediately embarked on a latent rivalry for control of Ukraine. The United States, in the name of a foreign policy driven by essentially rational value-based interests behind a smokescreen of vaunted moral values, entered the scene as a staunch supporter of Ukrainian freedom and democracy, while casting a beneficial veil over its genuine economic, military, and geopolitical interests, including those of arms manufacture. Russia is more straightforward about its motives. Its declared purpose is to preserve its own security buffer zone, citing the ‘organically’ shared ground between Russia and Ukraine’s recent past. Of course, neither party would qualify this conflict as a war in the traditional sense of the term. The United States will not because it is not committing troops either formally or physically, only weapons (or weapon systems, to be more precise). For its part, Russia has from the start described its escalating military campaign as a ‘special operation’.

But why this politico-linguistic coyness? Why not call the thing by its name? Well, Ukraine—the bloodied object of the rivalry—is alone permitted to call this war a war, if nothing else. Beyond the usual hypocrisy of communication bent on manipulating public opinion, the linguistic creativity of rivals must obviously be blamed on the fact that both have steered clear of a nuclear showdown, for the time being. They believe they would have a harder time doing just that if they explicitly recognized the conflict as a war, even as they continue to engage in mutual threats. ‘This is a chess game with death’, Dmitri Medvedev, the former prime minister and president of Russia recently averred.

This type of verbal beating around the bush is all the more symptomatic because the parties remain reticent about the meaning or purpose of the war itself. It is as if the war rattled on gratuitously, as it were l’art pour l’art. What could be more dangerous than that? And what realistic objectives can we surmise behind it?

‘America has a vested interest in maintaining geopolitical schisms (or, to use its ideologically equivalent term, pluralism) in Eurasia’

Russia claims that it will end this ‘special operation’ when it has accomplished its goal, except that that goal remains ill-defined and unclear. As a flat country providing troops with easy access to Russia’s heartland, Ukraine has been at the crux of Russian geopolitical fears for a long time. Throughout its history, it has served as the conduit of several attacks from the West, traversed by Polish, Swedish, French, and German forces. In that sense, Russia’s concerns are understandable, particularly if the proximity of NATO is now taken into account. But there is no way Russia can possibly occupy all of Ukraine. To date, it has managed to annex but one fifth of the country’s territory. This speaks to the obscurity of Russia’s military objectives, without even addressing the uncertainty of any political denouement further down the line. Which territories would quench the thirst of Russia? And would Russia be satisfied with limited territorial gains to begin with? What kind of guarantees and political schemes in Ukraine would satiate Russia?

On the other side, the moral rhetoric of the United States glosses over the fact that Ukraine is a key country for American global strategy. According to an old, tenacious American doctrine, the economic and political counterweight of the United States’ global supremacy is located in Eurasia. The prevailing division of power in this large portion of the Earth’s surface remains of crucial consequence for America. Specifically, America has a vested interest in maintaining geopolitical schisms (or, to use its ideologically equivalent term, pluralism) in Eurasia. This is the token of preventing any single state, or a coalition of states, from posing a threat to American global pre-eminence. The only alternative to that, in the eyes of Washington, would be international anarchy, from which nobody would benefit. America deems a Russia without Ukraine to be incapable of becoming a protagonist of any Eurasian alliance with superpower ambitions—a role also coveted by China. It is another matter that, by weakening Russia, the United States might inadvertently improve China’s manoeuvring options, blind to the fact that a courtship between Russia and China, with Beijing taking most of the credit for the romance, could be even more perilous to American interests.

Last but not least, the Ukraine War is also proving useful as the chimera of Russian threat which the United States can repeatedly raise as a pretext for ratcheting up its sway over Europe. In energy affairs it has already achieved stellar success in this effort, but it will not stop there in the pursuit of its ultimate goal, the conclusive integration of Europe, and more narrowly the European Union, within a global system under American dominance, in economic, military, and political terms. Joe Biden has been quite upfront about this agenda, saying that the United States now has an opportunity that only occurs in three or four generations. ‘There’s going to be a new world order out there’, the President continued, ‘and we’ve got to lead it. And we’ve got to unite the rest of the free world in doing it.’ As for the semi-legitimate hints that America may ultimately be after the overthrow of Putin, possibly even the collapse of Russia, that is no more than wishful thinking that only attests to a total misunderstanding of what the Russian mentality is about.

Geopolitical Chess

The for now unknown outcome of covert geopolitical games around Ukraine will hinge upon the ability of the two leading actors, the United States and Russia, to size up their chances realistically. The same holds true for China, another major player, though involved only indirectly in the conflict. Much will depend on the specific phase of the cycle of relative capability each actor happens to be in, and on whether they entertain illusions about their limits. Seen from this angle, the shifts performed by them trace markedly different curves.

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union and its sphere of influence, the United States found itself in the position of sole superpower, at the apex of its cycle of relative capability. With the implosion of its ideological arch-enemy in 1991, it seemed that the bipolar world order would be followed by a unipolar order spearheaded by the United States, and everyone would have no choice but to toe the line of American power logic. This assumption reached its pinnacle of strength in the 1990s, during the Yugoslav Wars. Never since then has the United States come so close to winning international consensus in recognizing its global supremacy. However, this quasi-unipolar world order was shaken by the terrorist attacks of 9/11, 2001, and then the Great Recession, the global economic and financial crisis of 2008 put a peremptory end to the hopes of what Charles Krauthammer had called the ‘unipolar moment’. From that point on, it became clear that Russia, China, and the upcoming regional powers were not at all interested in the consolidation of America’s global power, but rather in the emergence of a multipolar world serving their own goals. Since the first decade of the twenty-first century, the world has obviously existed in a limbo state between ‘no longer’ and ‘not yet’, though it is equally undeniable that America has continued to reign supreme over this chaos. The United States remains the most powerful state-based empire, with enough clout and force at its disposal to thwart, for the time being, the formation of a multipolar order, or a new bipolar order, this time organized around America and China—both scenarios being utterly undesirable for the United States.

All things considered, the cycle of relative capability of the United States has displayed a downward trend in recent years, even if in absolute terms it remains higher than those of the others. At the same time, much of ‘the rest of the World’ (meaning all the non-English speaking countries) has harboured markedly anti-American sentiments that may in the future not only gather strength but become more tightly institutionalized, as has been illustrated by several recent developments. That the current war is set to accelerate both trends is exemplified by the increasingly well- negotiated, cooperative approach between Russia and China.

Russia’s cycle graph is far more jagged. The country’s leverage and ability to enforce its interests plummeted to a nadir with the unravelling of the Soviet Union associated with Mikhail Gorbachev. In the 1990s, not only did Russia suffer severe territorial losses, it also saw its economic prowess wane, both setbacks causing a trauma that proved difficult to process for both the state and the psyche of the Russian people. Under the presidency of Boris Yeltsin, whose policies were rather agreeable for America, the situation slowly became untenable. Now Russia had to deal with the mounting risk of having its economy, and particularly its internationally significant stock of resources and energy, fall under decisive American influence. Then Vladimir Putin emerged on the stage, bringing change. In 1993, still under Yeltsin, the government had declared what became known as the ‘Russian Monroe Principle’, asserting its notional claim to the ‘near-abroad’ areas within the narrower perimeter of the former Soviet Union (as opposed to the entire former Soviet empire), and demanding that the world recognize and respect it as a vital periphery of Russian interests. This seemed no more than a rhetorical exercise at the time, in part because Russia lacked the resources to implement and enforce the principle, and in part because its zapadnik rapport with the West (i.e., one based on the recognition of a shared destiny) had not yet deteriorated. In those days, Russia still sidelined the bitter assessment of Nikolay Danilevsky, who says that the West does not know Russia, because it does not want to know it. Better put, the West knows Russia as it wants it to be known, to conform to the disdain lavished on it.18

Putin set about restoring Russia’s self-image, sneaking Russian pride in through the back door, as it were. He rekindled the sentiment of derzhavnost, the sense of belonging to a major power, understood as an entity that is powerful but less than an empire—most akin to Schmitt’s previously mentioned notion of a ‘great space’. As long as energy prices allow, Putin will be able to stockpile massive financial resources to finance his pet project of resuscitating this great space, and will happily abandon the age-old but never-accomplished Russian (Soviet) ambition to become an industrial superpower capable of competing with the West. Instead, he is building his economic strategy on a pointedly national exploitation and export of natural resources. He never for a moment forgets that much of Europe depends heavily on crude and gas deliveries from Russia, and he remains ready to forge a potentially enduring energy partnership with Germany, the most powerful state in Europe. Nor is he being discouraged in these hopes, for there are evident signs of such willingness on the other side. In the process, he is setting off the usual alarms in Washington which has always eyed with suspicion any strategic dependence excluding the United States. (Let us remember the coincidence with the Echelon scandal, with Germany resenting its own surveillance by the United States, one of its allies.)

Sensing the renewed hostility of America’s Russia policy, Putin has left no stone unturned in his efforts to repair relations with territories that have spun out of the orbit of the Soviet empire. By harping on the rhetoric of the ‘near-abroad’, he expects the world at large to understand and respect Russia’s traditional geopolitical objective, which consists of forming buffer zones to the West, controlling seaports in the South, and ensuring a depth of strategic defence in the Russian mainland to the East. Going beyond these ambitions at the Munich Security Conference in 2007, the Russian president signalled his resistance to the new quasi-unipolar world order, and has been warning that NATO’s eastward expansion (an undeniable fact) to the detriment of Russia (who else?) may force Russia to adopt firm measures in response. His ability to assign not just words but resources to his ‘near-abroad’ concept is nowhere more apparent than in the 2008 Russo–Georgian War and in the annexation of Crimea in 2014. Moreover, in the Syrian conflict he went so far as to demonstrate Russia’s ability to stay the course with America, if in specific respects only. Now, the demonstration of force is all-important as one of the major tokens—perhaps the only one—of what global leverage Russia still hangs on to. It is imperative for Putin that Washington recognize Moscow as a major military power of the world, second in quality and striking force only to the United States.

At the same time, the ballooning ambitions of Russia seem overly optimistic in light of the conspicuous ailments of its economy. To this date, the country has not answered the nagging question of how far its stockpile of natural resources and energy can be stretched in the absence of a modernized economy that would ensure a deeper, more diversified footing. As the liabilities of maintaining its military can easily be stressed by the unstable economic structure, Russia can hardly entertain hopes of a global leadership role. We also know that the demise of the Soviet Union was to a large extent due to its lack of a sense of proportion. In terms of GDP, Russia today is comparable to the economy of Spain, and that is hardly sufficient for more than the active management of its ‘near-abroad’ relations. Even more to the point, its backwardness in terms of technology and innovation has deepened the gulf between Russia and its global competitors. Russia would therefore be well advised to take to heart the observation of Mikhail Delyagin, one of the few clear-thinking geopoliticians in Russia these days, when he says that thank God, Russia can no longer hope to conquer the world. But this gives us another task, no less difficult though possible to accomplish: that of convincing the world of this fact.

For all these symptoms, the weaknesses and passivity that characterized Russian foreign policy in the 1990s are now things of the past. Since the turn of the millennium, Russia has been muscling up, having found new boldness in pursuing its ambitions, and its cycle of capability is in the upswing, even if its curve has been producing rather sharp peaks and valleys over the past three decades. The Ukraine War is likely to impose on the country an economic downturn for the longer term, leaving Russia to seek a way out of its predicament not so much by reaching out to the West as to a China which has been working diligently on establishing its superpower standing—with the different but hardly minor pitfalls such an enterprise entails.

As for China, the bipolar world order after 1945 ought to be regarded in hindsight as a power scheme of 2+1, even if China itself at the time described itself as an aloof beast perched on a summit, looking down upon the fight between the two supertigers in the valley deep below. The metaphor was certainly apt: China was not yet a supertiger, but occupied a mountain peak above them. It was not as strong as the two apex predators, but kept an eye on them from on high, scrutinizing their strengths and weaknesses. It was therefore not so much outside the rivalry as above it, in a position where it could afford not to take notice of the struggle if it so pleased or, to be more precise, if this were dictated by its interests. However, in the twenty-first century, China’s policy has been anything but aloof and uninvolved.

At the dawn of the modern era, the Chinese still had reason to believe that the Great Wall was eternal and could be maintained to the end of time, regardless of the circumstances. Then their bitter experiences in the nineteenth century, notably the Opium Wars (1832–1842 and 1856–1860), made them realize that this was not the case. Once they had established ties with the modern world, insisting on remaining closed to it would only lead to fiascos and unresolvable tensions. They could no longer hang on to the complacent premise that had, for centuries, even for thousands of years, proclaimed China to be the half of the world (the Middle Empire under the Skies) that really mattered, while the rest of humanity was living in barbaric states somewhere on the periphery. If there was a ranking to be set up among them, the sole yardstick would be how closely each approximated China’s unrivalled perfection. This static view was first challenged in the Middle Ages by the Mongolian influence, under which the empire became more expansive, although the Confucian philosophy of aloofness survived in the deeper strata of Chinese society and thought. Why bother conquering the outlying lands of barbarians? In the first half of the fifteenth century, Zheng He (Cheng-ho), a Chinese admiral of Mongolian extraction, led seven maritime expeditions to the shores of the Indian Ocean, marking the first and last attempt to build China into an empire. The admiral’s achievements proved more useful as a show of strength than as a means of acquiring actual colonies. China never entered the maritime race for global supremacy in early modern times, for reasons that remain inscrutable to this day. Later, in the modern era proper, the supercilious policy of aloofness was augmented by the reluctantly undertaken task of ‘self-strengthening’ under pressure from the aforementioned traumatic conflicts with the West. China decided it had no choice but to learn whatever it could from the Western barbarians, especially their technical advancement, but without compromising the fundamental values of traditional Chinese society.

‘It is imperative for Putin that Washington recognize Moscow as a major military power of the world, second in quality and striking force only to the United States’

This process of ‘self-strengthening’ gathered speed in the twenty-first century. Following Mao Zedong’s experiment with Chinese-type communism, Deng Xiaoping discarded the communist utopia, choosing instead to rely once again on the tradition of meticulous precision, patience, and concentrated attention that had characterized the Chinese habit of mind for millennia. From among the conflicting alternatives of organizing society, he prioritized those promising to be useful for China: from capitalism, he borrowed the relentless rule of performance; from communism, the individual’s subjection to collective interests dictated from above. No matter how you look at it, it was on the basis of this policy and the Tiananmen Square Massacre of June 1989 that a special Chinese form of communist capitalism sprouted, giving the lie to all the wisdoms of transitology by proving successful, in its own way, in putting into practice a convergence of diametrically opposed principles of social organization. At the end of the day, no one has managed to come up with a theoretical explanation of what is happening in China, or to even get remotely close to deciphering the secret. In any case, everyone must acknowledge the practical achievements China has to show for itself.

Some of it must have to do with the philosophy of leisurely action, so different from the Western perception of time, with soft expansion, and stealthy influence—all of which continue to define the geopolitical attitude of a China that has been gaining spectacular strength since the turn of the century. The country already leads the world in several indices (for instance in GDP expressed in purchasing power parity) or at least comes a close second behind the United States. It keeps abreast of technological development, by copying others if it finds no other way. For now—and let us emphasize for now—it only falls behind its rivals, including Russia, in terms of military striking force. Having said that, we should have no doubt that the multiplying data regarding Chinese armament are being watched keenly and with mounting unease by its rivals. Of special concern is China’s development of a ‘blue-water navy’, meaning an arsenal of vessels capable of not just near-shore but open-water warfare—eloquent proof that mainland China intends to become a maritime superpower sooner or later.

To cut a long story short, the curve of China’s cycle of relative capability is rising steadily, in contrast to the sloping trend of the United States and the zigzag of the Russian graph. China can keep track of the Ukraine War from a geographical distance but without denying or dismissing its involvement in the global game and tailoring its attitude to its own interests, and this could be particularly worrisome for the United States. As for Russia, if it wants to be realistic about it, it cannot afford to let its guard down even if its interests happen for the time being to coincide with those of China.

What About Europe?

Unfortunately, this section of my essay can be dealt with briefly. Europe’s cycle of relative capability—if one can be drawn up at all for such a diverse entity—has been ailing for decades, without displaying any sign of improvement in the wings. The foreseeable future will be decided by the conflicting geopolitical ambitions of the three major powers, each in a different phase of its cycle of relative capability. It will be a clash between global, imperial, and macroregional intelligences, between arsenals of knowledge and capabilities mainly brought to the fray by America, Russia, and China, without of course discounting the other actors. For us Hungarians, the cardinal geopolitical question of the twenty-first century is and will be whether Europe can alter the trajectory it has followed for a long time, perhaps not so much as a matter of sheer destiny as owing to its own ill-advised decisions and behaviour. A new utopia would hardly point the way out. In any case, the Russian–Ukrainian conflict, which is the most massive war on the continent since 1945, will not do much to improve our chances, to put it mildly.

Translated by Péter Balikó Lengyel.

NOTES

1 Colin S. Gray, ‘The Continued Primacy of Geography’, Orbis, 2 (1996), 247–276.

2 Yi-Fu Tuan, Space and Place. The Perspective of Experience (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001).

3 Carl Schmitt, Land and Sea [1942], trans. Samuel Garrett Zeitlin (Candor: Telos Press, 2015).

4 Raymond Aron, Peace and War (London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 1966).

5 Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Empire (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001), xi.

6 Carl Schmitt, The Nomos of the Earth in the International Law of the Jus Publicum Europaeum [1950], trans. G. L. Ulman (Candor: Telos Press, 2006), 41.

7 Robert Gilpin, ‘The Richness of the Tradition of Political Realism’, International Organization, 38 (1984), 290.

8 For details, see Zoltán Cséfalvay, A nagy korszakváltás (The Great Paradigm Shift) (Budapest: Kairosz, 2017).

9 Cf. Norbert Csizmadia, Geofúzió. Miért fontos a földrajz a 21. század gazdasági és geopolitikai világában? (Geofusion: Why Geography Matters in the Economic and Geopolitical World of the Twenty-first Century) (Budapest: Pallas Athéné, 2021), and Geopillanat. A 21. század megismerésének térképe (Geoseconds: A Map for Discovering the Twenty-first Century) (Budapest: L’Harmattan, 2016).

10 Richard O’Brien, Global Financial Integration. The End of Geography (New York: Council on Foreign Relations, 1992).

11 Cf., for instance, Paul Krugman’s relevant works, including End This Depression Now! (New York: W. W. Norton, 2012); The Conscience of a Liberal (New York: W. W. Norton, 2007); The Great Unraveling (New York: W. W. Norton, 2003); and Parag Khanna, Connectography: Mapping the Future of Global Civilization (New York: Random House, 2016).

12 Robert D. Kaplan, The Revenge of Geography. What the Map Tells Us about Coming Conflicts and the Battle against Fate (New York: Random House, 2013).

13 Tim Marshall, Prisoners of Geography. Ten Maps That Tell You Everything You Need to Know about Global Politics (London: Elliott and Thompson, 2015).

14 Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man (New York: Free Press, 1992).

15 Emily Goldman, Power in Uncertain Times. Strategy in the Fog of Peace (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2011).

16 Geoffrey Blainey, The Causes of War (New York: Free Press, 1973).

17 Jakub J. Grygiel and A. W. Mitchell, The Unquiet Frontier. Rising Rivals, Vulnerable Allies, and Crisis of American Power (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016), 11.

18 Nyikolaj Danyilevszkij, ‘Oroszország és Európa’ [1871], in Oroszország és Európa. Orosz geopolitikai szöveggyűjtemény (Russia and Europe. Collection of Russian Geopolitical Texts), ed. Ferenc Gazdag (Budapest: Zrínyi, 2004), 71–144.

Related articles: