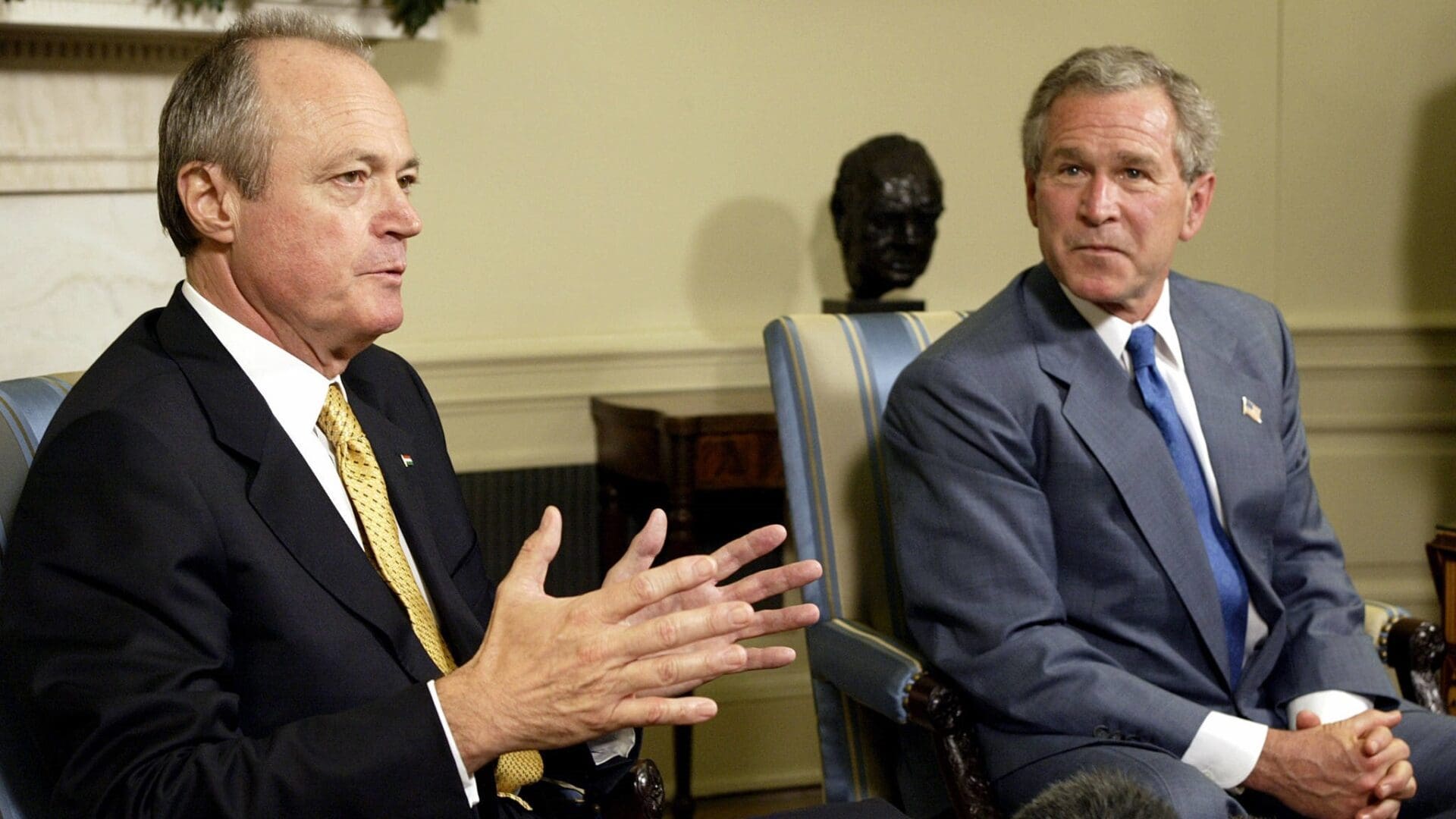

Péter Medgyessy is a former Socialist politician and businessman who served as the prime minister of Hungary between 27 May 2002 and 29 September 2004. He announced his resignation on 19 August, and resigned on 25 August 2004. He remained in office as the acting head of government until late September, when his successor, Ferenc Gyurcsány, was elected by the Hungarian Parliament.

Medgyessy succeeded Viktor Orbán as prime minister in 2002. He was no newcomer to politics; he had served in high-ranking political positions in Hungary even before the fall of the Berlin Wall. Medgyessy, who received his economist training at the Karl Marx University of Economic Sciences (today called Corvinus University of Budapest), was a Deputy Minister of Finance (1982–1986) then between 1986 and 1987 Minister of Finance of the Hungarian People’s Republic. While he was a member of the ruling Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party (MSZMP) from 1965, between 1987 and 1989 (that is until the system change and Hungary’s democratisation) Medgyessy also served in the highest MSZMP body, the Central Committee. After the collapse of the regime, he briefly abandoned his political career and worked in the banking sector.

Albeit Medgyessy was not a member of the MSZP (Hungarian Socialist Party, the successor of MSZMP), he was nominated as MSZP’s candidate for prime ministership to run against Orbán as an apparent technocrat, who could be trusted because of his financial expertise, despite his not-much-publicised career as a Communist functionary.

Medgyessy was also elegant and soft-spoken, and carried the surname of an old Transylvanian aristocratic family,

which made him more acceptable in the eyes of large swaths of the population.

To the surprise of many, the Socialists won the elections in 2002, probably also thanks to Medgyessy, who became Hungary’s prime minister heading a two-party coalition, composed of MSZP and the Free Democrats (SZDSZ), with some members of the Agrarian Alliance. While Medgyessy was quite popular initially, he was, in many ways, an outsider in his own party. His short-lived prime ministership is famous for the 2003 Hungarian European Union membership referendum that was coupled with Hungary’s accession to the bloc a year later.

On the other hand, he has become notorious as a result of his generous and therefore very costly social programme dubbed the 100 Days Programme. The left-wing government spent around 170 billion HUF on the programme, including 60 billion HUF spent on pensions, 18 billion spent on family benefits, and 92 billion HUF on raising the salaries of government employees. Albeit the programme was worryingly expensive, it greatly boosted the prime minister’s popularity. As a result, a second 100 Days Programme of a smaller scale was also announced, however, the government was forced to cut back on expenditure due to budgetary concerns.

Medgyessy was also an exceptionally bad public speaker, making frequent gaffes in almost every single speech.

Some of these instances of misspeaking have become proverbial, and only strengthened the perception of Medgyessy being a weak leader.

The downfall of Medgyessy’s prime ministership came in 2004, when a dispute arose between Medgyessy and one of the coalition members of its government, SZDSZ. At one point, Medgyessy accused SZDSZ with corruption in an interview, which did not go down well with the Free Democrats. At the same time, MSZP performed worse in the 2004 EP elections than Fidesz.

By that time, the government had run out of money and was forced to reduce public spending, for which many party members, especially the ambitious rising star of MSZP, Ferenc Gyurcsány, blamed Medgyessy. Ironically, Gyurcsány had served as Medgyessy’s advisor prior to turning against him.

As both coalition parties were dissatisfied with the prime minister, they conspired to remove Medgyessy. Finding himself in a vacuum, with his cabinet members deserting him, Medgyessy announced his resignation on 19 August, and resigned on 25 August 2004, that is 19 years ago. Despite the fact that he failed as prime minister, he kept his seat in the parliament as a representative until 2006; he was also the Travelling Ambassador of Hungary until 2008, visiting 44 countries around the world.

While Medgyessy’s resignation was the result of an quasi-coup orchestrated most probably by Gyurcsány, his departure was also the result of the fact that

his past as a counterintelligence officer of the dictatorial state socialist regime was uncovered.

As early as three weeks after his inauguration, information was leaked to the press about his role as an undercover agent in the so-called Department 3/2 (counterintelligence) of the Ministry of the Interior. Magyar Nemzet published a counter-espionage officer’s dossier under the code name D–209, whom the paper successfully identified as Medgyessy.

While initially the prime minister denied all allegations, later he was forced to acknowledge that he did work for the intelligence agencies before Hungary’s democratisation. Medgyessy argued that his only task was to identify risks and sources of danger to the country’s economy amidst its IMF accession which was opposed by the USSR and that he provided information to the agency only between 1977 and 1982.

Critics, however, highlighted the intertwining between the secret agencies of the various countries of the Socialist bloc and underlined that Medgyessy could have shared information with the agencies of the Soviet Union as well, not only with Hungarian agencies. Magyar Nemzet collected further evidence and accused Medgyessy of reporting about the ‘anti-revolutionary actions’ of his colleagues in 1976, undermining the prime minister’s claim that he spied only in the interest of his country. Medgyessy denied these accusations and named the love of his country as his primary motivation to work in counter-espionage.

The story was even covered by German weekly Der Spiegel, which suggested that European leaders were uneasy negotiating EU accession with a Hungarian prime minster who used to serve as a counterintelligence officer under the communist regime.

The ‘D–209 agent’ controversy sparked nation-wide debates and protests.

Founding president of SZDSZ, philosopher János Kis resigned from his role in protest,

arguing that governing with such a prime minister is immoral. Protestors blocked the Elisabeth Bridge, demanding new elections.

The information published by Magyar Nemzet and the disputes that it provoked revealed at least two things about post-communist Hungary. First, that decades after the regime change state socialism still had a lingering effect on the politics of the country: the question of collaboration with the regime and of the lustration that never happened after 1990 were still relevant.

Secondly, however, the scandal also showed that the regime change was not in vain, that freedom of speech and the freedom of the media were real. After years of a one-party state controlling the public sphere, Hungary did successfully democratise, and newspapers became strong and independent enough to do investigative work and provoke government crises and shape public discourse.