The Pulitzer Prize, the most prestigious award a journalist can be honoured with, was given out for the 107th time earlier this year. The winners of the very first awards of this kind were announced on 24 May 1917, in the midst of the Great War raging across the world.

The war, understandably, syphoned quite a lot of attention away from what later became a staple in the world of journalism, so the first Pulitzer Award Board actually struggled with too few entries. For this reason, they never gave out a Fiction Prize as they originally intended. However, they did give out the Editorial Writing Prize (to the New York Tribune’s staff for their writing on the anniversary of the sinking of the Lusitania, one of the events that prompted the United States to join the war), a category that still persists at the Pulitzer Prize ceremony to this day, over a century later.

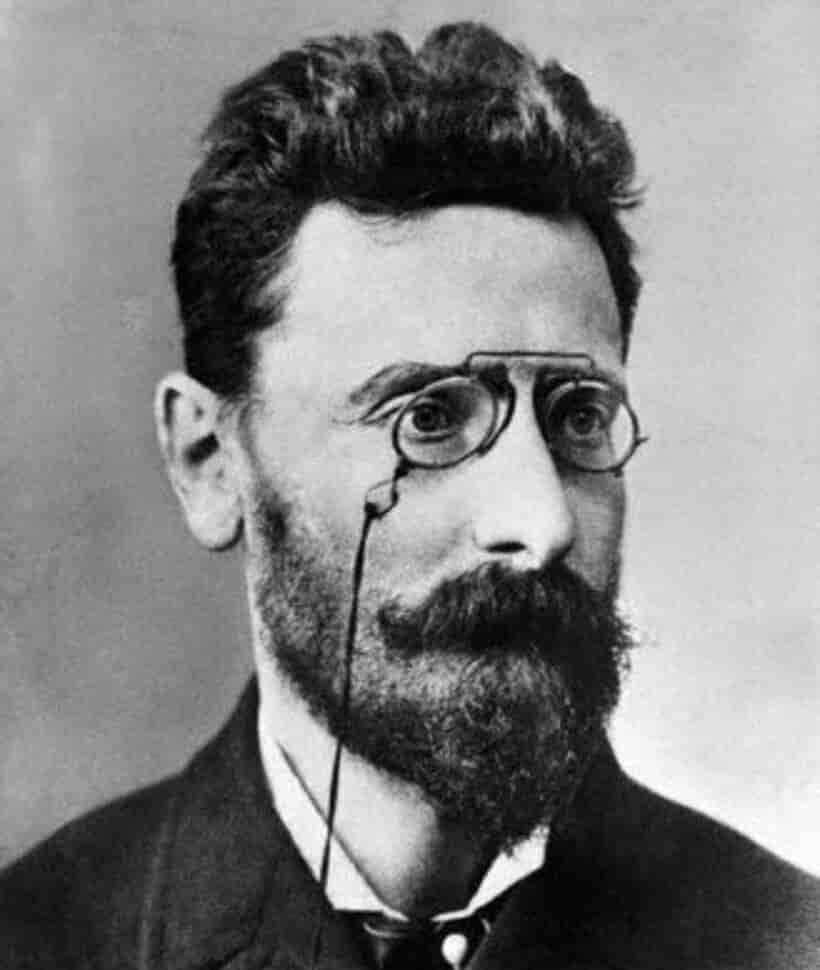

All this was made possible by

Joseph Pulitzer, a Hungarian immigrant and newspaper mogul, donating $1 million of his own wealth to Columbia University

to establish its Journalism School, on this very day 120 years ago, on 17 August 1903.

The Adventurous Life of Joseph Pulitzer

However, Joseph Pulitzer had to go through quite a lot to amass the immense wealth he donated that $1 million from.

He was born on 10 April 1847 in Makó, in the Kingdom of Hungary, which was part of the Habsburg Empire at the time. József, which was his original Hungarian name, was born into a family of wealth, his father being a successful merchant and businessman in his area. However, he died when József was only 11, and his tumultuous relationship with his stepfather, his mother’s new husband, led him to do anything that would enable him to leave home as a teenager. He tried enlisting in the Austrian Army and the French Foreign Legion, following in the footsteps of two of his uncles with military careers. However, he was rejected both times for his poor eyesight and weak, sickly physique. While trying his luck in Hamburg, Germany, he was at last recruited by the Union Army in 1864 to fight in the latter stages of the American Civil War.

Thus, in September 1864, a young József Pulitzer arrived at Boston Harbour, penniless and barely speaking a word of English.

He started off by breaking away from his Massachusetts recruiters, and travelling to New York so he can collect his whole $200 enlistment bounty for himself. He served in the 1st Regiment New York Volunteer Cavalry, known as the ‘Lincoln Calvary’, for the remainder of the war. He managed to complete his service unscathed, only seeing minor combat action. However, he still had a bad experience, as his fellow soldiers and officers constantly mocked him for his broken English and oversized nose.

After the Civil War ended with Pulitzer’s side, the Unionists’ victory, he remained in the US working odd jobs and often sleeping on the streets. His first journalist gig was writing a report of a fraud he fell victim to for the German-language St. Louis-based newspaper Westliche Post. While Pulitzer was cheated out of $5 by a conman who promised good sugar plantation jobs in exchange, but instead dropped them out in the middle of nowhere, this turned out to be a blessing in disguise for him. His report of his misfortune led to constant work as a journalist for him. He even met two ethnic German benefactors at the newspapers who helped him get some legal education, so he practised as a notary public for a brief time in Missouri. He even served a brief term in the Missouri State Legislature as a Republican, a short stint that ended with him shooting a political rival in the leg. The act ended up being judged as justified self-defence.

But it was clear all along that Pulitzer’s true talent and passion had always been journalism. In December 1878, he bought the newspaper St. Louis Dispatch for $2,500.

He managed to get the deal done for a relatively low price because the paper was going bankrupt. Soon after the purchase, the Dispatch merged with the St. Louis Post, becoming the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

Competing with two highly partisan papers in the city, the Daily Missouri Republican and the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, Pulitzer famously proclaimed in his paper that

‘The Post-Dispatch will serve no party but the people; be no organ of Republicanism, but the organ of truth; will follow no causes but its conclusions.’

His strategy worked, and the failing newspaper became a stable business under Pulitzer’s watch. The combined circulation of the Post and the Dispatch was 4,000 at the time of the takeover; by 1882, the Post-Dispatch’s had risen to 22,300.

However, the paper’s popularity took a big hit after another controversial shooting incident. This time, it was Pulitzer’s editor, John Cockerill who pulled the trigger, shooting lawyer Alonzo Slayback who came to the Dispatch’s offices to confront him about negative coverage about his law partner and political candidate James Broadhead. Slayback did not survive the shooting. While Cockerill too escaped charges on grounds of self-defence, Pulitzer and his paper’s reputation was irreparably damaged.

Thus, the Hungarian American media mogul travelled back to New York in 1883, where he purchased another publication to start afresh, the New York World.

It was there that his work ended up carrying the greatest influence. His new newspaper famously ran a fundraiser to erect the pedestal for the Statue of Liberty, without which one of the US’s most recognisable landmarks may not even be standing today, as New York Governor (and future President) Grover Cleveland was not actually too keen on accepting the gift from France.

On the more controversial side, the New York World also played a huge role in stirring up the hawkish nature of the American public after the USS Maine sank in Cuba under ambiguous circumstances, which led to the Spanish–American war in the late 19th century. Pulitzer also pioneered what later was dubbed ‘yellow journalism’, the predecessor of today’s tabloid journalism, at the World. This referred to the practice of seeking out odd, sensational stories (often from dubious sources and with questionable facts) in order to sell more copies.

Joseph Pulitzer passed away on 29 October 1911. In addition to his $1 million donation to Columbia University, the anniversary of which is today, he also allocated an additional $250,000 in his will to be used for a ‘Pulitzer Scholarship Fund’, as he put it, which later became the world-famous, much-coveted Pulitzer Prize.

Related articles: