In August 2021 then Fox News TV journalist Tucker Carlson during his visit to Budapest left some people perplexed when stated that ‘enlightenment liberalism…forms the basis of [his] politics and [his] worldview’. Was it a misunderstanding of the term on the part of the conservative pundit? Quite the contrary.

There is today a lack of a grasp of what is meant by ‘liberalism’ vis-á-vis ‘liberal’ democracy, where both are reciprocally linked. The common notion is that it is an anti-conservative doctrine. And while this is not false, it is also not true. Is the reason Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, during an interview with Bloomberg News in December 2014 stated:

‘At the philosophical-ideological level we feel that here in the Western world we are living in a ‘liberal non-democratic’ system…This is the ideology that

created its own language based on political correctness

and with this [language] established a grey, uniform approach to all questions…’

What then is liberalism? In order to comprehend its meaning, it serves us to appreciate the two government structures it finds itself in: parliamentary and presidential democracies.

Parliamentary and Presidential Democracies: The Differences

In a parliamentary democracy, which is essentially found in Europe, the power ultimately resides within the Party, not the People as with the presidential system in the United States. The Party winning the majority seats in the parliament makes the government and elects a person from among themselves as the Prime Minister who is the head of the Government. Consequentially, there is a very close relationship between the legislative and executive branches, as the head of the executive, often called the prime minister, is also a leader in the legislative branch. He is also accountable to the legislature. And even though he can dissolve the lower house—where there are two legislative chambers as in England—before the expiry of its term, only members of Parliament can be appointed as cabinet ministers.

Also, as it is in the United Kingdom ‘ministers—though all appointed by the premier—are at once mangers of the bureaucracy, the premier’s supporters (actual or nominal) and sometimes aspiring leaders themselves. Within cabinet, the dissent of an influential clique, or the machinations of a single magnetic personality, can limit the premier’s ability to pursue desired policy objectives. In extraordinary circumstances, a cabinet minister’s resignation many even threaten the premier’s hold on power.’[1]

In the presidential democracy found in the US, the President is the chief executive and is elected by the people through the electoral college, i.e., the States. The separation of powers between the legislative and the executive are far greater as he is not accountable to the legislative branch. He could neither dissolve it nor appoint a lawmaker to his cabinet unless that position is relinquished.

As it happens so often in Italy, the head of Government ‘may be brought down by either a parliamentary vote of no-confidence or a party munity…. If [Members of Parliament] fear that their party leader is growing personally unpopular, putting them at risk of losing their hearts in the next general election, they may attempt to elevate a new one’.[2] This is all non-existent in a presidential democracy.

In the US, the only manner to remove a president from office is either through the Senate’s confirmation of the House of Representatives’ impeachment or by invoking the Twenty-Fifth Amendment, by which the President or the Vice President and a majority of either the principal officers of the executive departments or of such other body as Congress provide a written declaration to the President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House that he is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office. In this case, the Vice President assumes the duties since he was elected by the People.

The Essence of Liberalism

The term ‘liberalism’ refers not to the matter of who rules but, instead to the way of how that rule is exercised. It implies that government is limited in its powers and its modes of acting, first by the rule of law, i.e., a constitution, and secondly by the rights owed to the individual. It is a political and moral philosophy based on the rights of the human person, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality, right to private property and equality before the law.

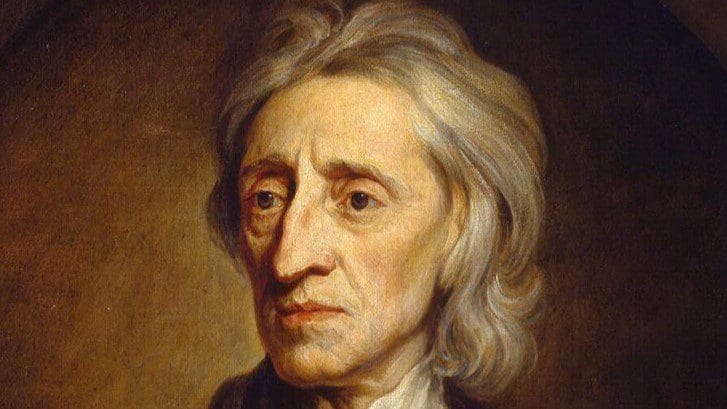

As John Locke wrote in his Second Treatise of Government,

we are all born into ‘a state of perfect freedom’

and thus man is free to do whatever he wills so long as it is ‘within the bounds of the ‘law of nature.’ In this state of equality, no man has a natural claim to rule over another:

‘…wherein all the power and jurisdiction is reciprocal, no one having more than another: there being nothing more evident, than that Creatures of the same species and rank promiscuously born to all the same advantages of Nature, and the use of the same faculties, should be equal one amongst another without Subordination or Subjection.’

The notion of rights originated with liberalism. The safeguarding of the natural inalienable rights of the individual as Thomas Jefferson wrote in the Declaration of Independence is the underlying element of a liberal political order.

The Present-Day Notion of Liberalism

In present-day America, and not just there, liberalism denotes support for an activist government and is characterized as the opposite of conservatism. A liberal would thus be someone who sees the principles of the natural law as restrictive in nature and purpose, hence the antagonist push for abortion, the LGTBQ+ agenda, open borders, and the like. Why such a departure from the original concept of liberalism? As Orbán explained in a 2022 interview:

‘Earlier, democracy itself was never subjected to labelling by anyone, because democracy is the soil from which the governmental policies of different ideologies grow and then compete with one another. In the early 1990s, however, liberals [the new left] realized that democracy itself had to be captured. [They] concluded that the object was not to win the debate over who could democratically enact better policies, but to seize democracy itself’.

In Europe the term liberal has been associated to political parties that support the free market without any surveillance and a more limited role for government, hence the position of the libertarians.

This is why the Father of the US Constitution James Madison, reflecting the essence of liberal democracy, wrote in the ‘Federalist Paper’, Number 10 against ‘the infirmities’ of ‘a pure democracy, by which [he meant] a society, consisting of a small number of citizens, who assemble and administer the government in person’. In a pure (or direct) democracy ‘there is nothing to check the inducements to sacrifice the weaker party or an obnoxious individual’, and therefore cannot secure the individual’s ‘rights of property’.

The classical notion of liberalism is today misunderstood, or rather it has been reformulated by the left-wing, i.e., the ‘false liberals’ in order to impose hedonist policies as human rights, and all under the pretext of promoting a free and democratic society.

It cannot be disputed that liberalism demands we remain open to hearing differences of opinions and the ability to mediate them through democratic institutions. Openness, however, does not equate to acceptance, especially if it is incompatible with the truths of the natural law, as John Locke had forewarned. Yet in our polarized society where vilification and the insidious submersion of politics in fact-lite entertainment have become the modus operandi of reasoning, it is understandable why liberalism seems to have altogether perished from the democratic realm.

[1] Henry Kissinger, Leadership: Six Studies in World Leadership. United Kingdom, Allen Lane/Penguin Random House, 2022, 324.

[2] Ibid., 325.