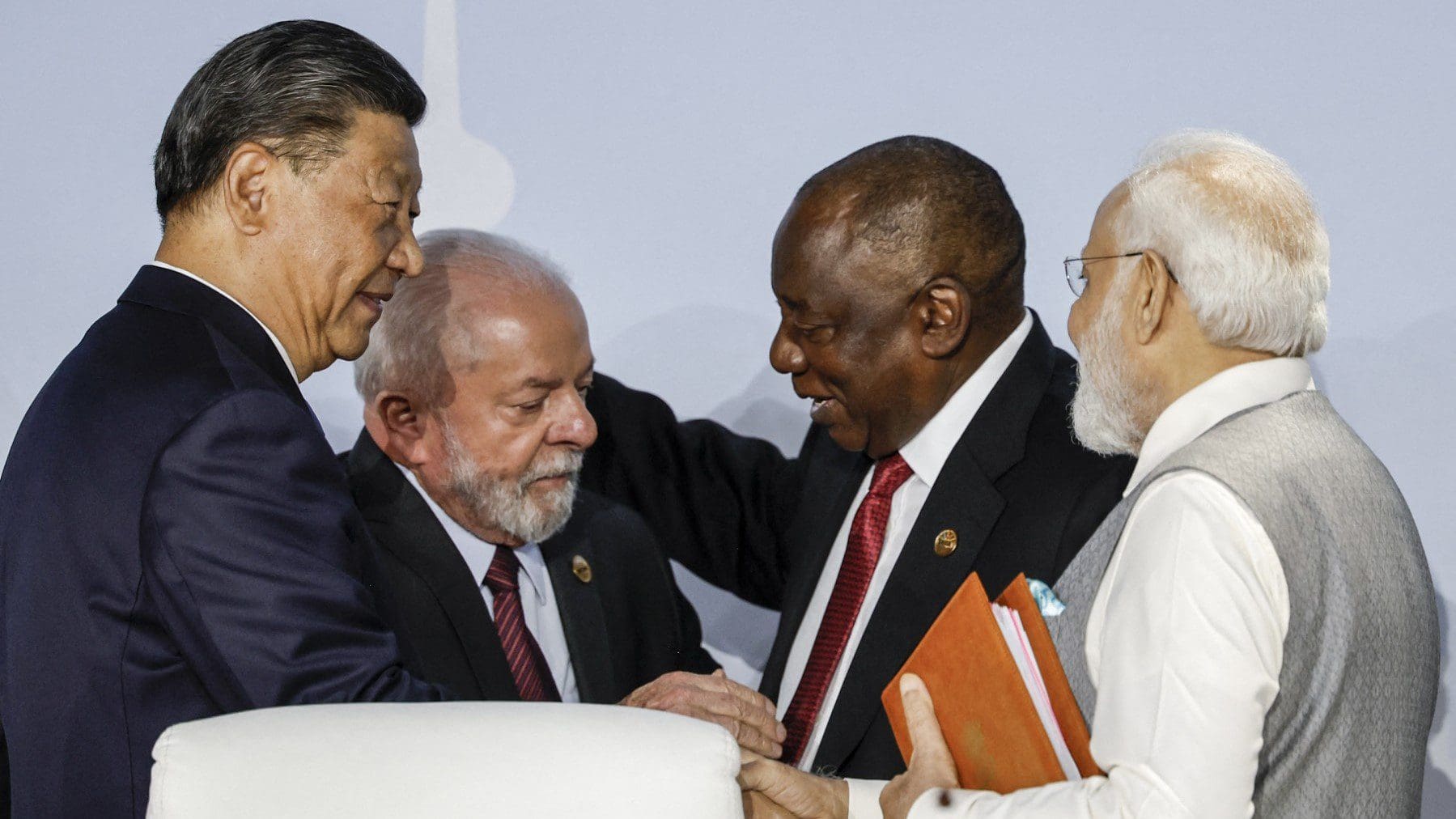

The BRICS nations held their annual summit at the end of August in Johannesburg, South Africa. As the columnist of The New York Times pointed out, because of the intensifying trade war between Beijing and Washington, and the continuing Russia-Ukraine war, the international interest in the latest meeting reached a level last seen in 2009, at the time of the group’s formation. After the global economic crisis in 2008, many commentators considered the official establishment of BRIC (initially the cooperation of Brazil, Russia, India, and China) as a significant moment in global trade and development. The goal of the arrangement is to restructure the global political, economic, and financial architecture. But to what extent has this been achieved so far?

Today BRICS accounts for 18 per cent of global trade, 23 per cent of global GDP, over 42 per cent of the global population, and 30 per cent of the world’s territory.[i] Despite these impressive figures, it became clear very quickly from the start that the cooperation of countries so different politically and economically was not so easily realised. In the 2010s, the economic growth of the group, excepting China and India, wasn’t significant. A few days before the recent gathering, The Economist published a review of the group’s previous results. It noted: ‘On average the GDP of Brazil, Russia, and South Africa has grown by less than 1% annually since 2013 (versus around 6% for China and India)’. As it is emphasized in the article: in 2001, China’s share of the BRICS output was as much as 47 per cent, and this has only increased. China today is responsible for remarkable 70 per cent of the group’s trade. In fact, even twenty years ago China accounted for more than half of all trade of the Group.

If we leave the context of BRICS aside for a moment and take a look at the indicators of the South-South cooperation, an initiative with similar objectives, but in a different framework, we can observe similar processes at work. Although the extent of South-South trade fluctuated until the end of the 1980s, from the 1990s it showed persistent growth, both on the export and import side. By the 2000s, its rate had doubled, and by 2010 it had reached 37.3 Southeast per cent.[ii] However, the engine of trade between developing countries is Southeast Asia, with a large share again contributed by China. Regarding China, it’s evident that

it effectively uses both South-South cooperation and BRICS to reduce its dependence on Western markets.

Part of this effort is to encourage trade in the local currencies of the BRICS countries. Several analysts pointed out that after the Federal Reserve raised interest rates in 2022, the dollar has gained against almost all currencies. The situation just became worse when the Russo-Ukrainian war broke out. BRICS countries, like all other emerging markets, were confronted with two unfortunate consequences: dollar debt is more costly for them to service, and the cost of importing goods has risen significantly. This process gave even greater urgency to the issue of ‘de-dollarization’ which has been part of the BRICS activities for years. Contrary to expectations the creation of a common BRICS currency wasn’t on the table at the 15th BRICS Summit. What might be expected in the future is the increased use of local currencies in trade, especially the Chinese renminbi, which is already becoming more common. In recent years, China has been able to establish cooperation with several African countries that are part of the BRICS-Africa dialogue to use the renminbi as a reserve currency.

It is no coincidence that China is most committed to the issue of expansion. Due to the war, the scope of Russia’s foreign policy has narrowed. Indeed, Putin did not even attend the meeting in person because of the international arrest warrant issued against him. At the end of the summit the admission of six new members—Iran, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Argentina, the UAE, and Ethiopia—was announced. However, it is clear that there are some controversial issues between the founding states regarding the nature of its expansion. Several people suggest that China is using the BRICS to gain influence and that the expansion mostly serves its interests.

The issue of the South-South cooperation and the rise of the Global South has been the subject of much discussion in recent years. Debate has focused on whether the emerging powers of the Global South

wish to redefine their positions in the existing system or challenge the structures of international capitalist development.[iii]

As some experts point out, BRICS deals with issues that were originally raised by the NIEO. For example, the reform of the IMF to give more leading positions to developing countries is very similar to the demands of the G77—the grouping of non-aligned states within the UN during the Cold War. The G77 and the NIEO (New International Economic Order—the idea was created at a United Nations Conference on Trade and Development in 1964 to express the demands of developing countries for greater influence in matters of international economic life) called for the reform of international organizations in the same way as BRICS does today.[iv] What we are witnessing is a restructuring in South-South relations. Although there is hope for the emergence of the so-called ‘South-South collective development paradigm’, there have also been criticisms of the current process. According to this perspective,

there is a new, Southern type of neo-colonialism,

which is exactly the opposite of the hope for a kind of collective self-sufficiency created by the Global South.[v]

In summary, we do not know what the future of BRICS will be. Although many people are sceptical about how states with such different political systems could represent a counterpower to the West, we should not forget that ‘five BRICS nations surpassed the G7 in terms of their combined GDP in 2020’. If we examine the combined GDP data at purchasing power parity, we have to face the fact that in 2010, there was a difference of almost 8 percentage points in favour of the G7. By contrast, in 2023, the BRICS managed to reach over 30 percentage points more than the G7.[vi] While there are signs of coordination of different policies within the group—like the diplomatic and foreign economic responses to the Ukrainian-Russian war—various efforts to gain influence and to enforce national self-interests are also evident. The wisest thing is to follow what the realist school claims about states. Both the G7 and the BRICS countries are led by self-interest. Superpowers are superpowers, whether they are Western or Eastern: they intend to expand their influence on the global stage. The lesson for Hungary is to maintain good relations with everyone, but defend oneself against all types of neo-colonialism, be it Western or Eastern.

[i] The official website of the 2023 BRICS summit, https://brics2023.gov.za/evolution-of-brics/, accessed 1 Sept. 2023.

[ii] Prema-chandra Athukorala, Shahbaz Nasir, ‘Global production sharing and South-South trade’, The Australian National University, College of Asia & the Pacific, https://crawford.anu.edu.au/publication/crawford-school-working-papers/10823/global-production-sharing-and-south-south-trade, accessed 2 Sept. 2023.

[iii] István Tarrósy, ‘A globális világrend és az Észak-Dél-kontextus’, Politikatudományi Szemle, Issues 2 and 3, Volume 15, 2006.

[iv] Kevin Gray, Barry K. Gills, South-South Cooperation and the rise of the Global South’, Third World Quarterly, 2016, Routledge, Vol. 37, NO. 4, 557-574

[v] ibid.

[vi] Felix Richter, ‘The Rise of the BRICS’, Statista (22 Aug. 2023), https://www.statista.com/chart/30638/brics-and-g7-share-of-global-gdp/