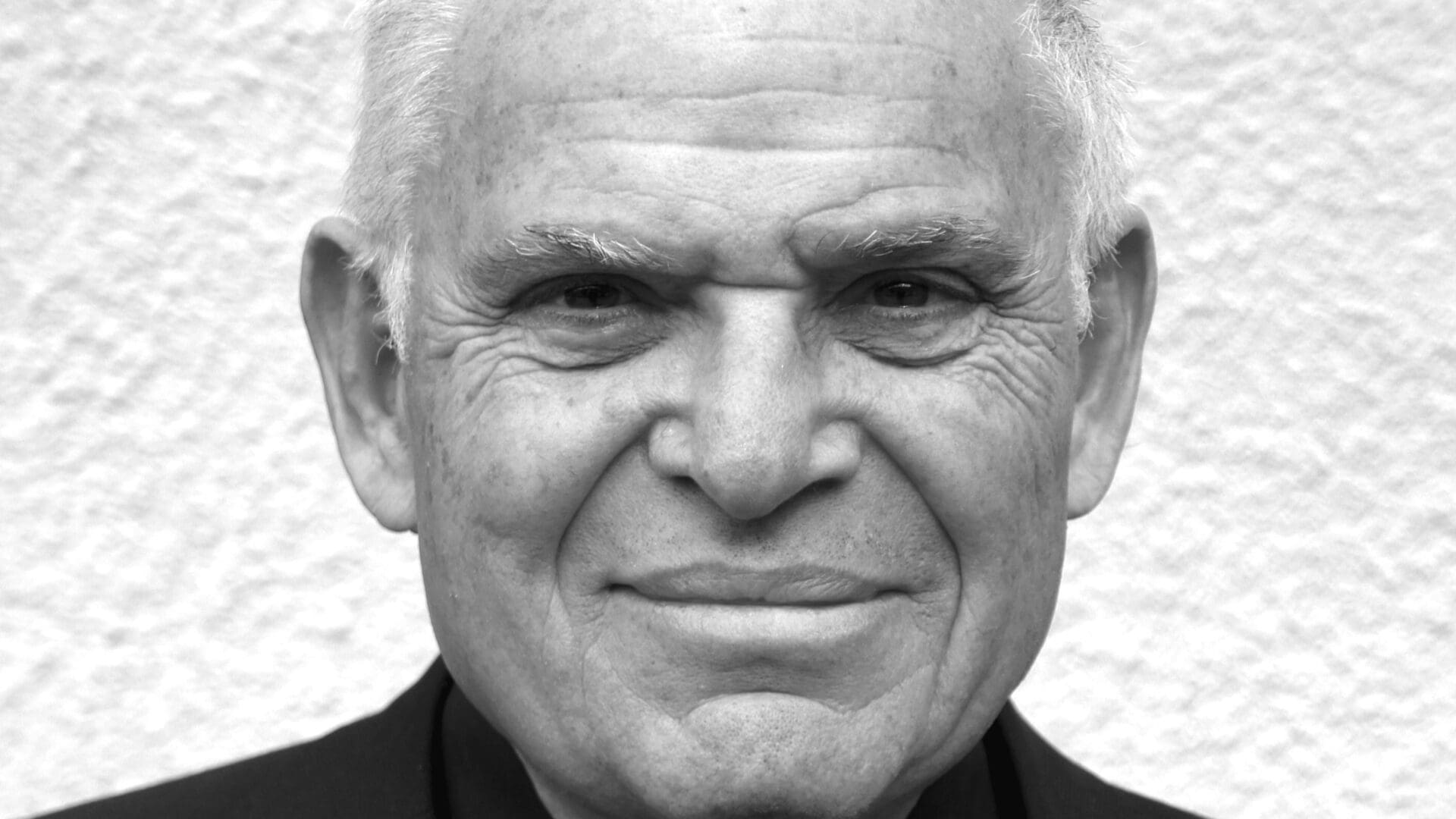

Edward Nicolae Luttwak was born in 1942 in Arad, formerly Hungary, now part of Romania, to a Jewish family. Despite being born in troubled times in a disputed region, he managed to get an excellent education at the London School of Economics and Johns Hopkins University in the United States. His personal experiences and education, combined with his involvement with three different military, the Israeli, the British and the American, turned him into an excellent strategic thinker, closely affiliated with and influential even in the Pentagon.

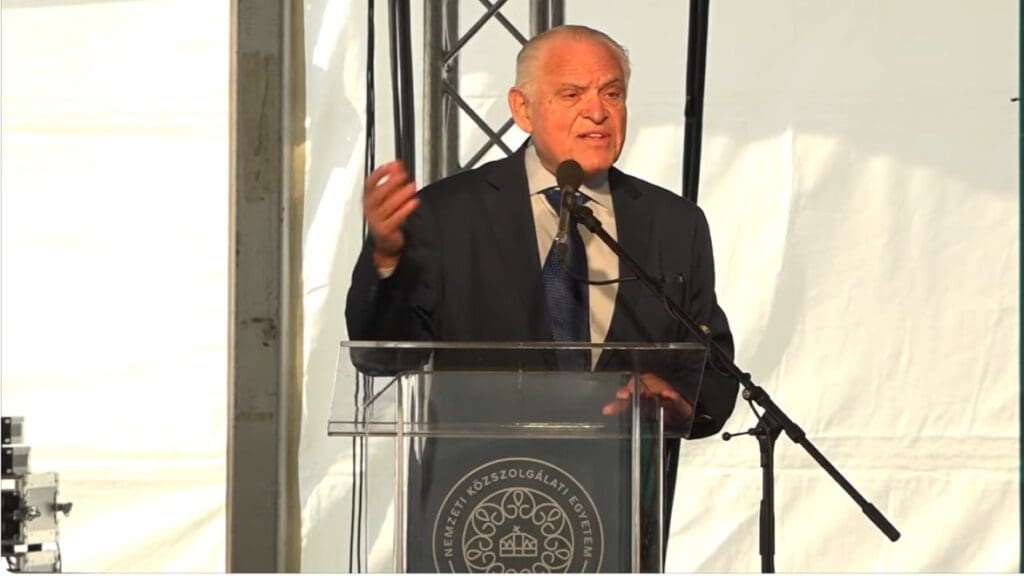

Luttwak visited Hungary in May this year when he met with students and faculty at MCC and delivered a lecture at the Ludovika Festival of the University if Public Service. Hungarian Conservative also had a chance to interview him during his May visit.

Edward Luttwak is not just a political advisor and scholar, but also a prolific author, with most of his books having become classics of modern strategic studies. In one of his first and most influential works, titled Strategy: The Logic of War and Peace, he said the following about his background:

‘Perhaps it is because I was born in the disputed borderland of Transylvania, during the greatest and most sinister of wars, that strategy has always been my occupation, and also my passion.’

In the aforementioned work, which was published in 1987 and for which he has gained notable acclaim, he aims to create a united, overarching view of the dynamics of armed conflict:

‘My purpose...is to uncover the universal logic that conditions all forms of war as well as the adversarial dealings of nations even in peace. Whatever humans can do, however absurd or self-destructive, magnificent or sordid, has been done in both war and statecraft, and no logic at all can be detected in the deeds themselves. But the logic of strategy is manifest in the outcome of what is done or not done, and it is by examining those often unintended consequences that the nature and workings of the logic can best be understood.’

Luttwak commences his book by highlighting the paradoxical nature of war, which, although appears to be obvious, is sometimes overlooked in discussions about the essence of warfare. Recognizing the paradoxical nature of all wars is the basis of analytical thinking about them, while it also strongly separates armed conflicts from the realm of peaceful life. War’s paradoxical nature can be metaphorically exemplified by the famous Roman proverb,

Si vis pacem, para bellum—If you want peace, prepare for war.

The paradox of war can be best explained in contrast with the choices one makes during his mundane peaceful activities. Consider two roads: one is paved and even, leading straight to the chosen goal, whereas the other one is mountainous, dirty, precarious and longer than the other. The question of which is preferrable to achieve a given goal is obvious—the paved road is the way to go. However, during times of war, deliberately paradoxical choices that appear to be worse, inconvenient and dangerous at first sight are generally more preferrable. As Luttwak explains:

‘Only in the paradoxical realm of strategy would the choice arise at all, because it is only in war that a bad road can be good precisely because it is bad and may therefore be less strongly defended or even left unguarded by the enemy. Equally, the good road can be bad precisely because it is the much better road, whose use by the advancing force is more likely to be anticipated and opposed.’

However, in war every decision has its price. The price of such seemingly paradoxical moves and decisions is the organizational, technical costs and other ‘friction’. Friction is the risks that may occur while implementing a plan, for instance, miscommunication, delays, mechanical, organizational or logistical breakdowns.

But the impact ‘friction’ might have on planning is observable in normal life, too. Luttwak gives the example of a family holiday going entirely wrong just because of a minor mistake. In war, the situation is aggravated by the army’s enormous resource-consumption, logistics and technology-dependent machinery that consists of hundreds of thousands, if not millions of people—each element in this immense machinery can easily malfunction, causing a cascade of side effects, affecting the entire endeavour. Not to mention that, as opposed to peacetime, there is an enemy—a malicious force that actively works on preventing the implementation of the desired plan. As a result, at times, the dynamics of opposing forces' efforts can lead to counterintuitive outcomes. For instance, there can be a strong emphasis on countering the enemy's advanced technology, leading to a successful effort in neutralizing it. Paradoxically, however, the fear of a dangerous weapon coupled with active efforts to counter it can inadvertently shift attention away from a secondary, less conspicuous weapon, allowing the latter to inflict significant damage on the enemy. This oversight occurs as the secondary weapon remains off the enemy's radar, and consequently, no countermeasure is developed against it.

Another interesting concept that Luttwak explores is that

excess victory can turn into a defeat, and a defeat into a victory.

He gives the example of the invasion of the Soviet Union by Germany in 1941. As the Germans advanced forward encircling the Soviets, they left enormous territories behind them. At the same time, the retreating Red Army pulled together its dispersed forces while also moved closer to its logistical centres. Besides, while the Soviets were learning a lot from their mistakes, the Germans, blinded by their triumphant march, did not. In addition, the Nazis’ successful campaign also overextended their logistical supply lines, and they were also forced to allocate a significant portion of their forces to govern the occupied territories, diverting them away from the front lines. By the time the German army reached the outskirts of Moscow, their victory had exhausted them. Defeat, writes, Luttwak, is a much better teacher.

The history of armed conflicts also reveals, argues Luttwak, that the effect of victories and defeats on the morale is not easily predictable. Victory can make the troops feel that they have already done enough, whereas there is a chance that the defeated would relentlessly sacrifice themselves to achieve the victory they have been longing for. To illustrate his point, Luttwak again cites a WWII example:

‘Combat morale defines not happiness but rather the willingness to fight. Victory may increase the former but reduce the latter: having just fought and won, the troops may both be happy and also feel that they have done enough. (Clausewitz described this phenomenon as ‘‘the relaxation of effort.’’) Such things are not easily proved, but military historians agree that the veterans of the British Eighth Army of the Second World War, who had long fought and finally won against the Germans and Italians in North Africa, were done with risky fighting by 1943; yet they had two more years of campaigning left, both in Italy and in northwest Europe after D-Day.’

With the aim of analysing the logic of war more thoroughly, Luttwak breaks down the broader concept of strategy into several levels: the technical, tactical, operational, war theatre and grand strategy levels. According to Luttwak, the eventual outcome of the war is decided on the grand strategy level, which is significantly intertwined with the political goals of the war. Political missteps such as untimely peace negotiations can abort even the most decisive victory and turn it into a failure. In other words, no single weapon or strategy can on its own determine the outcome of a war—something it appears we are seeing happen in the Russo-Ukrainian war:

‘As soon as a significant innovation appears on the scene, efforts will be made to circumvent it—hence the virtue of suboptimal but more rapid solutions that give less warning of the intent and of suboptimal but more resilient solutions. This is why the scientist’s natural pursuit of elegant solutions and the engineer’s quest for optimality often fail in the paradoxical realm of strategy.’