This year marks the tenth anniversary of when Chairman Xi Jinping announced his Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) enterprise. Viewed as the largest and most ambitious infrastructure development undertaking in human history, China sought to improve connectivity and cooperation on a transcontinental scale with more than 150 countries and over 30 international organisations. China’s ambitious project has raised grave concerns among competitive countries, the United States in particular, as Beijing has lent more than $1 trillion to more than one hundred countries, curbing Western spending and investment in the process.

Many analysts have described Chinese lending through the BRI as ‘debt trap diplomacy’ designed to give them leverage over other countries and even seize their infrastructure and resources. This ‘debt trap’ rhetoric has been rejected by Dennis Munene Mwaniki, Executive Director of the Africa Policy Institute, saying it is ‘more of a political narrative and propaganda pushed to discourage Africans from working with China’.

Chinese enterprises have dominated, for example, the financing and development of critical infrastructure in Africa since 2017. The Infrastructure Consortium for Africa estimates that in 2018, China contributed $25.7 billion of the overall $100.8 billion committed towards African infrastructure development projects. The African continent is rich in natural resources, yet, because of corruption political instability, and other factors, most African countries lack adequate and reliable infrastructure necessary to boost economic development. Through the BRI, the continent was able to have more than 100 thousand kilometres (62 thousand miles) of highways, some 1,000 bridges, and 100 ports built that had been under construction, with a large number of employments being created.

When Xi launched the BRI, he believed it would allow his country to more efficiently utilize excess savings and construction capacity, expand trade, consolidate economic and diplomatic relations with participating countries, and diversify China’s import of energy and other resources through economic corridors that circumvent routes that are controlled by the US and its allies. Given its precarious hegemonic control of BRICS,

China both believed and tried, as the World Economic Forum compulsively stated in 2016, to supersede the US and become the world’s greatest economy.

Not only has this not happened, but, over the last few years, in what many characterize as an economic-colonial despotism, a different picture of the BRI and China’s lending institutions has emerged as its economic growth is slowing down and becoming fragmented.

Failed Acumen

Many Chinese-financed infrastructure projects have failed to earn the returns expected from the BRI. In addition, since governments, like Sri Lanka, Argentina, Kenya, Malaysia, Montenegro, Pakistan, Tanzania, and many others that negotiated these projects often agreed to backstop the loans, they have found themselves burdened with huge debt overhangs—unable to secure financing for future projects or even to service the debt they have already accrued. In fact, as reported by Euronews just a few days ago, Italy has indicated that it expects to leave China’s ambitious but troubled BRI—a high-profile reminder that the initiative has failed to meet its goals.

Research scholars Michael Bennen and Francis Fukuyama explained that the wave of debt crises may be far worse than previous ones, inflicting lasting economic damage on already vulnerable economies and miring their governments in protracted and costly negotiations.

While some analysts put more of the blame on bondholders or multilateral lenders, such as the IMF and World Bank than on Beijing, a 2021 study in the Journal of International Economics demonstrates that approximately half of China’s loans to the developing world are ‘hidden’, i.e., they are not included in official debt statistics.

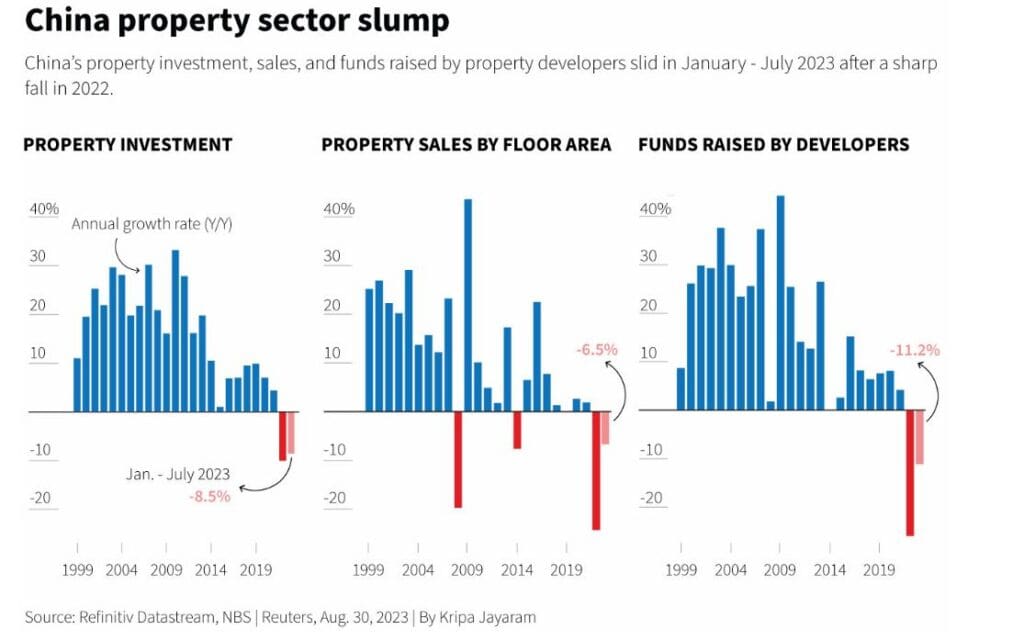

Another study published in 2022 by the American Economic Association found that such debts have resulted in a series of ‘hidden defaults’. Also, throughout the Global South, BRI agreements have hardly achieved anything but funding corruption, building faulty or unneeded infrastructure, and contributing to a massive new debt burden for low-income countries already struggling to fund basic services. Together with the real estate crisis that has left millions of empty apartments in major Chinese cities, and Country Garden, China’s largest surviving developer further sinking into debt,

it could very well be as President Joe Biden said of China’s economy: it is ‘a ticking time bomb’.

In addition, unlike Western consumers who were subsidised to one degree or another, Chinese citizens were left largely to fend for themselves during the COVID-19 pandemic. Also, the revenge spending spree that some economists expected after China re-opened never took place. Moreover, demand for Chinese exports has decreased as key trading partners have been grappling with rising living costs. And with 70 per cent of Chinese household wealth tied up in real estate, a big slowdown in the sector is trickling through to other parts of the economy.

China’s financial stagnation, according to a recently published article by The New York Times, is perhaps the most sustained challenge to Xi’s decade-long economic agenda. While he steered it out of an old era dependent on real estate and smokestack industries to a new one driven by innovation and consumer spending, consumers are gloomy, private investment is sluggish, there is a near collapse of big property firms, local governments face crippling debt, and youth unemployment has continued to rise.

Indeed, things are getting so difficult for Xi’s authoritarian directives that, according to an exclusive report by the Wall Street Journal, in an effort to cut reliance on foreign technology and enhance cybersecurity, Beijing ordered officials at central government agencies not to use Apple’s iPhones and other foreign-branded devices for work or bring them into the office.

China’s economy actually fell into deflation in July, while factory-gate prices also extended declines—its debt is three times its GDP in 2022. Beijing’s consumer price index, the main gauge of inflation, fell 0.3 per cent in July, the National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBS) said, after having flatlined in June. A survey of analysts had anticipated a 0.4 per cent year-on-year decline.

In 2021, Chinese exports to Central and Eastern European countries (CEE) totalled 461.05 billion yuan, up 25.3 per cent, while imports from CEE countries totalled 168.36 billion yuan, up 32.5 per cent. Despite the limited economic size of CEE countries, the growth of economic and trade cooperation between China and CEE countries has been higher than that between China and the EU. Yet for trading partners in the CEE, such as Hungary, which is one of the top three CEE trading partners with China—the other two are the Czech Republic and Poland.

Indeed, despite the G20 countries, which Hungary is part of, proposing the Global Gateway to counter the BRI, Dr Norbert Csizmadia, former state secretary in charge of planning coordination for the Hungarian Ministry for National Economy stated:

'Hungary serves as a strong gateway between the West and the East, boasting robust political and economic stability, a distinct cultural identity, strong connectivity, and a well-established industrial base…..It is very important to understand geopolitics in the right way….I don't see it as an alternative. It reflects a Western perspective. China's approach is about cooperation, connectivity, and a peaceful win-win situation. I recall the first EU-China Forum in 2018, which was crucial. The EU’s Global Gateway proposal, following the BRI, might be problematic in terminology. "Belt and Road" signifies connectivity, while "Gateway" implies merely an entry point'.

China, instead of celebrating ten years of cooperation with CEE, known as 16+1, as of last year, is desperately seeking to salvage its relationship worsened by the war in Ukraine. Perhaps more unexpectedly for Xi, the Chinese economy continues to be outdone by the US in dollar value, despite Beijing holding about $859.4 billion of US debt—the total US national debt is $32.5 trillion. In 2022, China's gross domestic product was $18 trillion, compared to $25.5 trillion for the US.

The Beginning of the End?

Economists say that China could, in theory, turn things around if it were to provide government-funded consumer vouchers, introduce significant tax cuts, encourage faster wage growth, build a social safety net with higher pensions, improve unemployment benefits, and the like. The dilemma is the elephant in the room, Xi Jinping.

As with every authoritarian leader, the Chinese Chairman is now imposing his cult personality on his subjects.

Known as the Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era, or Xi Jinping Thought for short, Xi’s writings and speeches must be both studied and implemented within the educational, financial, and government sectors in order to arrive at a greater ideological purity based on the party’s Marxist-Leninist roots. All of those oppose the aforementioned suggestions.

Xi’s doctrine, notwithstanding its appeal for greater economic and social equality, can in practice mean steep cuts to the salaries of high-performing employees. According to Carsten Holz, an associate Professor of Social Science at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, the Xi Jinping Thought's tenets directly and negatively affect the open exchange of ideas and the free-spirited innovation that drives economic growth.

Indeed, it could distract China’s banks and state-owned enterprises from the most important task at hand—namely, getting the economy back on track as its post-pandemic recovery stumbles amid challenges including deflation, a real estate crisis, and a low birth rate.

Related articles: