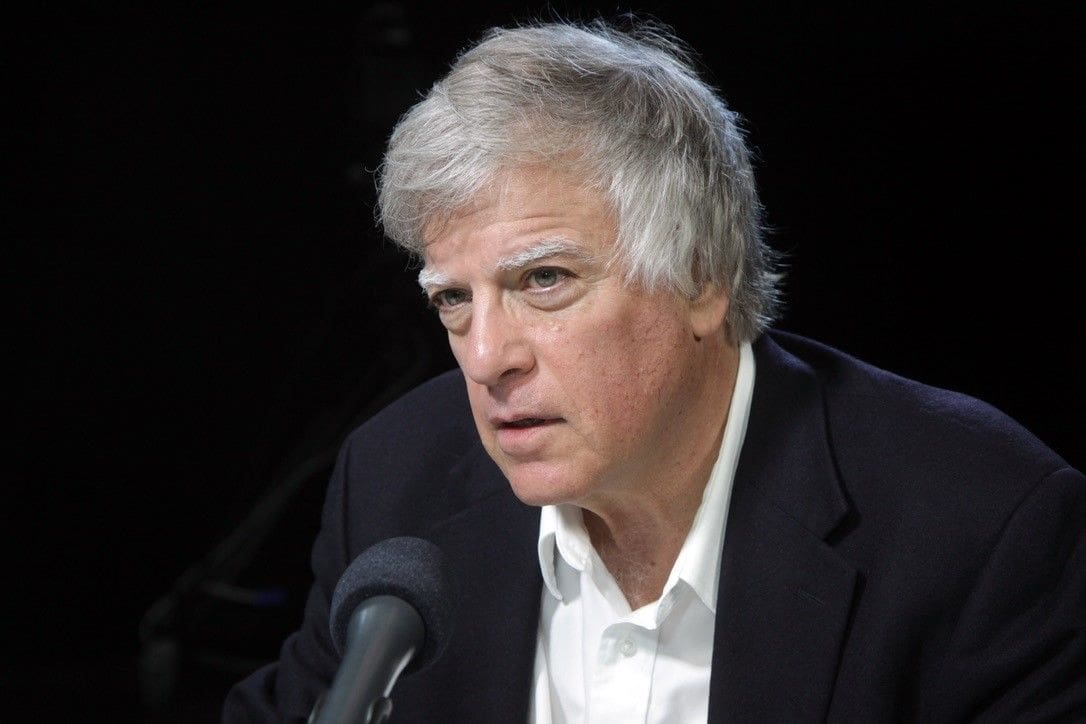

David Satter is a renowned American journalist, historian, author of six books and one of the world’s leading experts on the Soviet Union and Russia. He is known to be one of the longest serving Western correspondents in Moscow during the Cold War and – perhaps not incidentally – the first foreigner to be expelled from Russia since the collapse of communism. Recently, as a guest of the Danube Institute, Satter held a series of lectures in Budapest and I took the opportunity to ask him about his experiences of totalitarianism, today’s Western zeitgeist and the worrying tendencies we see in Putin’s Russia.

When and how did Russian studies peak your interests?

It began when I was a high school student, because the Russian language was offered as an elective in the high school that I went to. It was an unusual situation. And this was the time of the Cold War and the Soviet Union was the major issue for the United States. So, it was a combination of the fact that I began to become involved with the Russian language and my long-standing interest in the Soviet Union that led me to try to perhaps become a correspondent.

You’ve spent six years of your life as a Financial Times correspondent in Moscow. You published most of the experiences you’ve gathered during that time in your book Age of Delirium, and then in the subsequent documentary. Can you summarize the message of that book?

The message of the book is that communism and, in fact, any totalitarian system, is the tyranny of a false idea.What existed in the Soviet Union was the attempt to impose by force an entirely false interpretation of reality. The core of the Soviet system of control was control over people’s minds. As soon as the truth began to penetrate a world that was based on lies, either the truth had to be suppressed, or the world that was constructed on the basis of lies, would collapse.

This kind of ideological thinking has been gaining more and more traction in the West lately. Do you think what’s going on in progressive circles and academia is similar to what you’ve experienced in the Soviet Union?

It’s different in many ways. First of all, it’s voluntary. What existed in the Soviet Union was imposed by force. But so called “wokeism” does represent the readiness of people to live in a world of their own creation, a world that doesn’t conform to reality, and that they find either emotionally or psychologically comforting. People are ready to sacrifice their individuality and their critical judgment on behalf of a false construct that’s being perpetuated with the help of a herd mentality.

How did you feel when the Soviet Union fell? Were you in Moscow then?

I was coming in and out. I was there after it fell and before it fell. It was the end of an era. It was the end of the era of social revolution. It was the end of the era of totalitarian ideology based on social and racial conflicts. Unfortunately, the values which withstood the pressure of a totalitarian onslaught in the twentieth century are now the subject of attack. Instead of being strengthened, instead of societies trying to reinforce those values that had preserved civilized society in the face of such horrors as communism and Nazism, we’re now in the process of seeking to undermine those values on the basis of concocted ideas that don’t conform either to empirical reality or common sense.

Do you think that because of this process totalitarianism can return in the future?

These ideas are not being perpetuated through violence

These ideas are not being perpetuated through violence, at least not now. And there are – in the Western societies – institutions that are capable, theoretically, of containing them. And, in fact, they do not have the universal pretensions of Nazism or communism, which claimed to be systems of total explanation. They’re generally based on reactions to one or another social condition, whether it’s perceived inequality between the sexes, or between the sexual majority and sexual minorities, or between races. And therefore, they don’t have the same potential for destruction that communism had, which was an entire alternative interpretation of reality. Nazism was as well. Nazism, of course, didn’t have the intellectual quality of communism, but it was kind of an ersatz version applied to racial categories. What we have in the United States, Britain, other Western countries, is the ideologization of fairly partial, social and political claims. Unlike totalitarian ideologies which were upheld by force, these positions are debated. The debate is often pretty meager and one side tries to suppress the other, but fortunately the dominant version doesn’t have an army on its side– at least not for the moment. Nonetheless, they can do a lot of damage to the integrity of our institutions.

When the Soviet Union collapsed, did you see what Russia would become in ten or twenty years?

I feared that the criminal elements would come to the fore. And I feared that neither the US nor other Western countries would really understand what was necessary for Russia. What it needed was rule of law. But rule of law is based on the recognition of some higher values. The supremacy of law over the individual – and its equal application – is an expression of the equality of human beings before God. So, it always has a transcendent, other-worldly point of reference. You can’t make a state based on law in a society, which is organized on the assumption of the superiority of one racial or economic group or the interests of one political faction.

Can you define what kind of regime Putin’s Russia is? And can you tell me how could the Russian society let it come into existence?

It is an authoritarian criminal regime, which is based not on an ideology, but on the criminal theft of property and the concentration of power. It emerged as the Russian society became criminalized because the effect of communism on people’s psychology was really devastating. It confused them about the difference between right and wrong, and created a situation in which people didn’t feel that their individual conscience amounted to anything. The animating factor in the Soviet Union was Marxist-Leninist ideology. When the Soviet Union fell, the animating factor in the policies of the leadership became the concentration of wealth in the hands of a very small, corrupt group. No matter how they justify it, that is what’s ultimately at stake. They seek to make sure that this small group holds power, monopolizes wealth and can’t be overthrown.

You were the first prominent Western journalist to write about the 1999 apartment bombings being possible false flag operations to justify the Chechen War. After you started writing about this, did you at one point or another fear for your own safety?

It was a consideration, especially when I saw what happened to the other people who were writing about it, and they were killed. But I felt I was protected to a certain degree by being an American citizen. And I think that’s the case. And also, by being somewhat prominent in this field. But of course, it was a risk.

How did you feel when you found that you got expelled from Russia in 2013?

Well, it had a bad effect on my plans, because I was intending to stay there, and I wanted to stay there, but in a way, it wasn’t a surprise. They had long tolerated me and even pointed out to other correspondents, that their willingness to tolerate my presence was a reflection of the fact that they had a new attitude toward the press compared to the Soviet period. But I guess that new attitude didn’t survive as various experiences put them under stress. Still, I’m waiting the day when it will be possible to go back.

You’ve recently published a new book, Never Speak to Stangers, which is a collection of essays and articles published by you over four decades of writing about Russia and the Soviet Union. Is there a particular message of this book you’d highlight?

Well, it’s the same thing. The primacy of ideas, the importance of defeating an ideological attack by discrediting the underlying idea, the inability to create a democracy without a firm basis and decent universal values. That’s all in the book.

Do you think that a better education on the history of totalitarianism is needed for today’s young people?

Unquestionably! This is the missing element. This is the reason we go astray so often. We don’t have that necessary point of reference. Many members of the younger generation don’t understand what is possible, what, in some cases, their grandfathers or fathers went through. Their focus is very narrow. And they look for enemies within their own society without realizing that the true threat comes from outside. I like the idea of young people actually trying to out-think those who have adopted a herd mentality and trying to understand the movement of history.

Lastly, can you tell me about your upcoming book, which is still in progress?

It’s a history of Russia after the fall of communism. I want to answer all the unanswered questions. I want there to be a book that tells the full story. Including the story of the apartment bombings, the shooting down of the Malaysian airliner, the murders of the ‘dissidents’ and Democratic leaders in Russia.