The following is an abbreviated version of two articles by Ferenc Bónis, originally published on HungarianReview.com, which we are sharing to mark the passing of the great Hungarian composer 78 years ago today.

***

‘I can’t live without the sound of music’. This line from a Hungarian song which Zsigmond Móricz, Bartók’s famous contemporary, gave as the title to one of his novels and which so aptly characterized the gentrified world he was describing, is equally characteristic of the environment into which Béla Bartók came into the world on 25 March 1881 in the town of Nagyszentmiklós, Torontál County, Austria-Hungary (now Sânnicolau Mare, Romania).

What was this ‘sound of music’ like that one cannot live without?

The earliest compositions that the young boy wrote from the age of nine provide the answer: Waltz, Mazurka, Katinka Polka, Jolán Polka, Circus Polka. Short dances, character pieces, name’s day ditties—the fashionable light music of the age, and he also listened with pleasure to the Hungarian songs and csárdás repertory of the Gypsy bands.

Music was present throughout his father’s short and his mother’s long life. Before she got married, his mother finished a teachers’ training school, whose curriculum—back then—included learning to play a musical instrument. In any case, a young girl’s education would not have been complete without learning to play the piano. His father organized a music association in Nagyszentmiklós, of which he was president; and in order to participate in the orchestra, he learned to play the cello. After a while, Béla Bartók Sr (1855–1888) also tried his hand at composing short pieces himself.

His son was seven and a half when he lost his father. His mother, as we have mentioned above, was given the gift of a long life. From 1857, which saw the aftermath of the defeated Hungarian freedom fights against the Habsburgs, to 1939, which ushered in the Second World War, she lived eighty-two years. Her son, the famous composer and pianist, nourished the closest bonds with her.

According to family lore, the Bartóks received a title of nobility, and though there are no written documents to prove it, the budding young musician signed some of his early compositions as Béla von Bartók. Still, whether with or without a title of nobility, the father, who had graduated from the agricultural academy, was raised thereby to the status of an intellectual and lived the life of the rural petty nobility.

CHILDHOOD: ILLNESS, SOLITUDE, MUSIC

When he was just three months old Bartók received his smallpox vaccination—and because of improper hygiene or some other cause, we shall never know, he got a rash on his face which later spread over his entire body. The child was plagued by a terrible itch until he was five, which let up somewhat only when he had a fever. When he was better and his fever subsided, his suffering returned. His parents took him to Budapest, but consultation with physicians in the capital did not bring relief either. Consequently, the young boy experienced enough solitude to last him a lifetime. According to his mother’s recollections,

‘The poor child hid from people as it hurt him when they were always saying, “poor little Béluska!’” With the approval of his parents, one of his physicians tried treating him with arsenic drops, which finally did the trick, and ‘his face and his whole body cleared up and that terrible and painful rash never came back. ‘He spent nearly his entire kindergarten years without playmates, ‘he didn’t play with other children; he was a very serious, quiet child’.

He began talking conspicuously late—at the age of twenty-seven months. On the other hand, he discovered the communicative power of music conspicuously early. He liked listening to his nanny sing.

Another illness: a long-lasting, stubborn inflammation of the bowels followed. The mother’s next recollection brings news of the little boy’s musical activities. ‘When he was three, he was given a drum as a present, which made him very happy; when I played the piano he’d sit on his little chair, his drum was in front of him on a low stool, and I gave the precise tempo; if I switched from 3/4 to 4/4, he stopped playing on the drum for a moment, then continued in the proper rhythm.’

One year later he was familiar with the piano keys and had a memory that belied his tender age.

‘At the age of four, he played the folk songs he knew with one finger on the piano. He knew 40, and if we gave him the first words of the song, he played the tune straight away.’

Béla Jr’s joy lasted six months at most. ‘When his rash disappeared, he often suffered from bronchial catarrh…Once when he was five and a half, the doctor diagnosed scoliosis. We were terribly worried. On doctor’s orders he was not allowed to sit down; he even stood at the table. If he was tired, he had to lie on his back on the floor, where we put a carpet down for him. Of course, this was very bad for him because he couldn’t play lying down…”

In short, the child could not play the piano—yet another dose of solitude and exclusion, not his last—from what made him happy. A physical examination in Budapest altered the diagnosis and curtailed the therapy, but his catarrh, inflammation of the tip of the lung, reappeared. The catarrh became his constant companion and at times openly, at times dormant, it accompanied him for a long time, casting the shadow of death over him at an early age.

In 1887, he went with his father to Radegund, Styria, where he was much improved by the cold-water cure which, however, did not help his father, who died a year later, but not before he received proof of his son’s extraordinary ear for music.

‘When he was seven, we put his ear for music to the test and were delighted to learn that he had perfect pitch; he was next door and he could immediately name every piano note, he could even recognise simple accords.’ In one of his earliest compositions there are references to Radegund, but his father was not fated to hear it, along with all other proofs of his son’s talent as a pianist and composer. He died on 4 August of the same year, and for months the sound of music was gone from the home of the Bartóks.

One cannot help but wonder what shape the young Bartók’s musical career would have taken had his father lived longer.

Would he have realized that his own artistic ambitions, which had to remain dormant, could be fulfilled through his son? Would he have become, like Leopold Mozart, the one to discover and take news of his son everywhere, teaching him and getting back the effort of his labours with interest? Or, insisting on the inherited circumstances of his own life, would he have thought of his son as the successor to his post as president of the Nagyszentmiklós Music Society, which to him stood as the symbol of the best musical career that could be achieved under the circumstances?

The father’s loss and with it the loss of the family’s financial stability forced the survivors to make a new way of life for themselves,

and from one day to the next, the mother, who had been an exemplary housewife and self-effacing nurse, was now the breadwinner and head of the family. But the children also had to do their share, and with good conduct and high marks, they were exempt from having to pay tuition.

Had they remained in Nagyszentmiklós, the town would have made them ‘soil-bound’ in more than one way. But now, having been chased out of ‘Paradise’, like it or not, the world opened up before them. The road they were forced to take was no doubt bumpy, full of potholes and hurdles.

In October 1888, the family had to leave the apartment that the agricultural school had put at their disposal while Béla Bartók Sr was headmaster. For a time they remained in Nagyszentmiklós in a rented apartment, with the mother earning a living by giving piano lessons. Then with the beginning of the school year, she started teaching once again and they moved to Nagyszöllős in Ugocsa County.

The teacher’s diploma she had acquired now proved to be her life belt; in fact, her own daughter and later one of her granddaughters also became teachers. On the other hand, there was no musical life in Nagyszöllős, so the mother continued teaching her son the piano as long as she could. She also had to find a satisfactory solution for her son’s schooling, because due to the earlier exceptional conditions at home, he could not start school when he became of school age.

He began school when he was seven; on the other hand, by the time he was eight, he finished the first four years of elementary school with top grades.

However, his mother let him repeat the fourth year in Nagyszöllős (now Vinohradiv, Ukraine). This small town was the scene of one of the turning points in Bartók’s life.

According to his mother’s recollections,

‘Once when he was nine, while I was napping in the adjoining room after lunch, a melody was taking shape in his mind that he’d never played or heard before; he couldn’t play it on the piano for fear of waking me, but when I woke up, he told me about it. He played it for me at once, and it was a waltz, but entirely different from anything he’d heard before; from then on, he composed various dance pieces and others, too, in quick succession; this was his greatest enjoyment and our greatest joy.’

In his brief 1918 autobiography, Bartók provides further evidence of this, with a subtle reference to the limits of his mother’s prowess at the piano: ‘When around nine years of age I began writing short pieces for the piano and at the same time outstripped my piano teacher, we thought it important that we should move to a bigger city where I could further develop my knowledge of music.’ The choice fell on Pozsony (now Bratislava, Slovakia) which was close to Vienna and at the time enjoyed the most vigorous musical life among Hungarian towns.

His mother received a permanent teaching appointment at the women’s teacher training school in Pozsony, where she remained a highly respected teacher until her retirement. Her son’s grammar school years ended with his graduation in Pozsony in 1899.

After he ‘outstripped’ his piano teacher in Nagyszöllős, Bartók had no one to take lessons from, not even in Beszterce (now Bistriţa, Romania). In Nagyvárad (now Oradea, Romania), on the other hand, he found an outstanding teacher – if only for a couple of months – in the person of the composer and choirmaster of the cathedral, Ferenc Kersch, who to his pupil’s ill luck, wanted to turn him into a wonder child, and in his over-eagerness, overburdened him.

He found a really good teacher only in Pozsony, where first Lajos Burger, then László Erkel, one of Ferenc Erkel’s sons—Ferenc Erkel was lauded as the founder of Hungarian national opera and the composer of the National Anthem—took charge of his musical development.

László Erkel taught him not only the piano, but harmony and music history as well; when he died in 1896, Antal Hyrtl took charge of his musical education. From fifth grade until he graduated, Bartók played the organ at student masses.

From then on Bartók was a good student at grammar school; he received an award, a grant or a scholarship every year. His mother, who continued to live under humble circumstances, later prepared an account of these. Between 1894 and 1907 her son received support in the sum of 5,651 forints or 11,302 koronas which, even if divided by fourteen years, in the times of Franz Joseph was an appreciable sum of money, and Bartók’s mother was proud and appreciative of her son’s achievement.

Soon, the young Bartók’s musical talent was acknowledged by all of Pozsony.

But there was someone whom they thought even more highly of and with whom Bartók’s relationship was anything if not ambivalent—Ernst von Dohnányi, who was four years his senior and who survived him by fifteen years. Dohnányi was a phenomenal pianist with an astonishing ear and memory; when Bartók was still attending grammar school, Dohnányi was already well-known nationwide and was touring the world. As a composer, he was a follower of Johannes Brahms, who was considered too modern at the time, especially in Pozsony, and the proverbially impolite Viennese master spoke of his first opus in glowing terms of praise.

The young Bartók considered Dohnányi a paragon of sorts whose he should follow. But at the same time, his very existence was a challenge—someone who is stronger, someone he must wrestle with, someone he must one day get the better of. Later their paths diverged; Dohnányi became the Hungarian master of German late romanticism while Bartók, ‘the hero of tomorrow’, set his sights on more and more distant shores.

As a pianist he did not manage to ‘outstrip’ Dohnányi, but in the infinite spaces of music history, as a composer he outstripped him by many light-years.

This, however, takes us too far ahead. For the moment we are still in Pozsony in 1899. His mother wanted Bartók to continue his musical studies in Vienna, not far from Pozsony. But Dohnányi studied at the Royal Academy of Music in Budapest, and following his example and advice, Bartók finally settled on Budapest.

In January 1899, Bartók played for the former Liszt pupil, István Thomán, a professor at the Academy. Thomán was so impressed that the gates of the Academy were flung wide open to him.

L’ÉDUCATION SENTIMENTALE

In the fall of 1899, when Bartók was eighteen, he moved to Budapest to study the piano with István Thomán and composition with Hans Koessler at the Academy of Music. He lived in various rented rooms, missing the maternal care whose unbroken presence he had gotten used to in the past eighteen years, but was richly rewarded by the feeling which he dared not admit, even to himself, that for the first time in his life he was free and independent of his beloved mother’s overly assertive presence.

He rubbed elbows with society; he was afforded a glimpse of the homes and lives of educated, well-to-do bourgeois families with an interest in culture and the arts. He attended concerts, the opera and exhibitions, and in an attempt to enrich his limited rural culture, he did a great deal of reading.

However, just as it seemed that Bartók’s life was on track, illness once again attempted to silence him or, at the very least, divert him from the main path of his life. Two decades later, his mother recalled October 1899 as follows for the benefit of her grandson:

‘He [your father] had bronchial catarrh which—considering his earlier problem—appeared dangerous; I called a professor to him who, after he examined him, said he should give up his musical career; he should be a lawyer, for instance. Your father hadn’t cried in a long time, but then the tears rolled down his cheeks and he said he’d never be a lawyer, that was not the kind of life he wanted. Professor Thomán talked to Dr Ángyán and explained to him that for this young man music was like water to a fish; he’d be unhappy with any other career; music for him was the essential condition of life.’

With careful nursing and a change of climate Bartók was cured, and he was able to work for the rest of the school year without further delays. His renewed health, however, was only temporary; while he was vacationing in Styria, he was suddenly taken ill, and mother and son had to remain there for weeks until his health allowed him to travel.

After a month of their unwelcome extended vacation, mother and son returned to Pozsony.

‘As soon as we returned, I had our family physician (Dr Vámossy) examine him, who left with a very grave expression on his face; I went over to him to speak to him privately, and he had the staggering verdict that there was nothing to do; wherever I might take the convalescent, his life could not be saved.’ The specialist who was called in for a consultation, the enthusiastic music fan Dr Pávay Vajna, chief physician at the hospital in Pozsony, fought adamantly for his life and prescribed a cure in a health resort in the mountains. Coming up with the expense and finding a way of taking off from work in the middle of the school year was no ordinary challenge for the widowed teacher. They had to stay in Meran, in South Tyrol, from November 1900 to April 1901, where Bartók gradually recovered his health and was able to continue his studies at the Academy. For the rest of his studies, his health seemed to hold out.

However, Bartók had other problems at the Academy with respect to his development as a composer.

Koessler seemed to be the ideal teacher for him only as long as they were focusing on technique, which basically meant emulating old masters. But when Bartók began his forays into other modes of composition, Koessler, who was convinced that everything had to begin with the basics, tried to hold him back. In retrospect, this was not a sign of ill will on his part, but pedagogical tact. The real difficulty, he felt, was that the young man, not being satisfied with the more or less apt re-creation of what others had created before him, wanted to take a different stylistic path. The hitch was that he did not know what direction to take. He did not yet understand the significance of Liszt’s innovations, he was no longer attracted to Brahms, and he had nothing to say in Wagner’s vernacular. He had not yet found his own voice. He had no choice but to keep quiet for a while.

In 1902, Bartók was still vehemently denying the connection between life with its accruing experience and the act of creation. In the fall of that year, Bartók played the draft version of his new E-flat major symphony for Koessler, who said: “The adagio must contain love, and there is no mention of love in this movement. And that’s a mistake. But one of the drawbacks of modern composition is that it can’t produce adagios.’

The symphony was fated to be one of Bartók’s aborted compositions. But a year later he found, if you will, the form, the style and central thought in which and from which he could construct an authentic and, in its spirit, independent work.

He himself was aware of the importance of this significant change: ‘It was the time of a new national movement in Hungary,’ he wrote, ‘which also took hold of art and music. In music, too, the aim was to create something specifically Hungarian. When this movement reached me, it drew my attention to studying Hungarian folk music, or, to be more exact, what at the time was considered Hungarian folk music. Under these diverse influences, I composed in 1903 a symphonic poem entitled Kossuth.’

Kossuth was the perfect embodiment of the popular patriotic sentiments of the day, and in January 1904. it made its twenty-three-year-old composer an overnight celebrity, someone quoted on the stock market of Hungarian art.

Kossuth was both modern and traditional, both European and the effective expression of national ideas; all of the Hungarian press, including the conservative papers, lowered their banners in respect to him. That same year it was performed in England under Hans Richter’s baton, if with far less dramatic effect than at home.

In the score of Bartók’s life, the ‘melodic line of success’ was thus soon followed by the counterpoint of failure, a motif that accompanied him emotionally, at times outstripping the main theme with its persistence. The pseudo-success of Kossuth in Manchester was itself an indication of this.

The failure was even more apparent when Bartók tried to authenticate his strivings as a composer and pianist by entering the 1905 Anton Rubinstein competition in Paris.

Seen with the eyes of the Hungarian musician, the result was dismal: Wilhelm Backhaus won the piano competition, while the prize for composition was not awarded. Yet the outward lack of success did nothing to diminish the unarguable signs of inner development. Bartók spent nearly two months in Paris and came into contact with the cultural life of the French capital, which far surpassed anything Pozsony, Budapest, Vienna and Berlin had to offer.

He discovered not only the museums and parks, the big squares and avenues, but the Paris of the dance halls and cabarets as well—the city’s frivolous freedom and spirit that did not shy away even from the fashionable fascination with death.

Perhaps this is where he received the initial impulses he needed to write The Miraculous Mandarin at a later date. But at the time it was not the enrichment of his spirit or intellect that impressed him the most, but rather the despondency and the solitude he felt, with only a faint glimmer of hope to tame a hostile fate. “I may have friends in Budapest…yet there are times when I suddenly become aware of the fact that I am absolutely alone!’

Another sudden change occurred in his life in 1905 when he left behind the Hungarian verbunkos style and with it the nineteenth century, and embarked on a search for another source, one better suited to finding something substantial in its depths.

And then, at the most opportune moment,

he happened upon Hungarian folk music and met his one and only true friend and the only ally worthy of him—Zoltán Kodály.

Yet the search for folk songs was not really an unexpected change of path in his career; after all, even when he wrote Kossuth and his Suite No. 1 he was looking for raw material, a musical mother tongue, a collective conceptual background.

Bartók met Zoltán Kodály, who had also attended the Music Academy, but with whom he was not acquainted back then, in the spring of 1905 in Mrs Henrik Gruber’s regular salon. A member of the bourgeoisie, Mrs Gruber was not only quick-witted and highly cultured, she also spoke several languages, was an accomplished piano player and a talented composer—an exceptional woman whom Kodály was to marry in 1910.

The first subject the two young men shared was folk music, which initially interested Bartók because of his nationalistic aspirations, and Kodály because of his academic aspirations. Of the two, Kodály, who was a year and a half younger and a college graduate, was nevertheless the more educated and more mature individual, and in him Bartók found a fine ally, a perceptive critic and advisor.

Kodály familiarized Bartók with the technique of collecting folk songs with the help of a phonograph as well as the most up-to-date method of classifying the collected material at their disposal then. Kodály, however, did not have much to explain; Bartók, who in his childhood was a passionate collector of insects, plants and minerals, had no problem incorporating folksong into his extant circle of natural phenomena. The two musicians divided the country—then still Greater Hungary—between themselves, from time to time comparing their separately collected material.

This soon opened the way to their major endeavour of national significance—collecting and publishing the full corpus of Hungarian folk songs.

As a first step, they published Magyar népdalok (Hungarian Folksongs), twenty folk songs set to their own untraditional harmonies for voice and piano, which they published in December 1906. The foreword, which was in the nature of a call to arms, was written by Kodály in both their names. In it, he wrote that their aim was no less than the transformation of domestic musical life into Hungarian musical life. ‘The vast majority of Hungarian society is not yet Hungarian enough and is no longer naïve enough and is not cultured enough for these songs to find a place in its heart. Hungarian folksongs in the concert halls!’

The thin volume attracted little attention at the time, and it took thirty years for its 1,500 copies to sell. Little did people realize that it signalled the birth of the new Hungarian music movement of the twentieth century.

In early 1907 Bartók, who was 26 at the time, received a teaching appointment at the Music Academy, which meant that his expeditions collecting folk music had to be restricted to the winter and summer recesses. For a while Kodály too was busy with other things: with his friend, writer Béla Balázs, he left for a six-month study tour of Berlin and Paris. The most important discovery of his trip was the music of Debussy—his masterpieces as well as his technique. Debussy’s novel conception of melody, the freedom of his rhythm, his new harmonic progressions inspired and liberated Kodály, and with his mediation, his friend Bartók as well.

The two major events of 1907 in Bartók’s life were the discovery of the ancient, pentatonic stratum of Hungarian folksongs and an unrequited love, which caused a great turmoil in his soul. The new discovery was made while he was collecting folk music in Csík County; the object of his heart’s desire was the beautiful and talented violinist, Stefi Geyer. Bartók wrote heated letters to the young girl in which he explicated Nietzsche’s teachings along with the tenants of his own naïve materialism. These letters contained everything; the thing they did not contain were Nietzsche’s third-party attitude, his ability to rise above things, and his sublime indifference.

Love brought a dramatic transformation in Bartók’s soul, revealing until then unsuspected depths that had been lying dormant in it. Wagner’s name and his music drama Tristan and Isolde with its lyrical handling of love and death are repeatedly mentioned in these letters.

The major preoccupation or rather thematic excuse of these letters was a concerto that Bartók was composing for Stefi. Originally, it would have been made up of the traditional three movements: ‘The idealized musical image of St. G. [Stefi Geyer] is ready—it is heavenly, intimate; and the untamed image of St. G., too is ready—this one humorous, playful and entertaining. Next I should prepare the picture of the indifferent, cold, silent St. G. But that would make for unpleasant music.’ Then one fine day the plan changes.

‘One day this week, as if on inspiration from above, I suddenly realized the inevitable, that your piece must contain just two movements. Two diametrically opposed images – that’ll be all. I’m just surprised that I didn’t see this undeniable truth before.’ These lines reflect not only Bartók’s discovery of the two-movement form as the modern vehicle for presenting and uniting two musical antitheses.

By the time the concerto was completed, the relationship, which never really got off the ground, was over once and for all. Instead of attracting the young girl of traditional upbringing who was standing on the threshold of a highly promising musical career that demanded full concentration on her part, Bartók’s incendiary thoughts and exalted emotions put her off.

In the end, work helped Bartók recover from his emotional crisis. He wrote his String Quartet No. 1, which was, basically, the continuation of his discarded Violin Concerto. Undoubtedly, the First String Quartet is the work of an artist who has been to hell and back, a return from the shores of death into life, into the community of men symbolized by the folksong. Kodály, who was familiar with the inner world of the piece as well as its biographical background called it, with reference to Berlioz, a ‘retour à la vie’.

Bartók himself was well aware of the significance of his String Quartet. In a letter dated 4 February 1909—a week after he completed it—he wrote the following to one of his students:

‘I firmly believe and avow that all true art manifests itself under the influence of impressions we gather from the outside world…Until I experienced it myself I did not believe that a person’s works speak of the important events and guiding passions of his life with more clarity than a biography. Naturally, we are talking about real and true artists.’

The letter was addressed to Márta Ziegler, the blonde, slender daughter of General Károly F. Ziegler, chief inspector of the Hungarian Royal Gendarmerie. At the time, Márta was Bartók’s pupil. They were married on 16 November 1909, after Márta turned sixteen. Their son Béla was born in August 1910.

THE TOWER OF SILENCE

Duke Bluebeard’s Castle, which Bartók composed to the libretto of the poet Béla Balázs, a friend of both Bartók and Kodály, was completed in 1911, but for many long years it remained the symbol of the moral triumph of its creator. Bartók entered it in a competition advertized by the Lipótváros Casino, one of Budapest’s cultural centres, where it was rejected as ‘unfit for production’. Since István Kerner, the respected conductor of the Opera House, was also a member of the jury, Bartók could not very well hope for an Opera premiere. Consequently, for years Duke Bluebeard’s Castle laid dormant in a drawer of his desk.

In the same year. a number of Hungarian composers with Pongrác Kacsóh, the nationally renowned composer of the romantic musical play János vitéz among them, founded the New Hungarian Music Society (UMZE). Kacsóh, who was president of the society, championed Bartók from the first moment he appeared in musical life. Their aim was to form a professional orchestra devoted to the new music. Bartók as well as Kodály participated in the preliminary planning. However, due to the lack of the requisite moral and financial backing, their plans were frustrated, with the periodically re-emerging Society giving sporadic chamber music recitals. In 1912 this series of disappointments led Bartók to withdraw from public musical life altogether.

He had been living for a year in Rákoskeresztúr by then, a garden suburb of Budapest an hour’s ride by train. Bartók did not give concerts and did not look up publishers or the Philharmonic Society with new works; his teaching at the Music Academy was his only tie to musical life. On the other hand, basically at the last moment before the outbreak of the First World War, his folk music collecting took him to Africa, where he collected Arab folk music in the settlements around Biskra, which were as yet untouched by civilization. The effect of this trip would later manifest itself in several of Bartók’s works.

With the outbreak of the war, the failures of the recent years paralysed Bartók. This paralysis was relieved somewhat in 1915, when he began to compose once again and at the same time he turned his attention to contextual and formal questions of organising folksongs into art music cycles.

Bartók wrote two masterpieces during the war years—his String Quartet No. 2, in the slow movement of which he mourned Debussy by conjuring up a motif from his Pelléas et Mélisande, and The Wooden Prince, a ballet composed to a scenario by Béla Balázs.

It was thanks to Balázs’s efforts that the ballet was performed on the stage of the Opera House with a stunning scenic design by the Intendant, Count Miklós Bánffy. The performance was directed by Balázs—who for the first time tried his hand at directing—and it was conducted by the thorough and conscientious Italian conductor, Egisto Tango. The press was geared for a scandalous failure. Balázs described the premiere atmosphere of 12 May 1917 as follows: ‘The ticket prices were raised steeply. They were preparing for a huge Opera scandal. Reviews were written beforehand to the effect, “For Christ’s sake, Béla, stop composing!”’

And it was a memorable evening. After the last note of the music had died away, there was total silence. No clapping. No hisses and catcalls either. It seemed for a while as if an invisible scale of gigantic proportions were being tipped this way and that. In the deadly hush of the auditorium, a silent battle, like some inner struggle. Then the ecstatic applause from the gallery shattered the silence and swept down to the boxes and the stalls like an avalanche, sweeping the rabble of the press with it. Many reviews had to be rewritten that night.

On 24 May 1918, one year after the premiere of The Wooden Prince, Bartók’s opera, Duke Bluebeard’s Castle, was finally performed seven years after it was composed.

Events around Bartók speeded up. Europe’s terrible danse macabre was approaching closer and closer to him, trying with all its might to lasso him into the group of its ‘attendant dancers’. The Spanish flu epidemic, to which millions fell victim throughout Europe, caught up with him as well, attacking his hearing. When Kodály accompanied a physician to Rákoskeresztúr, Bartók asked him to act as guardian to his eight-year-old son, should it come to that. A month later, however, Bartók regained his health and as the ‘answe’” to his ordeal, he wrote his own danse macabre, the pantomime-grotesque The Miraculous Mandarin after the libretto by Menyhért Lengyel.

In 1919, during the short-lived dictatorial Hungarian Republic of Councils, also known as the Hungarian Soviet Republic, Bartók was a member of the Music Directorate along with Dohnányi and Kodály. Although he had many good and noble plans for reform, he soon fell out of favour with the so-called restoration (the reinstatement of the monarchy) to follow. Because his stage works were based on scenarios by the ‘émigré Communist’ Béla Balázs, who was forced to flee, they were taken off the programme of the Opera House.

His income, too, was gone with the wind. In a letter to Menyhért Lengyel dated 10 January 1920, he wrote: ‘We live in great misery; true, there are no material shortages now, but whatever is available is unaffordable for poor people like us. As a result, I spend the whole winter with my family in one room, in our smallest, where I cannot even work on orchestration…My income is hardly enough to meet the only luxury we have, not going hungry.’

IN EUROPE ONCE AGAIN

In the early 1910s, Bartók did not enter the tower of his own accord, he was forced into it, and the war years, the Hungarian Republic of Councils and the counter-revolution increased his isolation tenfold.

The moment the borders were reopened in early 1920, he applied for a passport and headed for Berlin, where he gave his first post-war European concert. He was involved in discussions with Max Reinhardt’s theatre company about a possible commission, but nothing came of it. He could not very well count on a teaching appointment, much less on making a living as a music ethnographer. After nearly three months, he returned to Budapest.

On his return, Bartók decided to leave the suburbs, and accepted an invitation from the banker and art lover József Lukács, the father of philosopher György Lukács, to live in his villa, where Bartók and his family spent two years. The newly defined national borders made folksong collecting more difficult; on the other hand, Bartók the ethnomusicologist had no need of enhancing the material he had amassed over a decade and a half. The new circumstances prompted him to write his first large-scale comprehensive study, The Hungarian Folk Song. This too was written in the Lukács villa, along with the piano cycle entitled Improvisations on Hungarian Peasant Songs and his Sonata for Violin and Piano No. 1. Both were born after years of creative silence.

In his Sonata for Violin and Piano No. 1 (1921), and in his Sonata No. 2, written a year later, Bartók had approached Arnold Schönberg’s expressionism without, however, deserting his own musical conceptions. Bartók wrote the two works for Jelly d’Arányi, the Budapest-born violinist who settled in London; his lyrical self-revelation was addressed to her sensitivity as woman and artist.

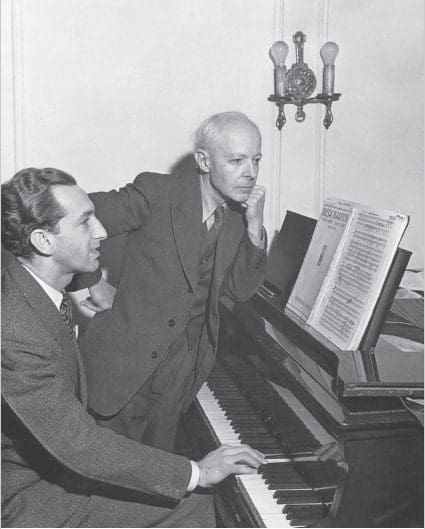

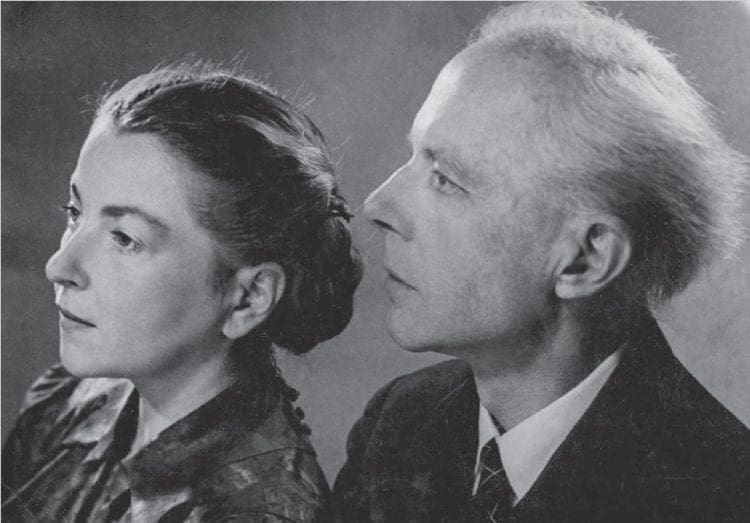

His family life was transformed all the same; in the summer of 1923 he divorced Márta Ziegler and a couple of weeks later married one of his piano pupils, Ditta Pásztory, twenty-two years his junior, who from 1938 would become his partner in their two-piano recitals. A year later Ditta gave birth to their son, Péter.

As a composer, he distanced himself from Schönberg’s music and drew closer to Stravinsky whose novel, ostinato-based development, the rousing effect of the frequent repetition of brief rhythmic and melodic figures attracted him. He was fascinated by the neo-barbaric blocs of the Russian master’s scoring for large orchestras as well as the surprising chamber music effects of his orchestration for small orchestras with their novel soloist effects. Meanwhile, both as a theme and as a model of organic development, nature also came to play a more and more important role in Bartók’s works.

In 1923, a commission for the celebration of the 50th anniversary of the unification of Pest and Buda offered Bartók a chance to experiment. He paraded a string of themes inspired by the folk music of various peoples (Hungarian, Romanian, Arabic. and Slovak) but composed by himself, creating a unified musical vernacular from them, until in the final section of the piece, he united them formally as well; while preserving their independence, he gave them a unity of a higher order, an achievement that except for his artistic vision, no politician or politicians have been able to emulate.

The Dance Suite—this was the title of the new piece—did not make much of an impression at its 1923 premiere in Budapest, but it was greeted with accolades two years later in Prague at the International Festival of Contemporary Music, and during the following two seasons, it was performed nearly 70 times in the concert halls of Europe and America.

This triumph—as is only to be expected in Bartók’s career—was soon followed by disappointment. In late 1924 he finished orchestrating The Miraculous Mandarin, hoping that the premiere would be held either at the Budapest Opera or at one of the large German theatres. However, citing ‘moral’ considerations the management of the Opera refused to stage it (and would stick by its decision for another twenty years), so after weighing their options, Bartók and his publisher decided on Cologne, where Eugen Szenkár, the music director of Hungarian origin, championed the cause of the Mandarin.

The premiere, however, was a fiasco.

According to music critic Hermann Unger’s account, ‘Cologne, the city of churches, monasteries and chapels whose praises Heinrich Heine had sung, has experienced its first truly big opera scandal; the long minutes of hissing, booing, whistling, drumming, hooting that did not hold itself back in the presence of the composer and which after the fire curtain came down, when the composer and the conductor appeared in front of the small door escalated into yelling.‘

In short, then and there, the piece was a failure. What is more, the Cologne debacle continued to influence the European production of the Mandarin for decades, and Bartók was never again to see it on stage.

On the other hand, the fiasco could not tarnish his reputation.

He had won acknowledgement not only as one of the leading lights of the new music, but also as an exceptional pianist. The manner in which he composed remained hidden from audiences and even those closest to him. But the energies that were released when Bartók played the piano in public could be witnessed and experienced by thousands.

1926, the year of the fiasco of his Miraculous Mandarin, was also the year of new works for the piano in Bartók’s life. It was the year of his Sonata, the Out of Doors cycle, the Nine Little Piano Pieces, the Piano Concerto No. 1 and, finally, the Three Rondos on Folk Tunes completed in 1927. A whole slew of exciting experiments are summarized in these works—the tensions, the intensification of extremes, the excitement of the interplay of symmetry and asymmetry, the appearance of baroque forms and means of expression, the maximal use of the melodic and percussion functions of the piano, and the appearance of various ways in which folk music can be turned into art music.

The great slow movements of the ’30s (Music for Strings, Iercussion and Celesta, 1936; Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion, 1937; Divertimento, 1939) no longer concern themselves with the voices of nature that are welcoming despite its severity, but the danger signals of the approaching catastrophe—dread and raw fear—the voice of mourning. ‘Europe, watch out!’ shrills Bartók’s music. Death, which has been lying in wait for him since his youthful years, now seems to want to fence in and annihilate an entire continent, along with its culture. Is there escape from its clutches? And if so, where and how?

Bartók, who had earlier answered the challenges posed by the world around him either with stubborn silence or outrage sublimated through music, now found himself increasingly given to protest in writing. In 1931, when Italian fascists assaulted the great conductor Arturo Toscanini, who refused to conduct their anthem, the Giovinezza, Bartók drafted a declaration ;for the protection of artistic freedom’. After Hitler came to power, he refused to give concerts in National Socialist Germany. Along with progressive-thinking musicians, writers, artists, scientists and politicians—Kodály, Zsigmond Móricz, István Csók, among others—in 1938, he protested in the newspaper Pesti Napló against the so-called Jewish law, a resolution that was meant to institutionalize discrimination and was about to be enacted by Parliament.

The same year, when the German Reich annexed Austria, Bartók wrote a letter to Annie Müller-Widmann, a close friend and confidante in Switzerland, in which he prophesied ‘the imminent danger that Hungary will also surrender to this regime of thieves and murderers; the only question is when and how?…I would feel it my bounden duty to emigrate while it is still possible.’

EVENING IN AMERICA

To traverse the ocean aflame with wartime, heading from the certain intolerable into the intolerable uncertain—this put an enormous emotional burden on the composer, whose body had embedded in it a highly sensitive radar system that responded to the perils of the age. But as if that were not enough, Fate, his steadfast adversary which attacked him either in the form of illness or tried some other means to deter him from the main path of his life, now placed yet another roadblock in his way, designed especially for him and his wife. In the midst of the war-time confusion, their luggage, which contained the most important objects needed for their survival in America (manuscripts, research material, concert clothes), was seized at the French and Spanish border. The Bartóks had to board the ship without them, and when they reached America, they got off the boat with nothing but their hand luggage. Luckily, four months later, when they had given up all hope of ever seeing them again, their belongings arrived safe and sound.

But the temporary loss of their belongings was not the only reason why Bartók could not continue his European way of life on the other side of the Atlantic smoothly. Though his physical safety was ensured in America and he did not have to fear the spread of ‘pernicious ideologies’, this world was not his world—he was no longer a guest, but he did not feel at home either—and never would. In Europe he was Someone, with a capital S, who had to shield himself against annoying public attention; in America, he received no public attention at all. With the exception of some good friends and loyal admirers, no one even noticed he was there.

On the other hand, it is true that America was swamped by European refugees in those years. No wonder if the public did not turn its attention to a man like Bartók, who was so humble in his ways, who had a horror of the limelight except when it came to music, and who never demanded anything for himself.

Apart from a small and select circle of music lovers, the American public was probably not prepared in any case to hear and appreciate the Bartóks’ music. Consequently, their recitals for duo piano drowned in the ocean of musical offerings and were hardly ever followed by further performance requests, which at first dwindled in number, then ceased altogether. Their last appearance together was in January 1943, when they held the American premiere of the Concerto for Two Pianos, Percussion and Orchestra in New York City, New York with Fritz Reiner conducting.

Still, they did not live in privation, at least not in the physical sense. Bartók’s publisher, the London-based Boosey & Hawkes, opened a concert agency in their New York branch office expressly to manage the composer’s affairs. Despite the wartime difficulties, they continued publishing Bartók’s manuscripts, which involved sending them back and forth between the United States and England for proofing, and they regularly gave him advances on his royalties. Furthermore, Columbia University, which in November 1940 had conferred an honorary doctorate on Bartók, entrusted him with transcribing Serbo-Croatian folk music recordings and editing them for eventual publication. The appointment, which began in May 1941 and lasted until 1943, provided Bartók with a humble but secure source of income, which for him was of utmost importance at the time.

Since the 1920s, Bartók had been writing most of his major works on commission, but during his first years in America, he was not flooded with offers. Nonetheless, he flatly refused to teach composition, whereas he had plenty of opportunity to do so; with one or two rare exceptions, he never accepted such requests in his entire life. He said time and again that

in his opinion, composition cannot be taught,

and he would not have afforded a glimpse into his composition ‘workshop’ in his wildest dreams. He would have been willing to teach the piano, but no institutions asked him, while his private piano teaching was sporadic. The famous orchestras did not include his works in their programmes, and Bartók felt that his career was grinding to a halt. ‘My career as a composer is at an end’, he wrote to his former student, Wilhelmine Creel on New Year’s Eve 1942.

Also, the illness that for a while had allowed him breathing space attacked him when he was least able to resist it. Initially he felt pain in his arm and shoulder, which after a while incapacitated him, and he could no longer give concerts; then he suffered from mysterious bouts of fever which came at regular intervals and gave him cause for concern. His doctors could not agree on the diagnosis; one explanation seemed to be the recurrence of the lung disease he had suffered from in his youth. All this added not only to his other worries, but to his expenses as well, and by early 1943, it seemed that there was no return to normalcy.

Yet, just as Bartók hit rock bottom, aid came from a source and in a guise he could accept. Thanks to the unrelenting efforts of his admirer Ernő Balogh, the ASCAP (American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers), of which Bartók was not a member, agreed to cover the cost of his hospital care and his sanatorium bills.

Bartók was in hospital once again when the violinist Joseph Szigeti turned to Serge Koussevitzky, the respected conductor of the Boston Symphony, on Bartók’s behalf. Their long conversation at Bartók’s hospital bed resulted in Koussevitzky commissioning Bartók to write an orchestral work in memory of his departed wife.

The composer, who had not written so much as a single note of a new composition since he completed his String Quartet No. 6 in Budapest, was elated, and his health took a dramatic turn for the better. In just fifty-five days during the summer and early fall of 1943, he finished his Concerto for Orchestra in five movements.

The Boston premiere of the Concerto in December 1944 and its first performance in New York soon after were a veritable triumphal march for the composer, the first of its kind for him since he left Hungary. Commissions came pouring in. Yehudi Menuhin asked him for—and was given—a Sonata for Solo Violin; the Scottish viola player William Primrose ordered a Viola Concerto which, however, Bartók could not finish; and Ralph Hawkes, his publisher, commissioned a seventh string quartet of which only ideas for themes remain.

Bartók spent the summer of 1945 at Saranac Lake resort in New York State. He and his wife Ditta, who was in frail health herself, lived in a small guesthouse under the simplest of conditions, though neither cared. Bartók felt that his physical strength had returned and even undertook walks and short excursions. He also began work on new compositions. A finished piece, the manuscript of which he had hidden under the half-finished Viola Concerto, was meant as a surprise for his wife’s birthday in October. Its title: Piano Concerto No. 3.

The war came to an end; leaving Europe in ruins. Bartók would have liked to return to Hungary ‘for good’, but he knew that circumstances would not yet allow it.

Apprehensive, he inquired after his relatives, friends and loved ones. He turned in writing to those of his American acquaintances he thought were well off, asking them to help the Hungarian people, who had suffered so much in the recent war. Meanwhile, he was working on his piano concerto. Their son Péter, who had come to the United States in 1942 and who was discharged from the Navy in August 1945, went to join his parents at Saranac Lake. Life seemed idyllic—the weather, Bartók’s progress with his music, and his recovery. Little did they know that this was the respite before illness launched its final assault on Bartók’s weakened physique.

In late August, Bartók felt ill and they hurried back to New York. He became bedridden, but continued to work on the score of his Piano Concerto No. 3. Though the people around him remained hopeful, he knew that the end was near, and that his pen was running a desperate race against death.

In the second half of September, around the 20th of the month, his physician sends him to the hospital. Bartók asks for a single extra day, saying he had something important to take care of first. Had he been given that extra day, he might have been able to finish scoring the Piano Concerto. As it is, however, he could only write the piano part into the last seventeen bars. Still, he completed the draft, and after the last note, just like after the unfinished last bars of the full score, he wrote—atypically—THE END.

At the time no one knew that this end was in fact the BEGINNING, that when all is said and done, in the life-and-death struggle Bartók waged all his life, the triumph over the demon was HIS.

Click here and here to read the original articles.

Related articles: