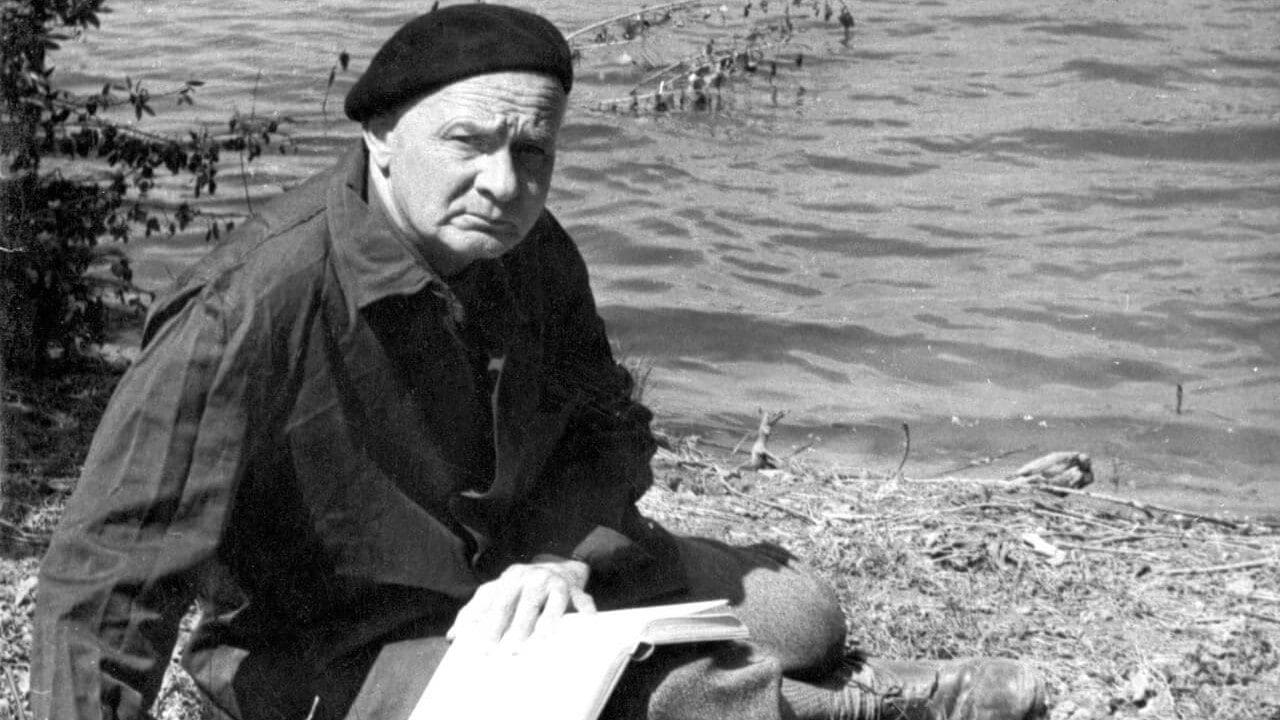

Béla Hamvas (1897–1968) was one of the most outstanding Hungarian thinkers of the twentieth century, whose enormous (and to this day not fully published) oeuvre represents some of the most important work of philosophical disposition ever written in the Hungarian language. An author of essays, studies, and novels, Hamvas possessed a vast scope of erudition that was truly universal in all possible senses of the word. Beyond the exponents of modern and premodern philosophy proper, he was deeply interested in theology (not just that of Christianity but especially of Hinduism), mythology (Buddhist and other mythologies in addition to Greek and Roman), the history of religion, psychology, theoretical physics, sociology, social theory, historical science, and mathematics. Given that the critique of modernity constitutes a cardinal point of his oeuvre, we must regard Béla Hamvas as having has more than just a passing interest in conservative thought.

One of the twentieth century’s most fascinating thinkers writing in Hungarian, Hamvas is ‘now without a doubt part of the canon’,[1] even if he has not yet gained full admission to the pantheon of Hungarian philosophy. He remains, to quote Péter Balassa, very much ‘outside the guild’[2] of the discipline, notwithstanding the string of studies and monographs published on his work by the early 2020s.[3]

What makes Hamvas truly unusual and distinctive as a maverick thinker is

the deliberation with which he attempts to defy the science-driven mindset of modernity,

which he calls ‘scientism’, combined with his ability to articulate the terms of this defiance on the most sophisticated level. Interestingly, Hamvas’ radical critique of science fell on deaf ears even among such contemporaries as Dezső Szabó or the ‘thinker-novelist’ László Németh, whose thought happened to share a number of traits with that of Hamvas. In many ways, then, Hamvas found himself outside the ‘society of thinkers’, even as he created a major oeuvre of philosophy with important implications for the theory and philosophy of society.

An author of essays, studies, and novels, Hamvas possessed a vast scope of erudition that was truly universal in all possible senses of the word. Beyond the exponents of modern and premodern philosophy proper, he was deeply interested in theology (not just that of Christianity but especially of Hinduism), mythology (Buddhist and other mythologies in addition to Greek and Roman), the history of religion, psychology, theoretical physics, sociology, social theory, historical science, and mathematics. Given that the critique of modernity constitutes a cardinal point of his oeuvre, we must regard Béla Hamvas as being more than just a passing interest for conservative thought.

Hamvas was committed to the synoptic view of the sciences and cultural phenomena from an early age. His ‘universal orientation’ was of a philosophical nature, insofar as the concept of philosophy with an expanded meaning in terms of time and semantics could be the one that best reflects Hamvas' specific view. Undoubtedly, his novels have a philosophical approach, just like his essays, glosses of his studies, and aphoristic comments. His perspective is primarily philosophical—and not literary or scientific in the rationalist sense of the word, even when he talks about natural science and even when he talks about world literature, the theory of the novel, or the history of religion. However, if we examine the relationship between Hamvas and philosophy in the closest, most concrete sense, we can say that

Hamvas very closely followed, observed and constantly read the philosophical developments of his own time.

He reflected on them and held a special dialogue with the representatives he considered most important.

What Hamvas considers his primary object is the investigation of the fundamental questions of philosophy, focusing his inquiry on the core issues and principles of metaphysics, dismissed as ‘pointless questions’ by certain positivist thinkers, such as Rudolf Carnap. Thus, he is first and foremost interested in the true nature of things like God, consciousness, life, death, immortality, soul, and spirit. And the basic condition for this is the courage to ask again and again primal questions that are considered closed by dogmatic views.[4] This is the archaic, or at least the pre-modern philosophical quality—not in the sense of primitiveness or the so-called ‘prelogical thinking’—that Hamvas consciously tried to represent.[5] This is also reflected in Hamvas' philosophical approach, which, in addition to the focus on the ‘whole’ and the intense interest in the sciences, reached the point of explicit and even sharp criticism of modern science. Not by chance, since it is modern—that is, materialist, atheistic, reductionist and downright anti-spiritual science in Hamvas' interpretation. His criticism of science is also behind Hamvas' efforts to put metaphysics, which in the eyes of the main line of modern science and its most significant representatives—either in the sense of outright denial or simple neglect—is considered to be beyond the focus of the investigation.

Hamvas noticed early on that the triumphant science of the 19th century, which considered religion and metaphysics to be ultimately ‘belonging to humanity's childhood’ or simply banished it to the world of superstition, was increasingly venturing into the area formulated by the logical positivists as ‘metaphysical judgments’, that is, he himself begins to formulate propositions about the meaning of life. Hamvas therefore perceived the hidden religious, dogmatic and ideological nature of certain trends in modern science. He also observed the fact that modern science produces a (naïve) explanation of the world, which can actually be translated into the propositions of materialism in the philosophical sense, often without the scientists even knowing what philosophical materialism is. The philosophers mentioned by Hamvas as the greatest, such as Nietzsche, Schopenhauer, Bergson, Heidegger or Klages, all—albeit in different senses and degrees—were critical of the natural sciences, especially the absolutization of scientific rationality, and their influence can also be seen from the fact that how Hamvas, at a meeting of the Hungarian Philosophical Society, formulated his view on the specific tasks and nature of philosophy:

‘In today's philosophy, nothing is as essential as form...Many people say we are not strong enough to create systems. It's a shame to make such statements. Fifty years ago, the believer of the theory of progress would have thought to have discovered an achievement in this phenomenon as well; today the believer of the dying culture judges it as a sign of agony...Modern philosophy does not like the system...Modern philosophy is essay-like...An essay is an experiment. In other words: trying. Actually a comment…a short, clear, simple, direct, well-written comment against the cumbersome and messy, abstract and hardly followable systems thinking...a hundred well-written lines are more than a hundred poorly written pages.’[6]

Like Heidegger and Klages, Hamvas noticed early on—and much more keenly than most contemporary Hungarian intellectuals, for example László Németh,[7] who criticized Hamvas in relation to the criticism of science—that

science created a latent ideology.

This ideology, like religion in the pre-Enlightenment era becoming an all-pervasive presence, that seems to be a fair explanation of the world shared by the general consensus. It therefore seems to be something, which, even if it is not clearly realized by individuals living in the worldview of modern science, is the ‘standard of truth,’ the ‘absolute reality,’ which is ‘guaranteed’ by individual and collective experience. Hamvas stated in this regard in his article ‘Philosophy Today’ that

‘[…]philosophy is not a science. Science has no style, nor does it need one.’ And since, using the traditional Platonic categories, Hamvas characterized science with knowledge (episteme) and philosophy with knowledge (doxa), sharply opposing the ‘democratic’ idea of objectivity of modern natural science, when he declared: ‘Knowledge can only be personal.’[8]

Indeed, Hamvas believed—and this is reflected in his article Science–religion and Religion–science as well as in his several contributions at the meetings of the Society —that science, in addition to being built on a series of implicit logical and epistemological presuppositions, is just as much based on a latent metaphysics as other worldviews. However, the denial of subjectivity and the subject in the metaphysical sense presents the worldview of modern science for him in a falser light than ever before.[9]

‘Science is also a type of religion, especially if it comes up with the demand to provide answers to the problems that religion used to answer. Yet part of science does exactly that. If it says more than just material, it becomes a spirit and a life-transforming force. [...]The ‘factuality’" of science—the most uninteresting. It is not truer, only its preconditions are stricter: data, facts are the prejudices of science, the scientific method is a built-up system of prejudices.’[10]

He saw as that negations are implicit statements just as much as most statements contain one or more negations—at least according to the rules of ‘Aristotelian’ logic—and this logical paradigm is the one on which modern science has mostly thought and thinks.[11] At the same time, Péter Balassa rightly notes that Hamvas was not anti-science in general, he opposed materialist science, that is, the materialism of science, rather than science in general, and the openness his traceable in Hamvas to interpret certain trends and theories, expressed within modern natural science in a direction towards analogies of archaic metaphysics.[12]

Hamvas' focus on metaphysical questions in the field of philosophy did not simply stem from his belief in God or his religious predisposition, but rather from this critical attitude towards modern natural science, from a ‘scepticism against scepticism.’ It is this Socratic ‘wonder’ that opens the increasingly concrete horizon for Hamvas. In this, his scepticism towards a science, which primarily validates itself through the applications of technology, was already increasingly felt worldwide by the 1920s and 1930s—arising from the beginning of the technical transformation of education, modern culture, the press and the world, resulting a disillusionment and a need for a truer knowledge emerges.

Hamvas's true intention can also be grasped in this: he is not anti-science, but a man who loves science, but this science is Scientia Sacra,[13] a ‘sacred science’, and not materialism and ideology dressed in the garb of science, but a true philosophy, a knowledge that does not leave out the subjectum.

As András Lengyel notes, based on Hamvas' conduct as a philosopher, in the narrower sense, by his six speeches at the meetings of the Hungarian Philosophical Society, he seems to be a significant ‘thinker-writer’ who is receptive to the current problems of philosophy and its most prominent, leading representatives. As he writes:

‘Béla Hamvas's image of philosophy and his own philosophy behind it, which ultimately constitutes this image, is not an ordinary, scientific experiment; he stands almost alone in Hungarian philosophy before 1944. At the same time, this experiment is not without its peers in recent European philosophy. He belongs to the great line that starts with Kierkegaard and Nietzsche and culminates in the contemporary ‘existentialists’, above all in Jaspers—he is primarily related to them and in several points parallels Heidegger after the “turn”.’[14]

[1] András Lengyel, ‘‘‘… szólj Szókratész, van értelme még?” Hamvas Béla filozófia-képe’, Forrás, 37/10 (2005), 87.

[2] Péter Balassa, ‘Egy beszédmód körülírása – Hamvas Béla olvasásához’, in Lajos Ambrus (ed.), Krízis és karnevál (Budapest: Nap Kiadó, 2009), 74.

[3] See for example Anikó Kurucz, Hang, szó, személy. Hamvas Béla nyelvgondolkodásának filozófiai és poétikai aspektusai (Budapest: L’Harmattan, 2022).

[4] By the way, Heidegger, also rephrased the question in ‘why is there something rather than nothing?’ and called it ‘the fundamental question of metaphysics.’ (Martin Heidegger, Introduction to Metaphysics, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1959, 7-8.)

[5] Hamvas embraced the idea of Tradition in all likelihood from the second half of the 1930s.

[6] Béla Hamvas, Közös életrend (Budapest: Medio, 2019), 265.

[7] See László Németh's criticism of Hamvas: Aranykor és farkasfogak in Lajos Ambrus Lajos (ed.), Krízis és karnevál, 38-43.

[8] Béla Hamvas: Közös életrend, 265.

[9] Béla Hamvas, Krízis és katarzis (Budapest: Medio, 2019b), 119.

[10] Béla Hamvas, Krízis és katarzis, 119.

[11] ‘In the 19th century, natural sciences, the main thing was not what it discovered, what it proved, what it justified, but that it took a stand against eternal life, which was branded as superstition and declared that human life would become nothing, just as worms become nothing , cultures and celestial bodies.’ (Hamvas, Krízis és Katarzis, 119.) The excerpt is translated by the author.

[12] ‘The fact that the natural sciences still consider this Newtonian model, which has shrunk to a borderline case in natural science, to be scientific, is partly because they misunderstand themselves: their subject is not primarily nature; and partly because of the ignoring of the consequences of the modern physical worldview.’ According to Balassa, Hamvas' ‘view of reality’ can be compared to that of the great modern physicists (Einstein, Bohr, Heisenberg, Weizsäcker).’ (Balassa, ‘Egy beszédmód körülírása – Hamvas Béla olvasásához’, 77) The excerpt is translated by the author.

[13] Cp. one of Hamvas’ main works entitled Scientia Sacra.

[14] Lengyel, ‘‘‘… szólj Szókratész, van értelme még?” Hamvas Béla filozófia-képe’, 99.

Read more by the same author: