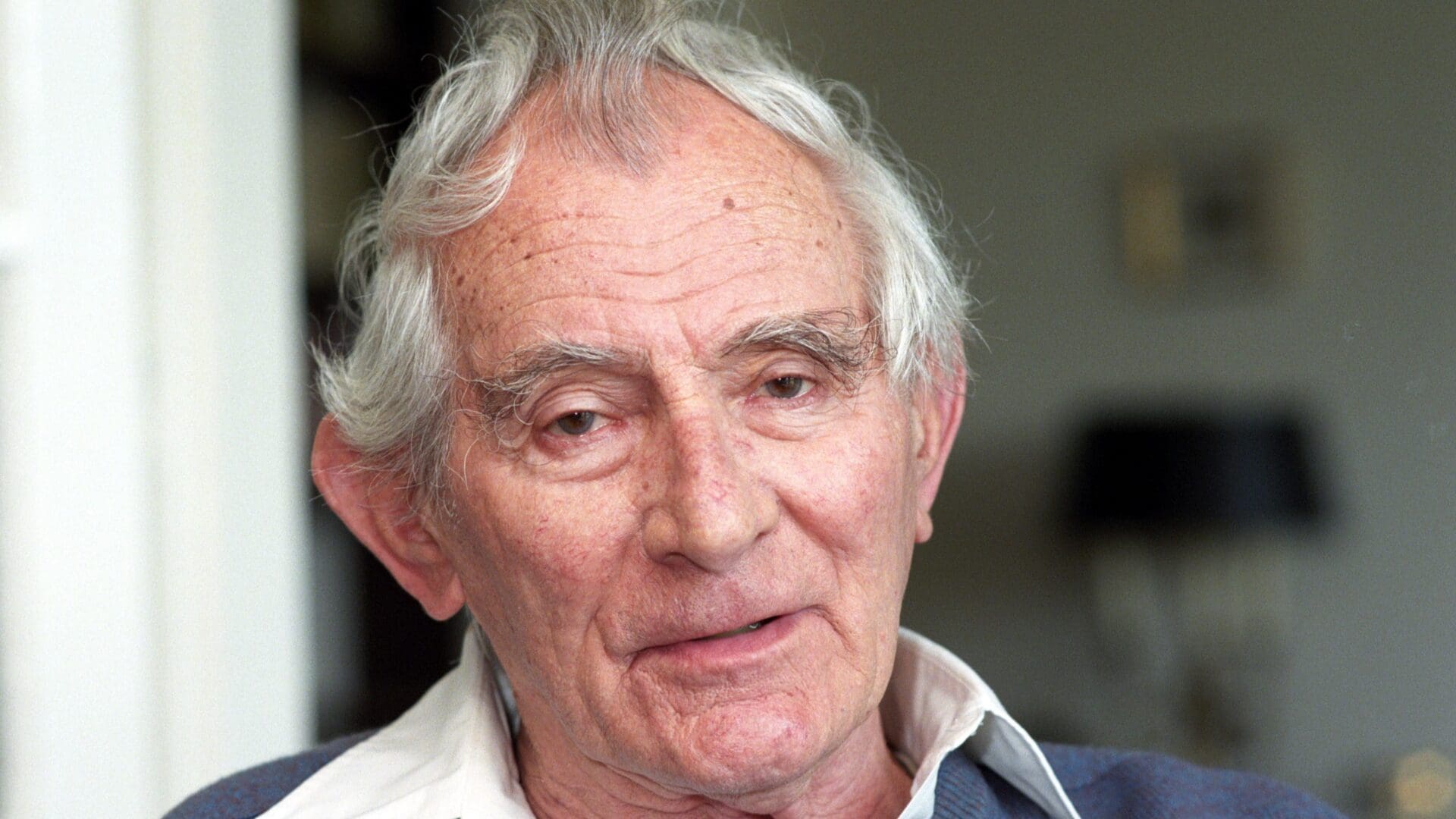

Gyula Gombos may be not well-known, but he was an important Hungarian writer and literary historian, born in 1913. He was a significant, but not popular author, whose most notable works were written in the realm of the history of ideas and literary criticism. (While their names sound alike, he should not be confused with the right wing PM of the early thirties, Gyula Gömbös).

In his memoirs, he described his simple childhood in Temesvár (today: Timisoara, Romania), in a somewhat impressionistic way: he wrote of his father’s moustache, his reserve, his mother’s home-made medicines, the pig slaughters and the games with the Jewish children next door. He also described the end of the First World War, the French occupation, the experience of humiliation. The family moved to Budapest in 1925, and from then on, he wrote, his father was not only taciturn but also bad-tempered.

Gombos graduated from the Calvinist School in Lónyay Street and then took up a teaching post. He wrote his first review of a sociography by Gyula Illyés, and then published theatre and film reviews. Later he worked as assistant editor of the Hungarian paper Magyar Élet (Hungarian Life), and from 1941 he edited it.

Magyar Élet was a journal of national politics, written by the right wing of the ‘popular’ or ‘populist’ (népi) writers—many of whom eventually made their compromises with the Communist left, such as Péter Veres, József Darvas and László Németh. In 1939 the paper was briefly banned because of an anti-German article by Dezső Szabó. The paper took a peculiar stance, which was not uncommon at the time: it published both anti-Semitic and anti-German articles. At the same time, it was rich in literature, criticism and art, preferably, of course, from the pens of the simple sons of the Hungarian people—it was giving precedence to this source of intellectual achievements that made the paper ‘populist’.

In August 1943, Gombos spoke at the so-called Szárszó Conference,

where he argued for the Hungarian ‘third way’, calling for a system that was neither capitalist, nor Communist.

He was very young at the time, only 30 years old—another indication of his decisive character. In this speech he also gave an accurate picture of the negative aspects of interwar Hungary, criticising it not from the left but from the ‘populist’ side. He gave an important and insightful overview of the collapse of historic Hungary, the revolution of ’18, the Soviet republic of ‘19, the impact of the Trianon peace treaty, social tensions and the limitations of Hungarian foreign policy. One of his important and still valid criticisms was that intellectuals, writers and leading politicians all speak a different language, and one of the main problems is that they do not talk to each other and do not ‘promise’ each other anything.

Although Gombos was an anti-German activist during the Second World War, he was arrested in 1947, convicted in a show trial and imprisoned. He was released in 1948, when he emigrated with his family first to Switzerland and then to the United States.

During the years of emigration, he worked for Radio Free Europe, and his work was strongly anti-communist.

While in emigration, he wrote a book about the suffering of Protestants under communism and about various Hungarian writers.

Of course, even during his years in the US, he was not blind to the state of the society around him, noticing with a sharp eye both the positives and the negatives. Among other sociography-like pieces, he for instance wrote an interesting essay on social mobility in the US. As well as appreciating that hard-working and clever people coming from humble backgrounds can get ahead in America, he also noted that the main ways of breaking into the top elite were by birthright, invitation or family connections and friends, especially from one’s alma mater. This critique of his would place him more in line with the contemporary left, although it has to be noted that his attitude was characteristically that of the Hungarian ‘populist’ right: combining economic progressivism with a national and Christian identity.

He was one of the youngest ‘populist’ writers, and perhaps unsurprisingly, unlike most ‘populist’ writers, he lived to see the fall of the Communist dictatorship. After the system change, he returned home and published mainly on Dezső Szabó and László Németh. He died in 2000 at the age of 87, and his work is still undeservedly understudied, both as a writer and a literary historian.

As one of his admirers quite aptly wrote of him: ‘His place in the hierarchy of “populist” thinkers and writers is not in the second, but in the first rank, in the company of those whose intellectual and creative achievements can be considered particularly valuable and significant.’

Related articles: