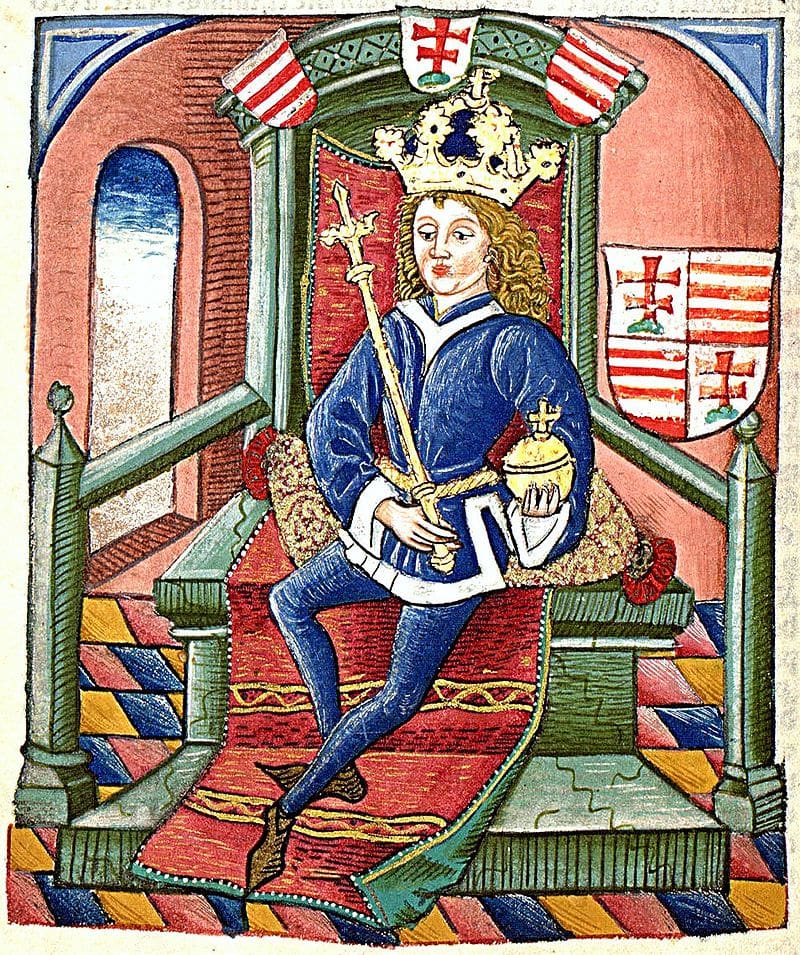

The Mariazell Basilica dedicated to the Virgin Mary is one of Austria’s most popular tourist attractions, and a national pilgrimage site. Its foundation dates back to the mid-12th century, yet the construction and re-foundation of the present church in the 1370s was due to a generous donation from King Louis the Great of Hungary (r. 1342–1382), for which the monks living there were not at all ungrateful.

A life-size statue of the King greets visitors at the church’s main entrance, and in the tympanum above the entrance, constructed around 1400, we can see his figure once again, offering the miraculous icon of the Virgin Mary. The same image, portrayed within a battle scene, was also depicted on a panel in the nearby St Lambert’s Abbey around 1430.[1]

No other king outside Hungary has received such an honour.

The story of the Mariazell tradition was recorded by Austrian chronicler and Benedictine monk Johannes Mannesdorfer in 1487, who wrote:

‘Louis, the invincible and most Christian King of the Hungarians, with twenty thousand horsemen and footmen, stood in the way of the Ottomans…In his dream, the glorious Virgin herself appeared to him, and placing her image on his breast, encouraged the King and commanded him: “Fight the enemy.”’[2]

To commemorate the great victory, the King himself made a pilgrimage to Mariazell and donated the painting decorated with precious stones of the Virgin Mary to the church, which is otherwise attributed to Sienese painter Andrea Vanni (died c. 1414). To this day, believers visit the site and pray before the image.[3]

However, the dating of the military event that led to Louis the Great donating the picture to the church has long been a problem for researchers, since the Hungarian royal army, much less Louis the Great himself, did not directly clash with the Ottomans. What is even more puzzling is that Hungarian court chroniclers do not mention such a conflict either.[4]

What we do know from other sources is that Louis had already been in contact with Mariazell in 1358 when he asked for papal privileges. We also know very well that Louis was incredibly skilled at diplomacy and presenting imperial propaganda. The King and the Queen Mother’s unparalleled pilgrimage and diplomatic travels in Europe in their day are also evidenced by the array of gifts placed in churches throughout Europe. For example, he donated a piece of the tablecloth from the Last Supper to the Duke of Austria, which was then preserved for many years in the treasury of St Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna. Thus, it would not have been unprecedented for the King to have made a military victory of regional importance a European one, which Louis did magnificently at Mariazell.

Nevertheless, it was only after the death of Louis, around 1390, that the Ottomans reached Hungary’s borders, and soon they were claiming the richest southern territories of the country at the time. It is certain, however, that

the first years of the Ottoman–Hungarian clash of great power interests fell during the reign of Louis the Great, in the 1360s.

Turkish troops conquered Drinapolis (today’s Edirne, Turkey), one of the pride of the Byzantine Empire, in 1361/1363, and made it their capital until the conquest of Byzantium in 1453. Then, within a few years, they had taken Plovdiv, Sofia, Nis, and Thessaloniki, too. The situation in the Balkans was both promising and unfortunate for Hungarian diplomacy: for the expanding Hungarian power, the disintegration of the Balkan states offered opportunities, but at the same time, it entailed serious political and military risks as well.

Under such circumstances, a Bulgarian–Byzantine clash broke out in 1365, where the Bulgarians, led by Tsar Ivan Shishman, were already supported by Ottoman auxiliary units.

Louis saw the opportunity and, in support of Byzantium, his troops attacked from the north, even requesting several transport galleys from Venice from early 1365.[5] As a result of the campaign, the Bulgarian town of Vidin (Bodony in Hungarian) on the Danube bank came under Hungarian rule, where the Vidin province was established. Louis linked it with the Temes reeve, which thus provided the conquest with a hinterland and logistical support. In 1366, Louis received Byzantine Emperor John V (Ioannes) in Vidin, then in the interior of the country, to negotiate about Western aid. However, the success did not prove lasting, and the Hungarians were soon forced to abandon the town.

This type of encounter has taken place several times in the same decade, in 1365, 1368, and 1375 as well.[6] In the absence of historical records, it is difficult to know which of the vows of this warlike, deeply religious King, who repeatedly fought in mortal danger, can be linked to his founding of the Mariazell Basilica. Of course, Louis may also have been commemorating the wars he would have liked to have fought but never had the chance to.

The King founded or donated to several churches that can be linked to campaigns even without written records, such as the ones in the villages of Márianosztra for the 1352 campaign against the Lithuanians and Máriavölgy for the 1375 campaign in Wallachia (Havasalföld).[7] Thus, the foundation charter for the Hungarian chapel in Aachen probably rightly mentions the merits of the Hungarian kings in battles and in defending the frontiers.

Of course, these deeds can also be seen as a conquest of Hungarian ‘imperialism’ and an action against the Orthodox, as many historians still believe. There are historians, too, who hold Louis the Great responsible for underestimating the Ottoman advance in the Balkans and not doing his best to avert the threat. They blame him for having specifically hindered the common European struggle with his wars against Naples and Venice in the West and think what he did in the Balkans was nothing more than the self-serving expansion of the Hungarian power. These accusations are extremely serious. Nevertheless, it must be acknowledged that

this was perhaps the last time Hungary was in such a decisive position that it could have influenced the course of world history by its own efforts.

Could helping Byzantium and preserving the Empire have saved Europe from centuries of Ottoman occupation? However appealing, this argument cannot be entirely accepted: by that time, the Balkan state structure was already disintegrating into unviable principalities independently of any Hungarian influence.

By this time, the Byzantine Empire was completely unable to organize effective resistance and integrate the Balkan states. At the same time, there was no common policy in Europe that would have actually supported any Western state, such as Louis the Great’s Hungary, to lead an anti-Ottoman campaign.

Meanwhile, the Ottoman Empire was growing so rapidly demographically, economically, and militarily that Hungary could not keep pace with it with any hope of success. In light of all this, Louis the Great’s policy of trying to establish a system of allied states on Hungary’s frontline does not seem at all misguided. The final halting, or even the suppression, of Turkish expansion presented Louis with a militarily and politically impossible task, which the King tried to solve according to the ‘Realpolitik’ system of arguments, and which he believed could be stopped in the Balkans.

Nevertheless, it may well be that the foundation of the Mariazell Basilica was not linked to the actual anti-Ottoman warfare until decades later, in the early 15th century. By then, the Ottoman cavalry had already reached Austria, and had already ravaged as far as Mariazell by 1420. When the Ottoman threat became an everyday reality, it was taken for granted that the Crusaders could only re-found such a significant church as a result of their successes against the Ottomans.

The Mariazell Basilica not only became a family shrine of the Habsburgs but retained its popularity with Hungarians, too—15th-century wills from Pressburg (today’s Bratislava, Slovakia) and Sopron testify that it was usually visited by Hungarian pilgrims. Count Pál Esterházy (1635–1713), Palatine of Hungary, became one of the church’s most important patrons during the Baroque period. He himself made 58 pilgrimages to the church, in 1691 with a group of nearly 10,000 people.

In the 18th century, Hungarian chapels were founded within the Basilica for St Stephen, St Emeric, and St Ladislaus. In Hungary, a replica of the statue of the infant Jesus sitting at the right hand of Mary was placed in the chapel of Dömölk (now Celldömölk), followed by other foundations in Óbuda (Kiscell) and Bratislava.[8]

After 1945, the Basilica became the spiritual centre of Hungarian emigrants,

and it is no coincidence either that Cardinal József Mindszenty, who died in Rome in 1975, was also buried there in the chapel of St Ladislaus.

[1] Robert Born, ‘The Turks in East Central Europe, with a Focus on Hungary, the Romanian Principalities, and Poland’, in Bent Holm and Mikael Bøgh Rasmussen (eds.), Imagined, Embodied and Actual Turks in Early Modern Europe, Vienna, 2021, pp. 105–111.

[2] L. Bernát Kumorovitz, ‘I. Lajos királyunk 1375. évi havasalföldi hadjárata (és ‘török’) háborúja’, Századok, Vol. 117, 1983, pp. 919–982.

[3] Charles Zika, ‘The Treasury Image of Mariazell: The Materialisation of Hope, Assurance and Security’, Emotions: History, Culture, Society, Vol. 7, 2023, pp. 52–75.

[4] Kornél Szovák, ‘König Ludwig der Große und Mariazell’, in Walter Brunner et al. (eds.), ‘Mariazell und Ungarn. 650 Jahre religiöse Gemeinsamkeit’, Veröffentlichungen des Steiermärkischen Landesarchives, Vol. 30, 2003, p. 86.

[5] Joseph Gill, ‘John V Palaelogus at the Court of Louis I of Hungary, 1366’, Byzantinoslavica, Vol. 38, 1977, p. 3.

[6] Sándor Papp, ‘Hungary and the Ottoman Empire (From the Beginning to 1540),’ in István Zombori (ed.), Fight Against the Turk in Central-Europe in the First Half of the 16th Century, Budapest, 2004, p. 53.

[7] Terézia Kerny and Szabolcs Serfőző, Die Schlacht Ludwigs des Großen gegen die ‘Türken’: Ursprung einer Legendenkonstruktion. Ungarn in Mariazell – Mariazell in Ungarn: Geschichte und Erinnerung, Hg. v. Péter Farbaky – Szabolcs Serfőző, Budapest, 2004, pp. 47–60.

[8] Gábor Tüskés and Éva Knapp, ‘Mariazell und das ungarische Wallfahrtswesen im 17. und 18. Jahrhundert’, in Péter Farbaky and Szabolcs Serfőző (eds.), Ungarn in Mariazell – Mariazell in Ungarn: Geschichte und Erinnerung, Budapest, 2004, pp. 84–92.

Related articles: