The notion of being a ‘border nation’ is deeply embedded into Hungarian historiography and national consciousness. This narrative differs from the classic frontier myth, as it is not expansionist and colonizing in its nature—on the contrary, it revolves around the duty to protect, and defend a civilization from the encroachment of others, rather than to occupy. Hence the nickname for Hungary, ‘the bulwark of Christendom’ that the country has rightfully earned with its heroic deeds over the course of a millennia. Aside from Hungary itself, the territory of the present-day Serbian Vojvodina is where this national myth of being a bulwark was forged.

While Vojvodina had not yet formally evolved into a distinct entity during that period, its fortresses, such as Zimony and Pétervárad, had already begun to play a crucial role in defending Hungary against its enemies.

During the early Middle Ages, Slavic farmers settled in Vojvodina. With the arrival of Hungarians, however, a significant demographic transformation began.

The Hungarian ethnic dominance in the region lasted until the Ottoman Conquests in Europe, when southern Slavic—mostly Serbian—nobles, military and clergy alike, started to cross the border into Vojvodina, seeking shelter from the conquests in their northern Christian neighbour. Hungary was willing to lend a helping hand, and as a consequence of that policy, several Serbian settlements appeared all over the historic Hungary. Many were exempt from taxation and were offered to live in Hungary with full rights, in exchange for serving to protect the newly emerged Hungarian-Ottoman borderland, part of which now lay in Vojvodina.

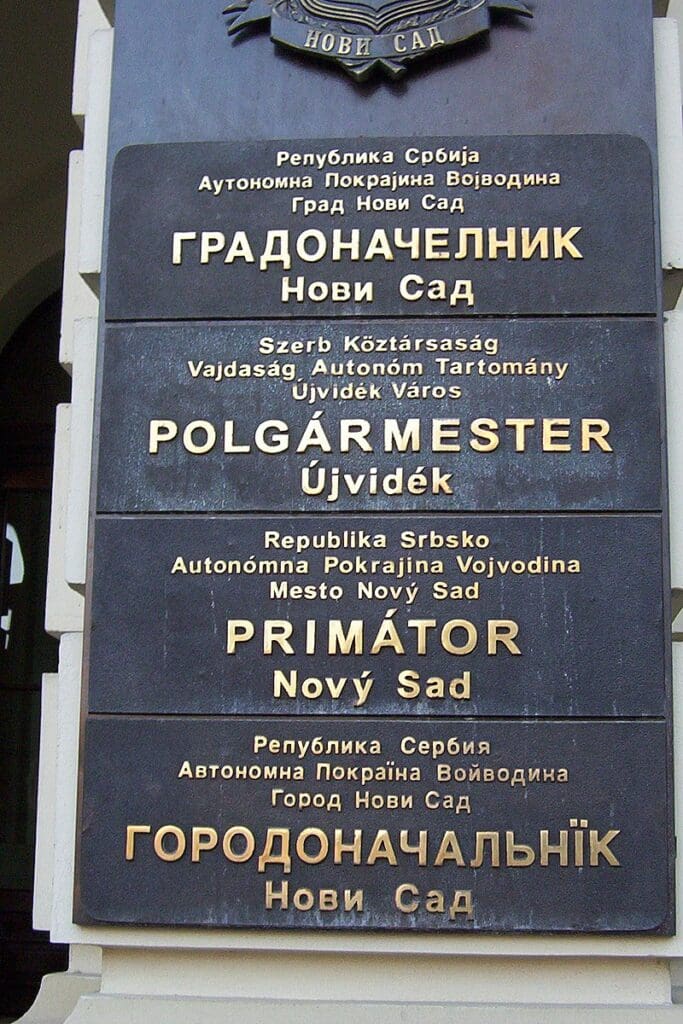

The name of Vojvodina also alludes to its conflict-torn past—

both in Hungarian and Serbian, as well as in four other official languages of the region, Rusyn, Croatian, Romanian and Slovak, the name of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina is derived from the title of voivode that denotes a military governor of a province.

Having Serbs serving on the frontiers of Hungary resisting Ottoman attacks became widespread during the reign of Matthias Corvinus, who sought to recruit foreign nations for the sake of strengthening Hungary’s defences. Vengeful Serbians who were forced out of their homeland were eager to take the opportunity and fight against the Turkish invaders. Unfortunately, Hungarian efforts to stop these invaders were too late, and the Ottomans could not be stopped. The chain of fortresses in Vojvodina, such as Pétervárad and Zimony, after years of heroic struggle, eventually fell into the Ottoman hands. The victorious Turkish military campaigns not only displaced even more southern Slavic communities, forcing them to migrate northward, but also inflicted significant losses on the Hungarian population, causing a substantial decline in their number.

Following the event known as the Great Migrations of the Serbs, the ethnic equilibrium of former Southern regions of the Kingdom of Hungary changed once and for all in favour of Southern Slavs.

By the 18th century, with the region’s incorporation into the Habsburg monarchy after the departure of the Ottomans, the ruling dynasty had restored the old Hungarian practice of using Croats and Serbs as border guards. The so-called Military Frontier was established on the Southern edges of the Empire. Much like in the past, under the new patronage, the immigrant Slav population fleeing the Ottoman Empire was granted land and an array of privileges in return for defending the Empire against Ottoman incursions. The package of granted rights was expanded, allowing the South Slavic population to elect their local leader, called the Vojvode. This development marked the emergence of Vojvodina as a distinct entity set apart from other border territories.

Desolate and devastated after the Turkish wars, Vojvodina became the Austrian, and later Austria-Hungarian Wild West.

Albeit it was located in the middle of Europe, hardly anything survived after centuries of fighting—as a result, the Viennese court recognized the necessity of implementing resettlement and colonization initiatives for the much-needed revitalization of the war-torn region. Following these initiatives, in the 18th–19th centuries, the region witnessed an influx of new settlers from all across the Empire, including but not limited to Jews, Germans, Hungarians, Romanians, Serbs, Croats, Rusyns, Slovaks and others.

The newly arrived settlers created several new towns and villages, such as Újvidék (Novi Sad), now the centre of the region, but also repopulated some old ones, such as Szabadka (Subotica), Szombor (Sombor), Pétervárad (Petrovaradin), and many others. After the Austro-Hungarian compromise of 1867 and the abolishment of the military frontier, Vojvodina witnessed a remarkable economic development under the jurisdiction of the Hungarian crown, thanks to its inhabitants’ relentless efforts and unwavering determination to bring the region back to life.

Despite the horrendous impact of the two World Wars, the region’s separation from Hungary and the Yugoslav wars, which inflicted losses on all the ethnic groups living in the region, the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina is still a highly developed part of Serbia with a prosperous economy and close ties to Hungary.

Vojvodina is rightfully regarded as ‘the breadbasket of Serbia’,

supplying the country with meat, and corn. The region’s diversified economic activity also includes petroleum and natural gas extraction near Vršac and Kikinda. The settlement of Pančevo is, in turn, home to Vojvodina’s heavy industry complex. Governmental leadership is represented by Igor Mirović, whereas István Pásztor, an ethnic Hungarian man from Vojvodina is the leader of the Alliance of Vojvodina Hungarians, a regional political party, who is also the president of the regional assembly.

Numerous landmarks in Vojvodina stand as enduring testaments to the rich Hungarian heritage of the region. For instance, a castle near Nagybecskerek (Zrenjanin), named Kaštel Ečka, is the place where the famous Hungarian conductor and composer Ferenc Liszt performed. The Pétervárad (Petrovaradin) Fortress, initially built by Cistercian monks and King Béla IV of Hungary upon the ruins of the ancient Roman fortress of Cusum, is a relic of the Turkish-Hungarian wars, the stones of which bear silent witness to the courageous Christians defenders of Hungary and Europe. In addition, the Hungarian Secession buildings of Szabadka, such as the Raichle Palace, Municipal Library, City Hall and Vojnića Palace also testify to the region’s Hungarian cultural legacy.

Related articles: