The following is the first instalment of a three-part paper[1]. (Editor’s note: For the sake of coherence, the introduction and the conclusion of the analysis are published at the start and at the end respectively of each instalment.)

History did not end after the fall of the bipolar world order in 1990. The ‘West’ failed to take advantage of the historical situation to homogenize the world in its own image and soon the polarization of the world began/continued.

Certain actors started to ask for, if not demand, a leadership role, if not global, at least regional, something the ‘West’ had never granted them, on the contrary, it had made them its targets. As a result, on the geostrategic map of the Old World, a great chessboard, many ‘pieces’ have been given or have won roles and opportunities that they have begun to take advantage of in recent decades. The Western euphoria soon dissipated as it had to face the cultural and religious diversity of the world. Many cultural and religious divergences and the resulting diverging trends have succeeded in breaking the coveted coherence. The ‘West’ has not noticed or understood this—it is, therefore, surprised to see that other regions of the world, other global or regional powers, following different development paths, are succeeding economically and politically and are slowly

building an alternative reality to the ‘West’.

The ‘West’ has realized that if it plays the chess game with the current distribution of chess pawns, according to the traditional rules of chess, it will be checkmated in a few moves. The following paper will examine the challenges and even the breaking points that threaten the global influence and engagement of the ‘West’, including the EU, and that could have far-reaching consequences for the future of the ‘West’, and for Western values itself.

In the last two years, two wars have shaken the world, or at least the global public, which have extremely, if not permanently, divided the world, and accelerated the emergence of two great camps: the ‘West’ and the ‘East’. In addition, the expansion of a new world trade and economic platform and network, the Alliance of the BRICS countries, is now having a major impact on the coherence of the world, which had hitherto been dominated by the ‘West’. The present paper aims to illustrate the three fault lines that are about to redraw the map of the global geostrategic balances of the Old World.

***

The Russo–Ukrainian War

The Russo–Ukrainian war resulted from a predictable Russian reaction[2] that could have been foreseen since 2014. It was obvious that Russia, which is still an empire, could not and would not allow NATO bases, possibly storing nuclear weapons, to be located in Moscow’s range of vision, in Ukraine, a country that was set to become a NATO member. Similarly, the United States (would have) had every right not to allow Soviet Russian bases with nuclear weapons in Cuba. From this simple fact, it could be predicted with absolute certainty that the Russians would attack and try to invade Ukraine, or, more precisely, overthrow the pro-Western Ukrainian government and prevent further NATO expansion to the east.

The result was a protracted military conflict and the polarization of the world. The ‘West’ has almost completely decoupled itself from Russia—in terms of symbolic politics and political marketing, completely, and with regard to the economy, mostly (although the free flow of capital has no political and moral concerns and obstacles and will find its way to Russian resources and the Russian market, and Russian raw materials will also find their way to Western markets).

All this has forced Russia to and made it interested in starting or rather pursuing with greater vigour, together with China—which the Western mainstream sees as a rival, what’s more, an enemy—

the construction of a new world order in rivalry with the ‘West’;

an emerging alliance system that could consist of a number of other countries that do not have friendly relations with the ‘West’ (including the United States), such as Iran with the Shi’ite countries, Afghanistan, the whole of Inner Asia, and perhaps even Pakistan.

Geostrategic Consequences

The Russo–Ukrainian war has divided the world and left Russia almost completely isolated from the West, but has also set in motion geostrategic planning processes, embodied in the BRICS enlargement, which could help accelerate the West’s decline (see below). This new and expanding alliance, based on the Russian–Chinese Axis, has not only considerable economic but also military power, and even a potential that exceeds that of the ‘West’ in terms of nuclear capabilites.

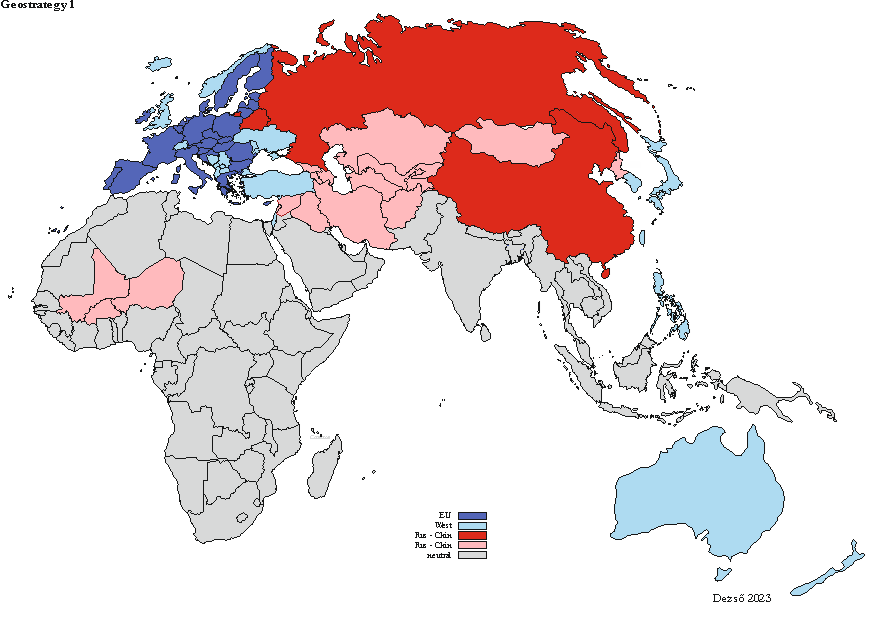

Map 1 shows who could join this political/economic and perhaps military alliance. This map also leaves more questions open than it answers. Such questions include:

1) Who would the countries of Indochina (Southeast Asia) pull towards if polarization were to disrupt the existing world order; also, how strong or overwhelming is Chinese influence in the region?

2) The countries of the Arab world also have many ties to the Russian–Chinese Axis, and some of them have already made it clear by joining BRICS that they see their place in the (economic) alliance of emerging regional powers vis-à-vis the ‘West’ (as it will be discussed in the next part of this series). In addition, the ‘West’s’ natural and self-evident support for Israel against the Islamist terrorism of the Palestinian Hamas has further polarized the region and alienated the unconditionally pro-Palestinian people of the Arab world, and with them, their governments, from the ‘West’ (see below) and brought them closer to the pro-ceasefire and pro-peace Russia, whose representatives received a Hamas delegation in Moscow to negotiate peace and the fate of Gaza.

3) Many African countries are also taking a cautiously neutral stance. As we have seen in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, the opposition to the colonial past and the growing Chinese and Russian commercial and partly military (Wagner Group) influence in the region could ultimately push these countries to break with the ‘West’. Despite all these considerations, the countries of the above-mentioned regions are marked on Map 1—in this section—in neutral grey.

The break discussed in this chapter was the result of a conscious decision by the ‘West’.

Conclusion

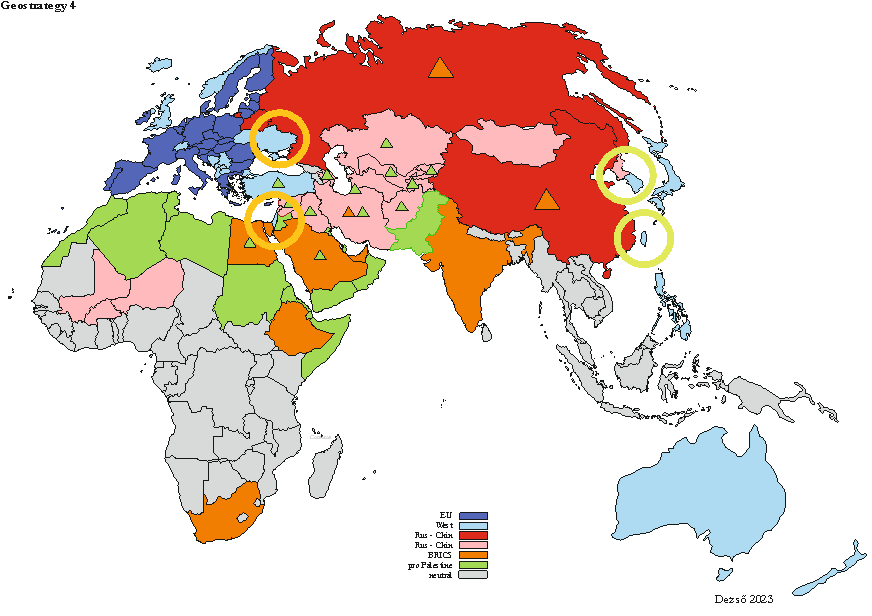

The fault line described above and in the next two parts of this series of articles carries with it the danger of the Western and the EU elites, which are largely unaware of the many directions of development in the world, becoming increasingly isolated. A geostrategic environment is developing around us which, as Map 4 shows, is slowly bringing the ‘West’, especially Europe’s neighbours and rivals, onto a common platform, along different principles and interests.

In such a geostrategic context, the current EU leadership seems to be oblivious to, or deliberately ignores, the threats to the future of the EU and the Western world, and pushes themes, such as gender ideology and open society, that are largely symbolic, distracting attention from the real hazards and weakening the EU from within rather than strengthening and enhancing its internal coherence.

The EU—at the latest in light of the mass pro-Palestinian demonstrations in Europe after the Hamas terrorist attack (see above)—must finally realize that uncontrolled immigration is not the solution, but the problem itself, since, contrary to the expectations of Western elites, it has not had the ‘fertilizing effect’ on the economy or society. On the other hand, the unwanted processes that inevitably accompany the arrival of large numbers of immigrants from other cultures and backgrounds occur daily, whether along Hungary’s southern borders or on the streets of Western Europe. The greatest danger of all is the security threat posed by Islamic terrorism. The pro-Palestinian demonstrations, for example, raise the question of whether the Muslim population in Europe can distance itself from the Islamic radicalism of Islamic terrorism, conflated with the liberation ideology of Hamas.

The Russo–Ukrainian war is the most pointless undertaking from the point of view of the EU’s geostrategic interests. It is the bloodiest armed conflict since the Iraq–Iran war, with at least half a million (500,000) victims, the same number of crippled families, seven million refugees, and a partly destroyed country indebted for at least 50 years. Looking at the current and potential crisis zones, from a strictly geostrategic point of view,

the Russian–Ukrainian front, with its symbolic messages, is the most meaningless and bloodiest conflict that is not in the interest of the ‘West’.

Apart from the crippling of Ukraine, it is the EU economy that has suffered the most (petrol prices out of control, inflation, the consequences of the loss of cheap energy for the private and industrial sectors, a dramatic deterioration in the EU’s economic competitiveness, and the list goes on). In addition, the ‘West’, including the EU, has taken on financial burdens that are putting a strain on its budget. Moreover, Western strategic ammunition stocks and arms production have come under unprecedented pressure, posing a substantial threat to the security of the ‘West’. It must also be alert to other crisis hotspots (Israel) and avoid any escalation, as it is probably unprepared for challenges of this scale. If the two other crisis hotspots in the Far East (Korean Peninsula and Taiwan), where there is a threat of a military conflict, were to erupt as well, the ‘West’ would be faced with an almost insurmountable problem from a geostrategic and military point of view. At the same time, it can also be said that for some time now the EU has been the most rapidly arming political community.

In summary, the geostrategic environment around the EU and Europe, partly as a result of the EU’s deliberate decision (breaking with Russia), partly through no fault of its own (the Palestinian issue), and its attitude of only observing the changes in the global economic environment from afar, without being able to influence them in any meaningful way (BRICS+6), has reached a situation that risks isolation.

From the point of view of maintaining the current form and values of the ‘West’, the continuation of a migration policy is life-threatening, because it is triggering internal processes in the Western world which, willy-nilly, will result in the sacrificing the core values of the ‘West’ on the altar of the progressive philosophy of inclusion, and in the weakening from within of its geostrategic position the losing of which could have fatal consequences in a world where the axis of global economic development, population growth, and history no longer revolve around Europe.

Europe and the European Union no longer sit at the global geostrategic chessboard as players,

but are at best kibitzers, even if the EU leadership refuses to acknowledge this.

If the ‘West’, of which this author is an integral and committed part, does not change its present policy, it will soon find itself in a geostrategically hopeless situation.

In the next two parts, the geostrategic significance of the Israeli–Hamas conflict and the role of the BRICS countries will be discussed.

[1] This paper is part of a larger comprehensive geostrategic study by the author. As it stands, it raises more questions than answers, but its basic premises allow clear geostrategic conclusions to be drawn.

[2] Western strategists who did not know this should resign, and those who knew it and allowed events to spiral into a war should also resign.