The Hungarian Revolution and War of Independence (or the Hungarian Uprising) of 1956 is one of the most important chapters of Hungarian history. The revolution, which started on 23 of October, was suppressed during November: the Soviet invasion, which ended the revolution, started on 4 November. While less prominently than 23 October, this date is also officially remembered in Hungary, and has been designated a National Day of Mourning.

Prelude

On 28 of October, the Communist-appointed, but reformist prime minister, Imre Nagy announced that the government would accept the demands of the revolutionaries. A ceasefire and universal amnesty were declared. A multi-party system was created, and the reorganized larger parties—which played prominent role during the short-lived semi-democracy between 1945 and 1949—were invited into the government. As another focal point of the reforms, on 31 of October, Hungary announced its neutrality, and withdrawal from the Warsaw Pact. It was also the day when the end of the Soviet occupation was officially announced, as Russian troops pulled out of the country. However, it soon turned out that Moscow was only playing for time, and the joy over the Soviet military leaving was short-lived.

But on 28 October, it still seemed that the revolution, which started five days earlier, was victorious. Apparently, Khrushchev first wanted to make a compromise and allow Nagy to remain in office, practically assenting to the reforms out of necessity. However, the announcement regarding neutrality was unacceptable to Moscow since it would have created a gap in its chain of client states stretching towards the West. It was in fact on the last day of October that the military option was officially decided on. At the same time, the Soviet leadership also started to recruit the members of puppet government in Hungary. Not having become compromised during the Stalinist era was an important criterion of the selection of the leaders of the new cabinet. At the same time, being fully loyal to the Soviets was a must. Thus, the former Hungarian ambassador to Moscow, Ferenc Münnich, and a formerly reformist politician, János Kádár were chosen. As he was relatively popular, Kádár was nominated for premiership. These two politicians were flown to Moscow to prepare them for setting up a government after the Soviet invasion.

Preparations

The Soviet troops in Hungary had been prepared for the reversal of the seeming pullout at a very early stage. The withdrawn units were stationed near Hungary, just across the border in the Subcarpathian region in Ukraine, where additional troops also arrived. Also, Soviet soldiers never left some garrisons in Hungary, such as the Tököl military airport, where the troops were placed on alert.

Worried by these developments, the Hungarian government summoned the Soviet ambassador, Yuri Andropov;

however, he could not offer a plausible explanation. According to some sources, this was the moment—as opposed to October—when the government finally decided to declare neutrality. Therefore, it cannot be taken for granted that had Imre Nagy not declared withdrawal from the Warsaw Pact some degree of independence could have been preserved.

It is important to note that the international situation was not in favour of Hungary either. The great powers were focused on the Suez Crisis in Egypt. Also, a military intervention in the heart of Europe would have been very risky. It was in this context that at the end of October, President Eisenhower announced that the United States does not consider Hungary its ally. Thus, Washington practically signalled that it would give a free hand to Moscow, and assent to the preserving of the Cold War status quo in Central Europe.

The Soviets continued to prepare for the military aggression in the first days of November. By 2 November, Soviet presence in Hungary had been more than doubled. On this day, Marshall Konev, Commander in Chief of the Warsaw Pact forces, set up a military HQ in Szolnok. So, while the Russian troops did not engage in battle for the time being, it became more than clear that Moscow intended to crush the revolution.

Operation Whirlwind

The Soviet invasion began on 4 of November, under the codename ‘Whirlwind’. Just before the military operation, Kádár and Münnich were transported to the Subcarpathian region of Ukraine. As a fig leaf to hide the brutal aggression, on the morning of 4 November, the formation of a counter-government under the name ‘Revolutionary Workers’-Peasants’ Government of Hungary’ was announced, that, if was claimed, asked for the assistance of the Soviet Union to defeat the counter-revolutionary, fascist rebels. At the same time, the Soviet main forces crossed the border from Ukraine, and headed toward Budapest. The capital city had in fact been completely encircled completely by the Soviet troops that had remained in the country by the eve of the 3rd.

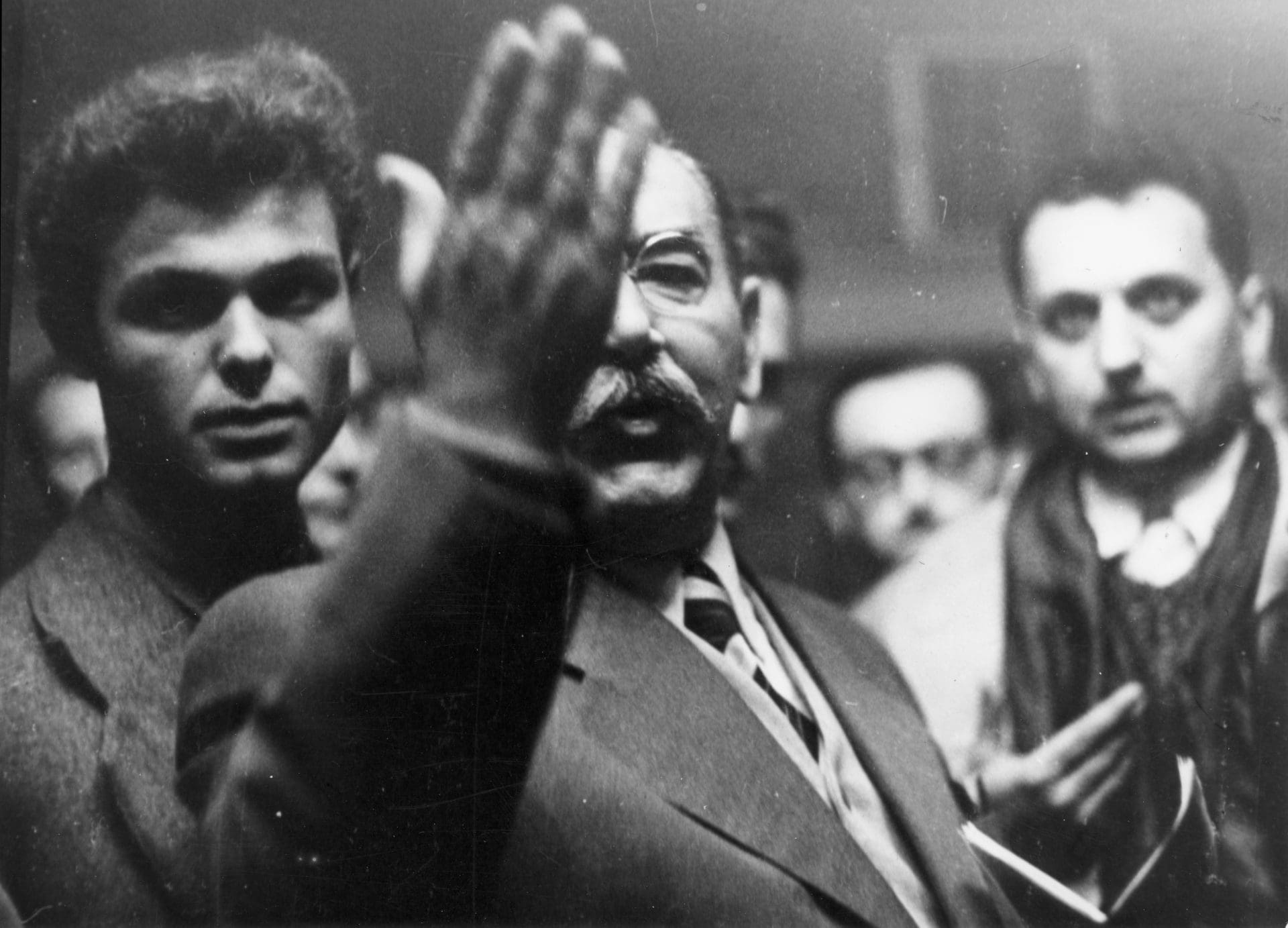

Prime Minister Imre Nagy held his famous, short, and dramatic radio speech on the morning of 4 November, announcing the Soviet invasion and pledging to resist the aggressors.

‘This is Imre Nagy, chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Hungarian People’s Republic, speaking. In the early hours of this morning, the Soviet troops launched an attack against our capital city with the obvious intention of overthrowing the lawful, democratic, Hungarian Government. Our troops are fighting. The Government is in its place. I inform the people of the country and world public opinion of this.’

Soon after the announcement, Nagy was forced to flee to the Yugoslav embassy.

During the early morning of 4 November, the Soviets penetrated Pest from two directions.

One set of units came from the south via Soroksári Road, while another from the north via the Váci Road. Thus, the Soviets had effective control over the bridgeheads and main routes inside Budapest even before the first shots were fired. A third force entered from Buda, and that was the one which engaged in the first actual combat. Units of the Hungary Army resisted Soviet troops not only in Buda, but also in Pest: among others, in Soroksár and Kőbánya. However, the regular troops were swiftly neutralized, and the Soviets continued their onslaught from all directions. By noon, their troops secured key positions in the inner city as well, including capturing the Parliament and the Ministry of the Interior.

The Soviets also shelled Budapest heavily, especially Csepel, where resistance was concentrated, but also other industrial centres. Soviet tanks also often fired into residential buildings indiscriminately to break the spirit of resistance. It was mostly the revolutionaries, therefore primarily civilians, who offered stronger resistance, since these fighters could engage in partisan-style fighting. There were many scattered pockets of resistance, the most notables in Budapest being the Corvin Passage in Pest and Széna Square in Buda. Outside of Budapest, the resistance fighters in the Mecsek mountains must also be mentioned. Due to the firm resistance, the power of the puppet government was only consolidated by 11 November, when Csepel and Dunaújváros, another important industrial hub, succumbed; however, smaller acts of sabotage, sporadic armed resistance and especially political opposition continued until early 1957.

Conclusion

After initially appearing open to talks, Moscow swiftly opted to reverse its concessions and violently crush the revolution. It is up to debate whether the Soviets ever considered those concessions seriously and if it was only the declaration of neutrality that hardened their stance, or whether the whole negotiation process was a smokescreen. What is certain is that the Hungarian revolutionaries took a last heroic stand against one of the strongest armies in the world, and that their resistance delayed the Communist consolidation by months.