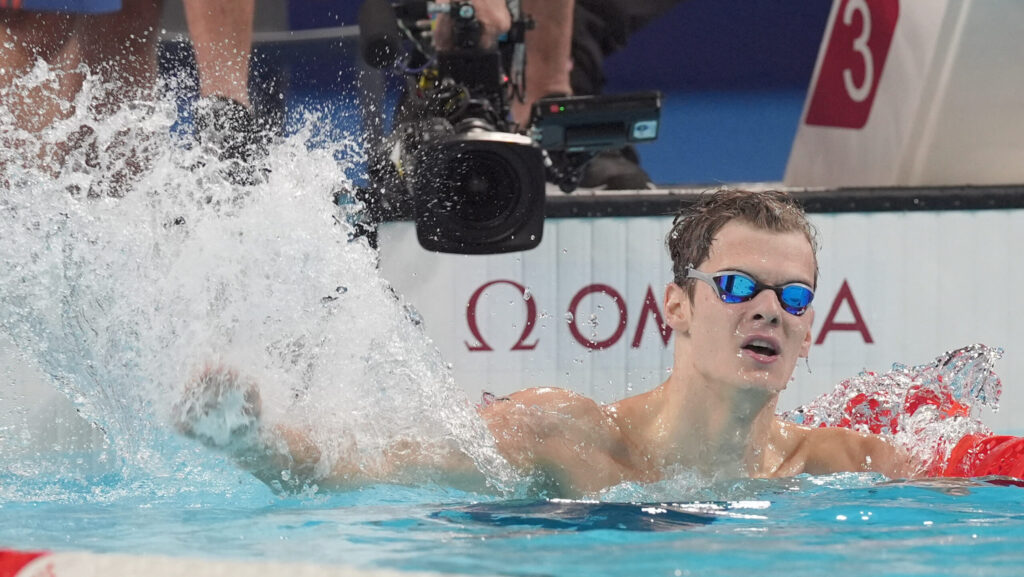

This essay was first published in the Hungarian Review on 8 August 2017. The author, Mátyás Sárközi (Budapest, 1937) is a writer and journalist, who settled in London towards the end of 1956 as a Hungarian refugee. Within a few weeks after his arrival he became a student of St Martin’s School of Art, studying book-illustration. Later he became employed by the BBC’s Hungarian Section. Since 1990, he has been spending part of his time in Budapest and writing for and appearing in the Hungarian media. He was awarded the Kossuth Prize in 2020.

Extra Hungariam non est vita, si est vita, non est ita—stated a Hungarian scholar three hundred and fifty years ago in a Latin dissertation. The much-quoted sentence has been interpreted in more than one way. Ardent patriots maintain that outside Hungary there is no life whatsoever, just as there is no life (perhaps) on Mars. Others would translate these words differently: ‘All right, there is no life outside Hungary, but if there is some kind of life there, it is not the same thing.’

As a Hungarian living in Great Britain since 1956 I tend to agree with an extended version of the second interpretation: a Hungarian’s life outside Hungary is definitely quite dissimilar to the lives of those who remained there, but it is still a life, not necessarily worse, and by making an effort, it can retain its Hungarian qualities. If, for example, one happens to be a Hungarian writer living outside of his native land, the language, one’s mother-tongue, can be a lasting and unbreakable bond.

On 4 November 1956, Soviet tanks and troops crushed Hungary’s national uprising against Communist oppression. Faint resistance continued until mid-November, altogether over 2,500 Hungarians and 700 Soviet soldiers were killed in the conflict, and by the end of the year 200,000 Hungarians fled as refugees. An extraordinary operation sprang up in neighbouring Austria, not only to care for them, but also to move them on. Within weeks Hungarian refugees began to settle in thirty-seven different countries of the world. The US accepted the largest number (19,655), followed by Great-Britain (13,018) and West Germany (10,934). Later Canada took in more than 20,000 and 11,471 refugees remained in Austria. France first tried to set a limit of 7,000, but finally 13,000 Hungarians ended up there.

In October 2006, on the 50th anniversary of the Revolution, The Guardian interviewed some Hungarian refugees who settled in Britain.

I was one of the interviewees, remembering my escape fifty years before:

‘As a 19-year-old trainee journalist, I walked across what turned out to be a minefield into Austria and soon found myself in a refugee camp in Graz. One day in December a stocky middle-aged lady, wearing the green uniform of WVS (the Women’s Voluntary Service) came to the camp and asked all those who wanted to go to Britain to line up behind her. I had a vision of Britain as a dark place with cobbled streets, Oliver Twists running about picking pockets. No wonder that I was pleasantly surprised finding a very different world after my arrival. Students were welcomed by the universities, they all wanted Hungarian freedom fighters, heroes of the barricades. The British are always on the side of the underdog. To be honest, not all of us refugees were genuine fighters during the revolution, but in one way or another, we had indeed all turned against Communist oppression. Therefore, after the Russians‘ return, many of us took the opportunity to escape through the temporarily unguarded border, in order to start life anew settling in Western democracies.’

The 1956ers were mostly young and eager to prove their worth. For a while in Britain Joe Bugner was the most celebrated newcomer. Led across the border by his parents as a child, fifteen years later he became the British heavyweight boxing champion, fighting Muhammad Ali for the world title. Eventually other Hungarian refugees became just as acclaimed. For example another child immigrant, George Szirtes is now a well-known British poet, winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize. A young medical student who was offered a place in Oxford’s famous Merton College after his arrival, later became one of the world’s leading molecular cardiologists. György Radda went on to head the British Medical Research Council, and on his retirement in 2000 the Queen made him a Knight of the British Empire.

In general, the 200,000 Hungarian refugees proved to be an asset to their host countries

and produced many brilliant careers in various fields, Just to mention two of them: Andrew Grove (András Gróf), who died in 2016, was the Californian co-inventor of the microprocessor, and George (György) Oláh, who won the 1994 Nobel Prize for his contribution to carbonation chemistry.

Because of the nature of the 1956 revolt – started by students and intellectuals –there was a large number of either already practicing or would-be writers and journalists among the refugees. While the students headed towards the best-known university towns, the men of letters hoped to join Western radio stations broadcasting in Hungarian. The BBC’s Hungarian Section, established in 1939, had a tradition since its very beginnings of employing writers. During the Second World War Ferenc Körmendi, who in 1932 won an international competition organised by three leading British publishers with his novel Escape to Life (Budapesti tavasz), worked there as a translator/announcer, just like Paul (Pál) Tábori the prose writer and George (György) Tábori the playwright.

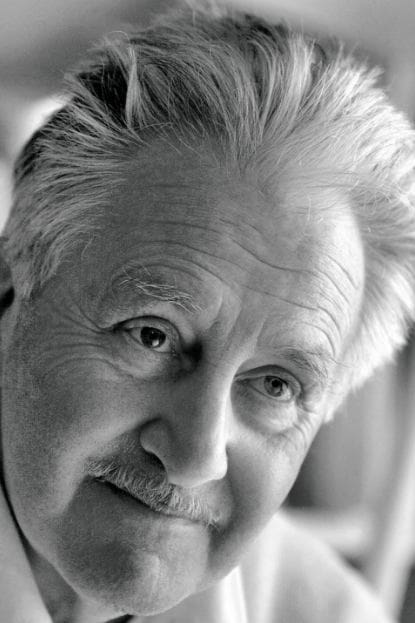

During the Cold War years George (György) Mikes wrote seething but extremely funny anti-Communist cabaret sketches for the BBC, but when his satirical book How to Be an Alien became an enormous success, he left the Corporation to become a freelance writer. (During the 1956 revolution, the BBC’s External Services decided not to send correspondents to Hungary, feeling that perhaps it would be an intervention in the country’s internal affairs. But George Mikes was employed by BBC Television to send on-the-spot reports.)

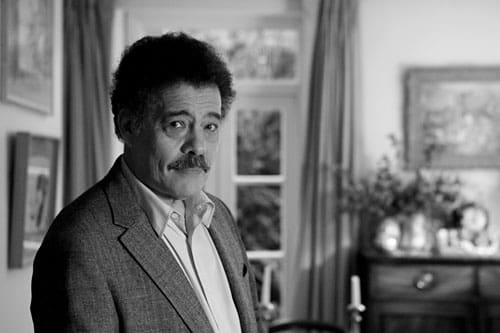

In 1951, the recent émigré László Cs. Szabó, who left behind his professorship of cultural history at the Budapest Academy of Fine Arts, joined the BBC’s Hungarian Section and soon became one of its star broadcasters with his radio-essays and radio- plays. Perhaps one could say that before 1956, three established literary personalities were most revered within the emigrant community for their high quality prose and also for their political integrity: László Cs. Szabó, Zoltán Szabó and Sándor Márai. The last two were outside contributors to the Munich-based, American-sponsored Radio Free Europe. The two Szabós (not related) became the leading lights of post-1956 Hungarian literary life abroad, while Sándor Márai, having a different kind of personality, stayed away from emigrant politics and lived withdrawn into his Californian ivory tower. (In 1989, close to his ninetieth birthday, embittered by personal tragedies and the wrongs of the world, he committed suicide.)

When the huge mass of new Hungarian refugees began to settle all over the West, László Cs. Szabó seemed to be surprised to find so many young intellectuals among them. He echoed a well-known newspaper headline of the 1930s, according to which ‘Ten thousand journalists are flocking to Budapest’ (those who lost their jobs when provincial papers were closing down during the depression). ‘A thousand writers are flocking to the West’, wrote Cs. Szabó in a Hungarian emigrant literary magazine. And he finished the sentence with the remark: ‘and they are all twenty-year-olds’.

What did he mean? Was he afraid that these young writers will use up the available space in the Hungarian diaspora’s quality publications like Látóhatár (Horizon) in Munich or Katolikus Szemle (Catholic Review) in Rome? It is more likely that Cs. Szabó had simply expressed his honest surprise.

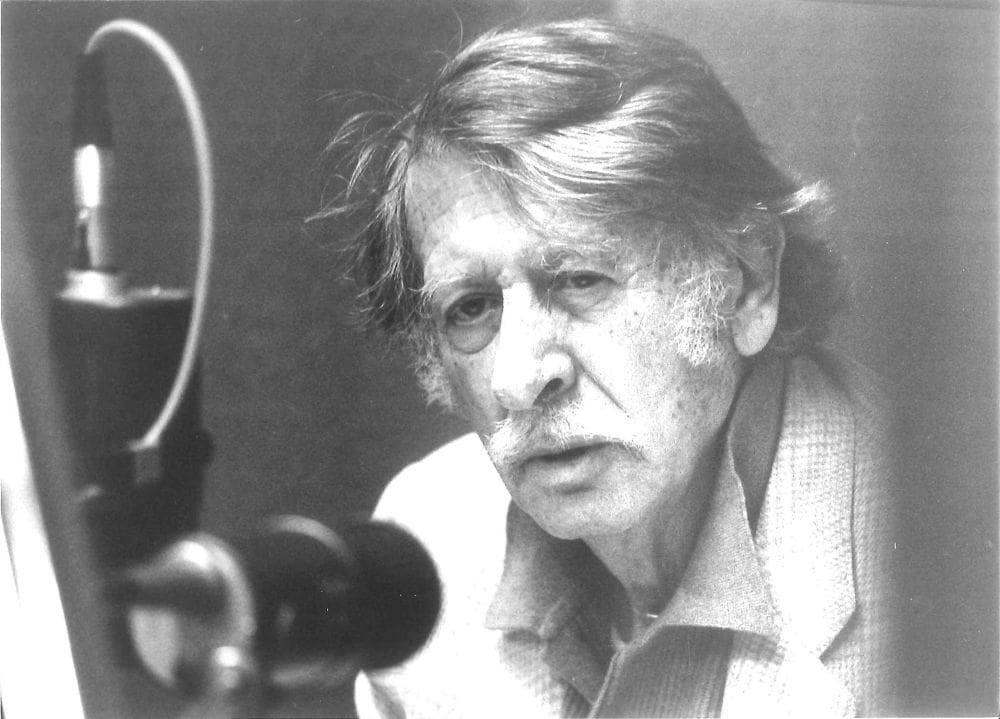

Of course, there were older writers too among the newcomers, and the youngest ones tended to be somewhat over twenty. Forty-two-year-old Victor (Győző) Határ, the modernist poet and writer joined the BBC‘s Hungarian Section, where he became a kind of rival to Cs. Szabó, as his regular book-reviews were often polished up to brilliant radio-essays, but even more so through his translations of classical Passion plays. Up to then, Cs. Szabó used to be the Section’s own playwright on festive occasions.

As far as the literary magazines were concerned, they soon began to multiply.

Látóhatár (renamed in 1958 as Új Látóhatár), which existed since 1950, started life anew under the joint editorship of Gyula Borbándi, Radio Free Europe’s cultural editor and the poet Gábor Bikich. Borbándi was given a free hand to publish in the magazine whatever went out on air in his art programmes.

While Új Látóhatár was a monthly publication, in London (with the financial help of the Congress for Cultural Freedom, an anti-Moscow organisation) a group of writers (including reform-Communists, veteran socialists and non-partisan Hungarian patriots) started the broadsheet-format bi-weekly newspaper Irodalmi Újság (Literary Gazette). It was edited by two 1956 emigrants: the poet György Faludy, whose book My Happy Days in Hell (1962) made a big splash, telling about his ordeals at the infamous Recsk hard labour camp, where Hungary’s Communist regime imprisoned its critics (raging from Socialist politicians to union leaders and priests), and writer-publicist György Pálóczi-Horváth, who in 1947 returned to Budapest from London, after joining the effort to extract Hungary from the wartime coalition with Hitler’s Germany, and soon found himself in prison, accused of spying for Britain. The editorial board also included László Cs. Szabó and Zoltán Szabó.

In 1962, the American-run Congress for Cultural Freedom withdrew its support from Irodalmi Újság and wanted to close it down. But Tibor Méray, a reform-Communist, who back in Budapest had worked for the paper when it changed from being a Muscovite party rag into one of the intellectual forerunners of the Revolution, would not put up with the Americans’ demand, and in Paris, where he lived, continued publishing Irodalmi Újság, often running into great financial difficulties.

László Cs. Szabó once told one of his BBC colleagues: ‘I send the script of my longer radio programmes, slightly re-edited, to be published by Új Látóhatár. The shorter ones I post to Rome, to Gellért Békés‘s Katolikus Szemle (Békés, himself a poet, was Professor of Dogmatics at the Vatican’s Ateneo di San Anselmo), and whenever I write a quick comment on something concerning cultural politics, I submit that to Irodalmi Újság.’

Eventually, the publishing choice widened even further. In 1962 young Hungarians living in France started Magyar Műhely (Hungarian Workshop), a tastefully printed magazine, aiming to further avant-garde literature; in 1980 Ferenc Mózsi the poet established Szivárvány (Rainbow) in Chicago, and a year later Washington potes brought out Arkánum, giving space to modernist tendencies.

Very few 1956 Hungarian refugee writers and poets (apart from those who were brought to the West as young children) fostered an ambition to change their language in order to become an organic part of their host countries’ contemporary literature. Examining some exceptional cases we find that

those who made an effort were usually assisted by capable native spouses.

György Ferdinandy (1935), as Georges Ferdinandy, started off on a French writing career already as a university student in Strasbourg. His short-story collection Ile sous l’eau (1960) won the Del Duca Prize and the Bronze Medal of the Académie Rhodanienne, his 1967 collection of poems Le seul jour de l’année was awarded with the Saint-Exupéry Prize. Appointed as Professor of Human Studies at the State University of Puerto Rico, he also tried writing in Spanish. However, eventually he returned to his native tongue, became a well-known writer in Hungary and recently moved to Budapest to live there.

Stephen Vizinczey (1933) settling and marrying in Montreal, used both his historical and sexual experience to write a bestseller, In Praise of Older Women (1965), which was sold in three million copies all over the world. He now lives in Britain and mastering the language publishes further novels, but perhaps the old magic is gone.

Ágota Kristóf (1935–2011) fled to Switzerland in 1956 with her husband and young child. Her first book in French (Le Grand Cahier, 1986) has been translated to twenty languages. She had learn French as an adult, and claimed that she never managed to learn it perfectly. The success of her story is due not least to the eerie, fragmented style in which it was written. She always used the present tense because she did not want to handle the complicated French past tenses. The short sentences, devoid of adjectives, convey the utter bareness of the world, as seen by her characters, a pair of twin boys.

It is noticeable however that the long years spent in various foreign countries, in a foreign intellectual ambiance, sometimes leave a mark on the output of those who began to publish their first works as emigrants, even if they chose to write in Hungarian.

Sándor András (1934), a writer of both poetry and prose, after a short spell at Oxford University continued his studies in California and in 1966 he won the Új Látóhatár short-story competition with a pieces evidently influenced by contemporary American beat writing.

Tibor Papp (1936), co-editor of Magyar Műhely in Paris, wrote some sound poems resembling similar experiments produced by the French avant-garde. The soberness of English story-telling prose, the examples of say Graham Greene or Ernest Hemingway, made me, a long-time resident of London, to develop a writing style, modern and easy flowing, but all in all free of the linguistic firework exercised by the best French exponents of the métier Boris Vian or Queneau.

Before the war Zoltán Szabó used to enjoy attending the regular gatherings at the ‘writers’ tables’ in various Budapest cafés. With a sizeable group of young talents suddenly turning up in London, he thought it a prolific idea to set up a similar gathering point in South Kensington’s Café Hades, near his house. It became a lively discussion circle where for example historian László Péter (later Professor of History at London University) could argue vehemently, trying to refute the precepts of Miklós Krassó, the neo-Marxist philosopher.

It was the idea of two pre-1956 Hungarian emigrants living in Holland, Miklós Tóth and Áron Kibédi Varga (Professor of French Literature at Amsterdam University)

to turn a Calvinist summer camp into a regular Hungarian Study Week,

open to all age-groups and all faiths within the emigrant diaspora (with an emphasis on the younger generation). Following the first meeting in 1958 at Doorn, the study weeks, named after Kelemen Mikes, an 18th century emigrant essayist, gained more and more support, providing an ideal opportunity for Hungarian intellectuals in Europe to meet one another and to enjoy the talks given by a top selection of emigrant scholars. Towards the end of the 1970s the organisers found it possible to invite lecturers and guests from Hungary as well. The programme always included a candle-lit evening of writers and poets reading from their own works.

The Dutch example was followed by other Hungarian associations, Catholic Pax Romana and the European Protestant Free University, which, apart from organising similar meetings, began to publish, and and in 1984 brought out the collected essays of the most revered Hungarian political thinker, István Bibó, who was sentenced to life imprisonment after the Revolution and was only released in 1963 with amnesty.

Both Magyar Műhely and Szivárvány set up their respective publishing wings, while the newly formed, London-based Hungarian Writers’ Association Abroad started to bring out an ambitious series of books: anthologies of poetry, novels and essay-collections. One of the first volumes of the series was a selection of short stories by Tibor Déry, imprisoned in Hungary for turning against the Muscovite dictatorship despite being a veteran Communist Party member.

In London Lóránt Czigány, a literary historian and his friend the poet István Siklós came to the conclusion that the Café Hades was not the ideal venue to hold larger meetings and some kind of club should be set up, perhaps even livelier and more open than the Kelemen Mikes Circle or the Austrian Bornemissza Society. Their declared aim was to ‘foster Hungarian culture abroad’. When asked, László Cs. Szabó was of the opinion that literature and cultural history should be the central themes in the association’s programme. The Szepsi Csombor Circle, named after the Hungarian scholar who travelled around Europe including Britain, and published an amusing travelogue about his experiences in 1620 (Europica varietas), organised its monthly meetings from 1965 onwards,

using the hospitality of Hungary’s friends, the Poles, who always found available space in their huge central club,

the Polish Hearth. The Poles were willing to let the Circle use the main meeting hall of the house, when in 1980 the British Council invited Hungary’s best poets to London (Gyula Illyés who had a very successful solo appearance there in 1967 was ill at the time) and it has agreed to their taking part in an evening of poetry-reading under the auspices of the emigrant group. Sándor Weöres, János Pilinszky, Ágnes Nemes Nagy, István Vas, Ferenc Juhász and Amy Károlyi were the participants, the hall was filled to the brim, and dozens of people had to listen from the corridor, through the open doors.

The emigrant writers made it their important task to use their postural potentials for letting the world recognise the excellence of Hungarian literature. Lóránt Czigány toiled for years on producing The Oxford History of Hungarian Literature (published in 1984). It is a useful reference work, but critics found it somewhat too scholarly. More importantly, Paris-based László Gara, a friend of many leading French poets of the age, managed to put together an excellent Anthologie de la poésie hongroise du XIIe siècle à nos jours in 1962, with Hungarian emigrants providing the rough translations. It was Gara’s untiring effort that provided a shining example for Paul Tábori in London and Tamás Kabdebó in Ireland to begin working on a similar anthology in English. Their task was more difficult because the English poets asked to take part were first reluctant to translate. The literary translation of poetry from a strange language, using roughs, had no tradition in England. For a while it seemed that the effort will falter. When all looked lost, Ádám Makkai (who was the first 1956 refugee student of Harvard University), later Professor of Linguistics at the University of Illinois, himself a multilingual Hungarian poet, came to the rescue, and in 1996 a more than 950 pages anthology, In Quest of the Miracle Stag has been completed. By then it could be jointly published by Chicago and Budapest sponsors.

By the 1980s the loosening-up process was at an advanced stage within the East- European so-called Socialist Camp and the Soviet Empire soon fell apart. Hungary’s Kádár regime lived on for thirty-three years from 1956 with Soviet assistance, but in 1989 it came to the point of a natural collapse. After free elections democracy returned to the country, and Hungary did not need to have emigrants. The literary magazines of the Western diaspora closed down with the quiet satisfaction that they had fulfilled the task that was expected from them:

keeping the flame of 1956 alive and helping a generation of writer to remain faithful to their mother tongue.

Sadly, neither Zoltán Szabó nor László Cs. Szabó (among many other leading intellectuals) lived long enough to see the day. Notably, relatively few of the surviving 1956 refugees repatriated to Hungary; after all, it is easy now to commute and writers can publish their works wherever they want to. The best works born in exile were re-published in Hungary, enriching the old country’s literary heritage.