The following is the third and last instalment of a three-part paper[1]. (Editor’s note: For the sake of coherence, the introduction and the conclusion of the analysis are published at the start and at the end respectively of each instalment.)

History did not end after the fall of the bipolar world order in 1990. The ‘West’ failed to take advantage of the historical situation to homogenize the world in its own image and soon the polarization of the world began/continued.

Certain actors started to ask for, if not demand, a leadership role, if not global, at least regional, something the ‘West’ had never granted them, on the contrary, it had made them its targets. As a result, on the geostrategic map of the Old World, a great chessboard, many ‘pieces’ have been given or have won roles and opportunities that they have begun to take advantage of in recent decades. The Western euphoria soon dissipated as it had to face the cultural and religious diversity of the world. Many cultural and religious divergences and the resulting diverging trends have succeeded in breaking the coveted coherence. The ‘West’ has not noticed or understood this—it is, therefore, surprised to see that other regions of the world, other global or regional powers, following different development paths, are succeeding economically and politically and are slowly

building an alternative reality to the ‘West’.

The ‘West’ has realized that if it plays the chess game with the current distribution of chess pawns, according to the traditional rules of chess, it will be checkmated in a few moves. The following paper will examine the challenges and even the breaking points that threaten the global influence and engagement of the ‘West’, including the EU, and that could have far-reaching consequences for the future of the ‘West’, and for Western values itself.

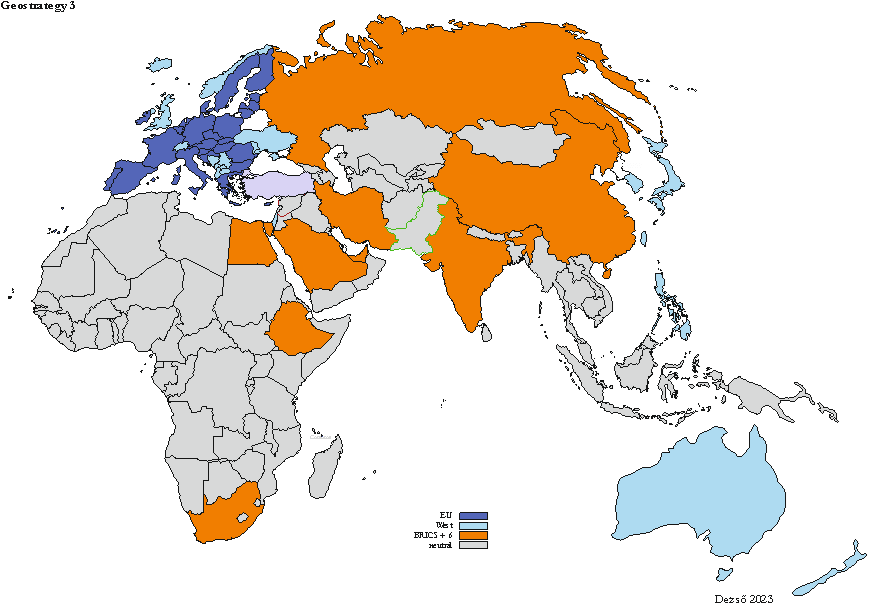

In the last two years, two wars have shaken the world, or at least the global public, which have extremely, if not permanently, divided the world, and accelerated the emergence of two great camps: the ‘West’ and the ‘East’. In addition, the expansion of a new world trade and economic platform and network, the Alliance of the BRICS countries, is now having a major impact on the coherence of the world, which had hitherto been dominated by the ‘West’. The present paper aims to illustrate the three fault lines that are about to redraw the map of the global geostrategic balances of the Old World.

***

The BRICS Countries

Founded on 16 June 2009 (BRIC) and enlarged on 24 December 2010 to include South Africa, BRICS is a system of cooperation between three large and two emerging economies, which has evolved from an initial economic/trade cooperation to a common geopolitical factor. BRICS is seen by many as a rival to the G7 forum (France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the UK, the US, and Canada). The BRICS countries, which are seeking to challenge Western economic hegemony, are neutral regarding the Russian–Ukrainian conflict and may be interested in creating at least a bipolar world order to replace Western hegemony and the unipolar world order. They are joined by emerging centres of power outside the Western global economic and political canon, which have never been acknowledged as such in history by the ‘West’ but have rather often been the targets for Western expansion. Such countries may be Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Egypt, which are vying for the status of core countries of the (Sunni) Muslim world. Turkey, as a NATO member state, can not join the BRICS countries of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, but beside Argentina, five countries will soon become part of the group from 1 January 2024; countries that could play a key role in determining the future political and economic orientation of the Middle East and Africa: Iran, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, and Ethiopia. This new alliance could be strong enough[2], due to its very existence and its developmental directions, to be a warning to the ‘West’ (including the EU) that its hegemony and leadership are on the wane.

As shown in Figure 3 below, the G7 share of world GDP is 29.93 per cent; the share of the EU with its 27 Member States is only 13.56 per cent, while the BRICS share is currently 32.17 per cent before enlargement and will be 36.9 per cent after enlargement on 1 January 2024. Thus, it can clearly be seen that in terms of GDP per economic community (G7, BRICS+6), BRICS+6 will outperform the G7, the leading economy of the ‘West’.

| G7 | EU | BRICS | |||

| % of World[3] | % of World[4] | % of World[5] | |||

| Canada | 1.36 | Austria | 0.36 | Brasil | 2.35 |

| France | 2.21 | Belgium | 0.44 | Russia | 2.89 |

| Germany | 3.17 | Bulgaria | 0.12 | India | 7.51 |

| Italy | 1.83 | Croatia | 0.09 | China | 18.82 |

| Japan | 3.72 | Cyprus | 0.03 | South-Africa | 0.57 |

| UK | 2.22 | Czech Rep. | 0.31 | 32.17 | |

| USA | 15.42 | Denmark | 0.25 | Iran | 0.99 |

| Estonia | 0.04 | Saudi Arabia | 1.29 | ||

| Finland | 0.19 | UAE | 0.51 | ||

| France | 2.21 | Egypt | 1.03 | ||

| Germany | 3.17 | Ethiopia | 0.23 | ||

| Greece | 0.24 | Argentina | 0.71 | ||

| Hungary | 0.24 | ||||

| Ireland | 0.41 | ||||

| Italy | 1.83 | ||||

| Latvia | 0.04 | ||||

| Lithuania | 0.08 | ||||

| Luxembourg | 0.05 | ||||

| Malta | 0.02 | ||||

| Netherlands | 0.74 | ||||

| Poland | 0.98 | ||||

| Portugal | 0.27 | ||||

| Romania | 0.45 | ||||

| Slovak Rep. | 0.13 | ||||

| Slovenia | 0.06 | ||||

| Spain | 1.38 | ||||

| Sweden | 0.41 | ||||

| 29.93 % | 13,56 % | 36.90 % | |||

As Figure 4 below shows, 8.14 per cent of the world’s population lives in the G7, 5.54 per cent in the 27 Member States of the EU, and no less than 46.15 per cent, almost half of the population, lives in the BRICS+6.

| G7 | EU | BRICS | |||

| Country | Population | Country | Population | Country | Population |

| Canada | 38,704 | Austria | 9,081 | Brasil | 216,642 |

| France | 65,745 | Belgium | 11,699 | Russia | 145,629 |

| Germany | 83,775 | Bulgaria | 6,792 | India | 1,419,656 |

| Italy | 60,148 | Croatia | 4,038 | China | 1,452,128 |

| Japan | 125,081 | Cyprus | 1,231 | South-Africa | 61,453 |

| UK | 68,766 | Czech Rep. | 10,746 | 3,295,508 | |

| USA | 336,679 | Denmark | 5,857 | Iran | 86,976 |

| 653,817 | Estonia | 1,317 | Saudi Arabia | 36,329 | |

| Finland | 5,561 | UAE | 10,165 | ||

| France | 65,745 | Egypt | 108,032 | ||

| Germany | 83,775 | Ethiopia | 123,771 | ||

| Greece | 10,262 | Argentina | 46,409 | ||

| Hungary | 9,577 | 3,707,190 | |||

| Ireland | 5,052 | ||||

| Italy | 60,148 | ||||

| Latvia | 1,832 | ||||

| Lithuania | 2,637 | ||||

| Luxembourg | 649 | ||||

| Malta | 445 | ||||

| Netherlands | 17,249 | ||||

| Poland | 37,674 | ||||

| Portugal | 10,114 | ||||

| Romania | 18,944 | ||||

| Slovak Rep. | 5,458 | ||||

| Slovenia | 2,077 | ||||

| Spain | 46,679 | ||||

| Sweden | 10,276 | ||||

| 444,915 | |||||

| % of World[6] | 8.14 % | 5.54 % | 46.15 % | ||

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, Middle Variant, World Population Prospects 2019, File POP/1-1: Total population (both sexes combined) by region, subregion and country, annually for 1950-2100 (thousand).

Although the BRICS group was not officially defined as an antipode or rival to the ‘West’/G7/EU at the time of its creation, the sanctions policy of the Russo–Ukrainian war and the West’s break with Russia and its policy of disengagement from China have completely reinterpreted the earlier reading of BRICS’ goals. With its enlargement on 1 January 2024, BRICS has gained strategic allies and key positions (Strait of Hormuz, Suez Canal, etc.) in the Muslim world, even vis-à-vis the ‘West’. The author of this article dares to state this so explicitly because it has been reported that the BRICS+6 alliance is planning to put on the agenda the creation of a common currency to rival the US dollar in world trade. Since the US dollar dominates world trade[7] and a significant part of the savings of individual states is also in dollars,

any threat to global Western economic hegemony, and specifically to the USD’s monopoly, is tantamount to a declaration of war.

The global hegemony of the dollar is one of the most important bases, if not the most important one, for the economic supremacy of the ‘West’, but it is also its Achilles’ heel because the greatest threat to the ‘West’ is not so much military as economic: a shift in world GDP shares to the detriment of the ‘West’, or a breakdown in the dollar’s monopoly, which could lead to a serious loss of confidence in the capital markets and then to a collapse. Since BRICS+6 could also be the loser in such a collapse, it will have to create a new common currency to replace the dollar, which could even take over the role of the US currency, either partially or gradually.

This situation is indirectly the result of the attitude of the ‘West’.

Conclusion

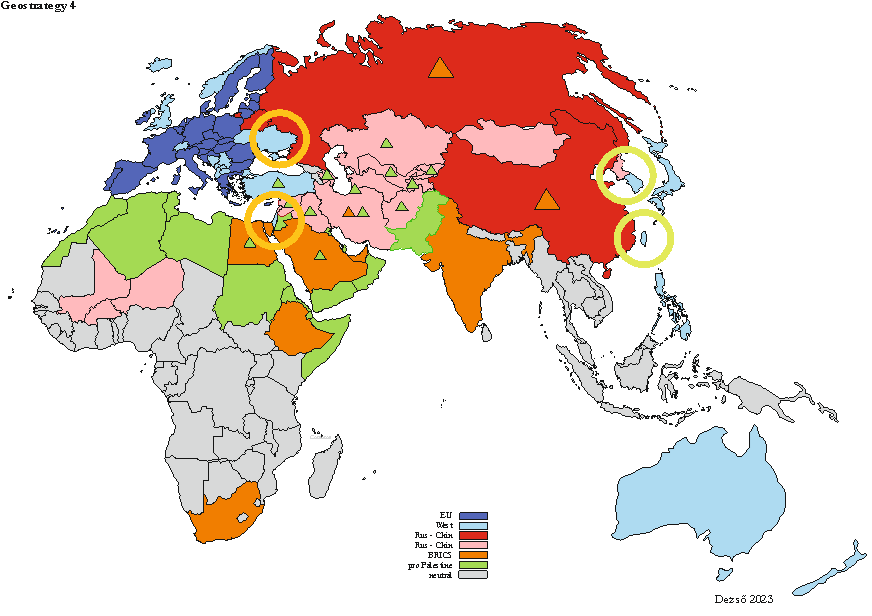

The fault line described above and in the previous two parts of this series of articles carries with it the danger of the Western and the EU elites, which are largely unaware of the many directions of development in the world, becoming increasingly isolated. A geostrategic environment is developing around us which, as Map 4 shows, is slowly bringing the ‘West’, especially Europe’s neighbours and rivals, onto a common platform, along different principles and interests.

In such a geostrategic context, the current EU leadership seems to be oblivious to, or deliberately ignores, the threats to the future of the EU and the Western world, and pushes themes, such as gender ideology and open society, that are largely symbolic, distracting attention from the real hazards and weakening the EU from within rather than strengthening and enhancing its internal coherence.

The EU—at the latest in light of the mass pro-Palestinian demonstrations in Europe after the Hamas terrorist attack (see above)—must finally realize that uncontrolled immigration is not the solution, but the problem itself, since, contrary to the expectations of Western elites, it has not had the ‘fertilizing effect’ on the economy or society. On the other hand, the unwanted processes that inevitably accompany the arrival of large numbers of immigrants from other cultures and backgrounds occur daily, whether along Hungary’s southern borders or on the streets of Western Europe. The greatest danger of all is the security threat posed by Islamic terrorism. The pro-Palestinian demonstrations, for example, raise the question of whether the Muslim population in Europe can distance itself from the Islamic radicalism of Islamic terrorism, conflated with the liberation ideology of Hamas.

The Russo–Ukrainian war is the most pointless undertaking from the point of view of the EU’s geostrategic interests. It is the bloodiest armed conflict since the Iraq–Iran war, with at least half a million (500,000) victims, the same number of crippled families, seven million refugees, and a partly destroyed country indebted for at least 50 years. Looking at the current and potential crisis zones, from a strictly geostrategic point of view,

the Russian–Ukrainian front, with its symbolic messages, is the most meaningless and bloodiest conflict that is not in the interest of the ‘West’.

Apart from the crippling of Ukraine, it is the EU economy that has suffered the most (petrol prices out of control, inflation, the consequences of the loss of cheap energy for the private and industrial sectors, a dramatic deterioration in the EU’s economic competitiveness, and the list goes on). In addition, the ‘West’, including the EU, has taken on financial burdens that are putting a strain on its budget. Moreover, Western strategic ammunition stocks and arms production have come under unprecedented pressure, posing a substantial threat to the security of the ‘West’. It must also be alert to other crisis hotspots (Israel) and avoid any escalation, as it is probably unprepared for challenges of this scale. If the two other crisis hotspots in the Far East (Korean Peninsula and Taiwan), where there is a threat of a military conflict, were to erupt as well, the ‘West’ would be faced with an almost insurmountable problem from a geostrategic and military point of view. At the same time, it can also be said that for some time now the EU has been the most rapidly arming political community.

In summary, the geostrategic environment around the EU and Europe, partly as a result of the EU’s deliberate decision (breaking with Russia), partly through no fault of its own (the Palestinian issue), and its attitude of only observing the changes in the global economic environment from afar, without being able to influence them in any meaningful way (BRICS+6), has reached a situation that risks isolation.

From the point of view of maintaining the current form and values of the ‘West’, the continuation of a migration policy is life-threatening, because it is triggering internal processes in the Western world which, willy-nilly, will result in the sacrificing the core values of the ‘West’ on the altar of the progressive philosophy of inclusion, and in the weakening from within of its geostrategic position the losing of which could have fatal consequences in a world where the axis of global economic development, population growth, and history no longer revolve around Europe.

Europe and the European Union no longer sit at the global geostrategic chessboard as players,

but are at best kibitzers, even if the EU leadership refuses to acknowledge this.

If the ‘West’, of which this author is an integral and committed part, does not change its present policy, it will soon find itself in a geostrategically hopeless situation.

[1] This paper is part of a larger comprehensive geostrategic study by the author. As it stands, it raises more questions than answers, but its basic premises allow clear geostrategic conclusions to be drawn.

[2] Globally, 42 per cent of oil production will be in the BRICS countries.

[3] GDP based on PPP, share of world, IMF, https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/PPPSH@WEO/EU/CHN/USA.

[4] GDP based on PPP, share of world, IMF, https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/PPPSH@WEO/EU/CHN/USA.

[5] GDP based on PPP, share of world, IMF, https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/PPPSH@WEO/EU/CHN/USA.

[6] World population in 2023: 8,031,800,000 people. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, Middle Variant, World Population Prospects 2019, File POP/1-1: Total population (both sexes combined) by region, subregion and country, annually for 1950-2100 (thousands), POP/DB/WPP/Rev.2019/POP/F01-1: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/.

[7] ‘The USD was involved in nearly 90 per cent of global FX transactions, making it the single most traded currency in the FX market. The dominance of the USD is evident across all FX instruments and counterparties. At least 85 per cent of trading in the spot, forward, and swap markets features the USD in one leg of the transactions,’ Maronoti Bafundi, ‘Revisiting the international role of the US dollar’, BIS Quarterly Review, 5 December 2022, Bank for International Settlements, https://www.bis.org/publ/qtrpdf/r_qt2212x.htm.

Read Part I and Part II: