Until recent decades, King Andrew II (r. 1205–1235) was regarded as one of the most unfortunate rulers in medieval Hungarian history—some even called him the ‘operetta king’. If they tried to find something positive in him, they mostly pointed to the fact that he was the father of Saint Elizabeth and was forced to issue the Hungarian ‘Magna Carta’, the so-called Golden Bull of 1222. The assessment of his Crusade has also been contradictory to this day: was it a serious campaign or just an improvisation?[1]

The Fifth Crusade (1217—1221) was one of the most exceptionally well-organized of all.

One of the cleverest popes of the Middle Ages, Pope Innocent III learned from the mistakes of the Fourth Crusade. The campaign, planned to last three years, was already announced in 1215, for which the financial backing was provided by taxing the priests’ income.[2] At the beginning of 1217, the Pope was among the first to remind the monarchs of their inherited duty, along with the King of England and Andrew II, and, simultaneously, he placed Hungary under papal protection, as a vow to start a crusade had already been made by Andrew’s father, King Béla III, around 1192.

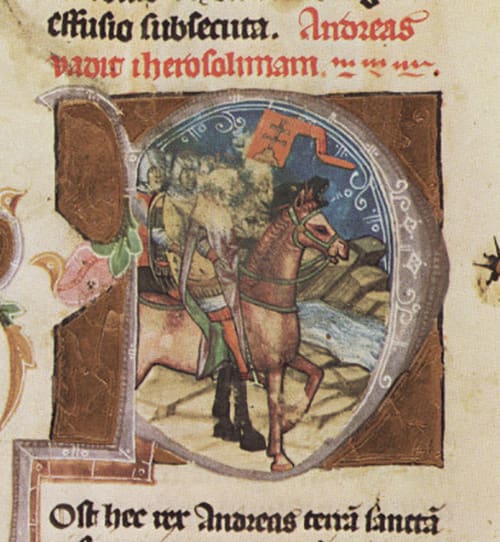

In the late summer of 1217, the royal army marched south from the sacral centre of the country, Székesfehérvár. In Zagreb, the King attended the rededication of the cathedral founded by King Saint Ladislaus around 1094, and from there he marched to the seacoast to Split, where he arrived on 23 August and immediately attended mass in the Cathedral of Saint Domnius.[3]

The Hungarian–Austrian army of perhaps three or four thousand assembled there was considered by contemporaries to be quite considerable, even if it fell short of an army of ten thousand mentioned in the sources. The ships hired from Venice, which had been waiting in Split since July, left sometime in September, and arrived at their destination, Acre (known locally as Akko), after a voyage of about twenty days. In Acre, the most important city in the Holy Land since the loss of Jerusalem in 1187, the first council of war was held between the Grand Masters of the Knights and the other Crusader leaders. Although Andrew was the only European king to appear in person, the real leader was John of Brienne, King of Jerusalem.[4]

However, for a long time, King Andrew had the largest crusading army, as the Frisians, the Rhinelanders, and the English, though outnumbered his troops, did not arrive in time because they stopped on their way to fight the Muslims of Hispania. Some of them stayed in Santiago de Compostela in Spain, while others joined the Portuguese Reconquista near Lisbon. Although their first troops left in mid-1217, it was not until late April 1218 that they arrived at Acre. Despite that, the Hungarian and Austrian rulers began military operations without them.

According to contemporary Arab sources,

the Hungarian King personally participated in the first phase of the operations.

They boldly went straight against the famous general Saladin’s brother, the Egyptian and Syrian Sultan Al-Adil (r. 1200–1218), who was visibly surprised by the unexpected attack. They tried to force the Sultan into battle south of the Sea of Galilee, but he retreated instead. After setting out on 4 November, they reconnoitred the area around Mount Tabor (Har Tavor), crossing the Jordan River near the Sea of Galilee. In the meantime, they had not only plundered Beisan for a rich booty (today’s Beit She’an) but had also fulfilled their vow of bathing in the Jordan and visiting holy sites.

The army also ventured into the 1,500 square kilometres of The Golan Heights and the Hauran Plain to the east of it, most famously at Banias, at the foot of Mount Hermon, also known from the Gospels, where the Banias River, which feeds the Jordan, originates. Sultan Al-Adil retreated as far as Damascus, and even sent his family further afield, to what is now Bosra (Busra al-Sham) in Syria. In any case, the Crusaders did not follow him but went back to Acre.

After a short rest in Acre, the actual military actions continued with an attack on Mount Tabor. The papal court was also concerned about the Arab fortifications erected after 1212 and was aware of the difference of opinion between Al-Adil and his son Al-Mu’aẓẓam on the establishment of the fortress of Tabor. As the eventual outcome of events showed, the papal plan to exploit the conflict between the Sultan and his son was not unfounded. The huge fortress was built on a prominent, 600-metre-high rocky plateau, defended by 77 towers and a garrison of nearly 2,000 men. It was strategically important, controlling the routes from Acre to the Sea of Galilee.

According to the Arab chronicler Abū Shāma, during the attack on Mount Tabor in December, the Crusaders managed to find a hidden path to the castle. However, the attackers failed to take advantage of the initial surprise. They used siege engines, but the defenders set them on fire. The Crusaders retreated, but within a few years, the castle was finally voluntarily abandoned and emptied by the Muslims, who did not consider it defensible in the long term.

In contrast to the local leaders, who were well aware of the unpredictability of the fighting in the Holy Land, there was also a hot-headed, adventurous core among the Crusaders. It could have been their action to attack the castle of Beaufort (Qal’at al-Shaqif) in mid-December with half a thousand horsemen through Mount Lebanon. However, in the damp weather, the local Arabs had no difficulty in surprising the horsemen in the mountains as they made their way to Mashgara in the Beqaa Valley in southern Lebanon, forcing them to turn back with heavy losses.

The Hungarian King was criticized already by his contemporaries for leaving with his troops after a few months, although he was not the only leader to leave prematurely. In fact, in what was nearly half a year,

the Hungarians had gained sufficient combat experience to realize that the military force at their disposal was insufficient to launch a decisive operation.

They also knew that the main objective of the Crusade would be to attack Egypt, which implied a presence of several years. If anything, the losses suffered during the winter of 1217–1218, the King’s illness, and the uncertain domestic political situation in Hungary only further strengthened Andrew’s resolution to bring his army home as soon as possible. It is not known whether the King took sufficient cash and precious metals with him, nor whether he managed to obtain loans locally. In any case, they took with them the crown of the first Hungarian Queen, Gisela (d. 1065), wife of St Stephen, which they converted into money.

On his way home, Andrew II first visited the most important fortresses of the Knights Hospitallers, Krak des Chevaliers (Ḥiṣn al-Akrād) and Margat (Qal’at al-Marqab). During these visits, the King made several donations to the Hospitallers. Margat, near Baniyas in Syria, covering more than 15 hectares, is now famous for the excavation work carried out by archaeologists from Pázmány Péter Catholic University in Budapest since 2007, who have restored several beautiful fresco fragments in the castle chapel.

On the overland route home, the King of Hungary was conspicuously diplomatic. From Antioch, he followed the ancient Pilgrim’s Trail through Asia Minor, which led from the old Byzantine–Persian border to Constantinople, a distance of 1,700 kilometres. The overland route would have been perilous if the ruler of the Seljuq Turkish Sultanate of Rum, Kaykaus (Izz ad-Din Kaykaus, r. 1211–1220), had not maintained a balanced relationship with the Byzantines and the Latin Crusader states. Already before the Crusade, in Tarsus, Cilician Armenia, Prince Andrew had betrothed the daughter of Leo I, the Armenian King who had allied himself with the West, and later the Greek Emperor of Niacea, Theodore I Laskaris, betrothed his daughter Mary to King Andrew’s son, Béla (later King Béla IV of Hungary). There is nothing unusual in this, as similar acts already took place during the Second and Third Crusades, not to mention that these recent alliances also guaranteed the safety of the homeward journey. From Constantinople, the King travelled along the military road, the so-called ‘Via militaris’, which was a further 1,050 kilometres to the Hungarian border.

One of the greatest achievements of the campaign was that the Hungarian army took part in the battles of the Holy Land without major losses, and on the way home, the King was also able to fully supply his army and lead it home safely—at least we do not know of any losses. Of course, this can only be considered an achievement if the success of a campaign is not measured in terms of the number of heroic dead. Their participation in the campaign increased the security of the Crusader states, contributed to the later recovery of the fortress of Tabor, and paved the way for a later attack on Egypt, the procrastination of which was due not to Andrew II but to the delay of the Rhine–Friesian troops.

Nevertheless, posterity did not judge the participants by the same standards. The Austrian Prince was nicknamed ‘der Glorreiche’ (‘the Glorious’), while Andrew was at best called ‘the Jerusalemite’, which is, of course, an exaggeration since he never got to see the Holy City. Similarly, it is resented that the Hungarian King returned home laden with relics of saints, which he distributed among the high priests loyal to him. Yet all the rulers who had visited the East had done so. Later Hungarian tradition considered the relics of the Holy Innocents in the treasury of the Zagreb Cathedral, Protomartyr of St Stephen in Esztergom, St Margaret of Antioch in the Szepes Chapter (today’s Spišská Kapitula, Slovakia), and St Bartholomew in Pécs to be gifts of Andrew.

However, offering a positive assessment of the campaign does not mean we are breaking new ground either. French historian René Grousset was the first in the international literature to show an understanding of the Crusade of Andrew II and many more continue to do so today.[5] We do not regard the campaign as successful because it was Hungarian, but because

it was, in its time, a uniquely well-led, and, in our modern terms, ‘peace-making’ campaign with limited objectives.

In 2019, in Miliya in northern Israel—where, according to tradition, descendants of the Hungarian Crusaders live—, even a monument to King Andrew II was inaugurated on the anniversary of his Crusade.

[1] László Veszprémy, ‘The Crusade of Andrew II, King of Hungary, 1217–1218’, Jacobus, Vol. 13–14, 2002, pp. 87–110.

[2] James M. Powell, Anatomy of a Crusade, 1213–1221, Philadelphia, 1986, pp. 89–101.

[3] Thomas of Split archdeacon, History of the Bishops of Salona and Split, Olga Perić, Damir Karbić, Mirjana Mattjević Sokol, and James Ross Sweeney (eds. and trans.), Budapest – New York, 2006, pp. 158–159.

[4] Thomas W. Smith, ‘The Role of Pope Honorius III in the Fifth Crusade’, in E. J. Mylod, Guy Perry et al. (eds.), The Fifth Crusade in Context. The Crusading Movement in the Early Thirteenth Century, London – New York, 2017, pp. 15–26.

[5] René Grousset, ‘La Hongrie et la Syrie chrétienne au XIII. siècle’, Nouvelle Revue de Hongrie, Vol. 30, No. 56, 1937, pp. 232–237.; James Ross Sweeney, ‘Hungary in the Crusades, 1169–1218’, The International History Review,Vol. 3, 1981, pp. 467–481.

Related articles: