Most political science students will encounter the concept of ‘cohabitation’ around their second year, a term mainly used in textbooks to describe the political system in France. They learn that cohabitation occurs when the president and prime minister in semi-presidential countries are from different political parties, which usually leads to political tensions of all kinds; and then they learn that cohabitation rarely does happen after all.

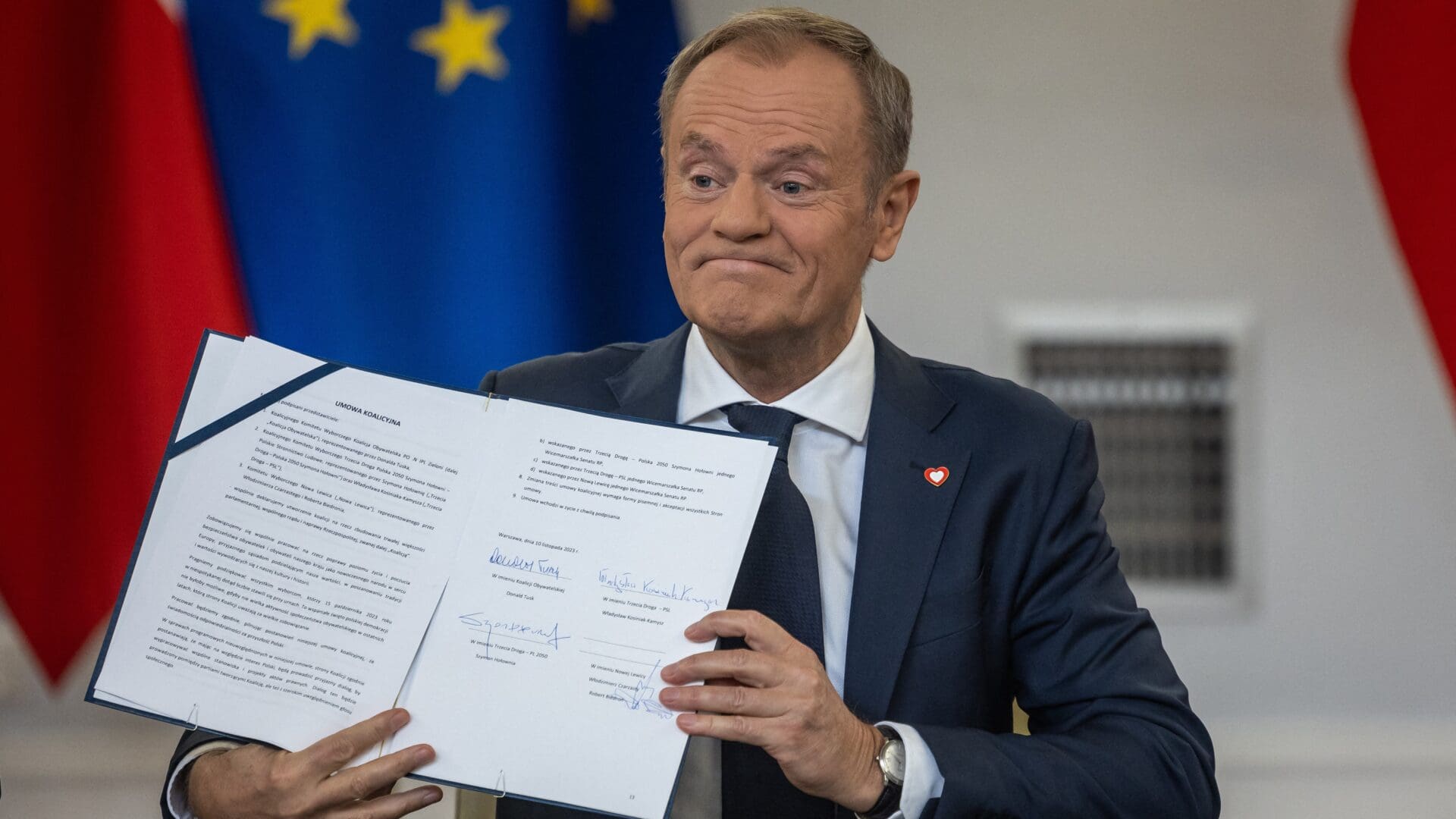

But not for Donald Tusk.

Tusk’s career in Poland’s big politics seems to be haunted by the looming shadow of cohabitation.

While Poland is not a semi-presidential country, it seems to work like one in practice, as presidents are usually much more involved in day-to-day political affairs than the framers of the constitution originally imagined. Donald Tusk and his Civic Platform (PO) party defeated the Kaczynski brothers’ Law and Justice (PiS) party in the 2007 parliamentary elections, but the contest was far from over, as the presidency of the republic was held by one of the main opponents, Lech Kaczynski. This period of cohabitation lasted until the tragic death of the president in 2010. And now it seems to be back.

The political preferences of Poland’s current president, Andrzej Duda, are hardly a mystery. Although his and Tusk’s political careers were intertwined at some point—they were both members of the now defunct Freedom Union party—, Andrzej Duda has been with PiS since the mid 2000’s. Duda has been serving as president since 2015, and, as could be expected, he did not rush to derail most of his party’s reforms, some of which were rather radical and controversial. However, this will most likely change once Tusk will be able to assume office as prime minister.

Despite the fact that it was Donald Tusk and his three-party electoral alliance that gathered the largest number of votes in the 2023 parliamentary elections, Duda, to the surprise of many, did not give Tusk the first mandate to start negotiations on forming a government. ‘I am the president, but Donald Tusk is not my candidate for prime minister,’ Duda declared recently, after mandating PiS’ Mateusz Morawiecki to start negotiations for forming a government.

But it is almost entirely unlikely that Morawiecki will succeed. PiS did not do well in this election, and although it will continue to hold the most mandates in the Sejm, the lower house of the Polish parliament, it still lacks the allies to form a majority needed for a government. Many parties in fact ruled out cooperation with the Kaczynski party well in advance.

Duda, however, insists that the party with the highest number of MPs in the Sejm should be the first to try to form a government. The president says the programme of the Tusk alliance, which includes centrist and left-wing powers as well as centre-right parties, is not convincing enough to break with tradition and give it the mandate to form a government first.

Given the relatively low chances of PiS success, the president’s move is more of a challenge to Tusk than a serious attempt to prevent his alliance from taking power. However, it is also a warning for Donald Tusk:

the next two years (Duda’s term expires in 2025) will certainly not be a period of frictionless coexistence.

The future prime minister is not in an easy position. His alliance, which at first glance seems more like an all-star anti-PiS selection of parties with very different ideological backgrounds, rather than a turnkey governing force, has not yet formally launched a coalition, and the process of forming a government is likely to be fraught with internal struggles. But things will not be much easier once they manage to agree on the composition of the future government. The Polish constitution allows for a presidential veto to be overridden if a governing coalition has enough seats in the Sejm, but the Tusk coalition does not have that many. In other words, if the new government seriously wants to change the key and divisive cardinal laws previously passed by PiS, it will almost certainly face a veto by Duda.

This also means that the new government is quite likely to not be able to deliver on many of its crucial election promises for some time (if they even decide to try and honour them, as many of the PiS reforms, which are controversial at international and especially EU level, have broad public support in Poland). This could also create legitimacy problems. And this is far from being the only difficulty: if the new government is unable to change the laws that led the EU to launch the Article 7 and the so-called rule of law proceedings against Poland, that could have serious economic consequences for the country.

The question is, of course, how the European Union and the Commission will act if there is indeed a real deadlock in Poland over these laws. Many in Brussels have been breathing a sigh of relief at the election results, which are expected to bring Poland back in line with the EU mainstream on a number of key issues. Tusk, who knows the EU well from the inside, is already seen by many in Brussels as a key Eastern ally, who could play a major role in balancing the newly emerging alliance between Hungary’s Orbán and Slovakia’s Fico, for example. However, these hopes—and the legitimacy of the rule of law proceedings—could easily be dented if the new Polish government fails to reverse PiS reforms, but EU scrutiny towards the country is nevertheless relaxed.

What is certain is that Donald Tusk will have to prepare for a multi-front struggle in the coming years, and how he tackles the first major challenge, the cohabitation with Duda, will certainly be telling.