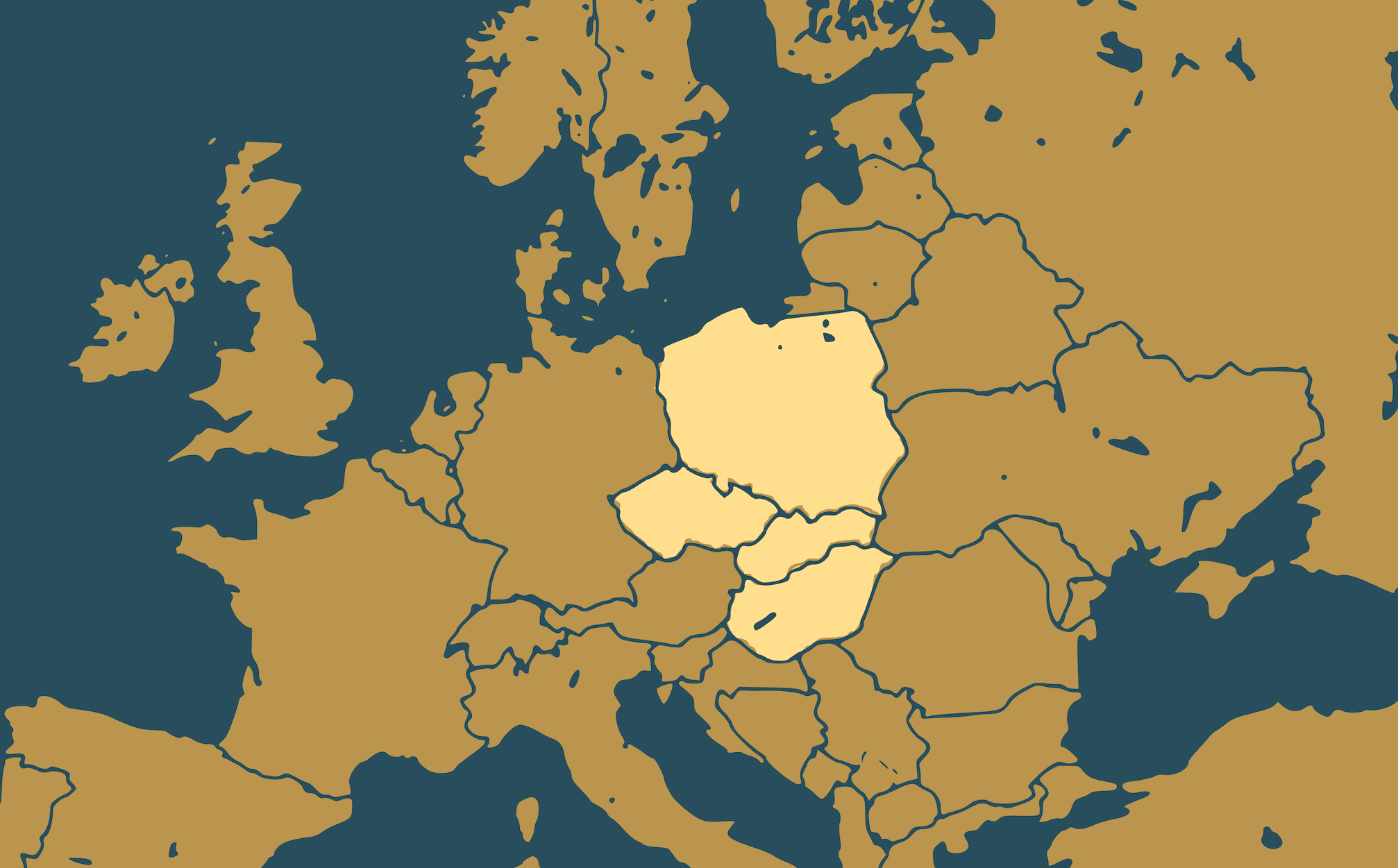

The Visegrád Four (V4) group, consisting of Poland, Czechia, Slovakia, and Hungary, celebrated the 30thanniversary of its existence last year. Back then, all V4-related news and conferences appreciatively discussed the “success story” of the V4 and how the Visegrád countries have become a symbol of effective regional cooperation within the EU. By no means were such remarks exaggerated. The alliance has not just achieved its primary goal, Euro-Atlantic integration, but it has been able to take cooperation to a further and deeper level, carrying out joint projects both independently and within the EU and NATO. The V4 countries have become the 5th largest economy in Europe combined and the 12th largest economy in the world, and are often referred to as Europe’s new economic engine, which could reach 80 per cent of the EU-15 group’s income level by 2030. But the most outstanding achievement of the ‘Visegrads’ is that they have been able to reconcile and formulate joint positions, amplifying their voice and increasing their influence within the EU on such main matters as migration or the EU budget.

As a result, despite the negative effects of Covid-19, V4 countries had high expectations regarding post-pandemic recovery and an optimistic vision of the prospect of their alliance when Hungary took over the annual presidency of the group in July 2021. But Russian aggression against Ukraine and the looming reality of war at the doorstep of the V4 has quickly undermined all positive attitudes and prospects and even cast doubt on the future existence of the cooperation.

The grave deterioration of relations is rooted in the lack of a joint position on the war

Different views on Russia have always been present among V4 countries, and these differences seem to be more pronounced now than ever before. While Hungary and Slovakia have always had a more moderate or even friendly stance on Russia, Poland and Czechia followed a more detached foreign policy when it came to Russian relations. The emergence of these two poles within the V4 is mostly related to the degree of dependence on Russian energy sources and how member states assessed Russia’s geopolitical ambitions in the past fifteen-twenty years. Now, the grave deterioration of relations is rooted in the lack of a joint position on the war, or, more precisely, on how to help Ukraine and force Russia to end the war at the same time.

The first major disagreement between V4 countries arose over arms shipments to Ukraine. Poland and Slovakia have shown great enthusiasm when it came to arms transfers to Ukraine, whilst Hungary has been more restrained in this matter. While Poland, as the leading advocate of arms shipments to Ukraine in the EU has transferred $7 billion worth of military equipment to its war-battered neighbour so far, including 200 T-72 battle tanks, MIG-29, and Su-27 fighter jets, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán tenaciously articulated that Hungary will not allow the transit of arms shipments from the territory of Hungary to Ukraine under any circumstances. The primary and most obvious reason for this difference in positions between the Government of Hungary and the other V4 countries is that although Hungary has started a major force development program in recent years, it still does not possess any significant spare capacity to export. As opposed to that, Slovakia, Czechia, and Poland have inherited a considerable heavy weapons production capacity from state socialist times, while the potential of the Hungarian defence industry is very limited, to say the least. Not to mention the almost 140 km long shared border between Hungary and Ukraine and the around 156,000 ethnic Hungarians living in Transcarpathia, both of which factors make the country consider its war-related decisions more cautiously, to avoid the spill-over of the conflict and to safeguard the security of the Hungarian minority in Ukraine. Nevertheless, Hungary has contributed to assistance measures within the framework of the European Peace Facility (EPF), which allows the EU to support the Ukrainian Armed Forces with personal protective equipment, first aid kits, and fuel, as well as military equipment worth €1.5 billion.

Dividing lines also seem to run deep in the V4 when it comes to Russian energy

Dividing lines also seem to run deep in the V4 when it comes to Russian energy. However, in this regard Hungary is not standing alone (even if the media often tries to portray it that way). Hungary, Czechia, and Slovakia, as landlocked countries and all linked to the massive Russian-operated Druzhba pipeline, rejected the approval of EU’s sixth sanction package which aims to phase out all Russian crude oil in six months and all refined oil products by the end of the year. These countries not just heavily rely on Russian oil imports (Slovakia 78 per cent, Hungary 45 per cent, Czechia 29 per cent of all supplies) but their refinery infrastructure also works exclusively with the Russian Urals Blend, which also requires time and hundreds of millions in investments to be switched to Western blends. While Poland is also highly dependent on Russian crude imports (68 per cent), those constitute only 24 per cent of the country’s energy mix; furthermore, it is the only V4 country that has access to the Baltic Sea and the LNG terminal on its shore. That is why Poland could propose its radical plan to become independent of Russian oil and gas by the end of the year (!), while Hungary, Czechia, and Slovakia had to get into a fierce debate within the EU to secure temporary exemption from the bloc’s Russian oil ban.

Spectacular indicators of the deteriorating relations between Visegrád countries were such events as the failed meeting of the V4 Defence Ministers in March, or the repeated, overt criticism of the Hungarian approach to the war by Polish Law and Justice governing party leader Jarosław Kaczyński, otherwise considered one of Viktor Orbán’s main European allies. The recent V4 Chiefs of Staff meeting that took place earlier this week in Hungary and where the future of military cooperation was discussed may represent a glimmer of hope that relations will improve, even though no one from Poland attended the event.

Although the Visegrád Four may be facing one of the most severe disruptions of its history, it is too early to discount it as a “collateral victim of the war”. Since the cooperation’s main virtue has always been its ability to overcome momentary political disputes, good relations can be restored if members can continue to focus on and identify specific areas they agree on. But of course, it will require time and patience, and, most importantly, well-adjusted government communications.