The following is a translation of an article written by Ákos Győrffy, originally published in Magyar Krónika.

Two hundred and eleven years ago today, Hungarian poet, literary critic, orator, and politician Ferenc Kölcsey finished the poem that reminds us Hungarians every time we sing it that we belong together in our hearts.

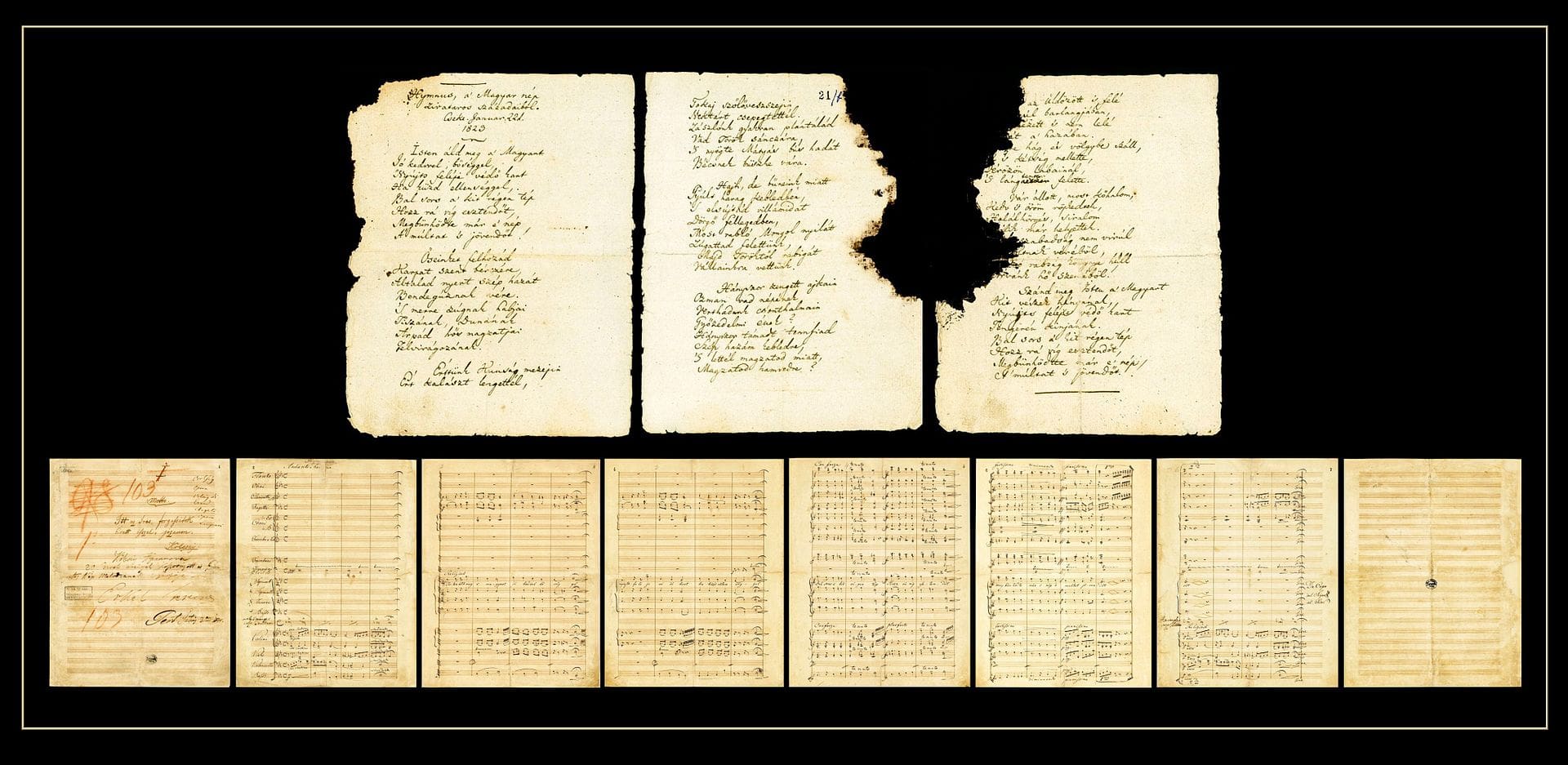

Two hundred and one years ago, on 22 January 1823, Ferenc Kölcsey completed his poem ‘Hymn, from the Stormy Centuries of the Hungarian Nation’. It was first published in the journal Aurora in December 1828, only almost six years later. On that January day, Kölcsey probably did not think that the poem he had just finished would one day become the official anthem of Hungary. If he had known in advance, he might not even have written it. It is a good thing he did not foresee it—it is not good for a poem to be written with any premeditation. A great poem, it is said, is torn from its author, created unexpectedly, without any premonition.

Let us imagine that probably wintry, gloomy January day in the village of Szatmárcseke. The manuscript of the hymn is pretty much finished, all that is left is to clarify and make minor corrections. Kölcsey is sitting in his study, with the fire crackling in the fireplace, the world outside is frozen, only the church bell, the bellow of the cows and the neigh of the horses from the stables behind the manor house can be heard occasionally. He reads the manuscript carefully, crosses out a word here and there, writes another over it, and then copies the whole text onto a clean, blank piece of paper. It is finished—nothing more can be taken away or added. A secretive, mystical moment. Something is born and embodied on paper.

Kölcsey’s biography is testament to the spiritual and intellectual crises he experienced during his short life. The ups and downs were followed by sparkling periods full of creativity and the light of the spirit. The brightest star of one of these brilliant and, in today’s terms, incomparably creative periods was his poem ‘Hymn’, which is known today by all people who profess to be Hungarian.

There are few poems that have made such impact in the otherwise dazzlingly rich Hungarian literature.

Perhaps only famous Hungarian poet and dramatist Mihály Vörösmarty’s ‘Appeal’ can match it. However, for the hymn to become a national anthem it would not have been enough for Kölcsey to merely ‘write’ it and then publish it in his first book of poems. If it had been so, no one but a few literary lovers would only know of it today. Composer, conductor, and pianist Ferenc Erkel, who set Kölcsey’s poem to music in an almost novelistic manner, has unfading merits in the fact that this was not its fate.

In 1844, the National Theatre launched a competition for the composition of the National Anthem. András Bartay, the theatre’s director, met Ferenc Erkel by chance on the street in the capital and persuaded him to submit an entry. After inviting him to his home and talking him into it, the following happened—and here I give the floor to Erkel himself, who recounted this scene four decades later:

‘…he pushed me into the side room, where a battered yellowish piano stood. He put a staff paper and the text of the poem before me and said, ‘Do it right away.’ I answered, ‘But brother, don’t be foolish! It’s no rolling a cigar that can be done right away…’ But he insisted that ‘it must be done.’ ‘No, it’s too late,’ I said, but instead of answering, Bartay…stepped out of the door, and locked it behind him. All I heard was him saying ‘Your humble servant!’ I am just standing there like John of Nepomuk. Then I hear the outer door closing and being locked, too. Oh, bloody hell, I think! So that’s the way it is. It is quiet. I sit and think: now, how to write that national anthem? I put the text in front of me. I read it and think again. And as I am thinking, I remember the words of my first teacher in Pressburg who said: ‘Son, when you compose some kind of sacred music, always think of the sound of the bells first.’ And there, in the silence of that room, the bells of Pressburg ring in my ears. A feeling of awe comes over me. I put my hand on the piano and note after note comes. Not an hour passes, and the National Anthem is ready…’*

This recollection shows how sometimes it is the little things that can make the difference in the creation of a cathartic, life-changing work. In this case, the chance meeting of a theatre director and a composer on the street, just before the deadline of a music competition. It took Erkel’s exceptional sensitivity as a composer to turn Kölcsey’s ‘Hymn’ into a real national anthem. Or perhaps it took even more than that. Because

for the ‘Hymn’ to become a true anthem of Hungary, it also needed to be perceived by Hungarians as their own.

There is something in our national anthem that makes it mean something important and inexplicable to every Hungarian. The hallmark of great pieces of art is that the reader or listener feels as if they express something very important that they cannot. As if they speak from their heart, expressing their innermost, most sincere desires and dreams. It is this mysterious quality that Hungarians feel when listening to the National Anthem: that it really comes from our hearts, it is our prayer, the prayer of every single Hungarian to the Creator.

The joint work of Kölcsey and Erkel spoke to the deep beating heart of the Hungarian people. It was an exceptional moment—a rare occasion in the life of a nation. An anecdote about Mátyás Rákosi, the head of the Communist Party and the de facto leader of Hungary from 1947 to 1956, says that he wanted a new national anthem, and he asked composer Zoltán Kodály and poet Gyula Illyés to write it. However, Kodály categorically turned down the request, asking why should we have a new anthem when we already have a perfect one? And surprisingly, for some reason, Rákosi did not push his crazy idea any further. It seems that our anthem is indeed under heavenly protection. The National Anthem also reminds us every time we sing it that we belong together in our hearts, that there is indeed something that we now call an intellectual, spiritual togetherness.

This is a unity of Hungarians that cannot be broken by any ideological or political will.

Kölcsey could not have foreseen all this on that olden January day. But what he certainly sensed was that the poem he had finished off at his desk was quite well done. Something was born on that winter day in Szatmárcseke, which proved to have a decisive effect on the spiritual life of the whole Hungarian nation.

*This passage was translated by Hungarian Conservative.

Related articles:

Click here to read the original article.