‘Intellectual’ as a term can be traced back directly to the word ‘intelligence’, which has a close etymological and direct connection with the Latin term intelligentia. The root of the word is the verb intellegō, the meaning of which is strongly related to ‘perception’ as well as to ‘feeling’ and ‘investigation’.[1]

In the Middle Ages, the Greek noun νοῦς [nous] was translated as ‘intellect’, which does not simply mean comprehension, but is a term derived from Greek philosophy (mainly understood in the Platonic and Plotinian neo-Platonic sense), essentially meaning the understanding of truth or reality. However, the term can only be understood if it is placed in the context of Platonic—and not, for example, Stoic—philosophy. Just as for Plato true reality was the ideas and not the material in which the ideas are merely reflected, so too Platonic nous had to refer above all to the conception of ideas: that is, to what is beyond mere material reality and is real/true indeed.[2]

‘Rationality’, on the other hand, is derived from the Latin word ratio, the etymology of which is more likely to be ‘count’, ‘account’, ‘number’, or ‘calculate’ and only figuratively means mental action: reasoning, judgement, or understanding.[3] While pure intellectuality is primarily synthesis and only secondarily analysis, pure rationality is pure analysis without real synthesis.

The fact that intelligence, and by implication intellectuality, today means something that is simply associated with rational ‘reason’, with calculation and the counting of things, is also a consequence of empiricism that found expression above all in the philosophy of Bacon, Hobbes, and Locke in the 16th and 17th centuries. These thinkers are ‘pre-intellectuals’ in the modern sense. They did not consider the fundamental principle of the world, the beginning in the spiritual sense, the arkhē, as primary, but the material form of the world. Bacon translated and replaced the intellect in the sense of nous with the English term ‘understanding’, literally meaning ‘to stand under something’. Well, this interpretation was indeed ‘under’ the one used by the ancient Platonists and later by the medievalists, who still assumed that reality did not correspond to the appearance of reality, ie they were not deceived by the limitations of human perception. Nor did they assume that things were always as they appeared to be.

The task of intelligence, according to the ancients and the medievalists, is precisely to

find in constant change the solid point which is the cause and origin of all change.

For if it were not, change itself would not be possible either. Metaphysics does not follow from asserting the ‘intrinsic’ non-existence of the world. It follows precisely from the fact that no one can deny the existence of the world by argument and that everyone, at least among those who seek an explanation of phenomena, must raise the question of the cause of the world.

In the case where something does not have a solid ‘self-identity’, that is, it is, like the Heraclitan stream, constantly in creation and constantly in decay, it also means that it cannot be the cause itself—for if it was only changing, there would be nothing at all. All experience of phenomena induces solid things to exist and then to disintegrate and decay. They do not evolve, as the modern evolutionist believes, but disintegrate. We may postulate evolution, but that is not what we see in the world.[4]

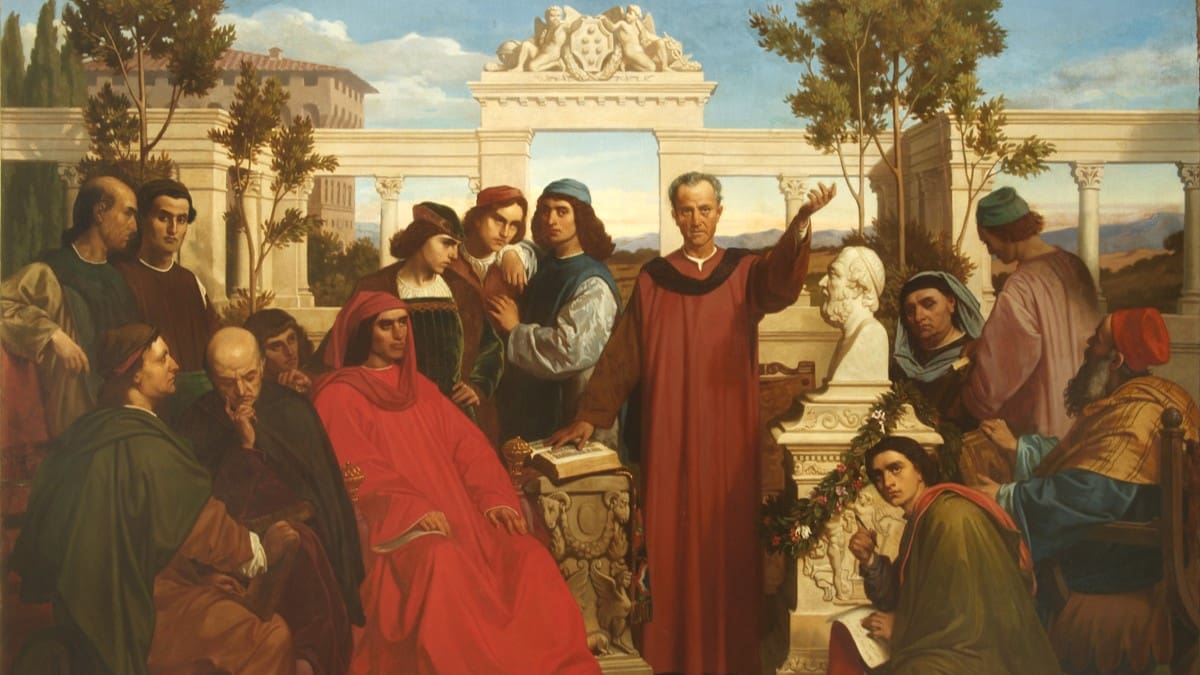

Conservatism and Intelligence

The idea that the existence of the non-variable is proved by the very existence of the variable that anyone can experience, if the existence of variable existents can be inferred from their non-variable basis, then not everything can be variable, thus can be called an ‘ontological theorem’ after Leibniz and St Anselm, but we do not necessarily have to call it that. It is simply an evident experience: it appears in the mind when the mind, in contemplating change, also perceives a direction opposite to the direction of ‘progress’ (change and deterioration). This thought, the perception of this direction, can be called the fundamental basis of actual thinking.

If everything were only change, evolution, and constant flow, change would ‘devour’ its own principle. If there were not a counterforce to the processes experienced by empiricism, there would be no change: for through the ceaseless transformation of things into each other, ‘material’ itself would not have any stability and would be incapable of creating further forms from itself. Accordingly,

if everything were variable, imperfect, and perishable, nothing would exist.

The conservative is, above all, the man who does not want to experiment endlessly, but wants to preserve something—or more precisely, to preserve and represent the non-variable in the variable, in the spirit of an ideal fidelity which is the cause, the beginning, and the origin of all change. So-called conservatism, which does not need to be defined in a ‘dogmatic’ sense, is above all an intellectual attitude. Philosophical formulations also appeared in the world only at a time when the principle of change seemed to devour all other principles. It appeared when the pace of change became so rapid that the forces of disintegration, dissolution, and the ultimate dismantling of structures, also emerged.

Simple, thoughtless ‘traditionalism’ or a so-called love of ‘habits’ is not conservatism, just as a simple love of freedom is not ‘liberalism’, nor an emphasis on the importance of community is ‘socialism’. For conservatives, an undoubted love of social customs, and especially a steadfast adherence to social institutions, have in most cases stemmed from the fact that they derived, at least before modernity, from a complex philosophical–theological background worldview, the grand synthesis of the European Middle Ages, which was above all Christian and ancient in origin, and which was smashed by the brutal hammer of modernity (the Renaissance, the Reformation, and the Enlightenment). It was also the basis of the great culture and the system of customs related to it which conservatives have tried and are still trying to preserve as far as they can, even against a tide that may, after all, prove inexorable.

If the ideological and cultural facts did not exist, the love of habits would be, indeed, simple anti-intellectualism. It would be born precisely out of non-thinking and a blunt acceptance of the flux of phenomena: an accusation with which their opponents, such as John Stuart Mill, often charged conservatives. But this is not the case. The opposite attitude to the conservative one is to be found precisely in the modern ‘consumer mentality’—that is, a kind of idleness that always accepts things as they (currently) are. If this were indeed conservatism, Mill would undoubtedly be right.

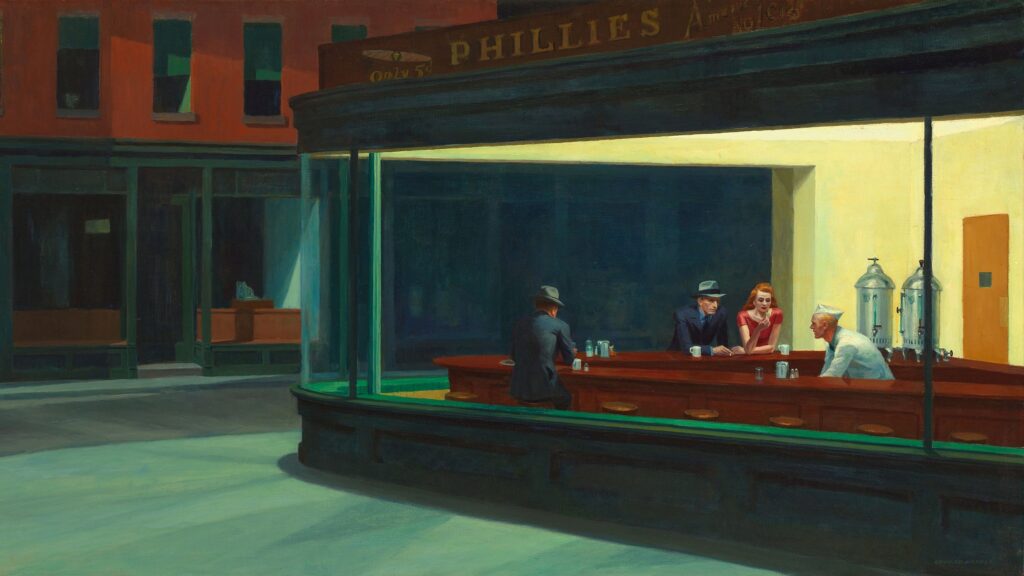

All human experience shows that

civilizations, states, and societies are always subject to change and, in this context, to decline.

However, while the progressive intellectual believes that change usually means improvement, the conservative thinker is critical of change because, in his experience, it usually means deterioration. And indeed, in a way comparable to the physical law of entropy, the world is witnessing the disintegration, dissolution, or slow erosion and corrosion of what once existed in an orderly fashion, so real ‘progress’ is in fact very rare and contingent. There are examples, but evolution is always something that occurs in a way that is contrary to the general laws of the world, similar but not quite identical to the sudden and barely explainable ‘jumps’ in natural processes that Darwinists call mutation in natural science. Conservatives are aware that it is impossible to fight the eternal rhythm of the laws of physics with human strength, and that the world is gradually deteriorating, but it still strives to oppose the centrifugal force in some way. From the periphery, the increasingly peripheral circular movement turns towards the origin, the centre, the axis, counteracting to seek the non-variable in the variable. The conservative always tries to preserve at least something of the previous, and hence more organic, states, to maintain it amidst the ever-accelerating rotation. On the other hand, the ‘progressive’ is in fact drifting with entropy.

The conservative—although it is not at all necessary, or even particularly worthwhile, to speak of ‘isms’ here—is above all a man who wishes to hold on to the ontological essence he perceives behind the ever-changing tide of phenomena. In a certain and specific sense, this can also be linked to conservatives’ attraction to the state, to the idea of the state. The Hungarian word ‘state’, which arose during the language reform and is a mirror translation of the Latin term status, evokes the image of ‘stasis’. And what is exactly opposite to it is the expression ‘stream’ (cf. Heraclitus’ ‘river’). The state always refers to something that represents the constant in the change, or at least something that holds up the flow for a while that in other respects is the ever-rotating wheel of life, that is, of creation and destruction (ananké). The state, and above all its foundation is, therefore, a kind of emergence from the flow, an ‘island’ where man can at least ‘set foot’.[5] The link between the state and holiness is therefore natural for conservatives: there is a definite analogy between the existence of the state and God. The state as an island rising out of the river, and the head of state is its representative, therefore bears the various hallmarks of sacrality in all archaic cultures and civilizations: hence the concept of the ancient ‘god-kings’, the medieval kings ‘ruling by the grace of God’, and the sacral character attributed to (state) power.

The idea of God is ‘non-variable’, which above all challenges the various relativisms. Among others, the so-called ‘conservatism’ of religions stems from this fact, and that is why

‘religious people’ are generally more conservative than their atheistic and materialistic (‘non-religious’) counterparts.

However, real conservatism has little to do with conventions, which are also ever-changing. The word ‘convention’ originally means ‘rule’, ‘agreement’, or ‘contract’. A conservative may keep them as well, but he is not a conservative just because of keeping them. He can even discard them, especially if these rules, contracts, and agreements no longer express anything, or they themselves arise from constants that are contrary to the non-variable that conservatives actually wish to preserve in the world.

As Anthony Quinton puts it, conservatism ‘in both its forms…rests on a belief in the imperfection of human nature.’[6] While this is undoubtedly a true and important definition, Quinton does not emphasize that a critical view of change is a necessary precondition for conservatism, a fact that can be traced back to the observation that the conservative ‘usually experiences the process of change as a loss.’[7] Indeed, no conservative assumes that change necessarily leads to improvement, or that ‘progress’ is both a necessary and automatic process.

There is no such thing as a consistent atheistic conservatism, at least not one that does not want to be in constant contradiction with itself. The idea of God can be accepted on the basis of Revelation or ‘natural theology’, but to adequately posit either requires an intelligence beyond rationality, nous, or intellectus: one either has it or does not. Before the corrosive spirit of purely rational analysis without synthesis became widespread, societies were conservative because they perceived the non-variable essence behind phenomena not only through their most eminent intellectuals but also collectively. The ‘men of the spirit’ in each age had a particular connection with this spiritual essence, a relationship of a different quality than most of society. This is the origin of true priesthood and also of true ‘intellectuality’. The non-variable essence, whatever the form of religious revelation, or the lack of it, was also considered by those who were unable to look from the direction of finite phenomena to the ‘infinite’ essence behind them, as ‘the ultimate cause’.

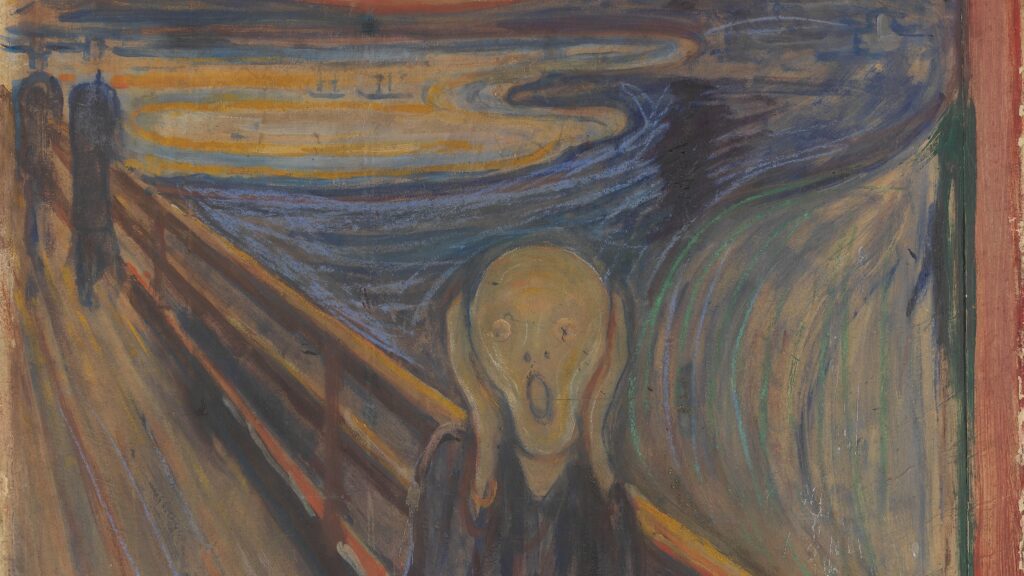

Religion, regardless of the concrete form of revelation, follows first and foremost from the metaphysical sense of individual human beings, which makes them feel and know that

the phenomena of the world (including their own bodies) are subject to change, that is, to decay and destruction.

The origin of religious thinking is not the ‘fear of death’ associated with the inevitable destruction of one’s own body, the ‘ultimate horror of destruction’, as materialistic religious studies once held. It is based on a rational interpretation of metaphysical fact, derived from intelligence, not measurable by any IQ test, that if the world, despite its ubiquitous general entropy, does exist, and exists in an ordered and structured form, there can only be a cause beyond the phenomena themselves. It then follows that the ultimate cause cannot be material in the literal sense.

[1] See for example the following analysis: Charlton T. Lewis and Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1879. https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.04.0059:entry=intellego, accessed 3 March 2023.

[2] Plato, Timaeus, pp. 27d5–8a4.

[3] See the online etymological dictionary for ratio: https://www.etymonline.com/word/ratio, accessed 7 March 2023. It is interesting to note that the Late Latin adjective moderna, modernus, modernum, according to the online etymological dictionary, goes back to the adjective modo, one of whose meanings is also related to measurement. See https://www.etymonline.com/word/modern, accessed 12 January 2024.

[4] As Robid G. Collingwood writes: ‘The idea of history as a progress from primitive times to the present day was, to those who believed in it, a simple consequence of the fact that their historical outlook was limited to the recent past.’ The Idea of History, Gondolat, Budapest, 1987, p. 396.

[5] From the mid-19th century onwards, the state, occupied by a variety of ‘progressive’ forces, has generally been less friendly to conservatives, hence, for example, the phenomenon that in certain situations it is the conservatives who have to act as ‘anti-state’ revolutionaries. While the emphasis on the authority of the state may have a conservative connotation, state totalitarianism is a phenomenon that is not conservative at all. This kind of over-extension of the state is specifically and explicitly modern, and generally also uses the state to impose some kind of developmental project on society.

[6] Anthony Quinton, A tökéletlenség politikája (The Politics of Imperfection), Pécs, 1995, p. 16.

[7] Attila Károly Molnár, Ki mit konzerválna? (Who Would Conserve What?), Századvég Kiadó, Budapest, 2022, p. 328.