Despite Hungary currently having an outstanding gold reserve due to the responsible policies of the government and the Hungarian National Bank, this has not always been the case. The reserve has faced many challenges, including the two world wars, Trianon, communism, and left-wing sell-outs.

Following the establishment of the Hungarian National Bank in 1924, a condition of the loan from the League of Nations (the precursor of the United Nations) that allowed for an independent monetary policy, the Hungarian economy managed to reach pre-war production levels by 1927, when the new currency, the pengő was introduced. However, these successes were short-lived, with the Great Depression hitting the Hungarian economy hard. The markets for Hungarian grain were lost due to the appearance of cheap American grain, and international banks withdrew their loans. Using the gold and foreign currency reserves for repayments, mitigating inflation and the fall in the purchasing power of the pengő resulted in their serious depletion.

Recovery was aided by the 1934 commercial treaties, known as the Rome Protocols, signed with Germany and Italy. However, these agreements pushed Hungary further towards the Axis powers, which Hungary paid for dearly later.

During WWII, 40 per cent of Hungary’s national wealth was destroyed,

and the country was also required to pay two and a half years’ worth of GDP in war reparations. To give an idea to the reader of the scale of destruction the country suffered: 1,850 out of our 2,100 locomotives were destroyed, and the inflation was the highest in the world at the time.

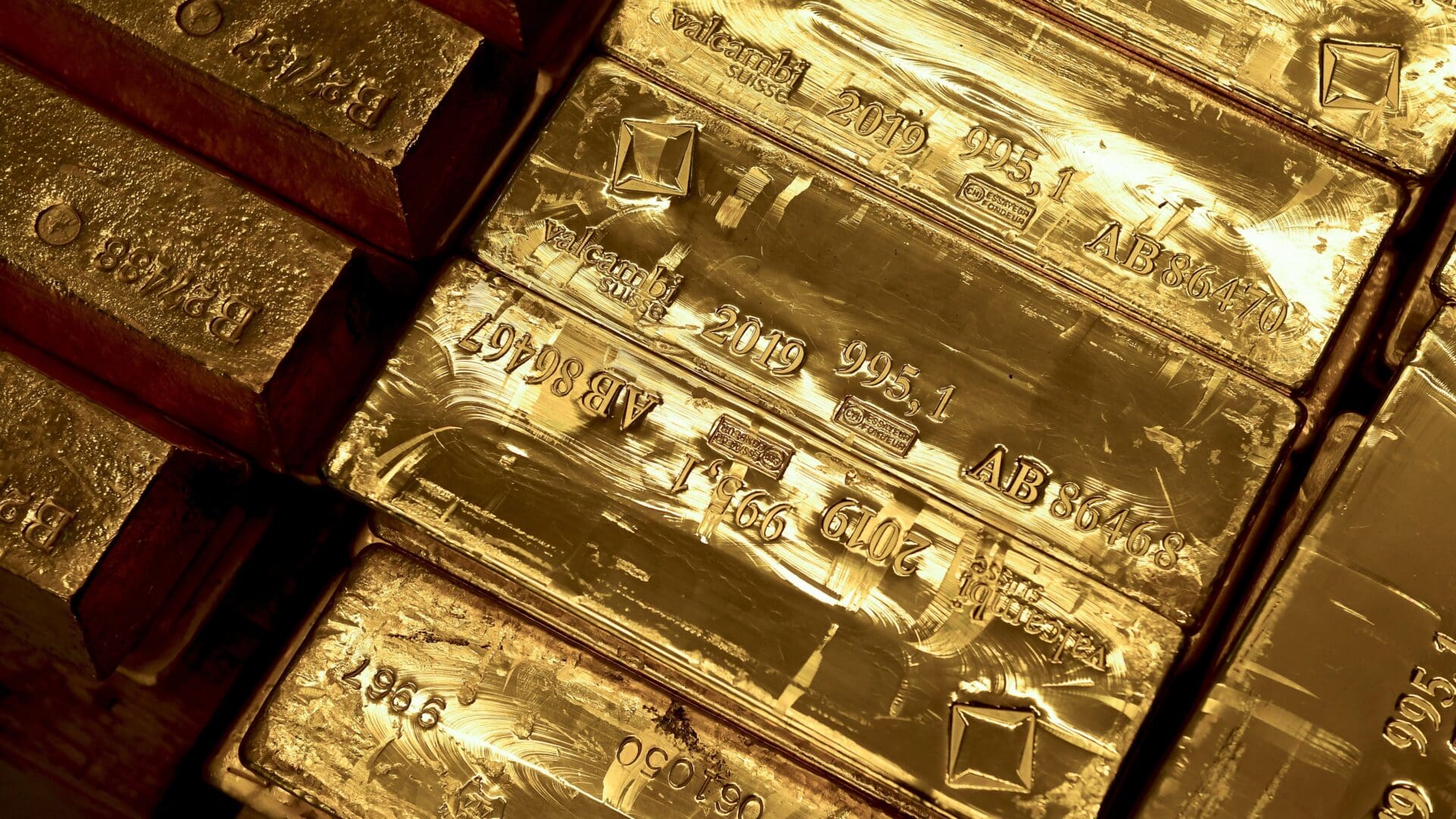

The economy of Hungary could be restarted thanks to the gold reserve rescued by the dedicated employees of the Hungarian National Bank (MNB). As the war progressed, MNB staff evacuated the bank and the Hungarian state’s assets, 600 crates and 33 tonnes of gold, banknotes and documents, to Spital am Pyhrn, a settlement in Upper Austria, in a train that later came to be known as the Gold Train. The train also carried deposited valuables and documents, including King Matthias’ Corvinas (the Corvinae) and two platinum metre bars.

Following the war, a delegation led by Prime Minister Ferenc Nagy met US officials in Washington on 18 and 25 June 1946 to discuss the restitution of the MNB’s gold reserves, art treasures, and other valuables. On 21 June, the US State Department officially announced the restitution. Part of the spoils of war were also returned to Budapest in August 1946.

The gold reserves thus

could be used as collateral for the new Hungarian forint, which was introduced on 1 August 1946.

Hungarian history took a tragic turn with the Communist takeover, the Iron Curtain, 1956, and the reprisals. The gold reserve nevertheless continually increased due to the gold-based forint and global market trends. By the 1970s Hungary’s gold reserve had grown to about 70 tonnes. During the regime change following the fall of the Iron Curtain, however, the MNB gradually sold almost all of it. By 1992 the national gold reserve had fallen to around three tonnes, and the proceeds from the sale of gold were invested in what was thought to be safe and high-yielding foreign government bonds. However, the promised returns were not realized. In 1990, during his first term as central bank president, György Surányi led the MNB in converting a significant portion of the national gold reserve into cash, amounting to 43.5 tonnes. The reserve was sold at 380 USD per ounce, mainly to buy dollars. The reason given for this move was that the return on gold was much lower than the return on the foreign currency it was exchanged for. In reality, gold, valued at approximately 1.4 million ounces at the time, was sold for around half a billion dollars. At today’s exchange rate of approximately $2,000 per ounce, it would be worth over $2.8 billion today.

In total, Hungary lost $2.3 billion as a result of the ill-advised policies of the MNB.

It was not until a right-wing government came into power that the situation changed. Since 2018, our reserve has increased thirtyfold. Hungary currently holds a gold reserve of 95 tonnes, valued at approximately 2 trillion HUF. This places Hungary as the holder of the 38th largest gold reserve in the world, putting it higher on the list than countries such as Australia, Denmark, and the Emirates. In addition, Hungary has the highest per capita gold reserve in Central and Eastern Europe. The increase in the gold reserve can be attributed to the repurchase of reserves previously sold by the left, with the right purchasing 92 tonnes to replace the 62 tonnes the left sold. In retrospect, the decision to invest in gold proved to be profitable as it was purchased before the surge in gold prices, resulting in a profit of 345 billion forints during the challenging year of 2022. The contrast between opposing views can be obviously quantified in terms of gold as well…