The following is a translation of an article written by Endre Sal, originally published on Mandiner.hu.

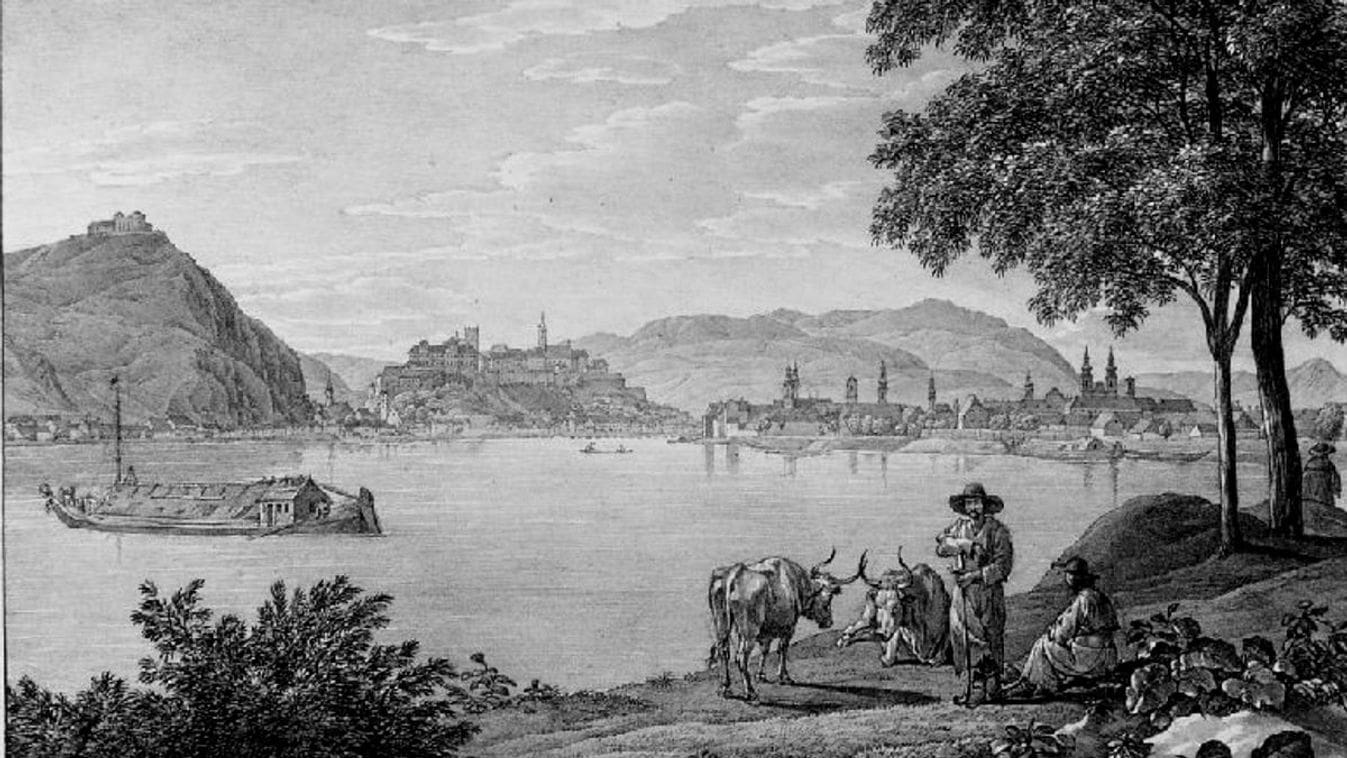

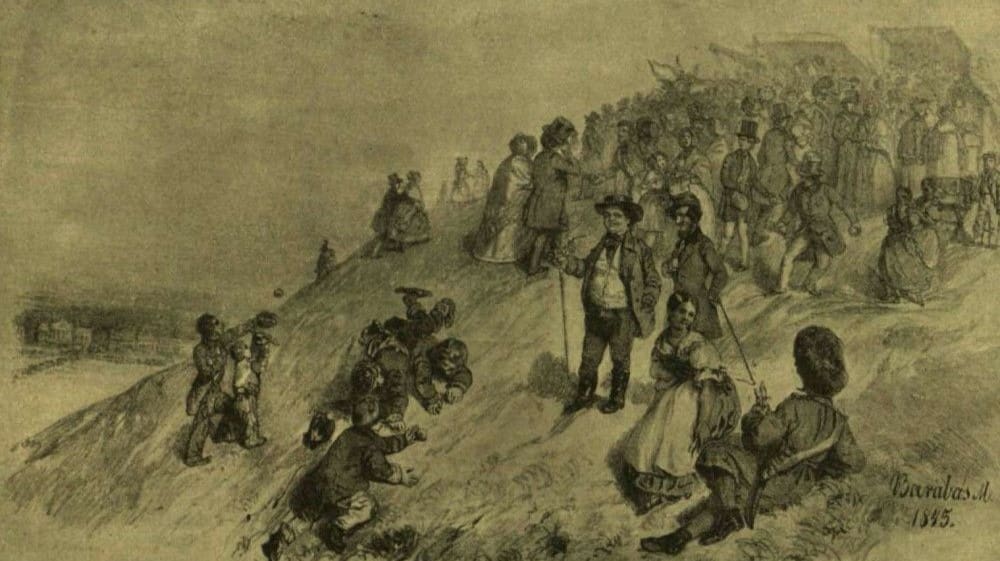

Although it is hard to imagine today, in Reform Era Hungary everyone hurried up to Gellért Hill in Buda on Easter Monday, and it was not uncommon for many to eat themselves to death after fasting during Lent.

In 1826 some 10,000 people climbed up to Gellért Hill on Easter Monday. There performers, innkeepers, and musicians awaited the celebrators, and those who wanted to try their luck could even play dice. One of the highlights of the dance and merriment was when a crowd of children waiting at the foot of the hill was thrown a bunch of apples, and they were delighted to pick up the intact ones. This was the way things happened in 1835, too, but then the rain put an end to the fun. That year even the traditional Easter procession was cancelled because people were almost submerged in the mud in Pest, and the hills of Buda were covered with snow.

As today’s Chain Bridge was inaugurated only in 1849, Pest and Buda were connected by a temporary bridge until then. In 1837, this temporary bridge was hit by a ship ‘laden with iron’, which severely damaged it, so on Easter Monday those heading to Gellért Hill could not cross the river. Then, in 1847, it was the weather that intervened; as one of the newspapers of the time put it:

‘The merrymaking on Gellért Hill attracted a huge crowd on Monday. Although the strong wind almost swept them all into the Danube, they still had fun.’

The paper also discussed what people in Pest had done during the Easter holidays:

‘Others took the steam train all the way to Vác, but Vác is the embodiment of boredom. The green is not green yet, no one has moved there. So: the capital’s appetite for amusement was left without an outlet on Easter Monday.’

The churches of Pest were full on Holy Saturday and Easter Sunday, and then on Monday people indulged in Pest-style water sprinkling. In 1835 a paper wrote: ‘The people of Pest baptize each other well, with scented water. If nature has deprived someone of fragrance, then at least she should smell good on Easter Monday.’

In the countryside there was sprinkling, too, but very differently. The custom was that maidens would be grabbed by boys, dragged to the nearest river and ‘dipped’ in it. If there was no river nearby, they would be taken to wells, laid in troughs and doused with cold water. On more than one occasion

the poor girls would get a stroke from the cold water or die of pneumonia a few days later.

That is why the 1835 newspaper noted that ‘in some places, this kind of bestial water sprinkling is banned’.

In those days, it was Easter rather than Christmas that was accompanied by a great deal of eating and drinking, and the sudden feasting after the Lenten period took many lives. In 1834 newspapers wrote: ‘During the Christmas holidays, it is rare for anyone to die of overeating, whereas it often happens during Easter.’

Related articles:

Click here to read the original article.