This article was published in Vol. 4 No. 1 of our print edition.

Weeks of farmers’ protests across Europe seem to have broken Brussels, with the European Commission making significant concessions to disgruntled farmers. However, quick symptomatic treatments will not resolve the deep-rooted problems of European agriculture. One of the primary causes is the reluctance of the European left-wing elite to adequately represent farmers’ interests. This attitude may come at a high cost for them in the upcoming European Parliament elections in June.

Tractor-blocked motorways, barricaded border crossings, and fertilizer-sprayed office buildings mark the beginning of the new year as farmers’ protests spread across Europe. Demonstrators, dissatisfied with both EU and national policies, have taken to the streets from Germany to France, Italy, Romania, Greece, Belgium, Spain, Poland, and Portugal. These protests have led to transport paralysis and a significant decline in trade, impacting economic flows throughout Europe. It would be easy to assume, on the basis of news reports, that discontent was triggered by a single measure, but looking at the bigger picture it becomes clear that years of restrictions and a disregard for farmers’ complaints have led to the current chaotic situation. While the reasons vary from country to country, there are issues common to all the protests. These include the new EU Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), the unrestricted influx of Ukrainian grain into the EU, and the green regulations imposed by the European Green Deal, all of which have had a negative impact on agriculture.

In the EU, farmers receive subsidies through the programme known as the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). Agriculture is distinct from other businesses for several reasons. The unpredictability of food production, influenced by factors such as weather, climate, and disease, sets it apart. Additionally, there is often a time lag between the demand for products and the speed at which they can be produced. Moreover, farmers’ incomes are, on average, approximately 40 per cent lower than those in other industries.1

‘The common agricultural policy is key to securing the future of agriculture and forestry, as well as achieving the objectives of the European Green Deal’,2 as is stated on the European Commission’s website presenting CAP 2023–2027. The new CAP aims to ensure a sustainable future for European farmers, with a focus on better-targeted support for smaller farms and increased flexibility for EU countries to adapt measures to local conditions. The Commission’s website specifically underscores the new CAP’s alignment with the objectives of the European Green Deal. To this end, much stricter conditions have been set for the payment of subsidies. For example, on every farm at least 4 per cent of arable land is dedicated to biodiversity and non-productive elements, with a possibility to receive support via eco-schemes to achieve 7 per cent. As part of the new changes, EU member states will now have to make sure that at least 35 per cent of their rural development budget and 25 per cent of direct payments to farmers are dedicated to environmental and climate measures.

As Mandiner highlighted in its analysis, many of the measures introduced in the new CAP ‘result from the social transformation aspirations of left-wing movements, which, among other objectives, seek to diminish the autonomy of the middle class and farming communities and radically transform people’s lifestyles. This includes the introduction of alternative protein sources, such as artificial meat and insects, in conjunction with a reduction in meat consumption.’3 It is no coincidence that a set of measures, predominantly advocated by Green and Socialist MPs, politicians, and parties, has shifted the responsibility for climate change from heavy industry, chemicals, and mining to agriculture, particularly livestock production. The measures within the new CAP, including progressively stringent animal welfare standards, discreetly increased bureaucratic burdens, higher carbon and other taxes, elevated fuel costs, stricter rules on plant protection, a reduction in cultivated areas, and the compelled dismantling of family farms, are, in practice, designed to render agricultural production unfeasible.

‘A shift to the right might set Europe on the path to regaining strategic autonomy, particularly beneficial for European farmers’

Farmers perceive the effects of these recent changes and EU green targets as unfair and challenging to manage, expressing concerns that these measures could jeopardize farming livelihoods. Luc Vernet of the Brussels-based think tank Farm Europe told the BBC: ‘Farmers are being required to do much more…with less support. They don’t see how they can cope any longer.’4

Free trade agreements established by the EU with third parties have further heightened farmers’ discontent, especially regarding the proposed agreement with Mercosur, the trade bloc comprising Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay. The European Commission and Mercosur members would like to ‘sign the agreement at the next World Trade Organisation ministerial summit, from 26 to 29 February, it is said in the halls of the Commission’ after the failure last July, Maxime Combes, economist and a leader of the opposition to the agreement, told Euractiv.5

The EU–Mercosur Trade Agreement has long been a target of criticism from farming organizations in the EU. They argue that the agreement would put European farmers at a significant disadvantage by generating substantial annual import volumes into the EU, including 99,000 tonnes of beef, 25,000 tonnes of pork, and 180,000 tonnes of poultry and sugar.6 Concerns about the agreement have also been raised by Copa Cogeca, a group representing EU farmers’ organizations and agricultural cooperatives. In a letter addressed to Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, the organization labelled the agreement unacceptable. As the letter stated: ‘Continuing to push through a deal will be seen as a further provocation by farmers and will increase the rejection of the decisions taken by the European Commission.’7

The war in Ukraine has impacted nearly every aspect of people’s lives in Europe, and agriculture is no exception. In fact, farmers are arguably among the primary victims of the conflict that has been unfolding in the EU’s neighbourhood for the past two years. Since February 2022, farmers’ costs—especially energy, fertilizer, and transport expenses—have increased significantly. Member state governments and retailers have taken measures to mitigate the surge in food prices resulting from the rising costs of agricultural production, in response to the impact of the crisis on consumers. According to Eurostat data, farm-gate prices, which represent the basic price farmers receive for their produce, dropped by almost 9 per cent on average between the third quarter of 2022 and the same period last year. Only a few products have deviated from this trend.8

As if that were not enough, Ukrainian grain has inundated European markets, placing EU farmers at a further disadvantage. Ukraine, one of the world’s largest grain exporters, accounted for approximately 10 per cent of global wheat exports and nearly 50 per cent of sunflower oil exports before the outbreak of the war.9 However, when the conflict erupted, shipments by sea came to a halt, posing a significant risk to global food security. Subsequently, in July 2022, Kyiv and Moscow brokered a deal with the UN and Türkiye, known as the Black Sea Grain Initiative, allowing grain exports to resume from three Ukrainian ports. Nevertheless, the agreement expired in July 2023, and the terms have not been renegotiated since.

As the sea route remains unsafe, Ukrainian grain is being transported to various European ports via Eastern and Central European states. However, in practice, this has led to products grown under more lenient regulations flooding European markets. To safeguard their farmers, five member states—Hungary, Slovakia, Poland, Bulgaria, and Romania—appealed to the Commission. Succumbing to the pressure, Brussels agreed to permit these member states to impose certain restrictions on imports of Ukrainian cereal products. This measure was later lifted in September 2023, following a decision by the Commission.10

Ukraine poses and will likely continue to pose a significant challenge for European farmers. The potential accession of the war-torn country to the EU raises concerns about the loss of substantial subsidies for the agricultural sector. The majority of agricultural subsidies are allocated per hectare, and the sheer size of Ukraine would potentially jeopardize family farms across Europe. The situation is equally discouraging for cohesion funding.11 The amount of cohesion funding per region is determined by the ratio of GDP per capita to the EU average. Regions eligible for support are those with a ratio below 75 per cent. Given Ukraine’s size and underdevelopment, it would likely fall well below the average, resulting in no regions outside Ukraine benefiting from cohesion funding under the current circumstances.

The governments of the countries affected by the protests, upon recognizing the scale of the demonstrations and the potential negative consequences of their prolongation, immediately agreed to offer concessions to the farmers. The German government was the first to take action, responding to protests triggered by a reduction in fuel subsidies, which was deemed necessary due to a significant budget deficit. Although the Scholz cabinet had initially announced on 4 January that it would withdraw a portion of its subsidy-cutting plans, this move failed to appease the farmers. The protests, spearheaded by the German Farmers’ Association (DBV), are calling for a complete abandonment of the proposed savings plans.12

The protests were brought uncomfortably close to the Brussels elite, with demonstrations taking place during the EU summit on 1 February, including in front of the European Parliament in the Belgian capital. The mounting pressure forced the Commission to backtrack and announce a relaxation of some measures introduced by the CAP. These plans include a proposal to shield farmers from the price effects of Ukrainian imports while also allowing them to utilize portions of the 4 per cent of land that was initially slated to be left barren. The European Commission stated that this proposal ‘provides a first concrete policy response to address farmers’ income concerns.13 The European Commission also proposed a cap on some Ukrainian agricultural products as a concession to farmers.14 This includes limits on Ukrainian sugar, poultry, and eggs. This allows the EU to maintain ‘economic support for [Ukraine], while taking EU farmers’ interests and sensitivities fully into account’, Trade Commissioner Valdis Dombrovskis said in a statement.15

‘The measures within the new CAP [Common Agricultural Policy] are, in practice, designed to render agricultural production unfeasible’

The Commission is also withdrawing the Sustainable Use of Pesticides Regulation (SUR), which aimed to halve the use of pesticides by 2030.16 The regulation also included a provision for a complete ban on these products in sensitive areas such as urban green spaces and Natura 2000 sites. ‘The Commission proposed SUR, with the worthy aim to reduce the risks of chemical plant protection products,’ von der Leyen told MEPs at the European Parliament in Strasbourg on 6 February. ‘But the SUR proposal has become a symbol of polarization.’17 This marks a significant success for farmers and a symbolic defeat for the left and the Commission.

Moreover, the Commission dropped references to agriculture in the common 2040 climate target. Also excised were recommendations for citizens to make changes to their behaviour, like eating less meat, and a push to end fossil fuel subsidies.18 However, according to Politico’s 6 February newsletter, there is a twist: the Commission is also preparing a technical analysis of the plan, which makes it clear that even though the policy text has removed provisions for farmers, agriculture will still have to reduce its own emissions to meet the overall 90 per cent target.

To address the concerns of French farmers, Prime Minister Gabriel Attal has emphatically reassured the public that France opposes the proposed agreement with Mercosur. In February of last year, French President Emmanuel Macron stated that he would reject the agreement if it did not include so-called mirror clauses. These clauses demand that farmers in Mercosur countries be subject to similar restrictions as those that apply to EU producers.19

However, quick fire-fighting measures do not address the underlying problem: the left-wing political elite in Western Europe is largely disconnected from ordinary people and either fails to understand or refuses to acknowledge their problems. Instead of tackling real issues, they often focus on pseudo-problems that are of interest to only a narrow group of people. A notable example is the case of ‘rule of law concerns’, which they use to target countries that deviate from the liberal mainstream, as seen in the case of Hungary.

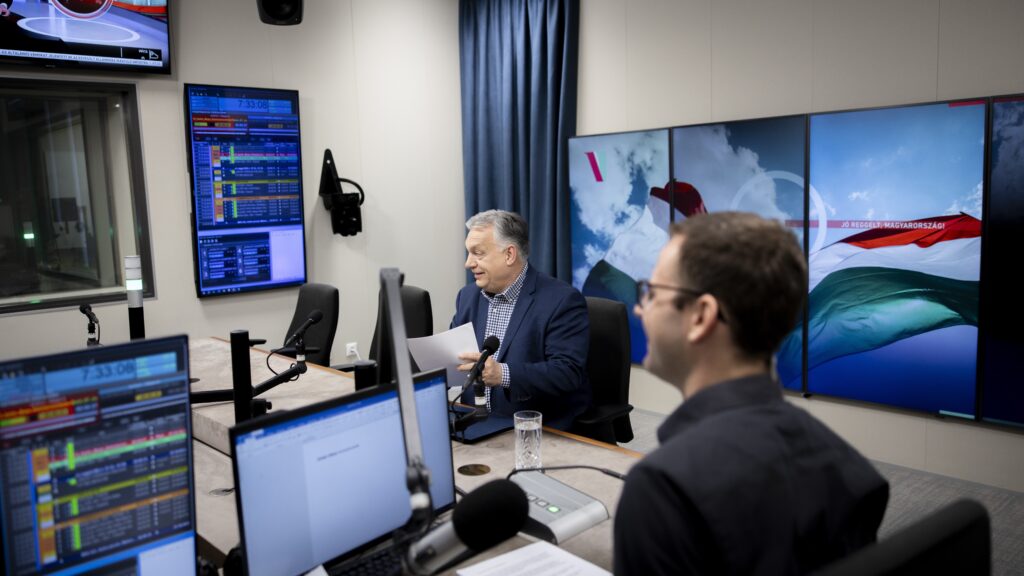

No wonder farmers, who are well aware of the political games of the left, do not take kindly to politicians attempting to ‘make peace’ with them. On 4 January, angry farmers ‘trapped’ German Vice Chancellor Robert Habeck, who was returning home from his holiday when the crowd blockaded the harbour where his ferry was due to dock. Authorities described the situation as ‘extremely tense’. In contrast, Viktor Orbán, who visited protesting farmers in Brussels ahead of the EU summit on 1 February, was warmly welcomed.20 In Germany, the right-wing Alternative for Germany (AfD) party immediately expressed support for the farmers, as did Marine Le Pen’s National Rally (NR) Party in France.

The ongoing farmers’ protests could also have a significant impact on the European Parliament elections in June. The general dissatisfaction is also reflected in opinion polls: the latest survey of the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) indicates that the political right is expected to make gains in the June elections. As the survey report put it, ‘anti-European populists’ currently top the polls in nine member states: Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, France, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, and Slovakia; and they come second or third in a further nine countries, including Bulgaria, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Portugal, Romania, Spain, and Sweden.21 The right-wing political groups in the European Parliament—the European People’s Party (EPP), the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR), and Identity and Democracy (ID)—could form a majority coalition for the first time if current trends continue until June, according to a poll by Brussels-based Politico.

Although divisions within the political groups on the right make it unlikely that a grand coalition will emerge, the reduction of the left’s dominance could itself bring about much-needed changes in European politics. These changes would not only impact agriculture but could also prioritize pragmatic, non-ideological cooperation, focusing on the real interests of the member states rather than globalist and overseas interests. As Orbán pointed out to the farmers in Brussels,22 the solution to the problem lies in replacing the current European political elite, as the current leaders will never make decisions that are favourable to farmers. A shift to the right might set Europe on the path to regaining strategic autonomy, particularly beneficial for European farmers.

NOTES

1 Rosie Frost, ‘CAP: What Is the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy and Why Is It Trending?’, Euronews (26 November 2021), www.euronews. com/green/2021/11/26/cap-what-is-the-eu-s-common-agricultural-policy-and-why-is-it-trending, accessed 6 February 2024.

2 European Commission, ‘The Common Agricultural Policy 2023–27’, https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/common-agricultural-policy/cap-overview/cap-2023-27_en.

3 Zoltán Pataki, ‘Dühös gazdák kora’ (The Age of Angry Farmers), Mandiner (2 February 2024), https://mandiner.hu/kulfold/2024/01/duhos-gazdak-kora, accessed 6 February 2024.

4 Laura Gozzi, ‘Why Europe’s Farmers Are Taking Their Anger to the Streets’, BBC News (27 January 2024), www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-68095097, accessed 6 February 2024.

5 Paul Messad, ‘France Reaffirms Opposition to EU– Mercosur Deal as Farmers’ Protests Mount’, Euractiv (29 January 2024), www.euractiv.com/section/agriculture-food/news/france-reaffirms-opposition-to-eu-mercosur-deal-as-farmers-protests-mount/, accessed 6 February 2024.

6 Charles O’Donnell, ‘Mercosur Talks Proceeding despite EU-Wide Farm Protests’, Agriland (31 January 2024), www.agriland.ie/farming-news/mercosur-talks-proceeding-despite-eu-wide-farm-protests/, accessed 6 February 2024.

7 ‘Copa Cogeca Requests to Meet von der Leyen over EU Protests’, Agriland (31 January 2024), www.agriland.ie/farming-news/copa-cogeca-commission-must-respond-to-eu-protests/, accessed 6 February 2024.

8 ‘Agricultural Prices Fell in the Third Quarter of 2023’, Eurostat (20 December 2023), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20231220-2, accessed 6 February 2024.

9 Jen Kirby, ‘Why Grain Can’t Get out of Ukraine’, Vox (20 June 2022), www.vox.com/23171151/ukraine-grain-wheat-russia-black-sea-odesa-food-crisis, accessed 6 February 2024.

10 Jorge Liboreiro, ‘EU Lifts Bans on Ukrainian Grain but Poland and Hungary Move to Impose Unilateral Restrictions’, Euronews (15 September 2023), www.euronews.com/my-europe/2023/09/15/brussels-lifts-bans-on-ukrainian-grain-as-kyiv-agrees-to-impose-effective-measures-to-avoi, accessed 6 February 2024.

11 Barbara Moens, ‘Inside Ukraine’s First Day as an EU Member’, Politico (22 June 2023), www.politico.eu/article/ukraine-european-union-membership/, accessed 6 February 2024.

12 Joakim Scheffer, ‘Left-Wing Leaderships Plunge Europe into Chaos’, Hungarian Conservative (13 January 2024), www.hungarianconservative.com/articles/politics/left_wing_leaderships_europe_chaos/, accessed 6 February 2024.

13 European Commission, ‘Commission Proposes to Allow EU Farmers to Derogate for One Year from Certain Agricultural Rules’, European Commission Press Release (31 January 2024), https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_24_582, accessed 6 February 2024.

14 Bartosz Brzeziński, ‘Brussels Backs Ukraine’s Duty-Free Access to EU until June 2025’, Politico (31 January 2024), www.politico.eu/article/european- union-ukraine-duties-trade-agriculture-farmer-protests/, accessed 6 February 2024.

15 European Commission, ‘EU Reaffirms Trade Support for Ukraine and Moldova’, European Commission Press Release (31 January 2024), https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_24_562, accessed 6 February 2024.

16 Eddy Wax and Bartosz Brzeziński, ‘Ursula von der Leyen Scraps Pesticide Reduction Bill, in Gift to Farmers’, Politico (6 February 2024), www.politico.eu/article/ursula-von-der-leyen-pesticide-reduction-bill-farmers/, accessed 6 February 2024.

17 Wax and Brzeziński, ‘Ursula von der Leyen Scraps Pesticide Reduction Bill, in Gift to Farmers’.

18 Karl Mathiesen and Eddy Way, ‘EU Eases Farming Demands in 2040 Climate Proposal’, Politico (6 February 2024), www.politico.eu/article/eu-eases-farming-demands-in-2040-climate-proposal/, accessed 6 February 2024.

19 O’Donnell, ‘Mercosur Talks Proceeding despite EU-Wide Farm Protests’.

20 Joakim Scheffer, ‘A Politician among the Farmers: An Image the Left Is Terrified of’, Hungarian Conservative (1 February 2024), www.hungarianconservative.com/articles/politics/farmer-protests_brussels_orban_left_disregard_rural-development/, accessed 6 February 2024.

21 Loretta Tóth, ‘Farmer Protests Give Form to General Discontent in Europe’, Hungarian Conservative (28 January 2024), www.hungarianconservative.com/articles/politics/farmer-protests_political-crisis_general-discontent_surge-of-the-right/, accessed 6 February 2024.

22 Scheffer, ‘A Politician among the Farmers: An Image the Left Is Terrified of’.

Related articles: