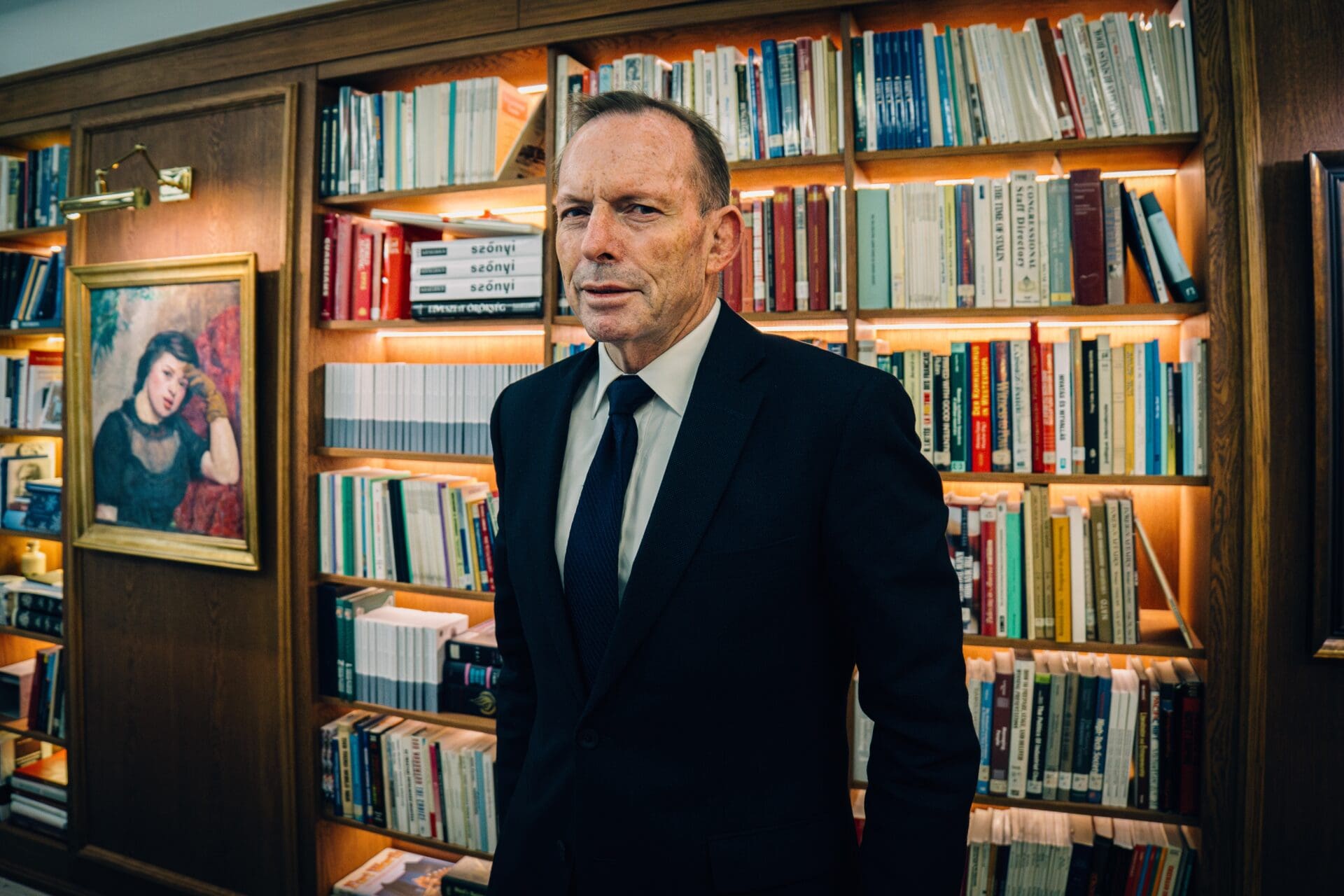

‘Hungary has become a focal point for conservative-minded people around the world, and the Danube Institute, in particular, has become a meeting point for English-speaking intellectuals who, under different circumstances, might not have paid as much attention to Hungary as we do now’, the Honourable Tony Abbott AC told Hungarian Conservative. The former prime minister of Australia, who is currently a Visiting Fellow of the Danube Institute, also emphasized that Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán was able to articulate a brand of conservatism that is both economically sensible and culturally conservative and traditionalist.

***

We can tell that you are a frequent visitor to Hungary. You have come to Budapest numerous times in recent years, including during the third Demographic Summit, and you are currently a Visiting Fellow at the Danube Institute. How do you perceive Hungary and Hungarians on the global stage?

First of all, it’s an honour to be a visiting fellow at the Danube Institute. And it’s been a pleasure to visit Hungary several times over the last few years. There is no doubt that under the prime ministership of Viktor Orbán, Hungary has become a point of light to Conservatives around the world. Orbán has sometimes been described as Trump without the downside. That’s a simplistic observation and possibly unfair to both Trump and Orbán. But, certainly, Viktor Orbán has a very long record in public life, from his early days as a strong anti-communist freedom fighter, through to his first stint in government, and now to this long and successful tenure as a prime minister. He’s been able to articulate a brand of conservatism that is both economically sensible and culturally conservative, and traditionalist. This is a bit different from the conservatism that until recently prevailed in the economically liberal and, in some respects, socially progressive English-speaking world.

For those who are traditionalists—and I believe that a significant percentage of society is traditionalists—the Orbán era has been attractive and instructive.

In recent years, Hungary has become a focal point for conservative-minded people around the world, including in the English-speaking world. The Danube Institute, in particular, has become a meeting point for English-speaking intellectuals who, under different circumstances, might not have paid as much attention to Hungary as we do now.

What do you think about the international perception of Viktor Orbán and Hungary? The Hungarian Prime Minister receives a lot of criticism, especially in the European Union, and he has been labelled as a ‘dictator’ in the liberal media.

This idea that Orbán is some kind of dictator is nonsense. A very robust leader, no doubt about that. At times he’s been prepared to go against the general EU consensus, especially in 2015, during the mass migration of people from the Middle East and Africa to Europe, which I characterized as a form of peaceful invasion. Orbán was very strong, and he built that fence to keep them out, and where that couldn’t be managed, he moved them on through Hungary to other places. This, for argument’s sake, was quite different from the approach of the Germans and, to a lesser extent, from the rest of the EU. He stood out from the crowd. This idea that he’s some kind of dictator? That’s quite wrong.

Hungary has a vigorous free press. It has a robustly independent judiciary, and it has free and fair democratic elections.

And if you’ve got an independent judiciary, free media, and fair and regular elections, you are a democracy. People can argue with the result of democracy. But they can’t say there is no democracy here.

This time, you came to Budapest for CPAC Hungary 2024. You visit many conservative conferences like this around the world. What is your impression of the conservatives’ international situation?

It’s good in some places, not in others—a mixed bag, and this is normal. The last time we’d say conservatism was globally dominant was probably back in the era of Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher and Pope John Paul II. That was a remarkable time in the history of the world. And it was certainly a great time to be Conservative. Since then, there have been ups and downs. But there haven’t been any conservative governments, at least in the English-speaking world, which have been as unambiguously successful as those of Reagan and Thatcher. I also should mention John Howard; he led a very successful center-right government in Australia, just like Stephen Harper in Canada.

There are several significant upcoming elections in the Anglosphere. The American presidential election holds the most international importance, but there will also be general elections in the United Kingdom soon, and new parliaments will be elected in Canada and Australia next year. The question is, do the Conservatives have a chance to win?

There will likely be a Republican government in the United States by the end of the year. And, unfortunately, you will probably have a Labour government in the United Kingdom. You will probably get a Conservative government in Canada sometime next year, and I think there is some prospect of a change of government in Australia, too. The current government has disappointed many people and Peter Dutton, the new leader of the conservative side of politics in Australia, is, is surprising people on the upside. So I think there is some chance that the current government in Australia will be a one-term government. But the challenge for us conservatives is always to be the best we can be. This means trying to ensure that our economies are strong and our countries are safe.

Australia and Hungary are in two different parts of the world, so their challenges are also different. However, there is one issue in which their positions are quite similar, and that is the treatment of illegal migration. Migration pressure is still very high in Europe; how would you rate the migration policy of the European Union?

The EU has had enormous difficulties in coping with the massive movements of people from poor countries to rich countries. I think the EU has largely succumbed to liberal guilt over the fact that some countries are much richer than others. Instead of drawing the correct conclusions that the countries of Europe are richer than others, which the countries of Europe should be very proud of individually and collectively because, over time, they have pursued more sensible policies, the rule of law, democracy, market economics, respect for individual rights. And they should really try to protect it instead of letting it be diluted by uncontrolled migration from the third world, which happened in 2015 and is still happening to a lesser extent. Because it is really a form of peaceful invasion. And no serious country can tolerate this, you absolutely have to have control of your borders.

And if the EU is not ready to control the wider EU border, then some countries within the EU should, as Hungary did, prepare to take over their borders and ensure that only those who are entitled to enter.

Because immigration policy must ultimately be operated primarily in the interests of those already living in the country. We know that it is good for migrants to come to countries like Australia and Hungary, as the case may be. But the governments of our countries absolutely have a duty to operate the immigration program for the benefit of their country, not for the sake of the schools of immigrants, which is taken for granted, but for the benefit of the country. In Australia’s case, we’ve always had an official formal refugee program. We’ve had it for forty or fifty years now.

How do you see the global competition between the United States and China? What implications might this competition have for the rest of the world?

I think we are in the throes of a new Cold War. And in some respects, this new Cold War could be even more difficult and dangerous than the last one. Because China is a very formidable competitor. The old Soviet Union, Russia was never more than a third-rate economy, even though it had a first-rate military back in the day. China is a first-rate economy, in part because Western Goodwill has allowed China into the global economy. And the Chinese, I guess, to their credit, have made the most of that. So China is a first rate economy rapidly developing a military to match. There’s also the issue of the Chinese diaspora, which, again, makes this Cold War slightly more complicated than the old one. However, I hasten to add that I think that Australians of Chinese background are very good citizens of our country, and they are absolutely on Australia’s side. Nevertheless, I guess it does make things slightly more complicated. It is critical that the democracies win this, just like the previous one. There is strength in that unity. But as well as being rhetorically strong, we’ve also got to be militarily strong. There is a need for a rapid rebuilding of the democracy’s military strength. Australia’s military spending is projected to move from 2% to two and a half percent of GDP. Obviously, given what’s happening in Ukraine, some countries in Eastern Europe, particularly Poland, have dramatically increased their military expenditure over the last couple of years. And what we’re doing now is the least we need to do. As we’ve seen in history, time and time again, weaknesses are provocative. And given that we do have these dictatorships on the large, whether they’re communist dictatorships in the case of China, militarist dictatorships in the case of Russia, or Islamist dictatorships, in the case of Tehran and Iran, the dictatorships need to understand that democracies are not pushovers, but if they push forward, we push back. And in the end, we’ll stand together with our fellow democracies in the cause of freedom.