‘Freedom is today’s great theme’—writes Ernst Jünger in his famous essay The Forest Passage (Der Waldgang)—‘it is this force that will conquer fear. Freedom is the main subject of study for the free human being, and this includes the ways in which it can be effectively represented and manifested in resistance.’[1]

But why does he talk about resistance, and what causes resistance at all? Don’t we live in the ‘free world’? The great movements of modernity set out in the name of freedom and liberation. First, the liberation (revolution) of science from the ‘tyranny’ of the dogma of the medieval Church (Kepler, Galilei, Giordano Bruno); then, there was the Renaissance as the ‘revolutionary renewal’ of antique wisdom; then Protestantism, which proclaimed the revolution of the Church, the free interpretation of the Bible, and the liberation of religious life. In the various political revolutions of modernity, including the triple motto of the ‘Great’ French Revolution of 1789, freedom (liberty) comes first. As a result of the liberal currents following the French Revolution, the emancipation of serfs took place everywhere in Europe, and the freedom of ‘labour and capital’ was established. In early capitalism, land could be ‘freely bought and sold’; Marxism speaks of liberation through the revolutionary process; in modern democracy there are ‘free elections’; and one of the central theme of liberalism is precisely ‘free competition’. The possibility of choice is usually connected with the possibility of freedom (liberal democracy), as if, through the various revolutionary currents, humanity had been freed from the former slavery, barbarism (or, in the terms of Aufklärist authors: from ‘superstitions’) through a series of historical developments, in the direction of a truly human life or Nietzsche’s ‘more human than human’ man.

However, during the 19th and especially during the 20th and 21st centuries, authors criticizing modernity do not necessarily speak from the perspective of order or ‘tradition and authority’, like the great reactionaries of the past, such as Metternich or De Bonald. Just as various forms of liberalism gradually have become the accepted and supported by political elites, and ultimately, the only accepted ideology in the Western world, certain strains of conservatism take over the active defence and affirmation of the philosophical idea of freedom.

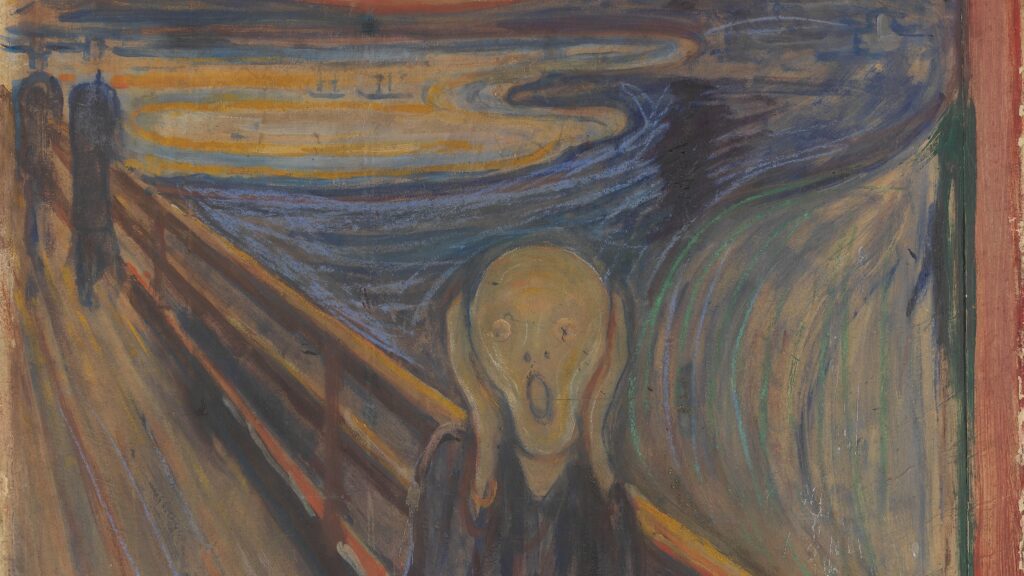

In a world created by various industrial, sexual, technical, cultural or, more recently, digital revolutions, all the factors should be present for a greater degree of freedom than ever before. Yet, in the eyes of these critics,

it is precisely freedom that suffers from one of the most essential deficiencies.

How is it possible? Whose perspective is distorted?

As Jünger follows in his essay, The Forest Passage:

‘The hopeless encirclement of man has been long in the preparation, through theories that strive for a logical and seamless explanation of the world and go hand in hand with technical development. At first there is the rational encirclement of the opponent, then the societal one; finally, at the appointed hour, he is exterminated.’[2]

Conservative (and sometimes called liberal) British Catholic authors such as Hilaire Belloc and G. K. Chesterton directly spoke of a ‘slave state’ (Hilaire Belloc: The Servile State, 1912) in connection with the modern industrial state. Belloc, still in a fashion of a classical liberal, wrote the following in 1897 regarding the current system of England:

‘The conditions which industrial development have brought about in England are the very antithesis of those which Liberalism devises in the State: capital held in large masses and in a few hands; men working in large gangs under conditions where discipline, pushed to the point of servitude, is almost as necessary as in an armed force; voters whose most immediate interests are economic rather than political; citizens who own, for the greater part, not even their roofs.’[3]

László Ottlik (writing in the 1920s and 1930s), a Hungarian political thinker deeply influenced by contemporary German and Anglo–Saxon political philosophy, treated as simple ‘fiction’ these postulates and worldview, often raised to a sacred rank by the progressivist, liberal-minded historiography (and implicitly considered unquestionable), which, according to him, actually established the ‘worldview dominance of liberal bourgeois individualism’:

‘The bourgeoisie starts from the fiction that humanity is ‘‘basically’’ made up of equal individuals, independent and rationally self-managing subjects— ‘‘homo oeconomicus’’—who, in this way, naturally all have the characteristic of the bourgeois type of person. The imagined harmonious relationship that liberal ideology calls ‘‘civil society’’ arises from the free activity of these subjects, performing economic activity…It prefers the ‘homo oeconomicus’ type over types oriented towards other value systems, ie equipped for a different way of thinking.’[4]

In his interpretation, ‘absolute liberalism’ is ‘the reduction of politics to the minimum that protects the free activity and security of the homo oeconomicus’, while the reality is that the unlimited free competition ‘mercilessly tramples those who were not born to make their living in business and do not give themselves to their vocation with heart and soul.’[5]

Ottlik saw with harsh irony the aspirations of bourgeois interests seeking to dominate the state. The political activity of ‘homo oeconomicus’ is not fundamentally characterized and guided by the Nietzschean or Machiavellian will to power, nor by mere cynicism, but rather by a specific optical illusion:

‘He does not and cannot see a conflict between his perception and reality, because in the meantime the civil legal system has transformed society in such a way that those who are not bourgeoisie no longer have the right to exist. If it is true that society consists of economically active individuals, then it is clear that anyone who is not an economically active individual has no place in society: consequently, its existence can only be an abuse that must be stopped…’

The average person trying to fit into the civilization of modern economics cannot be called free in the least, his paradigm is the product of the standard, egalitarian-materialistic cultural ideal: ‘…his spiritual endeavours are modest and his material needs are standardized, his newspaper is not interested in sophisticated editorials, but in criminal, sexual, and sports sensations, practically, this freedom is less different from the ‘‘servitude’’ in which the subjects of the ‘‘dictators’’ live.’[6]

If we look around the world of today, it would be difficult to contradict a similar analysis. Today, business spirit, multi-companies and the world of global tech giants are perfectly enmeshed in the ‘free and liberal’ West. The technical-industrial civilization standardizes. The ‘standard’ is the diametrical opposite of freedom.

What has actually happened is not the liberation of ‘man’ in the general sense, but the liberation of economics and materialism,

the replacement of the previous purpose of life (open to a transcendental freedom) with completely material and worldly purposes still called ‘liberty’ and ‘freedom’. All of this is accompanied by the loss of the idea of freedom in a higher, transcendental sense. ‘Freedom’ slowly becomes identical with ‘economic freedom’, just as it happens in the identification of ‘success’ and ‘business success’.

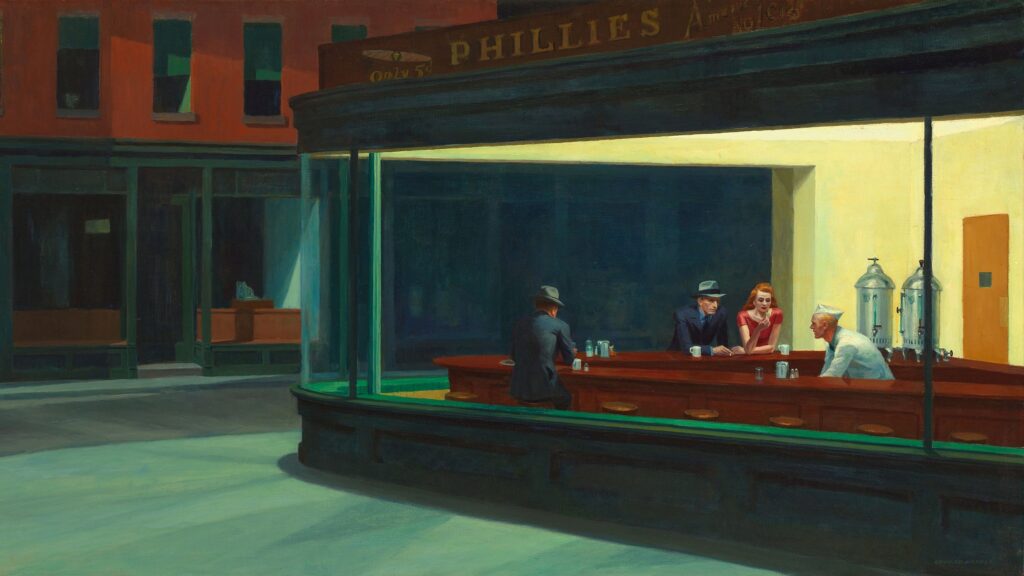

We could ask what this kind of approach ultimately does to the once transcendental human image.[7] The typical modern ‘consumer’—while still considering himself a ‘subject of freedom’ and sometimes a ‘religious person’—is driven by the desires whipped up by the system. As Chesteron writes: ‘a deadly fascination into the doors of a shop as into the mouth of a snake; that the subconscious is captured and the will paralysed by repetition; that we are all made to move like mechanical dolls when a Yankee advertiser says, ‘‘Do It Now’’’.[8]

The rock band Pink Floyd’s The Wall album, the beat generation and the hippie movement, the later punk, or even the left-wing criticism of capitalism in 1968 (cf eg Marcuse’s criticism of the ‘One-Dimensional Man’) were by no means unfounded. As the so-called liberal welfare capitalism began to take hold, the ‘not completely lost’ in the West urged to the return of the true and transcendental freedom, which was taken away from man by excessive rationalization and vulnerability to prosperity. However, the ‘Faustian bargain’ was already concluded by the ancestors. The new left-wing rebellions against capitalism, just as the Marxists’—without a real transcendental basis—had to drown in the waves of their own sea.

Although anti-capitalist conservative authors seem to be far from us in time (the 1890s, 1920s, and 1930s), what they describe and what they talk about—in terms of its main lines—is not at all something that is not true for the current development of the social and economic order, sometimes still called ‘capitalism’. However, today we are no longer talking about capitalism in the classical sense, and the focus of industrialized mass production is shifting in the direction of ‘digitalization’; still, the basic structures that build the economic and political worldview still seem eerily similar—throughout the ‘globalized’ world.

In the modern, global-technological civilization based on the parallel structures of technical rationality, the idea of freedom still arises as an ‘abstract freedom’ that is allegedly ‘the same for everyone’. But, regarding recent facts and conditions, this concept of freedom has lost all realistic content. Following the example of the idea of philosophical atomism, the human individual is still imagined as an atom, and from this social atomism it also follows that the modern individual is no longer an organ of a transcendental reality, but rather the social ‘whole’ is derived from this collective of individuals. According to the political logic of modernity, modern society is formed in a similar way as, for example, Leviathan in Hobbes’s theory emerges from the ‘voluntary’ association of all citizens. However, this social body is no longer an organism with a soul, but itself a technical leviathan, a cumbersome mechanism constructed by economic and industrial rationality. In short: a machine. The human and societal value is determined by the place occupied by each individual in the well-oiled operation of the social ‘big machine’.

We simply do not find the various well-known liberal attempts to define freedom in connection with the freedom ‘to something’ (positive) or ‘from something’ (negative) to be satisfactory when examining the essence of freedom.

The true concept of freedom is something deeper, broader and less relative

than we could express it in the sense of freedom ‘to or from’ something, and it is also closely related to the transcendental destiny by which the human individual is realized in the world of the human collective. This is not the freedom of Heidegger’s das Man, a freedom valid for an abstract general subject, but a spiritual task, that can be realized individually, and only by an intellectual-spiritual aristocracy.

As Jünger writes: even in the industrialized-economized modern world, the Forest exists, and there is a Forest Passage and a Forest Walker. Who is he? A Forest Walker is one who realizes that freedom from Leviathan is not only a matter of choice or no choice. He wants absolute freedom, which is also ‘a new concept of freedom’. The Forest Walker, however, is not an anti-establishment anarchist. He realizes freedom mainly internally, in his own soul, not the liberal economic freedom and not the freedom of the outlaw, the robber or the anarchist, but as transcendental (and at the same time, immanental) freedom. This means, above all, an internal and attitudinal separation from the spirit of modernity, its all-encompassing materialism, and its crippling commercialism. The symbol of the Forest is on the one hand the antithesis of Nietzsche’s ‘desert’[9], and on the other hand something that can be anywhere. Even the big city can be a Forest. The Forest is a symbol of primordial freedom, which means far more than free movement and economic and political independence. This is absolute freedom, understood in the sense of a higher intensity of existence. Inner independence from all the artificial desires and compulsions imposed on the Forest Walker, a freedom that shows a kind of Platonic idea: power. Not the freedom that can be expressed in some conceptual relation, but the idea, in se, the preservation of which is one of the most important conservative tasks.

[1] Ernst Jünger, Der Waldgang (The Forest Passage), Stuttgart: Klett-Kotta, 1980, 77.

[2] Jünger, Der Waldgang, 24.

[3] Hilaire Belloc: The liberal tradition. In. F. Y. Edgeworth (ed.) Essays in liberalism by six Oxford men, Casell and Company, London,1897, 1-31, 29.

[4] László Ottlik, A politikai rendszerek. In. A mai világ képe II. Politikai élet, 1939, 381.

[5] Ottlik, A politikai rendszerek, 382.

[6] Ottlik, A politikai rendszerek, 415.

[7] See for reference the biblical doctrine of ‘The man as Image of God.’

[8] Gilbert Keith Chesterton, The Outline of Sanity, Ihs Press, Norfolk, 96.

[9] Jünger quotes the words Nietzsche attributes to Zarathustra: ‘The desert grows: woe to him who harbours deserts!’ then adds: ‘Woe to him who does not harbour within him one single cell of that primal substance that ensures fertility, again and again’ (Jünger, Der Waldgang, 58).

Read more from Zoltán Pető: