This article was published in our print edition’s Special Issue on the European Union.

Ideas for Central European Cooperation in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries

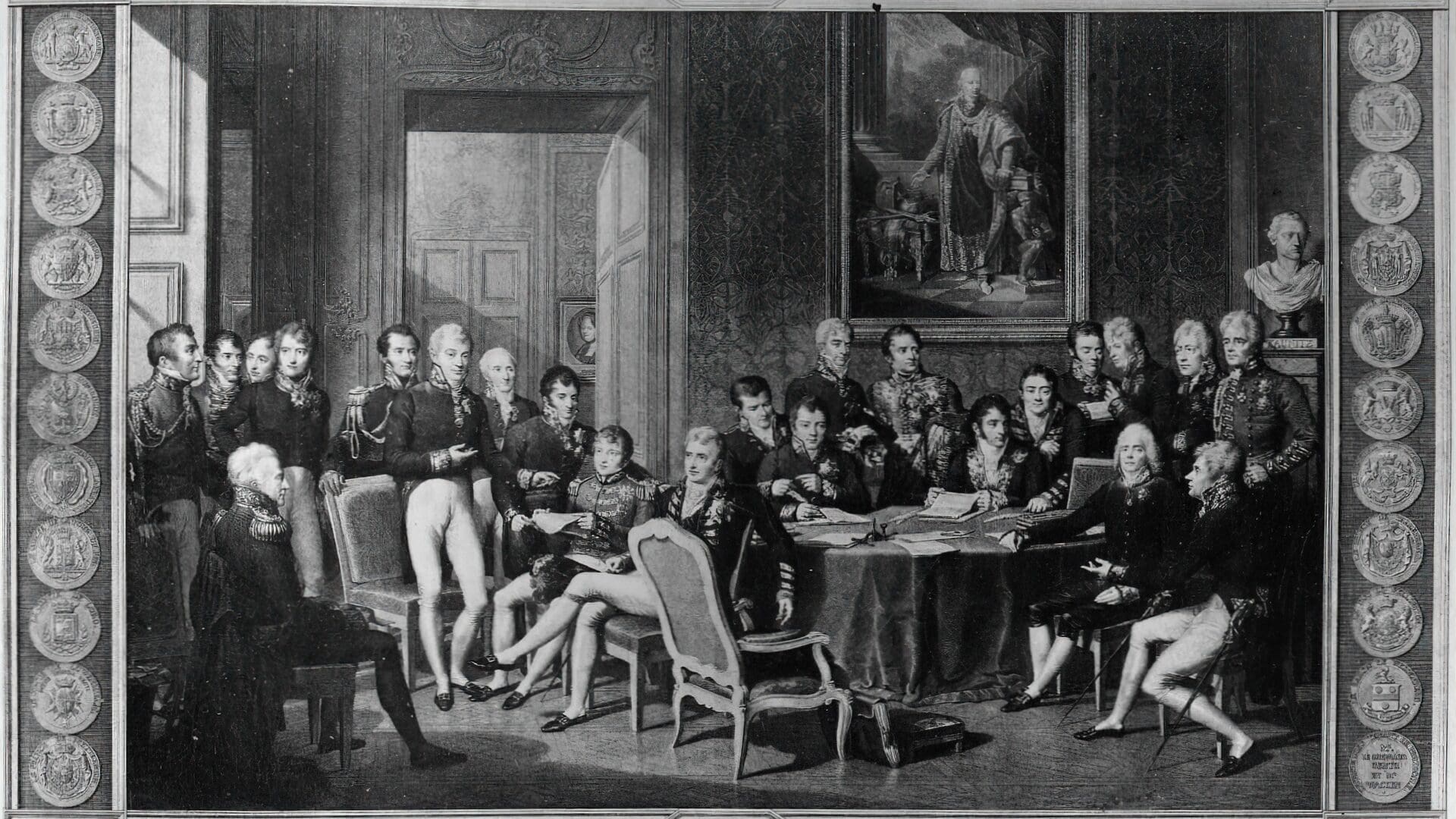

After the Napoleonic wars, on 26 September 1815, the political and military arrangement known as the Holy Alliance was concluded in Paris under the leadership of Tsar Alexander I of Russia, Emperor Francis I of Austria and King of Hungary, and Frederick III of Prussia, the countries controlling Europe’s destiny believed that the eighteenth-century model of state organization, social divisions, border issues, etc. could be preserved in perpetuity. However, the ideological models that had emerged at the turn of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (nationalism, liberalism, conservatism, socialism, etc.) had transformed social thinking and humanity’s view of the world to such an extent that it was impossible to maintain and preserve the earlier, semi-feudal Europe. This in turn meant that ethnicity and nationality, previously considered less significant elements—because the social status of an individual was primarily determined by the possession (or not) of a noble title, and by religious denominational affiliation—became a determining factor, leading not only to an exploration of the historical past of a given community, in the search for national heroes, but also to a demand for political unification with ethnic or linguistic compatriots within a single country. This aspiration resulted in serious difficulties and conflicts in European regions with ethnically mixed populations.

As for the Central European political elite, most believed that unified nation states could be created despite the ethnically mixed character of the region. A number of measures were implemented in confident expectation of success. In the Kingdom of Hungary, the major figures of the Reform Era, such as Lajos Kossuth, expected the liberation of the serfs to solve the problem of national minorities (such as the Slovaks, Ruthenians, Serbs, and the Vlachs, i.e. Romanians, etc.). In this view, the ethnic communities that comprised the lower social strata—i.e. those elements of the population without any title of nobility, who could be classified as serfs—would, out of gratitude for being made free peasants, become loyal to the Hungarian state, not desire territorial autonomy or wish to secede, and perhaps even embark on a path of voluntary assimilation. Others were open to the idea of forced assimilation, pointing to the example of the French Revolution (1789 and the events of the following years), which not only resulted in the birth of the modern French state, but also, due to the violent revolutionary circumstances, enabled the crushing of non-French national minorities within the country, and their forcible assimilation into the majority nation, in practice transforming the Kingdom of France into a unitary nation state.

‘The ideological models that had emerged at the turn of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries…had transformed social thinking and humanity’s view of the world to such an extent that it was impossible to maintain and preserve the earlier, semi-feudal Europe’

Few thinkers during this era devoted themselves to envisioning a confederal state that took full account of the multi-ethnic nature of Central Europe, or to planning concepts for regional cooperation. But who were the few who did, and what solutions did they arrive at? Without striving for completeness, this article intends to give a sense of these nineteenth- and twentieth-century plans and concepts.

The Plans of Polish Diplomat Adam Czartoryski

Adam Czartoryski (1770–1861) is a prominent and ambiguous figure in the history of nineteenth-century diplomacy. He is usually associated with efforts to re-establish Polish national independence, but at the same time, he was also concerned with the future of Central and Eastern Europe and the Balkans.1 During his years as Russian foreign minister and later in exile, Czartoryski developed a number of proposals for how the power of the weakening Ottoman Empire could be converted in the South-Eastern European region in such a way that, in addition to supporting national causes, a geopolitical environment would emerge in which the Russian Empire could be granted compensation and thus be willing to accept an independent Polish state in Eastern Europe.2 Czartoryski’s plans for the Balkans cannot be considered a classic ‘partition plan’, since he did not count on the complete disintegration of the Ottoman Empire, but he did consider the aspirations for independence among the peoples of the Balkans, and the principle of national self-determination, which in the eyes of his contemporaries was absolutely new.

The diplomat’s foreign policy career coincided with the beginning of the First Serbian Uprising and the start of Tsarist Russia’s active involvement in the Napoleonic Wars. In 1803, he developed his first major draft, A System for Russian Foreign Policy.3 His concept of Europe’s new political order, which he considered ideal for ensuring a state of equilibrium, was as follows: France should be pushed back to its own natural borders, and an Italian Republic should be created (comprising a union of Piedmont, Lombardy, and Venice), which would have a federalist character. The German states would become a federation, though without Austria and Prussia, and so would remain too weak to become a great power. His work also suggests a federation proposal for the Slavic peoples of the Balkans. Of the potential political units in the region, he considered only Greece as capable of creating an independent, functional state. He emphasized that if the Ottoman Empire were to break up, Tsarist Russia would have to play a key role in the reorganization of the Balkan region.4

In 1806, he again devised comprehensive plans for the Balkans. The starting point of his memorandum, drawn up in January of that year, was that, in order to protect the Adriatic region and the Mediterranean, Russia should ally with the greatest maritime power, Great Britain. He believed that an Anglo-Russian alliance should be re-established, with responsibilities divided between them: Russia would secure the Western and Eastern Balkans by protecting the Dalmatian territories and the Danubian Principalities (Moldova and Wallachia), while Great Britain would secure the Mediterranean and Egypt through its sea power.5

His second memorandum contained many elements not found in the previous one. Czartoryski prepared an independent action plan for Russian foreign policy in the Balkans, in which Russia, unlike in the previous memorandum, would not rely on an alliance with another great power. In addition to fending off French aggression, St Petersburg ‘must establish exclusive influence throughout South-eastern Europe’.6 In his opinion, the independence of the Balkan peoples should be supported, thereby increasing their dependence on Russia. As for the degree and nature of independence, Czartoryski considered a wide range of options. He would have left Serbia and Montenegro considerable autonomy, including even the freedom to choose their form of government. Moldova and Wallachia were at the other extreme, and he envisioned their wholesale absorption into the Russian Empire, making the Lower Danube the new frontier of the empire. Albania and Macedonia represented an intermediate situation, with the establishment of a predetermined, pro-Russian monarchical form of government.7

The central element of the third memorandum was the Western Balkans and the Greek region. Czartoryski believed that in order to take effective action against France, it would be absolutely necessary to win over Montenegro and Serbia, as well as to create two important buffer states. One would cover the Western Balkans through the union of Dalmatia, Montenegro, Cattaro (modern Kotor) and Herzegovina, while the other would be a Greek state born from the integration of the Ionian Islands and the Peloponnese, analogously to the re-establishment of Poland.8

The Hungarian Revolutionary Leader Lajos Kossuth’s Plan: The Confederation of the Danube States (Danube Confederation)

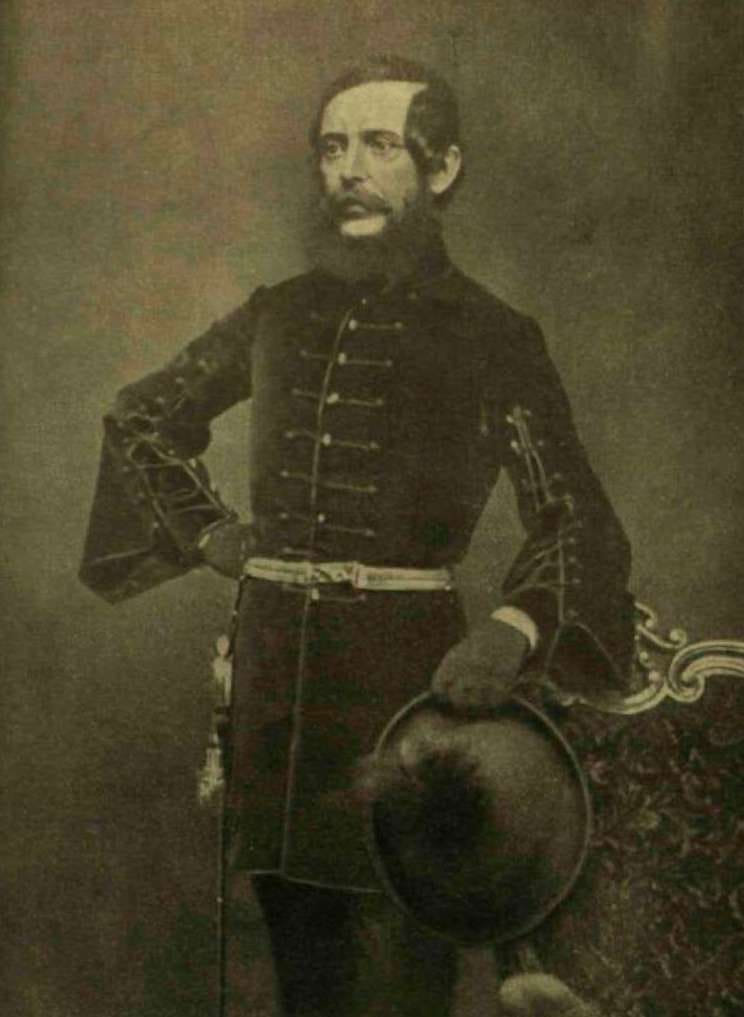

Lajos Kossuth (1802–1894)—in exile after the 1848–1849 Hungarian War of Independence had been crushed by the overwhelming might of Tsarist Russia—attempted to draw lessons from this experience. He came to the conclusion that one of the reasons for the failure of the War of Independence was that it had not been possible to bring the other nationalities over to the side of the Hungarians; they had not been persuaded that a Hungarian victory would be in their interests. Thus, altering the stance he had held during the Reform Era, he began to conceive of a confederation of states along the Danube, which would encompass not just the entirety of the Carpathian Basin, but also the homelands of some Balkan peoples such as the Serbs and the Romanians. Like Hungarian writer and statesman József Eötvös, he understood that it was no longer possible to create a centralized state in multi-ethnic Central Europe, so the needs of the region’s nationalities would have to be catered for to the greatest extent possible. He was equally convinced, however, that these small nationalities would never survive as independent states.9

Kossuth first outlined his plans for a confederation in June 1850, during a debate with fellow émigré László Teleki and Romanian revolutionary exile Nicolae Bălcescu, but he also covered the topic in his draft of the ‘Kütahya Constitution’,10 published in English in late 1851. Influenced by Kossuth’s views, his fellow émigré, General György Klapka (1820–1892), published a book on the Crimean War in 1855, in which he proposed to the Western European powers the restoration of Poland and the creation of a Hungarian–South Slavic–Romanian confederation, which would provide Europe with greater security against the Russian threat than Austria. In March 1859, in the service of French wartime diplomacy, he concluded an agreement with Prince Alexandru Cuza, which set the ultimate goal of cooperation as the confederation of Hungary, Serbia, and the two Romanian principalities.11

‘Most believed that unified nation states could be created despite the ethnically mixed character of the region’

In late 1861 and early 1862, the influence of Kossuth in the Italian government and among the underground resistance movement seemed to weaken, while that of Klapka grew stronger. The Italian government thus contacted Klapka for the first time, and on 15 April 1862 he prepared a thirty-point draft entitled ‘Programme for a Danube Confederation’. Subsequently, Marco Antonio Canini visited Kossuth, and on the basis of their discussion, Canini12 drew up a memorandum which Kossuth signed on 1 May, so that Canini could play a more important role in negotiations in the Balkans. Both men also swore to keep these discussions secret. Kossuth informed the editor of L’Alleanza, Ignác Helfy, about the plan (though off the record), but on 18 May, Helfy published the memorandum signed by Kossuth, under the title ‘Danube Confederation’. In the end, publication in L’Alleanza had the opposite effect to the one intended: it led to a break between Klapka and Kossuth, and thus to the permanent disbandment of the Hungarian government in exile, known as the Hungarian National Directorate.13 The draft was rejected by the Hungarian, Serbian, and Romanian sides. At the same time, the international environment was also changing: the Italian government cancelled its planned action, and Napoleon III dropped his plans for a war in the spring of 1863. Kossuth continued to stand behind the plan, publishing an exhaustive explanation under the title ‘Clarifications of the Danube Confederation project’ two weeks after the initial plans were published, and responding to objections received or likely to be received from the Hungarian side in several letters.14

According to plans for the Danube Confederation, the Kingdom of Hungary should enter into a union state with an independent Croatia and Transylvania, as well as Serbia and the Romanian (Vlach) principalities, which were then freeing themselves from Turkish rule, after the dissolution of the Habsburg Empire. The idea of a federal state was based on the principle of equality and close economic cooperation. Its common affairs (military and foreign affairs) would have been handled by the federal authority (government). The seat of government would periodically change between the respective capitals. The member states would preserve their internal autonomy (legislation, justice) and would mutually guarantee the rights of other confederal nationalities living in their territory.

Plan Published in 1906 by Romanian Politician Aurel C. Popovici

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the Romanian National Party abandoned the passivity that had previously characterized the party in national politics. In early 1905, the party manifesto was also rewritten to clarify its aims: from now on, they would fight for the rights of Transylvanian Romanians at all levels. The fact that significant personnel changes took place in the party leadership also contributed to this, and to all intents and purposes, a new generation took over. While the previous generation of ethnic Romanian politicians had tried to protest against the activities of Hungarian governments by withdrawing from national political life, the new, younger leadership group regularly appeared in the press, in many cases causing national scandals, and made full use of the most modern political methods of the era. They planned to increase support for the party by successfully conducting profile-raising actions. The Romanian National Party sought contact with Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and attempted to win his support.

In 1906, at the request of the ‘Workshop’ formed around Franz Ferdinand, who was known to be anti-Hungarian and inclined to support fundamentally transforming the dualist Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, the Romanian politician Aurel C. Popovici wrote a work that proposed transforming the dualist Austro-Hungarian state into a federation comprising many smaller units, which would also entail breaking up Hungary and Transylvania.15 As can be seen from his proposals, Popovici did not plan to base these federal units on historical but rather on ethnic boundaries, giving them a level of autonomy similar to that of member states of the USA. The Romanian-speaking citizens of Hungary would be given a state of their own—excepting an exclave in eastern Transylvania for the Hungarian-speaking Szeklers—and he hoped that Romanian unity could be achieved through the accession of the Kingdom of Romania under Habsburg rule. The plan undoubtedly sought to strengthen the dynasty, so the Workshop welcomed Popovici, who was so fond of Franz Ferdinand that he filled his apartment with portraits of the heir to the throne in various sizes. This despite the fact that his plan for a federalized Greater Austria was never fully accepted by Franz Ferdinand—though nor was any other programme proposed to him—and he later requested a conservative revision of the idea.

Hungarian Social Scientist Oszkár Jászi and the United States on the Danube

The First World War, or as contemporaries called it ‘The Great War’, ended with the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy on the losing side. Before the signing of the Trianon peace diktat in 1920, almost the last ‘amendment proposal’ was linked to the name of Oszkár Jászi. Jászi was president of the Civic Radical Party, founded in 1914, and handled minority affairs as a minister without portfolio in the Mihály Károlyi government that came to power on 31 October 1918. Jászi, who played a significant role in the road leading to Trianon, was given a task by the already completely impotent and naive Károlyi government which was—to quote the historian Gergely Bödők—‘mission impossible’.16 His negotiations, ideas, and attempts to persuade the national leaders who wanted to break away from Hungary seemed merely comical to his contemporaries. In his book entitled The Future of the Monarchy, he summarized his plan for an ‘Eastern European Switzerland’, by which he meant the federal transformation of the Austro-Hungarian state. He believed that by such means the empire could be saved, and that as a significant, independent cultural-economic region, it could successfully resist both German and Russian influence.

Jászi envisioned five state units to replace the Monarchy, uniting Austrians, Hungarians, Czechs, Poles, and South Slavs on the basis of equal rights and autonomy. This would have been a United States on the Danube. Jászi did plan to include Romanians, and would have kept Transylvania under Hungarian authority, but in other cases, he would have subordinated the historical Hungarian frontiers to ethnic realities.17

The Austrian Confederation Plan of Otto von Habsburg

Between 1934 and 1938, Otto von Habsburg, considered the heir to the throne in the eyes of legitimists, on several occasions discussed with Austrian Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg the possibilities of action against Nazi Germany. After Hitler issued a warrant for his arrest and the Nazis tried to kill him, he left Europe in 1940. When he reached the United States, President Franklin Roosevelt apparently listened with interest and sympathy to Otto von Habsburg’s idea of a democratized Habsburg confederation capable of stopping Germany in the future.18

Under the name of Otto of Austria, he summarized his ideas for a confederation in Foreign Affairs under the title ‘Danubian Reconstruction’, the essence of which was that the Habsburg Empire—though far from perfect—could have remained viable even after the First World War, and could be revived after the Second World War as a democratic confederation:19 ‘Many people today…are reluctant to undo past actions, because, as they say, “you can’t turn back the clock”. But there is another piece of wisdom which says that if one gets lost in the thicket, the best thing to do is to go back to where one left the trail.’20 At the same time, federalism ‘only helps to create a better world than that of 1919 if there is a strong central power that holds in its hands all decisions related to foreign policy, defence, international trade, and currency…This central power should be the main guarantor of the equality of nations…. We could borrow one of the foremost principles of the United States Constitution, according to which all member states, large and small, have the same number of seats in the Senate.21’

After the Second World War, Western Europe, then in ruins, and struggling with economic difficulties, realized that even in the eyes of the Western superpower, the USA, which offered and supplied loans for reconstruction, democratic Europe could only retain its ‘weight’ in world affairs if it succeeded in overcoming the historical contradictions and the events of the past to create a unified political entity based on economic cooperation. The Soviet threat in Eastern Europe also encouraged close cooperation. Based on these ideas, plans for the European Coal and Steel Community were born, followed by the European Economic Community, based on which the treaty establishing the European Union and financial union (the single currency) were established at Maastricht in the Netherlands in 1992. Meanwhile, in 1991, the Visegrád Declaration was signed by President Václav Havel of the Republic of Czechoslovakia, President Lech Wałęsa of the Republic of Poland, and Prime Minister József Antall of the Republic of Hungary.22 In 1993, with the split of Czechoslovakia, the Visegrád Group expanded from three member states to four, and the member states hoped that by cooperating they would be able to better assert their interests in world politics. All V4 member states became members of the European Union on 1 May 2004. The search for allies and the building of alliances continues today. Most recently, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán of Hungary said that although his country did not want to leave the V4, he could also envision the future creation of a Hungarian–Slovak–Austrian– Serbian regional alliance, which would be an ‘alliance of sovereigntists’.23

Translated by Thomas Sneddon

NOTES

1 Katalin Schrek and Gábor Demeter, ‘Adam Czartoryski Balkán-koncepciói’ (The Balkan Concepts of Adam Czartoryski), in Katalin Schrek and Gábor Demeter, eds, Az eszmetörténettől a nemzetközi kapcsolatokig (From the History of Ideas to International Relations) (Debrecen–Budapest: Debreceni Egyetem Történelmi Intézet, 2023), 85.

2 Schrek and Demeter, ‘Adam Czartoryski Balkán- koncepciói’, 85–86.

3 Schrek and Demeter, ‘Adam Czartoryski Balkán- koncepciói’, 86.

4 Schrek and Demeter, ‘Adam Czartoryski Balkán- koncepciói’, 87–88.

5 Schrek and Demeter, ‘Adam Czartoryski Balkán- koncepciói’, 92.

6 Schrek and Demeter, ‘Adam Czartoryski Balkán- koncepciói’, 92.

7 Schrek and Demeter, ‘Adam Czartoryski Balkán- koncepciói’, 93.

8 Schrek and Demeter, ‘Adam Czartoryski Balkán- koncepciói’, 93.

9 Krisztina Arató and Boglárka Koller, Európa utazása. Integrációtörténet (The Journey of Europe: A Story of Integration) (Budapest: Gondolat Kiadó, 2015), 42.

10 Kütahya (or Kiutahia) is a city in Türkiye. Lajos Kossuth lived here between the summer of 1850 and the spring of 1851. The above-mentioned draft constitution was also written here.

11 Gábor Pajkossy, ‘Az 1862. évi Duna-Konföderációs tervezet dokumentumai’ (Documents of the 1862 Danube Confederation Draft), in Századok, 136 (2002), 937–957.

12 Italian writer, activist, political agent. He participated in planning the so-called Balkan Confederation, to which Kossuth also contributed.

13 This was the leading body of exiled Hungarian political figures after the 1848–1849 Revolution and War of Independence, and the government in exile in 1859–1860. Its members were Kossuth, Teleki, and Klapka.

14 Pajkossy, ‘Az 1862. évi Duna-Konföderációs tervezet dokumentumai’, 938–939.

15 László Szarka, ‘A háborús paktumtól a keleti Svájc tervezéséig: A nemzetiségi kérdés az első világháború magyar kormányzati politikájában’ (From Wartime Pact to Planning an Eastern Switzerland: The Question of Nationality in the Hungarian Government Policy of the First World War), in Eruditio–Educatio, 11 (2016), 19–32.

16 ‘Trianon: így vajon egyben maradhatott volna Magyarország?’ (Trianon: Could This Have Been the Way to Keep Hungary United?), 24.hu (9 August 2020), https://24.hu/tudomany/2020/08/09/trianon100-igy-talan-egyben-maradhatott-volna-magyarorszag/, accessed 9 March 2024.

17 ‘Trianon: így vajon egyben maradhatott volna Magyarország?’.

18 András Schweitzer, ‘Edvard Benes, Eckhardt Tibor, Habsburg Ottó, Milan Hodza, Wladyslaw Sikorski konföderációs terve a második világháború idején’ (Edvard Beneš, Tibor Eckhardt, Otto von Habsburg, Milan Hodza, and Wladyslaw Sikorski’s Plans for Confederation during the Second World War), Doktorandusz hallgatók I. konferenciája, 2012. május 9. (Conference of Doctoral Students I, 9 May 2012) (Eger: Eszterházy Károly Főiskola Líceum Kiadó, 2013), 75–90.

19 Schweitzer, ‘Edvard Benes, Eckhardt Tibor, Habsburg Ottó, Milan Hodza, Wladyslaw Sikorski konföderációs terve a második világháború idején’, 80.

20 Schweitzer, ‘Edvard Benes, Eckhardt Tibor, Habsburg Ottó, Milan Hodza, Wladyslaw Sikorski konföderációs terve a második világháború idején’, 80.

21 Schweitzer, ‘Edvard Benes, Eckhardt Tibor, Habsburg Ottó, Milan Hodza, Wladyslaw Sikorski konföderációs terve a második világháború idején’, 80.

22 Romania was originally supposed to participate in this collaboration, but due to the anti-Hungarian atrocities in the country, President Ion Iliescu finally announced that his country would not participate.

23 Hecker Flórián, ‘Magyarország új szövetségeseket keres: Orbán Viktor bejelentette, milyen országokkal képzeli el a jövőt’, Világgazdaság (4 March 2024), www.vg.hu/kozelet/2024/03/magyarorszag-uj-szovetsegeseket-keres-orban-viktor-bejelentette-milyen-orszagokkal-kepzeli-el-a-jovot.