This article was published in our print edition’s Special Issue on the European Union.

The social teaching of the Roman Catholic Church (socio-theology) is built on three main principles. The most important is human dignity (dignitas humanæ): it is based on the notion that every human being is made in God’s image (imago Dei), and this leads to personalism. The second principle is solidarity (solidaritas): that is, a firm commitment towards the common good (bonum commune). The third is subsidiarity (subsidiaritas)—and this paper is about this third principle.

Lowest Competent Authority

As a politological principle of organizing society, subsidiarity can be defined as the requirement that issues should be dealt with by the lowest competent authority. Of course, there are issues of high importance where the lowest competent authority is the state (or the federation) itself, but beforehand there is a need for a thorough examination of whether that is truly the case. Etymologically, there are three possible sources of the expression. In Latin, subsidere means to aid, to help, to assist, as well as to relieve. Thus, the function of a central entity or authority towards the lower levels of society is at best merely subsidiary. Second, subsidium, as an ancient Roman military term, referred to a unit that was to sit behind (subsidere) during a military confrontation, lending support only in case of need or emergency. A third possible source might be sub-sidere (to settle down): i.e. to seat or settle a service in the society as close to the emerging need as seems possible and feasible.

‘The principle of subsidiarity is widely used in the European Union, where it means the following: decisions should be taken at a higher level where necessary, and at a lower level wherever possible’

Federalism as a Playground

In political science, subsidiarity is closely linked with questions arising from federalism. In a federal environment, competences can be exclusive to the federation or union, or shared among the federation and the states, or the federation may limit itself just to support the states in making decisions. A minimalist view of state interventionism (close to the views of libertarians) would be that the state defends the whole community, protects the rights of its citizens, and upholds a just social order. Proportionality thus demands only the bare minimum of actions that are necessary: the final decisions on a given issue must be taken as closely as possible to the citizens. In this sense, the principle of subsidiarity is widely used in the European Union, where it means the following: decisions should be taken at a higher level where necessary, and at a lower level wherever possible. The reason for its widespread usage is the fact that the EU has become a prime example of a federalist (or quasi-federalist, intergovernmentalist) organizational method, a playground packed with all the problems and debates springing from federalism.

A Principle of Catholic Social Teaching

However, in this paper we shall limit ourselves only to the socio-theological use of the concept. It seems that the concept comes from two sources simultaneously: one Roman Catholic and the other Protestant (Calvinist). Among the Roman Catholic social thinkers, three names emerge—two of them Jesuits—as key to the concept of subsidiarity: Luigi Taparelli, Wilhelm Ketteler, and Oswald von Nell-Breuning.

Luigi Taparelli SI (1793–1862) was an Italian Jesuit (but educated by the Piarists), who concentrated his theoretical efforts on finding a just social order on the bases of natural law.1 During his research, he not only coined the term ‘social justice’, but also elaborated upon subsidiarity. He played a key role in reviving Thomism (the teaching of Thomas Aquinas OP, 1225–1274). Taparelli does not subscribe to conflict and competition in society: according to him, it would be erroneous to base our social understanding on these. Rather, he sees society as a conglomerate of different levels of sub-societies, which naturally have both rights and responsibilities (duties) to fulfil. The role of the state is to recognize the operation of these levels, support them, and help them to cooperate in a rational way. Thus, it is obvious that subsidiarity for him makes sense not only in federalist circumstances, but also in a single, multi-level society.

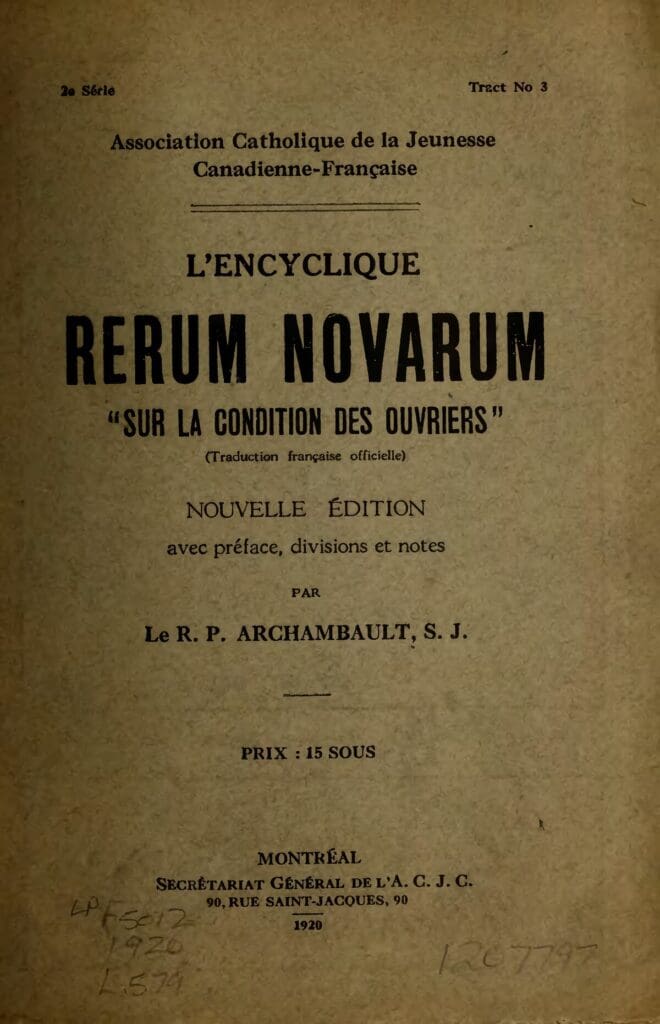

Taparelli was not the only thinker whose writings were highly influential for the social teaching of the Church, especially on Rerum novarum (1891), an encyclical of Pope Leo XIII. Another important contributor to Catholic thinking on subsidiarity is Wilhelm Ketteler (1811–1877), a bishop of Mainz.2 For his contribution, he is cited in Deus caritas est (2005), the first encyclical of Pope Benedict, underlining his role in socio-theology, including the principle of subsidiarity. Long before the birth of the ecumenical movement (1895), he insisted on reconciliation between Roman Catholics and Protestants, especially in matters of state and politics.

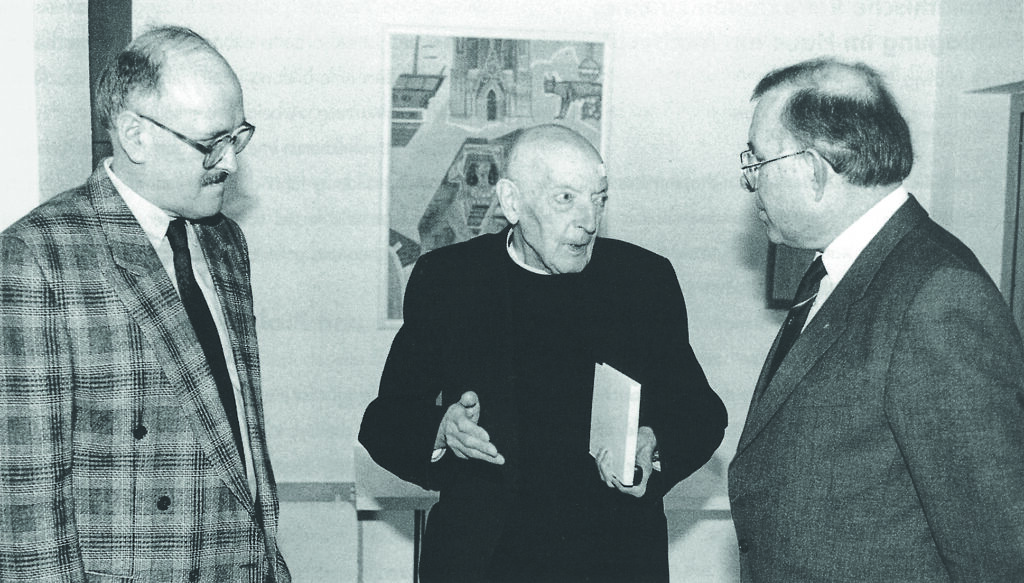

Oswald von Nell-Breuning SI (1890–1991), meanwhile, was a German Jesuit and a central figure in drafting Quadragesimo anno (1931), an encyclical of Pope Pius XI, the very document in which the word ‘subsidiarity’ first appears, and in which we find the Roman Catholic definition of the principle.3 He was also influential in the merging of Roman Catholic and Protestant Christian Democracy in Germany after the Second World War.

Sphere Sovereignty in Protestantism

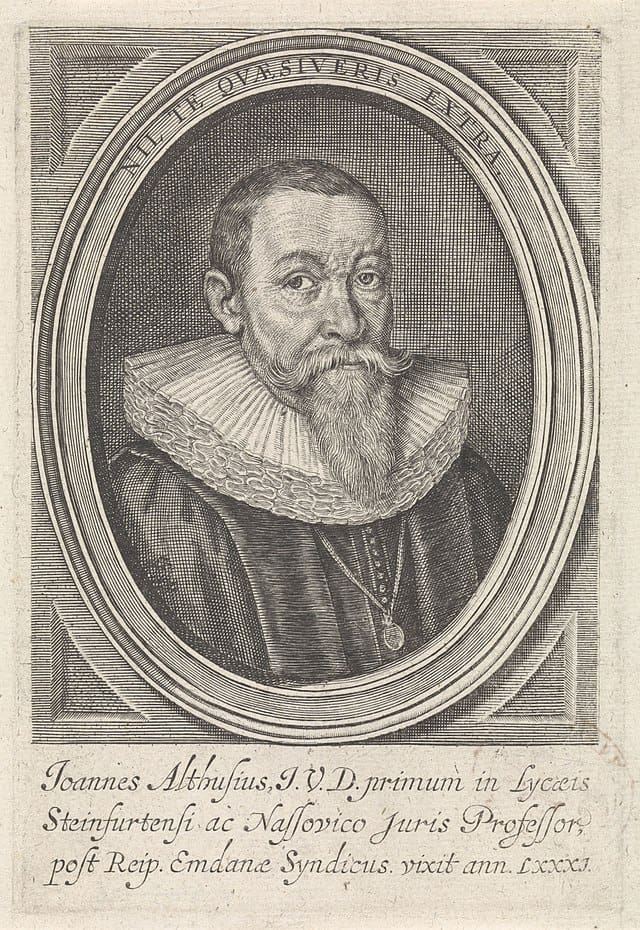

The parallel Protestant line of thought has two sub-tracks: one uses the word ‘subsidiarity’ (especially Johannes Althusius), the other prefers the notion of ‘sphere sovereignty’ (as employed by Abraham Kuyper during his prime ministership). The first key figure in this Protestant line of social thought is Johannes Althusius (1563–1638), a Calvinist legal thinker, and in his main work, Politica Methodice Digesta (1603), he dealt with questions of federalism.4 He produced the first full concept on this topic, and might thus rightly be called one of the fathers of modern federalism. While elaborating its principles, and trying to defend local autonomies, he developed the idea of subsidiarity. In his view, confederations must be cooperative social orders, built on various levels of political communities. Naturally, these all pursue their own interests, but because they are cooperating, they also pursue common interests, the common good. Such a society becomes a community of communities, living in a kind of symbiosis (consociatio symbiotica). In such an order, power is not to be surrendered to the state, but to be shared responsibly among the actors. Althusius was a contemporary of Jean Bodin (1530–1596) and challenged the latter’s idea of sovereignty as belonging solely to the ruler. Althusius believed that real sovereignty had to rest with the community itself, in the form of subsidiarity.

A neo-Calvinist concept parallel with subsidiarity is ‘sphere sovereignty’: it holds that sovereignty neither belongs to the people (as in France in the nineteenth century), nor to the state (as in Germany in the nineteenth century). Instead, the idea is that each sector in society is equal: all have their own duties and responsibilities, and in relation to these, their own competences, giving them their integrity and authority. The separation of church and state is a prime example of where separate spheres can be sovereign or autonomous.

‘Subsidiarity…calls for a healthy society, where different vertical levels and horizontal spheres respect each other’s autonomy, even sovereignty, while at the same time bringing them into cooperation’

The person who first implemented sphere sovereignty in practice was Abraham Kuyper (1837–1920), a Protestant pastor and prime minister of the Netherlands (1901–1905).5 He held that each part of human life exists before the face of God (existentia coram Deo), and thus the state and other spheres in human society must be separated. According to him, all these societal spheres are sovereign: they are beyond the control of the state, or for that matter of the Church: these important institutions should not interfere in the internal affairs of other spheres. As a politician and statesperson, Kuyper applied his principles to society, creating the Christian Democratic idea of ‘pillarization’ in the Netherlands. His Christian Democracy created an alliance between Roman Catholic and Protestant social doctrines.

Decentralization and Distribution

An important economic aspect of subsidiarity is distributism, a middle way between laissez-faire capitalism and state socialism, the two extremes of economic thinking. And this is exactly the niche in which Christian Democracy, with its social market economy, can find its proper place. What distributism aims to distribute is property ownership, since it sees right to property as a fundamental human right. Instead of centralizing the means of production in the hands of the state (statocracy), corporations (corporatocracy), or a handful of people (plutocracy), they are to be decentralized and distributed. Distributism recommends family, societies, associations, and cooperatives as the centres of ownership. The first two papal encyclicals (Rerum novarum, Quadragesimo anno) on Roman Catholic social teaching both serve as a basis for distributism. Two important Roman Catholic names associated with this interpretation are Hilaire Belloc (1870–1953) and Gilbert Keith Chesterton (1874–1936).

Quadragesimo Anno (1931)

In Leo XIII’s Rerum novarum (1891), all the elements for proclaiming subsidiarity were ready, but it took another forty years for the papal teaching authority to use the word itself, and to give it a proper definition.6 We cannot forego quoting one important paragraph of Quadragesimo anno (1931) for its significance not only for Roman Catholics, but for Christian Democrats in politics as well:

‘Just as it is gravely wrong to take from individuals what they can accomplish by their own initiative and industry and give it to the community, so also it is an injustice and at the same time a grave evil and disturbance of right order to assign to a greater and higher association what lesser and subordinate organizations can do. For every social activity ought of its very nature to furnish help to the members of the body social, and never destroy and absorb them.’7

One notices in the text at least two sets of vertical opposites: individual and community, as well as lesser organization and higher association. According to the spirit of socio-theology, these elements are not in a state of class struggle, but are called upon to cooperate, to work together effectively. Subsidiarity is the principle that organizes their cooperation.

There is indeed a hierarchy among them, but this hierarchy is the opposite of what one would expect: instead of the priority of power, the logic of subsidiarity follows the priority of the person, the local, the familiar. This emphasis flows from the philosophy of personalism, which permeates all Catholic social teaching.

The state (or federation) is not mentioned explicitly in the text quoted, but we can include it in the category of higher associations. Indeed, it is extremely important to have a strong middle level (‘society’) between individuals and the state. They enhance the life of the person lived in accordance with her or his human dignity, and serve as protection from any possible preponderance of the state.

Types of Subsidiarity

In modern Christian Democracy, the Roman Catholic and Protestant lines of thought come together to form a common Christian understanding of a desirable society. Subsidiarity as one of the core principles in social teaching calls for a healthy society, where different vertical levels and horizontal spheres respect each other’s autonomy, even sovereignty, while at the same time bringing them into cooperation. When subsidiarity is properly applied in a society, the public (state) sphere and private (individual) sphere are in a correct balance. To summarize the concept, we can distinguish between static and dynamic, vertical and horizontal, as well as negative and positive subsidiarity.

First, subsidiarity has a static and a dynamic side. In its static meaning, it sets and defines priorities among the levels of society. In its dynamic form, its calls for the intervention of the higher level, which is to furnish help in the case of need. But even this dynamism is governed by the essence of subsidiarity: the intervention must, whenever possible, be exceptional, temporary, interim, transitory, and its aims should always be empowerment, not weakening—service, not domination. The criterion which helps decide about regularity or exceptionality in each situation is the common good.

Second, we may thus distinguish between a vertical and a horizontal dimension of subsidiarity. The vertical dimension concerns the upside-down hierarchy among the levels of society elaborated so far, and the horizontal dimension is connected to the notion previously referred to as sphere sovereignty. This second requirement calls for a legitimate diversity of the various social spheres, to be at least semi-autonomous among themselves.

‘When subsidiarity is properly applied in a society, the public (state) sphere and private (individual) sphere are in a correct balance’

Finally, since the state is the most powerful actor in the scheme, it has a double responsibility when it comes to implementing subsidiarity, one negative and one positive: In a negative way, the state is bound to refrain from interfering in the affairs of lower levels and the various spheres in society—except when absolutely necessary. And as a positive duty, the state must provide the social and legal conditions necessary for subsidiarity to be implemented: first and foremost keeping in mind the full development of the whole human being.

NOTES

1 For an excellent monograph on Taparelli and the notion of subsidiarity, see Thomas Behr, Social Justice and Subsidiarity: Luigi Taparelli and the Origins of Modern Catholic Social Teaching (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2019).

2 For an article on Ketteler and subsidiarity, see Martin J. O’Malley, ‘Currents in Nineteenth-Century German Law and Subsidiarity’s Emergence as a Social Principle in the Writings of Wilhelm Ketteler’, Journal of Law, Philosophy and Culture, 1 (2008), 23–53.

3 On his experiences as the first drafter of the document, see Oswald von Nell-Breuning, ‘The Drafting of Quadragesimo Anno’, in Charles E. Curran and Richard A. McCormick, eds, Readings in Moral Theology No. 5: Official Catholic Social Teaching (New York: Paulist Press, 1986), 60–68.

4 For a good summary on Althusius, see Ferenc Hörcher, ‘Overcoming Crisis in an Early Modern Urban Context: Althusius on Concord and Prudence’, in Cesare Cuttica, László Kontler, and Clara Maier, eds, Crisis and Renewal in the History of European Political Thought (Leiden: Koninklijke Brill, 2021), 214–234.

5 On his life and work see Ádám Darabos, Abraham Kuyper (1837–1920), in Ádám Darabos and András Jancsó, eds, Theologians on Modern Politics (Budapest: Batthyány Lajos Foundation, 2023), 63–68.

6 On the great pope and his social encyclical see András Jancsó, ‘Pope Leo XIII (1810–1903)’, in Ádám Darabos and András Jancsó, eds, Theologians on Modern Politics (Budapest, Batthyány Lajos Foundation, 2023), 13–21.

7 Pope Pius XI, Quadragesimo anno, Encyclical, 1931, www.vatican.va/content/pius-xi/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_p-i_enc_19310515_quadragesimo-anno.html.