The following is a translation of an article written by Zita Meszleny, originally published in our sister publication Magyar Krónika.

A simple, self-sustaining life. This is what they wanted, and thanks to coincidence, they made their way from Belgium to Rönök in the Őrség region* of Hungary, where they could create such a life for themselves. Jan Leen and Wijnants Wouter raise children, make cheese, keep animals, and tend a garden at the Szedervirág (Blackberry Blossom) Organic Farm. But most importantly, they live happily. Read Magyar Krónika’s conversation with the couple below!

This Is How They Arrived in Hungary

There is no school, kindergarten, pub, and no house numbers one, four, or six—only number five, as it is. The former hamlet on the outskirts of today’s Rönök found itself in the borderland in the middle of the last century. The civilian population was facing forced relocation, and the homes of the local s fell into ruin. The latter are now replaced only by a few piles of rocks—the characteristic Őrség nature reconquered the land. However, the decades of muteness of the deceased village were broken in 2009 by unexpected Flemish speech.

In their early twenties, in the doorway to a life together, or rather to their camper, Leen and Wouter from Belgium decided not to settle down in their hometown, but to look for a new home and a new way of life. ‘We couldn’t have bought property in Belgium, but we didn’t even want to. We lived in a settlement of fifteen thousand people, called a ‘village’ there, where a flower box on the pavement meant ‘nature’. My father worked in insurance, I felled dangerous trees, and Leen studied fashion design. We had nothing to do with farming, yet we were attracted to the idea of a self-sustaining life. We had a small garden in front of our camper where we grew lettuce and dreamed of doing it in a bigger, more normal way. From there it’s not a very romantic story. We searched the internet for cheap land and found Hungary. We honestly didn’t know anything about the country, but we looked it up, and after a month we travelled here and bought this five-hectare property with a ruined house on it for a few thousand euros. The whole process took five weeks. We changed countries and swapped the concrete jungle for real nature,’ says Wouter, with every sentence more and more confidently in Hungarian, while showcasing the family of four’s self-sustaining estate, the Szedervirág Organic Farm.

‘We were lightheaded and naive,’ he admits.

‘This was the only site we looked at. Not only did it not occur to us that a completely different language was spoken here, but we only checked if there was drinking water after the contract had been signed. Still, perhaps we were lucky not to have thought about it.

If we had considered everything, we might not have dived right in. If you ask why we chose to make our dream come true in the Őrség, the answer is that luck or fate guided us.

That’s all there is to it.’

Experimentation

‘Toilet paper and grain,’ is Wouter’s surprisingly brief reply when asked about what they have to buy, even though the goal is self-sustainability. ‘Tomatoes, peppers, marrows, pumpkins, onions, leeks, beans, peas, maize, beetroot, lettuce, chicory, carrots, kohlrabi…’ is his endless list of answers to our question about the treasures of their vegetable garden. The hens provide the eggs and the cows the dairy products, but the family does not eat meat. They go shopping once a month, electricity is provided by solar panels and water by a well. But as they needed some money, especially when they started out, the couple attempted hospitality for a while. They built two guesthouses out of wood and clay, as there is no shortage of these two materials on the farm. ‘I heard that the way to build a house is to put one brick on top of the other. I experimented. Then, when the woodworms ate the roof, I learned from my mistake and rebuilt it. By the time I finished our new family house last year, at least I had some experience,’ the farmer says, shrugging his shoulder and showing the huts, which look eerily similar to the hobbit huts of Middle-earth.

Then the curious tourists came. However, it soon became clear that, although most of them were keen to hear the birds chirping, were less enthusiastic about the early morning crowing, and while they were happy to watch the idyllic image of calves chewing their cud, were no longer so thrilled to see the cow dung. ‘Moreover, we came here for silence and peace, and suddenly we were surrounded by strangers again,’ recalls Wouter. When they realized that hospitality and farming were difficult to reconcile, they decided to earn the necessary income from the latter, more specifically from cheese-making.

‘We started with two goats because we were afraid of bigger animals. They were good to practice with. Then came the cows. First, we got smaller ones, jersey cows, then we got brave and bought Hungarian Simmentals. Three years ago, there were only four of them, now there are eleven. But I’m still a little afraid of the biggest one,’ he recounts, as he heads towards the family home, watching his animals make their way towards the huge barn he has built as 7 o’clock approaches.

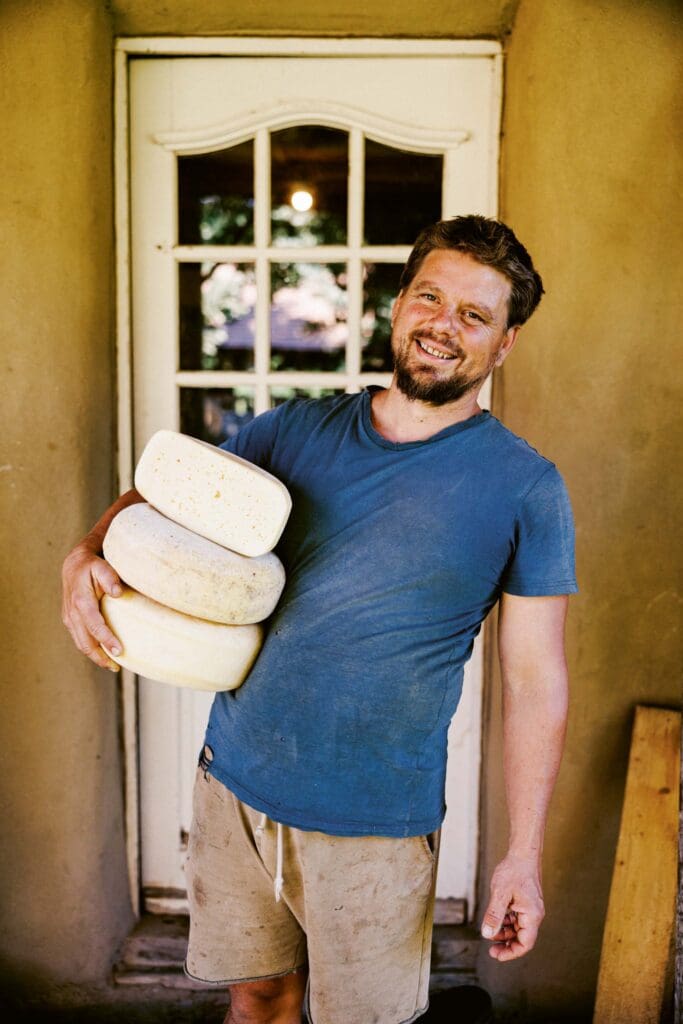

The cows roam the property all day long, but they cannot wander just anywhere. The couple believes in paddock grazing. The property is divided into forty smaller meadows, and every day the cattle are moved from one to another so that by the time they have gone around the whole property, the herb-rich lawn has been renewed. Quality grass, calm animals, decent conditions—that is the secret of perfect cheese, according to the farmer. And we, after indecently quickly consuming the slices we taste, would believe anything he says about cheese. It is not surprising at all that their products are purchased by the best restaurants and that they don’t even need to go to market anymore, as their reputation attracts enough customers to their doors. Seventy to eighty kilos a week would run out several times that. If they could take it. Or if that was the goal. But it’s not.

Simple Answers

Two blond children, one and a half and three years old respectively, are playing near a makeshift pool in front of the fairy tale family house. ‘Two minutes of idyll,’ smiles Wouter. ‘And it’s over,’ laugh Leen and her husband as they try to stop Frida and Emil who have started fighting in the meantime.

‘It’s interesting that I never thought about having children in Belgium. Life was so different there. It was a grinder where I never thought I would miss having a child. The desire for a family was only born in me here,’ says the mother after the heat dies down. We learn that their children, who already speak Hungarian, English, and Flemish, will be home-schooled. ‘I hope that learning will be a natural process for them, that they will absorb the knowledge, just like absorbing the three languages,’ explains the father, but then quickly adds that community is important as well. They don’t want to isolate them in any way. ‘We just think eight hours in an institution is too much stimulation for a young child.

Watching how nature works, how children play, or how our destiny unfolds, I learn every minute that life should be simplified, not overthought.

Because I am a worrier. For the last ten years, we have been trying to catch up with ourselves. Even now, there is still a lot to do; we would need a workshop, a milking parlour, a cheese kitchen, and a shop, but now I can stop if needed and just be happy. Accept that tomorrow is another day, and work can wait. However, plans are needed. A friend of ours, a hoof trimmer, told us that farms where farmers say they are ready start to die in a short time. It’s terribly boring to get up, milk, and manure and not know anymore why you’re doing it. So we have goals that inspire us, that keep the farm alive,’ concludes the husband.

Milking and bedtime are almost here. The children say goodbye to the cows waiting for their turn and together they put the hens in the barn. Wouter watches with palpable satisfaction at this heart-warmingly ordinary scene, born from a daring dream. We wonder if this is the life they imagined back then, in that camper. ‘What happened to us here is unimaginable,’ he replies. Then we ask them if after fourteen years and so many experiences, they feel more Belgian or more Hungarian now. He responds thoughtfully, ‘We? We feel happy.’

*Őrség lies in the south-west corner of Vas County, in the vicinity of Austria. Already at the time of the Hungarian conquest, frontier guard communities were given land here to protect the country, hence the name, which means ‘Guard’ in Hungarian.

Related articles:

Click here to read the original article.