After the fall of the medieval Kingdom of Hungary in 1526, the country was divided into three parts. From then on, the Turks were present in the Carpathian Basin remained until the end of the 17th century—the Ottoman Empire was driven out of the Balkans only in the late 1600s. The Holy See forged the Holy League in 1684, with the Habsburgs, the German principalities, Venice, Poland, and later Russia. To ensure the success of the alliance to expel the Turks, the Kingdom of France declared neutrality.

In 1686 the Christian forces liberated Buda, and then achieved successes in Transdanubia and on the Danube–Tisza Interfluve, recapturing the cities of Pécs and Szeged. In 1687 the Ottomans suffered a heavy defeat at Nagyharsány and the imperial troops invaded Transylvania. Then in 1688 Nándorfehérvár (today’s Belgrade, Serbia) also fell into Christian hands. When Louis XIV, seeing the Habsburg successes, launched a new war towards the Rhineland, and the Supreme Command in Vienna removed its troops from Hungary, it seemed that

the opportunity for the Hungarians to regain their independence had arrived.

However, appearances can be deceiving. After the expulsion of the invading Turks, the Viennese court took measures that made the Hungarians rightfully suspect that the Turkish occupation had been replaced by Austrian occupation. After the decisive defeat of the Ottomans at Zenta (today’s Senta, Serbia) in 1697, and the conclusion of the Treaty of Karlóca (today’s Sremski Karlovci, Serbia) in 1699, in which the Turks acknowledged the loss of the Ottoman Empire, the imperial generals decided the fate of the reconquered country on the basis of the right of the victor. Leopold I also took advantage of the military successes to persuade the Hungarian estates to give up the right to freely choose their king and to abolish the resistance clause. Thus, the Habsburg Dynasty secured rule over the Kingdom of Hungary legally.

The Principality of Transylvania was placed under the control of Vienna in 1691, while the other liberated parts of the country were placed under their own administration through the New Settlements Committee. This meant that Hungarian noble families had to prove their ownership of an estate by means of old deeds, many of which had been destroyed in the turbulent centuries that had passed. Even if they did succeed, they could only get their property back on payment of a fee of 10 per cent of the estimated value of the estate. At the same time, the estates which their rightful owners were unable to reclaim as aforesaid, were given to the army’s chief officers and munitions suppliers as payment. The prolonged military operations entailed considerable costs, which Vienna passed on to the serfdom.

The dismissed soldiers,

unable to recover their lands, suffering under huge taxes, and once again persecuted for their Protestant faith,

hoped to organize a kuruc movement and revolt against the Habsburgs.

It is also important to note that the increasingly obvious absolutist ambitions of the Habsburgs may have also aroused nostalgia in contemporaries for the past century of Ottoman presence.

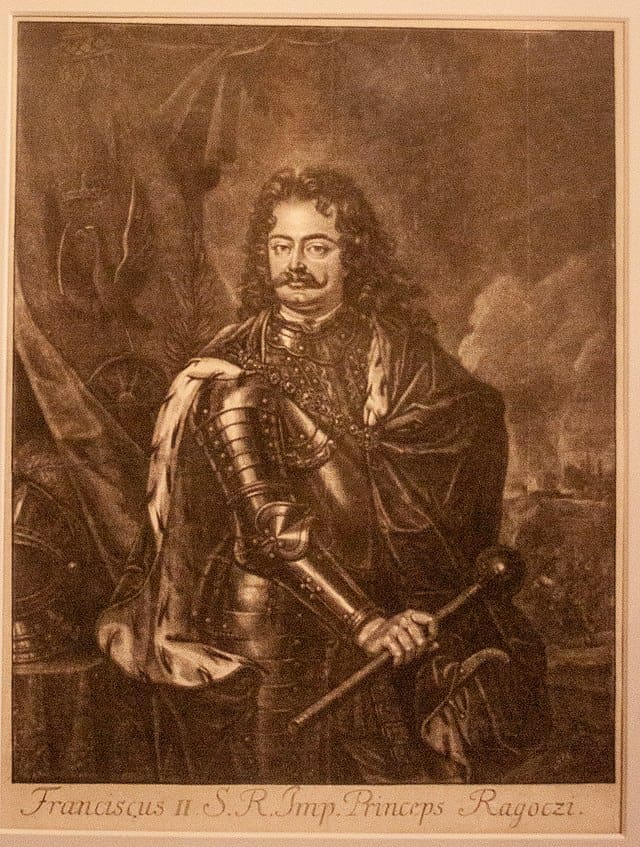

Those who opposed the rule of Leopold I put their faith in Ferenc (Francis) II Rákóczi. But who was he in whom the Hungarians placed so much trust?

Rákóczi was born in 1676, in the Borsi Castle in Zemplén County. His father, Francis I Rákóczi, was the elected Prince of Transylvania, an active participant in the so-called Wesselényi Conspiracy against the Habsburgs, and his mother was Ilona Zrínyi, daughter of the Ban of Croatia, Péter Zrínyi. He was three months old when he lost his father, after which his mother married Imre Thököly, a kuruc general of the Lutheran faith who was also hostile to the Habsburgs. The widowed Ilona Zrínyi fled with the family’s valuables to Munkács (Mukachevo, Ukraine) to escape the approaching imperial troops, and she and her children were confined there. She withstood the imperial siege for two and a half years, but on 17 January 1688, after long negotiations, she was forced to surrender the castle. The Habsburg revenge did not fail to come: the family had to leave the country and could not keep their estates. Ilona Zrínyi had to move to Vienna, where her daughter Julianna was imprisoned in the monastery of the Ursulines, while her son Francis was sent to the Jesuit college in Neuhaus, Bohemia. The aim was to turn all the members of the family into devout Catholics and loyal to the Habsburg court. In 1692 his custodians summoned Francis II Rákóczi to Vienna and he was declared of full age. This was necessary so that the Rákóczi estate could be used to pay out his sister’s legal inheritance, the ‘daughter’s quarter’.

In 1693 he spent a year in Rome, and immediately after his return he went to his estates in Hungary. After being installed in the office of the count of Sáros County, he married Princess Charlotte Amalie of Hesse-Wanfried. They had three children, Leopold, Joseph, and George. Despite his pro-Habsburg upbringing, when he returned home he realized all the problems that the Hungarian people had to contend with under the Habsburg yoke.

In 1700 he contacted the French Emperor Louis XIV through the French ambassador to Poland, who would not even have been averse to financial support in the event of a domestic uprising against the rival Habsburg Empire. However, the correspondence with the French King became known to Vienna too, for which Rákóczi was arrested and imprisoned in the Wiener Neustadt Prison in 1701. He escaped the certain sentence of death in an adventure story-like manner with the help and support of his wife and influential court figures. After fleeing to Poland, Francis did not stop to make diplomatic efforts also in exile to win the support of the Kingdom of France.

Two important events played a role in Rákóczi’s return to Hungary in 1703. On the one hand, the unfolding War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714), which meant the withdrawal of most of the imperial regiments from the country, and on the other, the uprising of the serfs of Munkács, provided the perfect opportunity for Rákóczi to organize an armed rebellion. At the request of Tamás Esze, the leader of the uprising in the Tiszahát region,

Francis II Rákóczi took the lead in what developed into a War of Independence, issuing a proclamation calling on nobles and non-nobles alike to take up arms

—thus avoiding the possibility of anyone making the uprising look like a mere peasant uprising. The appeal in the Brezán (Berezhani, today Ukraine) Castle set out the causes and political aims of the uprising. Two possibilities seemed to be outlined: the dethronement of the Habsburg Dynasty, the restoration of the elective kingdom in Hungary and the election of a new king, and the independence of Transylvania; or, if the first was not feasible, the restoration of the old rights of the Kingdom of Hungary, the redress of grievances, and the recognition of the independent Principality of Transylvania by the Habsburg ruler.

Although the troops of the so-called Tiszahát uprising led by Sándor Károlyi were crushed by the noble banderiums, Rákóczi took up the fight despite the unfavourable omens. He united the interests of the nobility and the serfs with great tact and determination, and in a very short time, he organized the makeshift, poorly armed kuruc troops into an adequate force. By the end of 1703, a large part of the country (the Transtibiscan region, the Danube–Tisza Interfluve, and Upper Hungary) had fallen under the control of the kuruc, with the nobility joining the movement en masse. So did Sándor Károlyi, who, after his defection, pushed forward with his troops as far as Vienna.

Naturally, the prospects for the struggle for freedom were greatly influenced by the events of the wars going on in Europe. In 1704 when the defeat of the Franco–Bavarian armies at Blenheim-Hochstädt deprived Rákóczi of direct help from the West, the Diet of Gyulafehérvár (today Alba Iulia, Romania) elected him Prince of Transylvania. Then, with Dutch and then British mediation, peace negotiations between Rákóczi and the Habsburgs began as early as 1704. In the meantime, at the Diet of Szécsény in 1705 the alliance of Hungarian estates elected Rákóczi their chief lord, thus avoiding the increasingly pressing question of the choice of the form of government. The other conflict in the region, the Great Northern War (1700–1721), was also decisive for the War of Independence. The Swedish king, successful in the first phase of the war, conquered a large part of Poland and defeated the Russian tsarist troops, but refused to support the kuruc, fearing the Habsburgs. The estrangement of the Swedish–Hungarian friendship prompted Rákóczi to contact Tsar Peter I. Nevertheless, the Russo–Hungarian alliance (1707) was of no real benefit, as the tsar only focused on defeating the Swedes.

The legendary military leaders of the kuruc, such as János ‘Vak’ (Blind) Bottyán or László Ocskay, were excellent in the raiding style of warfare. However, the armies, consisting mainly of cavalry, could not cope with the imperial troops retreating to fortresses. Besides, securing the funding for the war from 1707 was also becoming increasingly difficult. Neither the regular French aid, the income from the Rákóczi estates, nor even the regal revenues proved sufficient to maintain the army. The temporary copper money (libertas) issued for the War of Independence also lost its value over time. The Prince, having no other option, decided to take a bold step at that point: he planned to tax the nobility.

At the Diet of Ónod of 1707,

equitable taxation was enacted into law, and the dethronement of the Habsburg Dynasty, namely of Joseph I (r. 1705–1711) was proclaimed.

However, the kuruc armies started being defeated by the imperial (labanc) troops in open battles. The raiding tactics of the kuruc freedom fighters could not be used in those situations, and the poorly armed infantrymen (talpas troops in Hungarian) could not stand up to the volleys. The troops were supported by only a few cannons, and the aristocratic officers often failed to obey orders. Besides being outnumbered three to one, in 1708 these reasons also contributed to the

heavy defeat of the Prince’s troops at the Battle of Trencsén (Trenčín, Slovakia). The defeat marked a turning point: the unity of the kuruc camp was shattered.

Another blow to the freedom fight was that not much later the financially exhausted country was ravaged by the plague, which dismantled not only the kuruc camp but also the general staff. Tamás Esze, for example, was killed in a shootout among the kuruc, Vak Bottyán died of the plague, and Ocskay became a traitor. As the allied French were also forced to take defensive action, there was no hope of foreign help either.

The labanc were slowly pushing the kuruc troops back to the Upper Tisza region, whereas Prince Francis II Rákóczi, with nothing to lose and all to gain, desperately tried to save his movement: he travelled to visit Tsar Peter I, who was at that time fighting in Poland, and asked for Russian military help. But the commander-in-chief appointed in his absence, Sándor Károlyi, contacted the advancing imperial army, personally János Pálffy. During months of negotiations, Károlyi tried to obtain the most favourable surrender offer possible. He soon realized that the Habsburg Empire was also interested in a quick peace settlement as it wanted to avoid the Hungarian cause—especially the independence of the Principality of Transylvania—becoming part of the impending European peace settlement. This explains the significant concessions made by the Habsburgs.

The kuruc army, on the verge of total defeat, finally laid down the flag on the plain of Majtény in the spring of 1711, after concluding the Treaty of Szatmár (today’s Satu Mare, Romania), which marked the end of the struggle. The peace was accepted by Charles III (r. 1711–1740), who ascended the throne after the unexpected death of Joseph I.

The Treaty of Szatmár fulfilled some of Rákóczi’s minimal ambitions: for example, it proclaimed an amnesty for those who swore an oath to the Emperor, recognized the rights of the estates and the constitution, and promised religious freedom to Protestants, however, it did not restore the independent Principality of Transylvania.

Francis II Rákóczi was in Poland at the time of the Majtény surrender—but since he would never have sworn allegiance to the Emperor, he decided not to return to Hungary. He left first for England and then for France. Louis XIV had provided him with a secure livelihood, but after the death of the Sun King the French court became increasingly anxious to get rid of the Prince.

The war that broke out between the Ottoman Empire and the Habsburgs (1716–1718) gave the kuruc leader a final opportunity to return to his homeland, and after lengthy negotiations, Rákóczi travelled with his companions to Constantinople in the hope of a new alliance. However, by the time they arrived, the Turkish army had already been defeated, leaving the kuruc leadership stranded in Turkey. The Sultan soon allowed the emigrants to settle in Tekirdağ, where the final stage of the bitter kuruc exile began.

It was there that Francis II Rákóczi died in 1735; his ashes were brought back to Hungary, together with those of his mother Ilona Zrínyi and his stepfather Imre Thököly, to Kassa (today’s Košice, Slovakia) in 1906.

Read more on the kuruc and the labanc: