This article was published in Vol. 4 No. 2 of our print edition.

It is often argued that family and pro-family policies can offset the downward demographic trends in developed countries. I would like to challenge this notion by pointing out that it is often unclear what is now meant by ‘family’. Until recently, the traditional family structure included several generations, and was wider horizontally with many uncles and cousins being to varying levels part of the effective family. However, over recent centuries, this traditional family has been replaced across most of the world by the ‘nuclear’ family model, consisting of two parents with one to three children. In the last few decades, the nucleus has become even smaller, with many single-parent families and increasingly with only one or even no children. This trend, observable to one degree or another in almost all countries outside of sub-Saharan Africa, has brought about a dramatic shift in demographic trends, with below-replacement birth rates in most countries of the developed world, and even countries that are far from affluent, like India or Mexico, currently barely at replacement-level birth rates. In some countries, the downward birth-rate trend has already become catastrophic, with the population actually shrinking in some countries in East Asia and Eastern Europe, or only being replenished by substantial immigration, as in the case of Spain and Germany. Significantly, the trend for fewer or even no children is evident even in countries like Iran or China, who have catastrophically low birth rates, despite being regarded as having a ‘strong’ nuclear family structure, with low levels of divorce and few single mothers.1

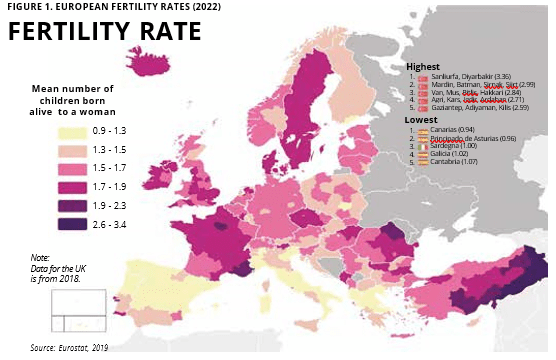

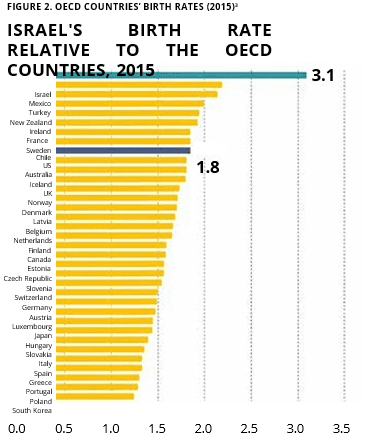

Obviously, this means that pro-family policies can have little effect on demographic trends if the ‘family’ unit has few or no children (Figure 1). It is then necessary to better understand what the term ‘family’ means in different places, and examine what cultural factors might mitigate or even offset the effective emptying of all meaning from the term ‘family’ in recent decades. One country which is eminently bucking the global downward demographic trend is Israel, and it might be worth examining some of the cultural aspects that characterize the Israeli circumstances, and learning some lessons from them (Figure 2).2

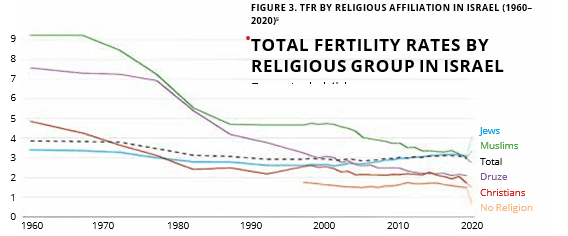

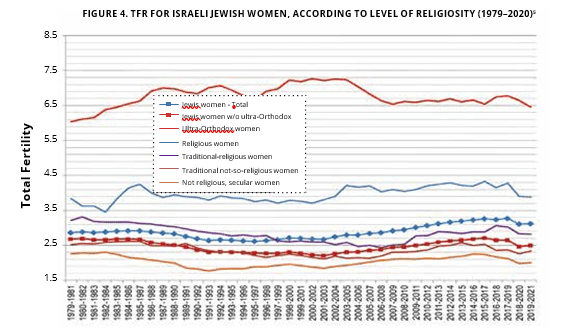

There is a widespread myth that Israel’s high fertility is due solely to the very high fertility of the ‘Haredi’ (ultra-Orthodox) sector in its society. This is not the case. Granted, Haredi birth rates are quite high, and they certainly contribute to the high overall birth rate, but Haredi birth rates have been stable or declining for two decades, and in any case this population consists of a relatively small segment of Israeli society (about 15 per cent), so they cannot be the cause of the Israeli birth rate remaining steady and even rising in recent decades. Moreover, the birth rate among the Israeli Arabs (about 20 per cent of the population) has also been steeply declining in the last two decades, so they too are not responsible for the demographic trends in Israel. It is in fact the mainstream Israeli Jewish population, ranging from religiously orthodox to so-called ‘secular’ Jews, that has had and continues to have an unusually high birth rate for a developed country4 (see Figure 3 and 4).

It is easy to see in Figure 4 that with small fluctuations, overall even the most ‘secular’, educated, and high-earning Jewish women in Israel have, on average, above-replacement level TFR of 2.1–2.2, while for Israeli Jewish women as a whole the TFR is above three children. Thus, the fertility of Israeli Jewish women is not only exceptional because it is high, it is also exceptional because the strong pronatalist norms it represents cuts across all Jewish educational classes and levels of religiosity. From an international perspective, these are highly unusual patterns.

If we look at the reasons for the difference in fertility between Israel and other developed countries, we see that they cannot be ascribed simply to the levels of education or employment among women, since Israel actually has, overall, a very high level of education and workforce participation among women (especially so among the ultra-Orthodox). Neither does the difference stem from the fact that in Israel relatively educated and affluent families are having more children than their counterparts elsewhere, because the difference in fertility between college-educated Israelis and their counterparts in, say, Europe, is much greater than the difference between non-educated Israelis and their Europeans counterparts. As a direct result of these fertility patterns, a higher percentage of children in Israel than in any other OECD country are born to older and more highly educated parents.6

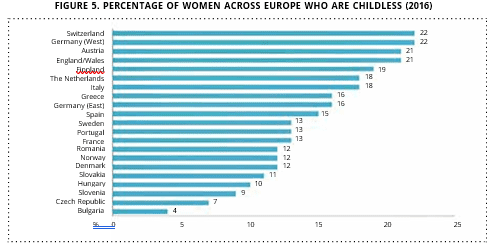

These trends are additionally supported by comparing data about the level of childlessness in different countries (Figure 5). The world leaders in childlessness among women tend to be economically and educationally advanced countries such as Japan (28 per cent), Singapore (23 per cent), Switzerland (22 per cent) and the US (19 per cent). The lowest rates of childlessness, meanwhile, are recorded in some of the poorest African countries, such as Congo, Angola, and Liberia, where contraceptives are out of reach for most, and childlessness is estimated at about 3 per cent (although reliable statistics are lacking). Across countries with high contraceptive availability, there is no direct relationship between prevalence of childlessness and TFR. Thus, some countries in Eastern Europe, like Hungary (9 per cent), the Czech Republic (7 per cent) and Bulgaria (4 per cent) have far lower level of childlessness than Western European countries with similar or lower TFR, like Germany (20 per cent), The Netherlands (18 per cent), or Spain (15 per cent). However, this apparent divergence might result from a distortion caused by the large numbers of women of childbearing age emigrating westward from Eastern European countries, especially in the case of Bulgaria, and thus only apparently lowering rates of childlessness in those societies.7

In Israel we find an unusual combination of a very high TFR with a relatively low level of childlessness. Israel has a 7.8 per cent childlessness rate among women aged 45–59. However, when this number is broken down, we find that among Arab women the percentage of childlessness is 13.7 per cent, the same level as affluent Western European countries like Sweden and France, while among Jewish women, the percentage is only 6.4 per cent, lower than in any European country save Bulgaria.8

Finally, we must consider that the high fertility in Israel might be a result of particular pro-natalist policies by the Israeli government. Nevertheless, unusual and generous policies towards government policies are not peculiar to Israel. For example, Israeli women work at almost the same rates as they do in, say, Canada, with 59 per cent workforce participation compared to 61 per cent in Canada, and they get far less time off when they have babies: three months paid maternity leave and another optional unpaid three months, compared to eighteen months of maternity leave in Canada.9

Thus, we must conclude that the real secret to Israel’s fertility rates is to be sought not in policies but in the national culture. Namely the centrality of the family. As for nuclear fertility treatments, funded by public money, it is the only country to fully subsidize unlimited in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatments for all women until they are 45 or have two children. The policy receives little criticism, despite the expense involved. However, this policy is of very little help in understanding the exceptional aspects of Jewish Israeli TFR, because we must remember that fertility treatments are equally available to all Israeli women, and thus cannot explain the divergence between Jewish and Arab women in Israel. For generations, economically advanced Western countries have increasingly put the individual at the centre of culture and society, seeing society as essentially a collection of individuals (also known as the Social Contract), leading to the undermining of even the nuclear family, as discussed in the opening of this article. Non-European societies like China and South Korea are also increasingly adopting this outlook, leading to a steep decline in the role of the family in society and culture.

Meanwhile, among Jews in Israel, the family is still very much at the centre of the culture and way of life. It might even be claimed that Israelis see their society more as a collection of families than as one of individuals—a nation as an extended family rather than a state as a social contract of individuals. A study of the sources for such a cultural outlook would justify a separate article. Here it suffices to say that the emphasis on family continuity is reinforced at every level of Jewish historical memory, from the preoccupation with family continuity being the main theme of the biblical stories of the patriarchs, through the family becoming the focus of Jewish communal life in exile when other national institutions could not survive, to the resolve after the Second World War to restore so much that had been destroyed in the Holocaust. On these significant Jewish foundations, the Israeli experience has, if anything, added additional layers of importance to the family, from the centrality of relying on your family when immigrating, for a nation where most of the population are immigrants or children of immigrants, to the family affirming the effects of living in a nation that for all of the 75 years since it was founded has been under external threat—exploding every few years into actual armed conflict. It is important to stress that in both traditional Jewish and Israeli culture, the idea of family is so crucially intertwined with continuity and childbearing that the latter takes precedence even over marriage.10

This centrality of continuity is so pronounced that even among religious Jewish Israeli women who have remained unmarried until their late thirties and early forties, there is a growing phenomenon of producing a child or two out of wedlock, by IVF, with the sanction of Rabbinic authorities and the active support, financial as well as practical, of their extended families. For all the very real preference and even sanctity of marriage in the Jewish religion, the sanctity of giving life and continuing the family legacy is regarded as even greater. Most importantly, in Israeli Jewish culture, children remain a blessing instead of the burden depicted in much of current Western individualist culture.11

The result has been that among Israeli Jews, getting married and having kids remains an essential part of one’s self-realization, thus making not individual but familial self-realization the highest cultural value. Moreover, for most in Israel, family is not the narrow ‘nuclear’ one of two parents and their children, but tends instead to be more a more extended affair, with the significant presence and participation of grandparents, often together with cousins and uncles, not only in once or twice yearly gatherings, but even in the day-to-day run of family life. Naturally, some of these practices can be found in many places, but what is exceptional in Israel is the extent of family involvement in what is a developed and mainly urban society.

‘The Israeli case is evidence that cultural aspects, rather than ‘‘family policies’’, are the crucial element in producing above-replacement birth rates among an educated and affluent population’

Significantly, the relatively small geographical area of the country, and the rejection of the nuclear family model in favour of the extended family, means that many Israelis choose to live in relative proximity to parents and siblings, with most of the population not more than a two- or three-hour trip by car from each other. As a result, we will find it quite common that Israeli grandparents or uncles pick up children after school, since many live in intentional proximity to each other, that cousins grow up together in the same neighbourhood, and that there is a high level of interaction with the extended family, not only on special festive occasions, but on a regular basis. Around the world, this way of life is probably still quite common in rural communities, but is increasingly rare in cities where most of the population lives, and where new generations are increasingly composed of those who grew up as only children and now remain single and unmarried. In Israel, the more traditional, extended family structure is still the dominant pattern even in the larger cities and the most affluent and educated parts of the population.

This way of life is strongly reflected around the country every Friday evening, even in the most affluent and secular areas: streets are deserted, and virtually all families gather around the Sabbath meal table of one kind or another, more often than not including grandparents, cousins, and guests. That trend is, of course, even more pronounced during the holidays, which in Jewish practice are centred around the family table, from the Passover Seder, to the sitting together in Huts at Sukkoth, to the lightning of the Hannukah candles for eight consecutive evenings and so on. Participation in some form of these practices is virtually universal, even among Jews regarded as ‘secular’—itself quite a problematic category when applied to Israeli Jewish practices and culture.

In conclusion, it appears to me that the Israeli case is evidence that cultural aspects, rather than ‘family policies’, are the crucial element in producing above-replacement birth rates among an educated and affluent population. It is therefore crucial, for those countries which regard such outcome as desirable, to invest efforts in fostering the cultural aspects of a familial outlook in their societies.

NOTES

1 For fertility rates in China (1.2 in 2021) and Iran (1.7 in 2021) see the World Bank website: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN?locations=CN; and https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN?locations=IR.

2 For Israel’s fertility rate (3.0 in 2021) see the World Bank website: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN?locations=IL.

3 Alex Weinreb et al., ‘Israel’s Exceptional Fertility’, in State of the Nation Report 2018 (Jerusalem: Taub Center for Social Policy Studies in Israel, December 2018), 5.

4 Weinreb et al., ‘Israel’s Exceptional Fertility’, 3–4, 10–13.

5 Lyman Stone, ‘A ‘‘New’’ Normal? An Updated Look at Fertility Trends across the Globe’, Institute for Family Studies (October 2019), https://ifstudies.org/blog/a-new-normal-an-updated-look-at-fertility-trends-across-the-globe.

6 Weinreb et al., ‘Israel’s Exceptional Fertility’, 22–26.

7 Weinreb et al., ‘Israel’s Exceptional Fertility’, 19–21.

8 Weinreb et al., ‘Israel’s Exceptional Fertility’, 19–23.

9 Danielle Kubes, ‘The Truth Behind Israel’s Curiously High Fertility Rate’, National Post (26 February 2023), https://nationalpost.com/opinion/danielle-kubes-the-truth-behind-israels-curiously-high-fertility-rate.

10 Ofir Haivry, ‘Israel’s Demographic Miracle’, Mosaic Magazine (7 May 2018), https://mosaicmagazine.com/essay/israel-zionism/2018/05/israels-demographic-miracle/.

11 Haivry, ‘Israel’s Demographic Miracle’.

Related articles: