The question of what kind of Christian culture the settling Hungarian tribes encountered in the Carpathian Basin around 900 AD is still a controversial one for researchers. The main area of interest here is the Transdanubian region, the classical Pannonia, where they may have found a fragmentary church organization with its associated communities, whose roots go back to Roman times.[1]

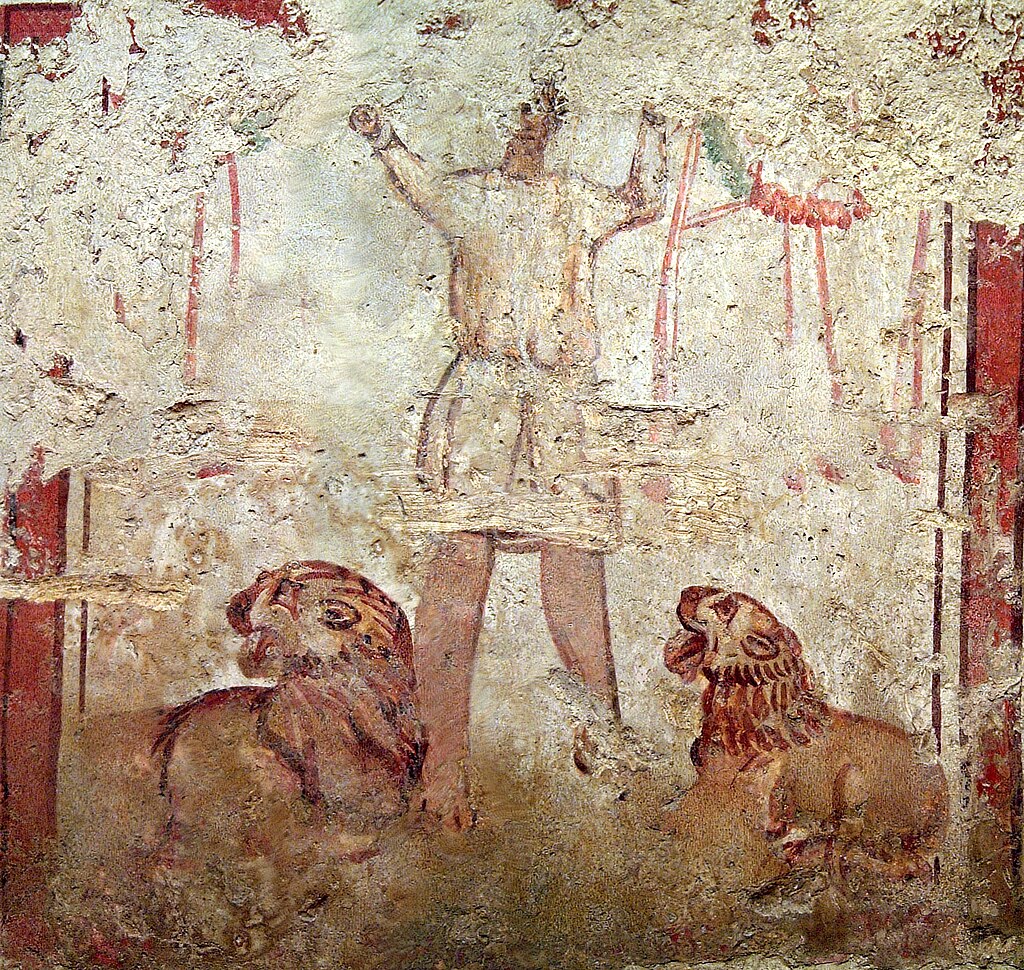

The Roman occupation of Pannonia took place gradually during the reign of Emperor Augustus (d. 14 AD) and in the following decades. The spread of the Christian faith here is first described in the sources on the persecution of Christians. The martyrs of Pannonia who appeared in the martyrdom records of the 3rd and 4th centuries were mostly clergymen, bishops, priests, and members of their families.

Pannonia was the most successfully Christianized area in the Carpathian Basin, alongside the Syrmian region.

Famous ecclesiastical figures were born here, such as St Jerome (b. ca. 342/347) in Stridon (located either in modern Croatia or Slovenia), St Martin of Tours (b. 316/317), St Martin of Braga (b. ca. 520), or suffered martyrdom here, such as St Quirinus (d. 309) in Savaria (today’s Szombathely, Hungary). St Victorinus, Bishop of Poetovio (today’s Ptuj, Slovenia), who suffered martyrdom in 304 and spoke both Greek and Latin, even preserved biblical commentaries.

After the Edict of Milan in 313, bishoprics were established in Pannonia by the end of the 4th century in Sirmium (formerly Szávaszentdemeter, today’s Sremska Mitrovica, Serbia), Cibalae (today’s Vinkovci, Croatia), Mursa (Eszék, today’s Osijek, Croatia), and Siscia (Sziszek, today’s Sisak, Croatia). The bishop of Sirmium, the former imperial seat, was considered the head of the Pannonian churches until the city was occupied by the Avars in 582. Later, the number of bishoprics continued to grow. In the 6th century, Scarbantia (today’s Sopron) most probably had a bishop, who was even mentioned as late as 572. The existence of a bishopric has also been suggested in Sopianaea (Pécs), Savaria (Szombathely), and Aquincum (Óbuda, part of Budapest), but it would be more difficult to confirm their existence in the latter places. After the abandonment of the border provinces, the Christian population may also have left, along with their priests and relics. This is how the body of St Severinus from Lower Austria was transferred to Naples, and that of St Quirinus from Savaria to Rome, first to the catacombs and then to the Basilica of Santa Maria in Trastevere.

At the same time, we can rightly count on Christian communities remaining and living on. The 4th-century relics of European importance in the area around Pécs are well known, which is the most important early Christian cemetery complex in Hungary. The hundreds of known tombs, burial chambers, and chapels are evidence of a large Christian community.[2]

Notable is the early phase of the so-called Keszthely archaeological culture, dating between 568 and 650. The Christian population that continued to live around Keszthely and the newly settled Christians left behind the three-nave early Christian Basilica of Fenékpuszta, with rich archaeological remains. Later, the Gothic people, the Gepids and the Lombards of the Great Hungarian Plain, who settled in the Carpathian Basin and to the southeast of it, were introduced to Arian Christianity. Their presence here is attested by a late 5th-century fragment of a Gothic translation of the Bible by Ulfilas (+383), used as an amulet.

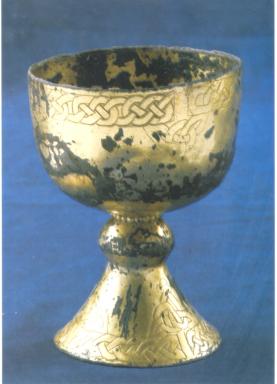

After the Lombards moved to Italy in 568, the Avars occupied the Transdanubian region. Most information from the late Avar period is available about the successful Frankish conquest of Transadanubia, which began with the great attack against the Avars in 791. This was followed in the early 800s by the rechristening of Avar princes to the biblical names of Theodore, Abraham, and Isaac, and in their wake a large number of Avar baptisms. According to the sources, we can reckon with the possibility of the survival of Christian ‘islands’ in the territories conquered by the Frankish armies. For example, the small 12 cm high chalice with the inscription ‘Cunpald fecit’ (meaning ‘made by Cundpald’) found in Petőháza in Sopron County, which is considered the most important Christian find of the 9th century, can certainly be linked to the Avar conversion.[3]

In connection with the 791 campaign, some sources and modern research assume that Charlemagne, out of respect for St Martin, stopped in Savaria, today’s Szombathely, on his way home. This would not be surprising, since Savaria, as the well-known birthplace of St Martin, was the best-known town in medieval Hungary in the Christian world. By 811 the Pannonian provinces were under direct Carolingian administration.[4] Organized into margravates with influence in the western Carpathian Basin, Carolingian and then Eastern Frankish states re-established orderly relations with Rome. The Frankish bishops were well aware of the coincidence between the boundaries of the empire and liturgical boundaries of the Church. The liturgy itself also had an empire-building, social-organizing, and acculturating role, as European political geography still attests in many places to this day.

Surprisingly, after 828, the Avars were no longer mentioned in the sources, but the Moravians entered the scene instead,

whose dominion extended to Pannonia and northern Hungary. This is linked to the conversion journey of St Constantine/Cyril and Methodius from Constantinople.[5] Their mission began with their arrival to the Slavic Comes (count) Kocel, who ruled Lower Pannonia from 861 to 876. This was followed in 863 and in 866–867 by their stay in Mosaburg (today’s Zalavár), not far from Lake Balaton. In 869, Kocel had already appealed to Pope Adrian II (r. 867–872) to send Methodius to him again and consecrate him bishop of Pannonia. Pope Adrian II gave written permission to the converts to use the Slavonic liturgy and to distribute biblical books translated into Slavonic. The Pope finally designated the ancient ecclesiastical centre of Sirmium as his seat, but Methodius did not occupy his, preferring to stay rather in Staré Město and Mikulčice (Czech Republic), but mostly in Mosaburg. It has been suggested that it was during Methodius’ stay in Mosaburg that the liturgical text translated into the ecclesiastical Slavonic language, known as the Kiev Missal after the place where it was held, was written, as well as other translations, now known as the Freising Manuscripts.[6] Other relics of their conversion remained as well, such as the gilded copper plates depicting the Ascension of Christ found in the defensive wall of the Moravian fortress of Nyitrabajna (today’s Bojná, Slovakia), which was still standing in the 890s.

By the 870s the building of the episcopal church organization reached a turning point.[7] The Pope consecrated Methodius as archbishop no later than the first quarter of 870, which, of course, was an affront to the interests of the Salzburg archbishops who controlled the Pannonian conversion. This explains why in 870 the Bavarian archpriests imprisoned Methodius and then condemned him by an ecclesiastical court at an imperial assembly. In 872 the Pope nevertheless reinstated Archbishop Methodius in his province of Pannonia and Moravia. However, strong Bavarian resistance prevented him from remaining in Pannonia and he moved his seat entirely to Moravia. As archbishop of Moravia, he was also given the bishopric of Nyitra (today’s Nitra, Slovakia), but it is disputed whether the church of Nyitra, which was re-established in the 11th century and became an episcopal see again in the early 12th, can be considered a direct successor to it.

The most important of the narrative sources on the conversion is arguably the work The Conversion of the Bavarians and the Carantanians, written in 870, perhaps by Archbishop Adalwin of Salzburg (r. 859–873) himself. This is one of the first written sources to give a coherent account of the history of later Hungary, in this case, the Transdanubian region. The work describes how the archbishops of Salzburg made great strides in building up the local church organization: a total of 31 churches were consecrated in 28 municipalities. This is a considerable number even if the consecration of the church in Nyitra was only included afterwards. However, the identification of these place names with modern place names is still a source of research problems and controversy to this day. One of the names that can be identified with certainty is Mosaburg (Zalavár), the most important church complex of imperial importance of 9th-century Pannonian Christianity. Three churches were consecrated here: the first was dedicated to the Virgin Mary, the second preserved the remains of St Adrian the Martyr, and the third was a baptistery dedicated to St John the Baptist. It is still debated to what extent the tradition of the church of St Adrian, consecrated here in the 9th century, influenced the foundation of the Benedictine monastery dedicated to St Adrian by King Stephen in 1019.

However, the church-organizing activities of the popes and the Bavarian churches remained only a torso—from the 880s onwards, thunderheads were forming over the revival of Pannonian Christianity. The Bavarian continuation of the Fulda Yearbook dramatically details the Frankish–Moravian struggles that shattered the tranquillity of Pannonia. The bloody fighting, even before the arrival of the Hungarians, caused irreparable damage to the settlement structure and ecclesiastical institutions of the region, which were thus left in a state of collapse when the Hungarian conquest came. As a result,

it took a good century for the new missions, with the birth of the Christian Kingdom of Hungary, to bring the region back into the Church once and for all.

András Alföldy, a professor at Princeton University at the end of his life, pathetically summed up the history of Pannonian Christianity in 1938, in keeping with the expectations of the times: ‘A whole series of warriors as solid as steel disappeared without a trace from the bottom of the Carpathians because they could not bow humbly before the glory of Christ. Though so cruelly destroyed, the Pannonian Romanism outlived them in spirit.’[8]

[1] István Zombori, Pál Cséfalvay, Maria Antoinetta De Angelis (eds.), A Thousand Years of Christianity in Hungary, Budapest, 2001.

[2] Dorotya Gáspár, Christianity in Roman Pannonia. An Evaluation of Early Christian Finds and Sites from Hungary, Oxford, 2002.

[3] István Bóna, ‘“Cunpald fecit”. Der Kelch von Petőháza und die Anfänge der bairisch–fränkischen Awarenmission in Pannonien’, Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, Vol. 18, 1966, pp. 279–323.

[4] Endre Tóth, Imre Takács, Tivadar Vida (eds.), Saint Martin and Pannonia: Christianity on the Frontiers of the Roman World: Exhibition Catalogue, Pannonhalma, 2016.

[5] Pavel Kouřil et al. (eds.), The Cyril and Methodius Mission and Europe — 1150 Years Since the Arrival of the Thessaloniki Brothers in Great Moravia, Brno, 2014.

[6] Florin Curta, Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages (500–1300), Vol. 1, Leiden–Boston, 2019, pp. 179–198.

[7] Béla Miklós Szőke, The Carolingian Age in the Carpathian Basin, Budapest, 2014.; Szőke, Die Karolingerzeit in Pannonien, Mainz, 2021, pp. 303–409.

[8] Jusztinián Serédi (ed.), Emlékkönyv Szent István király halálának kilencszázadik évfordulóján, Budapest, 1938, Vol. 1, p. 170.

Related articles: