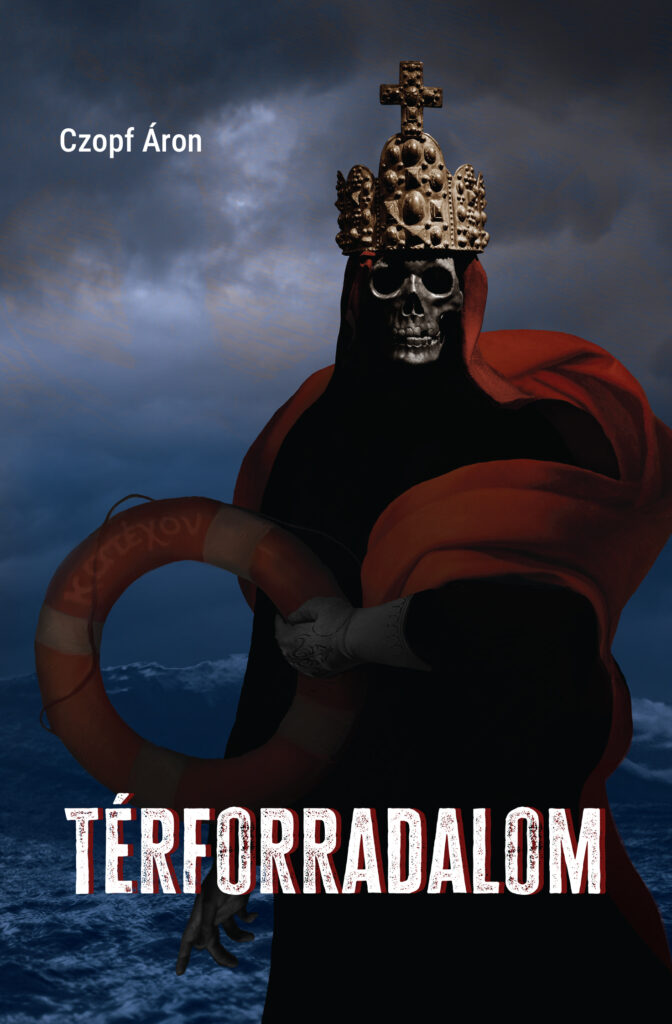

Áron Czopf’s book Térforradalom,[1] despite its brevity, contains such profound and important ideas that each small chapter could be reviewed separately. The book is characterized by terseness and a crystalline structure: the ideas formulated with mature elegance—sometimes quite maxim-like—could be thought about further in every case. The lack of ‘rhetoric’ here is refreshing; the further thinking is of course up to us, the reader, the recipient, the interpreter.

What is Térforradalom about? In short, it is about how ‘space turns into time’ in modernity.[2] Several philosophers have formulated this idea in some form, but the way it appears here is quite peculiar. The problem is not abstract in the least: we feel the general acceleration, in all areas of life, as a first-hand experience. Neither the philosopher, nor the football player or the local public servant can escape from it. But what does the idea of space and the idea of time mean in a deeper (not as ‘spacetime’ in physics) sense, and above all, what can be political (that is, revolutionary) in them? Based on the title Térforradalom, meaning ‘spatial revolution’ in Hungarian, we might even think that the revolutionization of space is some kind of progressive act. In colloquial parlance ‘revolution’ still means something positive; ‘revolutionary change’ or ‘revolutionary new idea’ means the ‘weeding out’ of something outdated, of a stagnant, ‘infested’ state, of something that calls for a necessary change.

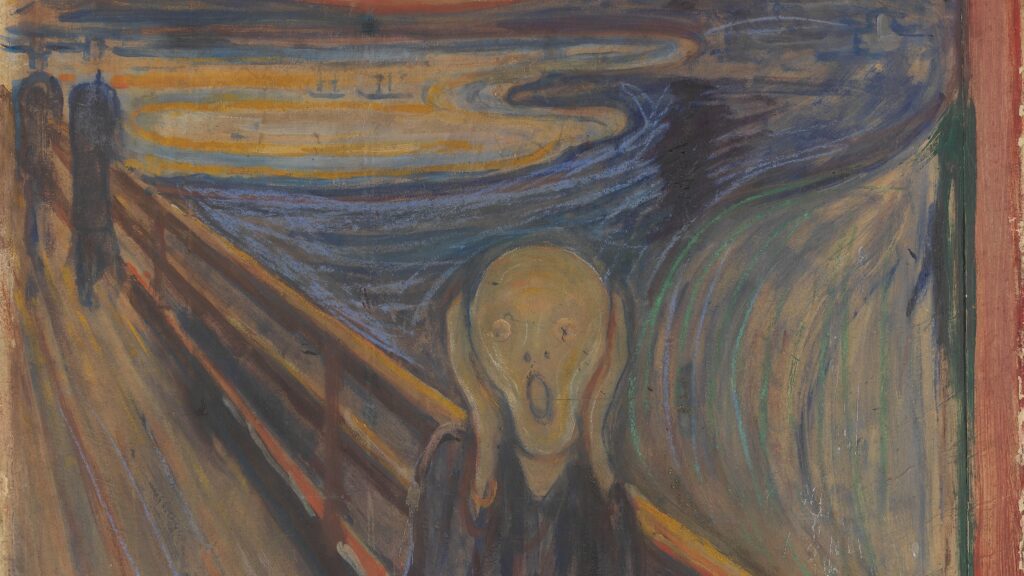

Now, in the ‘twilight of great illusions’ (Béla Hamvas), when even progressive elites prefer to talk about ‘sustainable development’ in the increasingly inextricable network of ecological, economic, biopolitical crises and war disaster narratives, the concepts of development and progress seem more and more imaginary, something that no serious thinker is interested in anymore. Apart from bombastic and at the same time profoundly misleading formulations such as the ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’ (Claus Schwab), even the word ‘revolution’ is starting to fall out of fashion. The revolution of space that Czopf writes about is actually a kind of counter-revolution—this becomes clear as soon as one starts reading the book. Something that is ‘not counter-revolution, but the opposite of revolution.’ (Joseph de Maistre.) A necessary reaction directed not at the creation of something (which does not yet exist), but at the recovery of something, the restoration of a lost state. Of course, considering the infinite number of states of existence, these two things can even coincide in the sense of coincidentia oppositorum, viewed from the time and space where we stand now; but we do not perceive it that way.

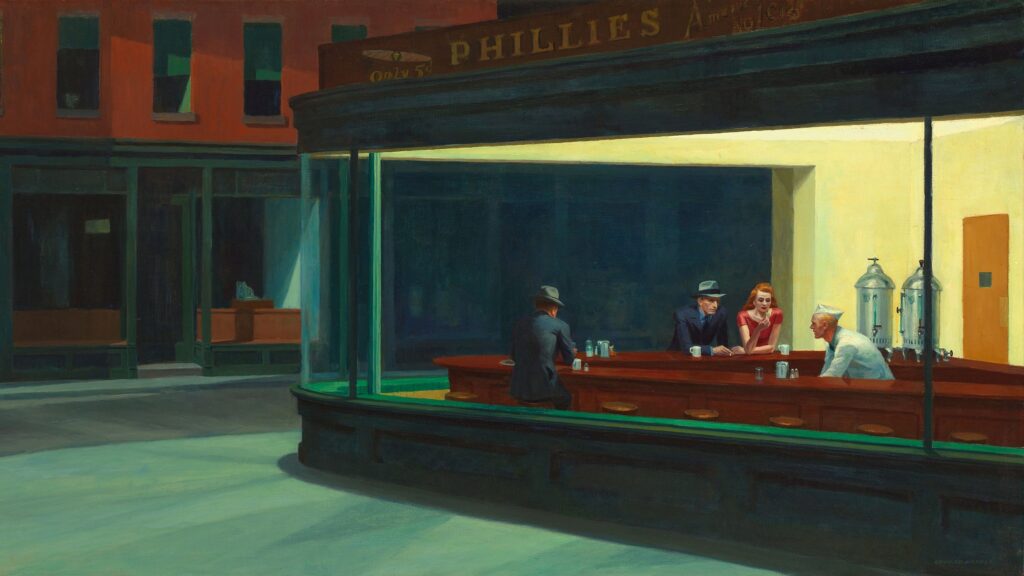

Our age is the age of ‘lack of time’—but instead we could say it as the age of ‘lack of space.’ What does that mean? It means that there is no place for anything in our world, but there is time for everything. Just like everything has a ‘price.’ One of the favourite slogans of progressive economism is ‘Time is money.’ However, space and time also represent the two archetypes of political existence (and all existence in general). Space inherently belongs to the polis, the starting point of political ‘residence’ (at least within the European cultural circle), and time belongs to the ship, the instrument of the ‘free movement of capital and labour’; the ship is an ancient invention but it is also—only developed later in time—a symbol of progression, change and technological dominance.[3]

According to the author, in traditional architecture, the house is the complete opposite of the ship.

The dwellings of the ancients were truly unique works of art, with a specific ‘personality’, usually with irregular contours and floor plans, often with their own names. However, from the 15th century onwards, the numbering of house gradually began to take over giving names to them. It’s as if man, ‘starting to build ships on land as well’, with functionality and the related regulations, and in the name of the principle of progress, first began to transform, then to cut up, parcel out, and finally, to destroy the traditional concept of space. According to one of the strongest statements in the volume:

‘Now let’s go to the airport, walk through a shopping centre, take a look at our public buildings. Modern architecture also builds ships on land. Between the panel houses and office buildings, people avoid each other as dispassionately as if they were temporary companions on an ocean liner. No one has anything to do with anyone. Yes, as if nothing bound them apart from the payment of travel expenses: they tolerate each other’s company during the day, and then everyone retreats to their cabins in the evening.’

A direct consequence of the ‘time revolution’ of modernity is that ‘we have mechanized the human milieu. Otherwise, we would sink.’[4] Revolutionized time essentially indicates the rejection of the fundamental spatiality of existence. By bringing the Earth under technical control, distance ceases, space shrinks, becomes insignificant, and finally disappears. It took Columbus three months to sail to America; today, the flight distance between London and New York is less than ten hours. However, we have paid the price of comfort and speed much more heavily than the techno-optimists thought: and we should not just think of the carpet bombing of Dresden or the atomic bombs dropped on Japan here. Modern total war is horrible, but it is an ‘occasional’ thing. However, with the invention of the clock, we lost one dimension of our existence and became invisibly slaves to time. Traditional man did not know the clock; the modern concept of time did not even exist for him. Most people didn’t even know exactly how old they were, and it really didn’t matter. In comparison, modernity already ‘nationalizes time’: ‘invoking the modern requirements of military logistics, makes laws that destroy the prerogatives of space.’[5]

The Field Marshal von Moltke, one of the greatest Prussian military strategists of the 19th century and the hero of the Franco-Prussian War, was the first to propose the introduction of the imperial ‘uniform time’ so that military troop movements could be better coordinated. Ever since the imperial uniform time was introduced and philosophers ‘embarked’ on that ship,[6] modern man has made several attempts to ‘realize heaven on earth.’[7] Today we can see with what results.

Time mostly meant a kind of deep, cosmic rhythm for the traditional man, with each day and month having a specific quality and a sacred meaning. The whole existence of man was smoothed into the universal breath of the great cosmic order. The wise man, that is, the person researching the secrets of existence, did not want to ‘progress’ but to ‘arrive.’ One of the greatest symbols of medieval Christian civilization is the Gothic cathedral, a good example of this spatial order.

‘Revolutionized time essentially indicates the rejection of the fundamental spatiality of existence’

‘This is the logic of the cathedral: a demand for order that is not the result of mere human reasoning but emerges from the natural order of things. The building stones would be interchangeable if they were qualitatively identical, but anyone who examines the structure of these churches can see for themselves that the larger structural connections cannot be freely transformed at all. The unity and proportions of the order that the cathedral displays are not an aesthetic luxury, but the only solution by which collapse can be avoided.’[8]

Traditional man was part of the cosmos (that is, the ‘good order, orderly arrangement’). At the same time, he is the image of God, he has an immortal spiritual soul, he is also its ‘shepherd’ (according to Heidegger’s comment: ‘man is the shepherd of Being.’) Medieval peasants woke up when the sun rose and went to bed when it set. The long winters (at least in the northern part of Europe) were not opportunities for work, but for the development of social space, after the autumn harvest, the activity stopped. In such cases, there was space and time left for people to pay attention to each other. Since there was no blare of the global media suppressing all other voices, there was no channelling of opinions, and there was no manipulated control of thoughts through mediatized communication—carried out through technical rationality—the opportunity for people to really talk to each other was created. Since they were not always ‘in the know’ of everything almost immediately, the overabundance of information was simply not available. Human communities could develop an authentic culture in which nothing was instant and globalized. Folk dance, folk music, folk textiles and folk architecture everywhere showed a topocentric character typical of archaic (that is, ‘close to the origin’) spaces, which once existed all over the world and—in contrast to the uniformity of the globalized world—yet it had everywhere an individual face.

In winter, people did not work, but usually celebrated something. In the Western Christian world, for example, the ‘Christmas holiday circle’ (the period from the first Sunday of Advent to Epiphany) were part of this period which, instead of agricultural work, mainly done in summer and autumn, was a time for everyone to turn inward and experience the sacred. Modern man ‘relaxes’ (like a machine) during the Christmas break and rushes to ‘recharge’. The expressions are revealing.

The revolutionizing of time was brought about by the all-pervading idea of efficiency. From the 18th century onward, ‘progress’ was mostly measured in this. No one should miss out! From the 19th century, everything started to ‘catch up.’ No one wanted to finish last in the eternal ‘race.’ And the ‘competition space’—that is, the time-order most closely related to acceleration—became the basic fact of existence.

‘Getting on the ship metaphorically means the development of modern political thought, the departure from the polis based on solid land structures and the beginning of a long journey in the liquid, boundless horizons of time.’[9]

‘Modernity is itself totalitarian. It’s like a huge, all-consuming mouth’

To submit everything to competition: this was one of the most important aspirations of the 19th century time-regimes. While the supporters of ‘free competition’ expected that the most valuable elements would be selected, in reality the opposite happened: the most worthless became the most popular, and in connection with the production constraint (the ‘ideology of growth’), the so-called mass needs, i.e. the needs of the least sophisticated people, came more and more to the fore—satisfying these needs being the ‘most profitable.’ The appearance of the so-called ‘mass culture’ can be dated from here, which, in contrast to the popular culture in spatial regimes, is poor and everywhere in the World showing the same uniformity.

According to Czopf, modernity is itself totalitarian. It’s like a huge, all-consuming mouth. What is important is not the guise of this totalitarianism. Liberalism can be totalitarian just like communism or fascism. All modern regimes are time-regimes, or more precisely: ‘Hegelian time regimes’[10]—being for him, one of the most important philosophers of modernity—along with Nietzsche—Hegel. Of course, conservatives have also previously viewed the philosophy of the ‘World Spirit’ with deep suspicion. The ‘self-movement of the World Spirit’ represents a teleological principle that is at odds with their experience of the world, which is nothing but ‘cathedral logic.’

‘In conservative thought, the idea of spatial order rears its head both here and there…the cathedral represents the protracted work of generations, it transforms time into spatial form, thus forming the perfect opposite of the principle of progress.[11]

However, the ground seemed to have finally slipped from under the feet of traditional conservatives when, in the 19th century, the logic of the cathedral was replaced by the logic of the ‘linear city’[12] by progression.

‘Whoever stops, holds up the line,’ and from a certain moment in history, it seemed that no one wanted to stop or ‘look back.’ Modern conservatives have become ‘cautious’ representatives of the ideologies of progress with different hues, or they have simply ceased to be factors—at least for the political life that has an effective influence. What was the result? Today we can clearly see it, especially in the western part of Europe.

In the twentieth century, there were not only two unprecedented (total) wars, but the totalization of the entire world. Space has pretty much disappeared, but at the same time, there can be no freedom without space. The public square, that is, the forum, is the most authentic form of existence of the Zoon Politikon. Instead of the forum, the most typical symbol of the twentieth (and twenty-first) century is what the author calls the linear city. Modernity is a kind of ‘queuing logic.’

‘We need to pay, then we should leave as soon as possible. That’s why deafening music plays in restaurants: to make people eat faster, talk less, and thus give up their temporarily occupied seats to others first. This is how our city turns into a timeline through the acceleration of consumption…Whoever stops holds up the line.’[13]

It is no coincidence that the national freedom struggle against communist oppression also started from Bem Square in 1956, writes the author.[14] ‘We stand with each other and with the space—we are already defenceless against the arbitrariness of foreign powers.’[15]

So here we stand now. What can be the task of conservatives in progressive time regimes? Does anyone even consider the voices that emphasize the rights of space over the rights of time? If we don’t want to be complete ‘slaves of time’ and sink along with the ship that has obviously developed a leak, the author suggests we should pay attention to these voices ‘the voice on one crying in the wilderness’.

‘Space plays the same role in politics as silence does in music: we always find it in the background, because it not only precedes politics, like the silence of the moment before the conductor’s first gesture and the starting note, but it also determines its internal structure.’[16]

All this is not just abstract reasoning against the all-powerful tyranny of ‘Hegelian time regimes.’ Reclaiming space is, above all, a political task, a step that can be carried out by those who are able to revive within themselves ‘the sacred and political principles of spatial organization’ and who have not yet been completely dominated by ‘logistical apathy.’[17]

All in all, the book is like a breath of fresh air, and therein lies its (counter)-revolutionary potential already evoked in the title—a refreshing wind over a region of bad smells. Instead of ‘spatial revolution’, the title could also be ‘the counter-revolution of Space’. The book itself could be compared to a heavy stone thrown into the stagnant water of a bog: of course, we will only be able to measure the size of the ripples it causes later.

[1] Áron Czopf, Térforradalom. Budapest, Századvég, 2014.

[2] Czopf, Térforradalom, 127.

[3] Czopf, Térforradalom, 83.

[4] Czopf, Térforradalom, 85.

[5] Czopf, Térforradalom, 61.

[6] Czopf, Térforradalom, 65.

[7] Czopf, Térforradalom, 68.

[8] Czopf, Térforradalom, 37.

[9] Czopf, Térforradalom, 92.

[10] Czopf, Térforradalom, 125.

[11] Czopf, Térforradalom, 35-36.

[12] Czopf, Térforradalom, 129.

[13] Czopf, Térforradalom, 129.

[14] Czopf, Térforradalom, 32.

[15] Czopf, Térforradalom, 33.

[16] Czopf, Térforradalom, 30.

[17] Czopf, Térforradalom, 44.