This interview was originally published in Hungarian on Mandiner.hu.

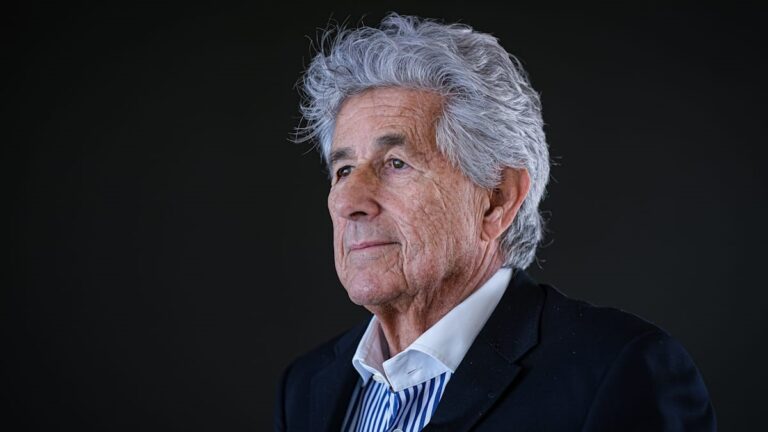

James Carafano is a leading expert in national security and foreign policy challenges, an accomplished historian and teacher, as well as a prolific writer and researcher. He currently serves as Senior Counselor to the President and E.W. Richardson Fellow at The Heritage Foundation. He is a graduate of the US Military Academy at West Point and served 25 years in the US Army, retiring as a Lt Colonel. He served in Europe, Korea and the United States. He also holds a master’s degree and a doctorate from Georgetown University. He granted an interview to Mandiner while in Budapest at the Fourth Danube–Heritage Geopolitical Summit in September.

***

If we talk about Hungary, it’s a relatively small country, you know, we are a landlocked country. There are only maybe 15 million Hungarian people all over the world, and we have really unique names.

I didn’t say that! (laughs)

But Hungary has become really important in American politics in the last ten years or so. Donald Trump talks a lot about our Prime Minister. American NGOs, like the Heritage Foundation, have really started networking with Hungarian institutions in the last couple of years. Why do you think that is the case?

Much like Donald Trump really didn’t create the modern conservative movement in America, most conservatives have migrated to the Republican Party, so the Republican Party has essentially become a conservative party. What distinguished Donald Trump was that he recognized and addressed that. So Viktor Orbán didn’t create European conservatism, but two things happened at the same time. One was when we saw this kind of surge of populism in Europe ten years ago, which is kind of a threat to the left, and the hammerlock that elites had on all the institutions: education, the European Union, Brussels, everything. The idea was to kind of step on that, right? And both Hungary and Poland were kind of the poster child of that. The elite thought, ‘We’ll crush these upstarts and that would be a lesson to everybody else.’ But the reality is, if you look at that, conservatism is probably the fastest growing and most influential political movement in the world today.

If you include everybody from the centre-right to the right, in the United States, it’s at least half the country, 50 per cent of 330 million people. In Europe, if you add up everybody on the right, it’s actually the dominant political voice. It’s just that they don’t all get together, so you don’t see that. But it’s also true in Latin America, where you have a conservative government in Argentina. You’re going to have one in Chile, Paraguay, and Uruguay. So there’s actually large conservative populations in Brazil and Colombia. Other countries, like Guatemala, they’ll all flip back someday. And even in Africa, you see a lot of governments would share common views on social issues, economic growth, and the push-back against the Green New Deal. So it actually is a growing movement.

‘Conservatism is probably the fastest growing and most influential political movement in the world today’

And so I think two things have kind of put Hungary on the map of the United States. One is, which is when Hungary was kind of under this direct assault, that bridge to the United States was to really break out of political isolation, to fight back on the demonization. And we actually saw the fruits of that really when Meloni was elected in Italy. Because when she was elected in Italy, the first thing that the EU did was to say that she was a fascist. And the first thing the news in America did was to say that she was a fascist. And what did conservatives in America do? They said, wait, wait, time out. We know this woman. She’s not a fascist. In many ways, that was a product of the lesson learned from the Hungarian experience, because as American conservatives get to know more European conservatives, they understand that we don’t agree on everything, but that what pulls us together is more important than what divides us. And then the other thing is that Hungary has made a very serious effort to broaden that dialogue among the global conservative movement. I’ve been in this business for a quarter of a century. The first time I was ever in Delhi there was an Indian conservative; an American conservative, which was me; and a European conservative on a dais together talking about conservatism in India; I’ve never seen that happen before. So I think that whether it’s in Latin America, in Africa, across Europe, I mean, Hungary is really a connector connecting conservatives together.

I think this is to prevent the political isolation of Hungary, which is wrong. But the other thing is, it is because it’s a growing global movement and Hungary’s actually helping that movement connect.

And how can we connect? Is it through NGOs and networking that it can become a reality?

Yeah, so again, two things. Look, one is, of course, the global left is really good at this. We all know about George Soros and the Open Society Foundation, they connected with billions of dollars. Matter of fact, if you look today at the antisemitism rioting and protesting in the US, this is not organic. These are not kids. This is basically paying these networks to put together political infrastructure to put people on the street.

We don’t have that kind of money. And actually, I think money is an evil. It’s easy to get people to work together when you’re basically paying them. The networking among conservatives is largely organic. It’s about collaboration and consensus building, not driving orthodoxy. The left’s approach is, you believe what we believe. But conservatives are an unruly lot, right? We don’t all agree on everything. Even across Europe, for example, what a centre-right party may think in one country is different than in another country. The whole purpose of conservatism is not to drive to a particular orthodoxy. And we don’t conserve things that are old. We conserve things that work.

‘The networking among conservatives is largely organic’

The differences in the dialogue and the debate are about how you get to deciding what are the best ideas, and the best ideas for you, not the best ideas for everybody everywhere. What are the best ideas for my people in Hungary, for my people in the United States, or in Argentina. So I think it’s about coming in with an attitude of collaboration and dialogue rather than driving at a particular orthodoxy like Soros is doing.

The second thing is, it’s about issues, not narrative. The reason why people turn to conservatives in the end is because the problems aren’t being solved. So you have to put policies and issues on the table that address what people care about. And not only that, it’s not just about winning elections and taking power, it’s about actually governing. I think Hungary is a good example of this. Look, this is a government that has won elections because it has listened to the people and what they want, and it’s tried to deliver on that. You can argue it’s not perfect. You can argue they don’t have all the answers. But you can’t argue that they aren’t focused on delivering on the issues that people care about and that they’re not delivering. So it’s about clarifying where you are on issues and about developing that capacity to govern. And then the third thing is, and this is the one thing that’s true all over the world, which is the instruments of civil society, of international engagement, even if they’re dominated by the left, in part because people like Soros have dumped enormous amounts of money in this thing. But also in part because these elites are embedded in basically holding onto political power. And you have to create alternative instruments to reach people, voters, your population, whether it is social media, public media, think tanks, or government organizations. Conservatives are successful where they do that. And networking is a big part of that.

Most people think of networking as socializing. That doesn’t necessarily mean anything. Yeah, it’s great to have a lot of followers and all that, but it’s when virtual networks connect with real people on the ground that real action happens. You have to be there, which is why I think the physical presence of Hungarian voices in places makes a big difference. So does the bringing of diverse voices here. I’ve been coming to Hungary for a long time, I’ve dealt with many forums. And the thing that’s interesting to me is they don’t always bring over people that agree with them. I think that’s great. So, there is a diversity of voices that are brought here. I brought a delegation to a conference we’re participating in with the Danube Institute. It has a diversity of voices from other US experiences, and I think that’s what’s making a difference.

You have mentioned issues. So what do you think are the most pressing issues of today? Is it immigration, is it child protection, defending conservative values, or something else?

As I go around the world and talk to different people in different places, obviously, people have different answers. I do think that there are some answers that do connect us all. I think immigration and border security is one because, among the many challenges it creates, it’s a fundamental threat to national sovereignty. And many people that have experienced illegal immigration on a large scale see the same kinds of problems, whether it’s contributing to transnational crime, undermining the rule of law, huge fiscal burdens, disruptive impact on the society, or creating potential for terrorism. And so that’s a common issue.

Energy’s another one. Green transition is a threat to all of us. First of all, it’s not actually going to address climate change. And second of all, it is going to hamstring developed countries and destroy growth. It is going to keep developing countries in energy poverty. The alternative is a belief in delivering reliable, affordable, dependable energy, that’s a key to growth. And then countries will have more assets and resources to mitigate and address whatever issues they want to address regarding climate change and the environment. I think that’s a common bond that I see everywhere from the centre-right all the way over.

‘Conservatives aren’t really interested in dividing the world into ours and theirs’

Cultural issues are part of this global discussion. Now, it’s different in different places, but education, life, family, these are all on the table because the alternative vision is basically destructive to all of these. Now, you don’t 100 per cent have to agree, for example, on what the right policy on education is or what family policy should be, or how you feel about life issues and what you think the right answer is or other health issues. But you know the wrong answer. This is super interesting for me as a guy who’s grown up working in the National Security and foreign policy. The issues of the day were how to deal with Iran, China and Russia; the issues of the day now are how to unite on energy, border security, family issues. Look, conservatives aren’t really interested in dividing the world into ours and theirs.

People recognize the reality that largely China, Russia, and Iran are disruptive in dangerous substances. Not everybody has the same stake in that fight, we get that. But what does the rest of the world do? You’re not going to divide into a blue and a red camp. Nobody wants to fight ‘forever wars’. Nobody wants to do regime change. Nobody wants to do nation building. And I think the one thing globally that you can find in common with conservatives is that they are friends and allies that believe in free and open spaces and want to develop their economies, and that there’s a desire to connect; whether it’s the three C’s initiative or the middle corridor or connecting through the Middle East to the southern corridor to India, Japan, and Korea; or connecting across the Atlantic to the economies in Latin America or across the Mediterranean to North Africa, East Africa. This is something I think generally I find to be of great interest to conservatives around America.

The issues of education and immigration are kind of left-wing issues.

That is what they claim, right?

Yes, at least that is what they claim, that these are the issues of the left. They are in the universities, they are in power in many countries, and they say that the only good answers to these issues are what they say.

But that is what I think the big difference is, that they have an orthodoxy. They say, we have the answers, and your answers are wrong. I mean, this is the reason why conservatives are involved in this, because we see their answers as just wrong. We may not all agree on what the right answer is, but we know you have a wrong answer.

Another issue which I see increasingly common among conservatives wherever I go is combating antisemitism and anti-Zionism. Everybody recognizes what it is, which is fundamentally a poison and a threat, whether it’s on the religious front or a foreign policy in the Middle East, or political stability. It’s a gateway for Islamists. Ten years ago I’d go to conservative events, and nobody was talking about anti-Zionism or anti-Semitism. And that’s because I think we all were generally like, ‘Well, who would be for this, right?’ So we didn’t have to talk about this stuff. And now, literally, the global left has adopted the causes of anti-Zionism and antisemitism. It has, I think, mobilized conservatives to push back against them.

Read more interviews from the 4th Geopol Summit in Budapest: