At the outset, I would like to say a few words about what I call traditional conservatism or the traditional New Right. In this regard, it seems appropriate to highlight some facts that are becoming more and more blurred nowadays. One form of conservatism, for example, has now taken power in Latin America, in Argentina. Mr Milei and his PR staff offer a kind of syncretism between conservative tendencies in understanding the world and liberal practices both in politics and, above all, in the economy. On the other hand, we also encountered similar tendencies at the NatCon conference in Brussels this spring. This movement can quite rightly be called the New Right/nueva derecha, which is also the term used by one of its main theorists, Agustín Laje.

I myself am convinced that we need a New Right and that the New Right must accept its location in a socio-economic and socio-political world that was not created by conservatism, quite the opposite: it is the extreme consequence of the movement that launched conservatism as a reaction to itself. And yet I also think that we should be a bit more ‘conservative’ in our conservatism. It should be emphasized here that we need new syntheses more than syncretisms. A fruitful synthesis, however, is possible only when the core elements of the individual entities that merge are discussed, since syncretism is always the result of the union of the apparent compatibility of surface phenomena, without taking into account the incompatibilities of the cores from which they originate. In a word: conservatism must seek a synthesis or at least a dialogue with non-conservative elements (which now dominate the world), but at the same time keep its cores intact. It is therefore necessary to define what they are.

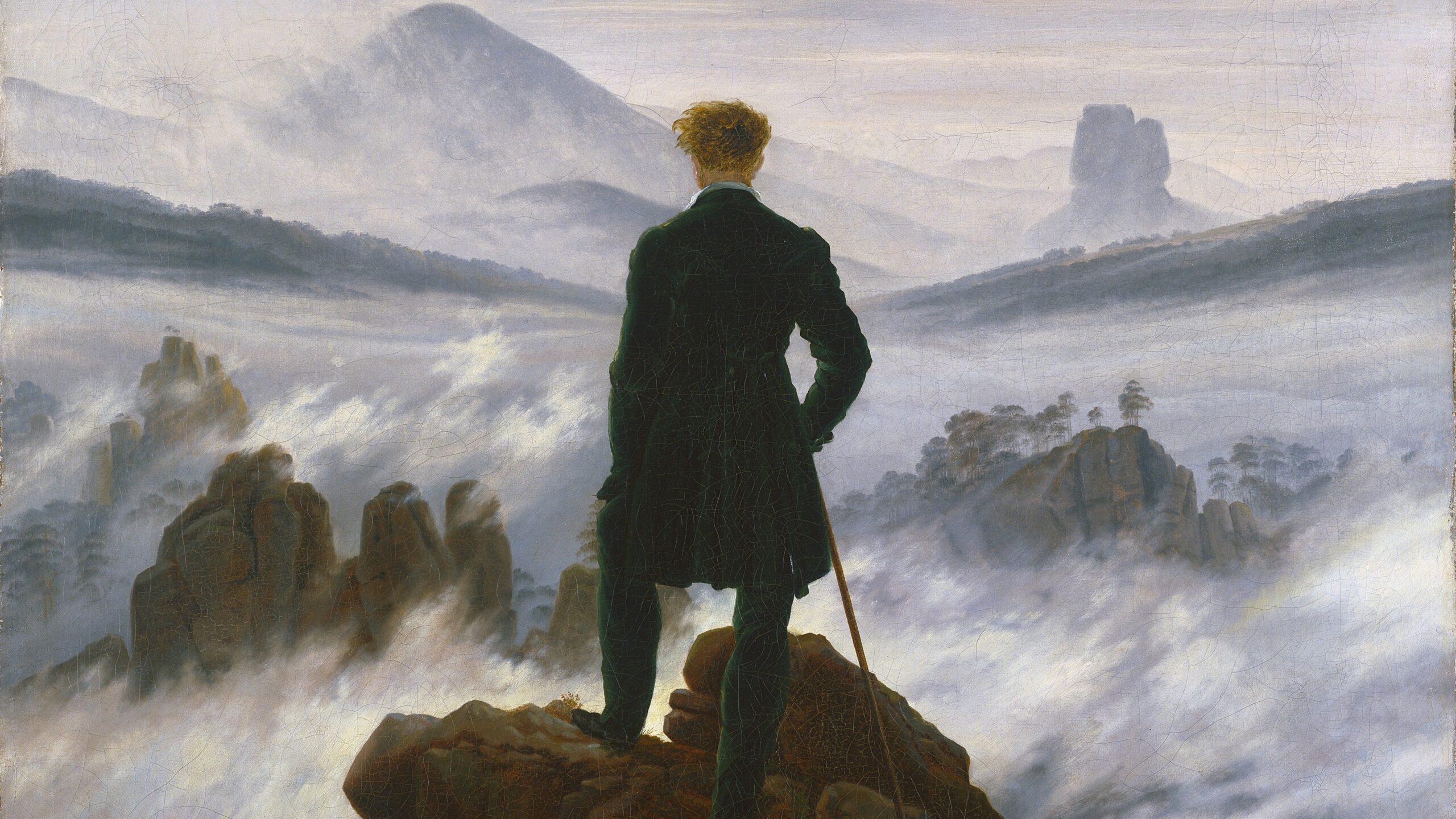

Regardless of the individual areas of its application, where it is possible to trace the essential conceptual units from which the conservative theory emerges, I believe that the true ontological essence of conservatism is contained in the definition: conservatism is the making present of actuality. In this way, conservatism is bound both to the particularities of specific belonging cultures and to the wider belonging civilization. Both culture and civilization contain something that always addresses them and from which they always speak, regardless of time or space limitations. Conservatism as a political philosophy arises when the address of the aforementioned actuality is threatened. When actuality is unmistakably present, there is no need for conservatism. Its task becomes necessary when actuality is obscured and it is necessary to retrace it and create the conditions for it to speak again. This could be called the ontology of conservatism. This is also the task of the new conservatism or the New Right, as it is basically emerging everywhere in the world. It is a phenomenon that changes the sign of conservatism and transforms it from a reactionary force into a positive creative force. The New Right, such as we encounter it in the theorists of the Argentine government and in movements such as NatCon, with its criticism of the modern world, which is such that we conservatives completely agree with it, must take another step towards defining its ontological essence, because only this can enable it to have a synthetic relationship to the modern world.

Differences with Respect to Liberalism

The importance of the ontology of conservatism in all clarity shows itself in its relation to liberalism. I myself note that there is considerable confusion among the New Right regarding this phenomenon. This is particularly true of the relationship between conservatism and liberalism. In this, the English thinkers are leading the way, in my opinion, for two reasons: because they try to build on the non-revolutionary tradition of liberal philosophy; and because they associate the greatest achievement of their conservatism, the common law, with Hayek. Confusion arises especially when concepts as freedom, rule of law, market economy, etc are used. In this case too, it is necessary to go to the roots, namely to anthropology. The conservative understanding of man is diametrically opposed to the liberal one: conservatism understands man as a zoon politikon, liberalism as an optional individuality that freely establishes one or another relationship with its surroundings. This fundamental difference manifests itself in all areas, including the understanding of individual freedom, which is supposed to be the greatest achievement of liberalism and which, with the political systems that liberalism builds on the basis of this concept, mostly attracts the contemporary New Right (and also the New Left).

‘The conservative understanding of man is diametrically opposed to the liberal one’

In reality, the concept of freedom, as soon as we implement it from the aforementioned opposing anthropologies, turns out to be completely different and incompatible. Emblematic of this is the work of a broad-minded liberal, Isaiah Berlin, entitled ‘Two Concepts of Liberty’. Conservative anthropology understands man as a completely religious being (more on this below) and therefore cannot agree to an understanding of freedom that includes only two types. The same applies to almost all areas occupied by liberalism in modern reality, including and especially regarding the issue of the economy, where it seems that all surviving worldviews must adopt a liberal model. We must be absolutely clear about this. Conservatism defends the inviolability of private property, which it understands even existentially, and defends the market economy, primarily as a competitive exchange of goods, but rejects the idea of the self-regulation of the free market, because all this is not in accordance with its anthropology. Conservatism is also not a supporter of capitalism, but it does not understand capital as the source of all evil, which is true of socialism. Conservatism advocates a market economy regulated by entities that form an organic society, of which the state is the highest ideal achievement.

In the context of the aforementioned New Right, tendencies that even try to unify conservatism and so-called ‘classical liberalism’, saying that they have the same or at least similar origins, and above all, similar views on many social phenomena, are appearing more and more clearly. I myself believe that this is only an appearance and that such attitudes sooner or later lead to confusion and serious disagreements, or at least to contradictions. However we look at it, this question is extremely important, because we all, liberals and illiberals, live in a world created by liberalism. Therefore, instead of wasting its energy trying to establish a dialogue with liberalism, the New Right should try to assert its views within a liberal framework, and before that, of course, go to its own roots. That is to say that it should establish a selective attitude towards the liberal framework in which we live.

Differences with Respect to Socialism

Even with regard to the relationship between conservatism and socialism, it is necessary to look at individual anthropologies. The differences between conservatism and socialism are arguably more obvious than those between conservatism and liberalism. Moreover, conservatism and socialism, especially in an age of culture wars like ours, are in near-permanent conflict, so the differences are more pronounced. However, anthropologically speaking, conservatism and socialism are somewhat more alike than conservatism and liberalism, since both understand man as a zoon politikon. In any case, their differences in many regards are profound. For instance: what does politics mean, what does community mean, what is sociogenesis, etc? The differences are of course too numerous to cover here.

Above all, there is almost no desire to create a synthesis between conservatism and socialism in the contemporary New Right. We conservatives see socialism as a completely failed experiment with no future. This has not always been the case in the past, and this has created perhaps the greatest humanitarian tragedy in human history. And yet there is an area in which conservatism not only meets, but more or less openly clashes with socialism: these are the already mentioned culture wars, where it is primarily a question of values. In this regard, the New Right must confront not only the results, but also the content of the cultural wars it is fighting with socialism in as much detail and quality as possible. All forms of progressivism, ranging from neo-Marxism to wokeism and liberation theology, etc, must be understood as forms of socialism. If it wants to be politically successful, that is to say: to offer an alternative to the prevailing system in the modern world, which consists of various combinations of progressivism and liberalism (we could call it libertarianism), the New Right must create its own counterculture, and this presupposes first a conflict, and then a victory in the culture war, for two reasons: because the condition for the creation of a conservative counterculture is the creation of a spiritual space within the space in which progressivism/liberalism currently rules; and because the purpose of the counterculture is to create a social atmosphere and mood that will enable the establishment of conservative ideas on a ‘common sense’ level.

‘We conservatives see socialism as a completely failed experiment with no future’

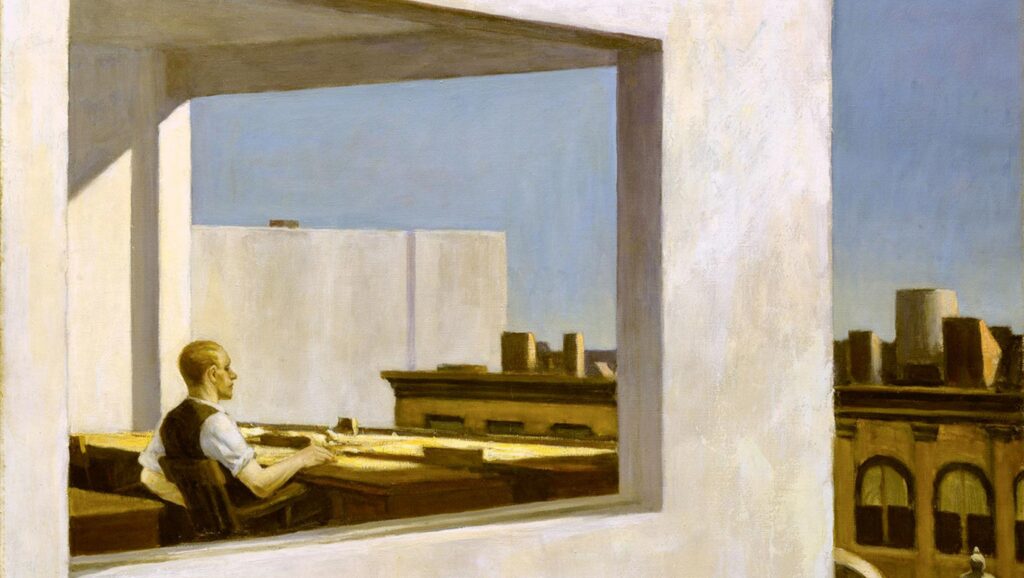

This whole process, of course, presupposes first a confrontation, then an attempt to create a synthesis between the approaches of social engineering used by progressivism and the already mentioned core principles of conservatism. In this area, conservatism has always been terribly deficient, and this also shows its blindness to the liberal principles that seduced it: somehow, from the 1970s onwards, the belief was that the control of economic levers was the only decisive factor in social management, and so it left all other areas to its opponents (whereby it most likely counted on securing social peace for itself). Leaving culture to the opponents (despite the large number of excellent conservative intellectuals) was, of course, a fatal mistake, because with this it left to the opponents not only the creation of the public sphere, but above all the construction of the mental/emotional structure of modern man and created moral automatisms that are already at the level of the unconscious in favour of the progressive agenda, and not only at the level of the individual, but of the broadest masses.

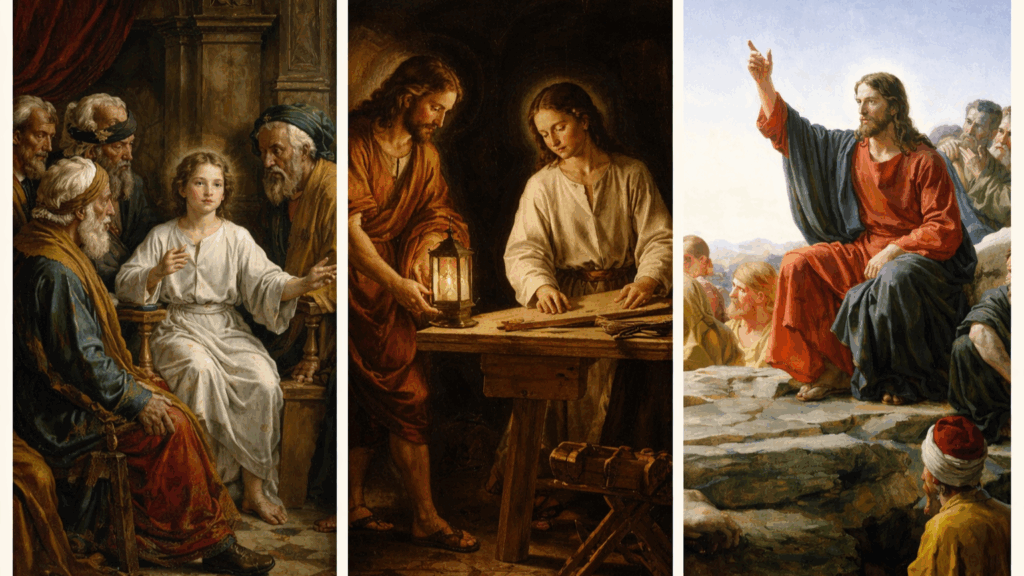

Conservatism and Christianity

Since conservatism is by definition bound to its cultural and civilizational particularity, even in relation to religion, Western conservatism must be bound to the metaphysics that shaped Western civilization in all respects: to Christianity. Even in the field of religion understood in this way, a phenomenon reminiscent of the already mentioned ideological syncretism appears. In the circles of the New Right (with honourable exceptions, of course) the tendencies are the following ones: transconfessionalism; cultural Christianity; and positivist atheism.

In the first case, it concerns certain tendencies that are introduced either by Jewish intellectuals or by intellectuals who are connected to Israel in one way or another. If it is irrefutably true that Western civilization is inextricably linked to Judaism, since Christianity itself was born from Judaism and forms the substantive core of Western civilization, on the other hand it is also irrefutably true that both Christianity and the synthesis of Jewish and non-Jewish elements in Western civilization mean both the metaphysical as well as the political transcendence of Judaism as manifested in the Torah and the Jewish state. Judaism’s main contribution to Western civilization was the soteriology of human time understood as a redemptive project, but this also led to the greatest spiritual tragedy in human history when the redemption was separated from the Church, understood as a mystical Body of the Redeemer. Therefore I think that the idea of Israel as the paradigm of the nation state must be discussed in the circles of conservative philosophy (we are not against this idea and we will translate Yoram Hazony’s books in Slovenian, but I think the idea itself needs to be supplemented philosophically). The spiritual core of Western civilization is not multi-religious, but mono-religious, and Judaism plays the role of one of its stimulating components.

In the second case, it is a question of the influence of secularism on all forms of thinking in modern times, including conservatism. Merely cultural Christianity is a doctrinal delusion that introduces relativism into the very foundation of Western civilization, as it robs it of its metaphysical dimensions and thereby automatically devalues all the achievements of the mentioned civilization, which were created precisely because of the energy that radiated from that spiritual foundation.

In the third case, it is an absurdity that only speaks of the fact that the ideological confusion of modern times has also penetrated conservatism. An atheist can be a conservative only in so far as it is in line with his own secularism: he can at most resemble a leisurely lover of antiquities or a museum curator. Of course, this is far from a worldview that can reverse the main trend of the modern world. A Western civilizational and Western cultural conservative must be a confessional Christian, a practitioner and a believer, the only question being asked is whether it is better to be a Catholic or a Protestant and whether a Western civilizational conservative can be an Orthodox. Western civilizational conservatism is inseparable from confessional Christianity, referring to the entire range of Christian spiritual history: from the Gospels and patristics to contemporary theology and practices. Here, however, it is worth noting this: regarding modern theology and practices—some of them are incompatible with Christianity as understood by conservatism. Especially those who strive to be attuned to the modern world and allow themselves to be seduced by liberalism, socialism and secularism to the point of questioning, if not denying, the very foundations of Christian doctrine.

Conservatism and the Europe of Nations

One of the key and seminal ideas of the entire right, from extremists to moderates, is the Europe of Nations. At this point, we are mainly interested in trying to shed light on the attitude of conservatism and then the New Right towards the idea of the Europe of Nations. A few months ago, a friend and recognized conservative thinker told me that the future of Europe could be twofold: either the United States of Europe or the Europe of Nations. The idea of the Europe of Nations is tempting, but it raises a number of questions. In the case of modern Europe, which built its geopolitical image based on the type of nationality that was formed in the 18th and 19th centuries and which is now experiencing its own identity crisis, when we talk about the Europe of Nations it is probably necessary to somewhat predefine the concept of nationality and the principle of integration that could form the Europe of Nations.

First of all, the New Right must therefore face the fact that, just as for everything we have mentioned so far, for the concept of the nation, it is also necessary to go to the roots and try to outline the morphology of this identitarian pattern. In my opinion, cultural anthropology can help us with this, as it shows us diachronically and synchronically the elements that make up this social structure. This is the key that allows us to extract from the concept of nationality the elements that can be used in the aforementioned synthesis, which is urgently needed in our time. Above all, these elements will show us the differences between the identity of an individual ethnic member and the modern atomized individual. In this case, it is a comparative research work that also has a practical purpose that can be included in the political theory of the European New Right.

The second aspect is related to the fact that, in fact, Europe does not need the theory of the Europe of Nations in a certain sense, since it has always been so since prehistoric times. European history is literally teeming with attempts to create a synthesis, but we must admit that so far they have all failed. The question is the following: how to create a synthesis that would be built from the bottom up and would allow individual entities as much sovereignty as possible. In this context, the question of the nation state, which is supposed to represent the opposite of the idea of an European federation (perhaps also a confederation), is raised with a great degree of relevance by most of the most recognizable modern conservatives for the nation-state (some go so far as to look for its allegedly non-European origin).

In the face of all this, the question arises as to whether the nation state really paves the most appropriate path for the establishment of the Europe of Nations, since Europe has many European peoples who do not have a nation state, others who have one, but have large minorities in other countries, etc. The question is, then, where to find the cohesive or centripetal force that would redirect all these centrifugal tendencies to a higher synthesis. Or in other words: the European nations need some higher common metaphysics that would connect them and also indicate common goals to them. The creation of nation states in the 18th and 19th centuries was not initiated by the idea of the Europe of Nations, so we need a new concept that would enable freedom, sovereignty and a commitment to common design and creativity. We therefore urgently need a redefinition of the concept of nation and also of the nation state.

Conservatism and the EU

In regard to all that has been said, it is quite clear that conservatism and the New Right cannot be in favour of an institution formation such as the European Union. If we proceed purely from theory, we can see that the European Union was successful in elements that are marginal in conservative political philosophy, if not opposed to it—in breaking down borders and in regulating economic relations. As for everything else, the European Union as an idea of unification is a completely failed project.

Of course, it is not possible to discuss all aspects here, so I will limit myself to the following: the European Union is primarily a product of what conservatism rejects the most: selective reductionism. Perhaps because it was conceived by the historical optimism of the Christian democrats and social democrats in an era defined by the Italian philosopher Augusto Del Noce as the ‘second Enlightenment’, the European Union was created on the basis of the absolutization of only one current of European spiritual history, namely by trying to erase and destroy all other dimensions of the European experience. This current could be called progressive secular positivism. All of this makes it essentially one dimensional.

‘The European Union openly acts against individual European identities’

Because of all this, essentially the only dimension on which the European Union rests is the set of values created by the Enlightenment. This is a consequence of the fact that the European Union was not created on the basis of a synthesis of the entire European experience, but on the basis of a special blindness that dictated that the horrors of the Second World War should be prevented at all costs from being repeated. Therefore, the European Union openly acts against individual European identities, uses autocratic methods, and imposes lifeless abstract patterns on the entire continent.

The European Union is dominated and actually ruled by an ideology whose goal is the destruction of all aspects of the European specificity: from its memory to its efficiency, ultimately also to the environment because the measures of the European Union are also disastrous in this respect. Therefore, the New Right must reject the European Union as it is now in its entirety. The only question that arises is related to the measure and methodology of this rejection, since there is no turning back in history. Not only is it impossible to return to the pre-Union era, to the period of the Cold War, but all of us, including members of the New Right, must admit that living together in a common loose super-homeland is desirable and alluring in its own way.

The New Right must therefore advocate for the path of reforms (but at the same time not rule out the possibility of exiting or abolishing the European Union if reforms could not take place). The New Right believes that the most appropriate thing would be to dissolve the European Union and rewrite the rules, thereby starting the process of a new association. The new Europe should, above all, give up its secular progressive, utopian soteriological dreams and focus on three aspects: on the European man, on the European cultural heritage, and on the protection of the European environment.

Conservatism and Central Europe

After we have defined the New Right, after we have defined its anthropology, after we have defined the community, and finally the wider geopolitical framework, it remains for us to define the specifics of the narrower particularity that connects us: Central Europe. The concept of Central Europe is usually associated with the Austro–Hungarian monarchy and the synthesis created in this area by the Habsburgs. However, we cannot forget that this entity was also destroyed or at least wasted by the Habsburgs. It may be, as many conservative thinkers point out, that the idea of empire and the idea of nation are incompatible. That is why the question of the possibilities of connection is all the more relevant when there is no longer an empire and the very idea of a nation is in need of revision.

This is irrefutable: around the middle of the 19th century, all the nations that belonged to the Austro–Hungarian Monarchy felt that they could not flourish as nations in that formation, and therefore worked more or less actively in favour of subversion; nevertheless, after its disintegration this formation left behind many properties that we acquired precisely in it, then became bound to them. It is probably a special law of historical becoming that when someone emerges from a certain context, he clings to the very elements that context offered him in order to form his new identity based on them. At the same time, there are a number of elements, for example in our spiritual engagement (for instance: expressionism in painting and art or secession in architecture), which in some way are an expression of the being of all of us and also affect us in return.

Also in relation to this issue, the New Right advocates the position that it is necessary to go to the roots and find common starting elements (for example, the type of family, which is key in the conservative understanding of sociogenesis) on the basis of which it is possible, taking into account the totality of our common and individual traditions, to design a paradigm of unification that will take place from below, which would be inclusive in the true sense of the word, and which would offer a model for the Europe of Nations, of which the Habsburg Monarchy was in some severely flawed way a predecessor.

This political definition could be used as a counterweight to the centralist, despotist and absolutist, often totalitarian tendencies of the European Union. Such an effort could assert a fundamental conservative disposition: the preference for the concrete over the abstract, which could also be called political realism. This may also be the key problem of the European Union: that it is led by people who are, so to speak, empirical foreigners in Europe. This is an area in which the Central European New Right can make a decisive contribution.

Related articles: