Nothing New Under the Sun: Contemporaneity and Conservatism

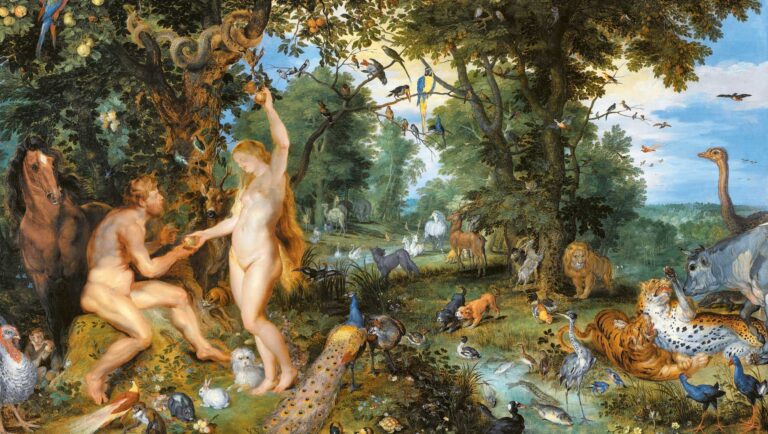

Conservatives often state, ‘Nihil sub sole novum est’, that is, there is nothing new under the sun, at least nothing that is not an actualized reinterpretation, ‘eternal return’ and reformulation of something old; a re-formation in the original sense of the word. The revolutionary tendency of conservatism is, accordingly, not something dedicated to the creation of a completely new reality.

What is in space and time certainly does not develop itself into infinity: all relevant experience proves that after a certain stage of development it turns into stagnation, then decline and destruction. In addition to death, the fact of birth is also constant: the two follow each other in an endless circle. Essential and realistic progress in this form does not exist in the sense of a ‘travelled path’, since all ‘travelled paths’ are mere illusions in relation to the absolute position of the Eternal. If the ancestors knew in transcendence—and all relevant investigations prove that they did—, the conservative then must go back to this soundest foundation, as an island lifting out of the flow of time. This everywhere evident basis of the ‘wisdom of the ancestors’ must be invoked if someone wishes to justify the need for preservation and conservation. From this point of view, there is nothing inherently tragic in the fact of change itself, since change is necessary. However, this is only true if we look at everything from the perspective of the Eternal. If there were only change—as the modernists claim—, and there were no Eternal, then change would be tragic. It inevitably ends in destruction, since the short rising stages are always followed by destruction, and to think otherwise is a utopia without any relevant experience. In such circumstances, even life itself is actually meaningless.

Today’s conservatives should respond to the problems of the modern world, however, they cannot act using the arsenal of Burke, De Maistre or Donoso Cortes alone. In this era, the pathway of renewal cannot consist in the restoration of monarchy—irrespectively of how many positive aspects real monarchies have had—nor the ‘re-Catholicization of Europe’, which is simply an illusion, considering the general premises of the modern mentality, which are deeply ingrained in the collective consciousness of the masses. Instead, conservative revolutionaries must adopt a specific inner attitude, which could be called ‘contemporaneity without modernity’. As Giorgio Agamben writes, ‘contemporariness inscribes itself in the present by marking it above all as archaic. Only he who perceives the indices and signatures of the archaic in the most modern and recent can be contemporary.’[1]

It follows from the individualized and fragmented nature of the modern age that conservatives must also find specific individual answers to problems posed by the crisis of modernity. However, the conservative ‘individualist’, in contrast to the modern one, does not break away from his transcendental basis in the fluid yet ever-present arkhé.

‘If there were only change—as the modernists claim—, and there were no Eternal, then change would be tragic’

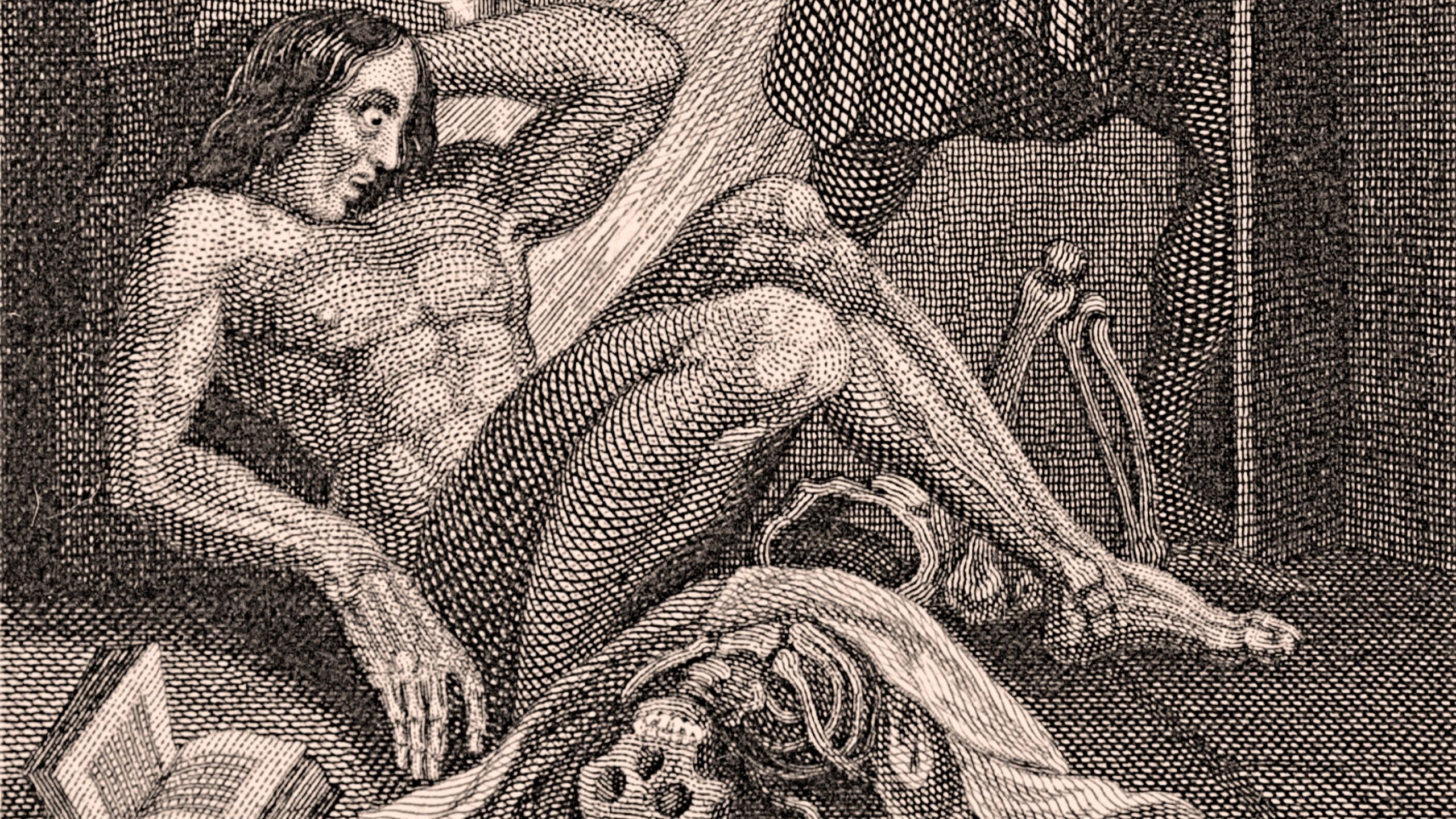

A revolutionary conservative author, Ernst Jünger, associates the modern state as the organ of modernity and its hegemony with Leviathan, the same monstrous figure that is also the central symbol of Hobbes’s work. The state always functions as an arm of an idea, an ‘executive apparatus’. Against Hobbes’s arch-liberal hope, in the modern context instead of order, Leviathan breeds chaos as a new control mechanism.

Jünger’s Forest Walker (Der Waldgang) is a subjectivity that consciously and reflexively distances itself from Leviathan and institutional ‘politics’, while remaining eminently ‘political’. This subject is not a politician but a person who, in terms of his whole being, acts against the all-encompassing regulatory activity of modern bureaucracy, being a counterbalance of the modern mass man (see Ortega Y Gasset). Placing himself outside the system of invisible and visible constraints, he does not participate in the almost universally mandated Cult of Reason. In a sense, it reminds us of Foucault’s ‘abnormal subjects’, all who cannot be brought under governmental supervision yet persist in being and therefore deviate from organized subjectivity. The Forest Walker however, as distinct from other, usually unreflexive, problematic subjects, is aware that the modern state is an inorganic construct, the product of drawing boards of rationalists who believe in the omnipotence of ‘Goddess Reason’. He thinks that the modern State, ‘the coldest of all cold monsters’ (Nietzsche), or the ‘Guardian State’ (Tocqueville) is intended precisely for the sake of ‘welfare and security’ with its oppressive apparatus, casting a shadow over true prosperity and true freedom.

Sociologist Émile Durkheim believed that Society is God. Unfortunately, this all too often translates into the dreadful and tyrannous thought that the State is divine, a clear aberration and confusion of two distinct concepts. Already this absolutization of sociology is suspect, but becomes even more so when used to justify technocracy—as in contemporary modernity—as the ideal form of government advocated for by Positivists such as Comte, Durkheim and others. Rebellion against such tendencies cannot take place without a solid point of convergence, and this can be none other than the concept of metaphysical transcendence—the only aspect of social reality that can be contrasted with politics—as inherently irrevocable and beyond institutionalization. In the present circumstances of our changed ecological condition, however, this does not mean some kind of shallow materialism (in the manner of the Marxists) or sentimental nature-worship (in the manner of the Romantics). Rather, the concept of transcendence must be deepened—even independently of individual theologies of religions and their specific circumstances that can be relativized by atheists—if we want to act successfully against modernity’s devastating materialism and associated ecological circumstances in a hostile climate. As Gai Eeton puts it:

‘…the simple believer of earlier times who knew very little yet possessed great faith could scarcely survive in the modern world, bombarded ceaselessly with the arguments of unbelief. Doctrinal knowledge has become almost essential for those who would hold fast to their religion against the tide. A hundred years ago a man could be a good Christian and remain so without ever having heard of St Augustine or Aquinas; ignorant faith was protected, and therefore sufficed. Today a Christian who does not have some knowledge of the doctrines upon which his faith is founded stands in mortal peril, unless protected by an impregnable simplicity.’[2]

‘Technology is becoming more and more totalitarian, a new mechanism of control’

This simplicity may be provided by an adherence to something that resists human designs. Differently put, the resistancy of real objectivity is the sole remaining guarantee of transcendence. Today, the expansion of the state apparatus and governmentality continues, but is approaching its culmination. In this spirit, that is, the announcement of the ‘fourth industrial revolution’ and ‘digitalization’, all of which fit into the logic of rationalization and rationalism, the world is becoming more and more virtual, and technology is becoming more and more totalitarian, a new mechanism of control. But the moment may still come, say those who are profoundly skeptical about the omnipotence of the ‘Goddess Reason’, as the story of the Golem, or clay man, reveals; the ‘Great Reset’ may easily reverse into wholesale civilizational collapse.

When even the Massachusetts Institute of Technology claims in an article that ‘The Collapse Is Coming’, conservatives must certainly be more aware than ever of the literal real content of the Apocalypse. A moment may come when the machine, almost unexpectedly, turns against its presumptive creator, while an already restive planet ends human dominion once and for all. At this moment of crisis, the guardian of true values (pushed to the fringes of society by democratism), the true conservative, must nonetheless make the decision and carry out the true preservation, ie a re-formation of values.

The full title of Mary Shelley’s famous Gothic novel is Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus. Victor Frankenstein, who creates a monster without a soul, is an exemplar of modernity. Mary Shelley, daughter of Mary Wollstonecraft, who first enthusiastically welcomed and then deeply condemned 1789, in the shadow of one of the ‘great moments’ of the Enlightenment—as a child of it— was eventually shocked by the inhumanity of the ‘great mechanism’ already in progress. Under the shiny armour of this great mechanism, the ‘state-machine’ (one most typical expression of the moderns) lacks spirit. The perils of industrialism were primarily recognized by ‘conservative anarchists’, who, as if consciously turning against the defining inertia of the age, were able to quietly, but still to an all-encompassing degree, rise in rebellion, which is not ‘drum-beating and flag-waving’ (Spengler) but a lightning-like insight into the ‘ruling ideas’ of the modern world. Today, true conservatives no longer seek to preserve the world’s status quo. They critique standardized reason, while rejecting the rationalistic channelling of thinking and all related ‘isms’. including those (such as technocracy) which do not market themselves as ideologies.

‘A conservative is someone who pays attention to essence instead of constantly changing phenomena’

For us, real objectivity, defined as resistancy-of-world to instrumentalization, is the guarantee of the political after and beyond politics. For some people, it may seem that conservativism nowadays has more in common with anarchism than ‘reactionism’, but this is only true on a superficial level. Even today, there are people in modern, Western societies, although scattered and often unaware of each other’s existence, who favour the organic over the mechanical, who favour the cult of quality over the cult of quantity—even through revolution (see László Németh)—while advocating for a natural order. A conservative is someone who pays attention to essence instead of constantly changing phenomena. Against the passive consumption offered to people by the dominant currents of modernity, there is here an affirmation and perhaps the promise of active value creation, in harmony with Nature. In Spengler’s terms, there are always those who are on the side of culture against mere ‘civilization’. While conservative revolutionaries reject all-encompassing centralization, they are not liberals. They affirm values, realities and worlds of life that cannot be derived from (falsely) universalist systemic principles. They acknowledge a natural, hierarchical order of life, the rights to existence of the true individuum, and the organically formed and functioning family, which instead of the ideological indoctrination of the global media channels, feeds the reanimated ‘wisdom of the ancestors’. They affirm the principle of tradition and also the pluralism of different traditions, the right to existence of sovereign nations with distinct cultures, values and ways of life to exist side by side, while affirming the contingency which shall forever make the technocrat’s utopia—AI surveillance cameras and all—forever a utopia.

[1] Giorgio Agamben, What Is an Apparatus?, trans. David Kishik and Stefan Pedatella, Stanford University Press, 2009, 50.

[2] Gai Eaton, The King of His Castle. Choice and Responsibility in The Modern World, The Bodley Head, London, 1977, 14.

Read more from Zoltán Pető: