With the U.S. election just days away, the world is collectively holding its breath, though one imagines it might exhale into a stiff drink by now. This isn’t mere hyperbole: who lands in the Oval Office will drastically shape the foreign policies of countries around the globe. With Donald Trump, one can usually take a stab at what’s coming next—something disruptive, likely loud, and definitely memorable. But Kamala Harris? Well, that’s where the crystal ball fogs up a bit, doesn’t it?

The question of what a Harris administration’s foreign policy would be is rather like asking a cat its views on quantum mechanics: you’re unlikely to get much clarity. There’s been a rather large absence of any discernible worldview to distinguish her from her boss, Joe Biden. Indeed, one might say her foreign policy is as elusive as the Hungarian summer—everyone has vague expectations, but no one is quite sure what it’ll look like when it finally arrives.

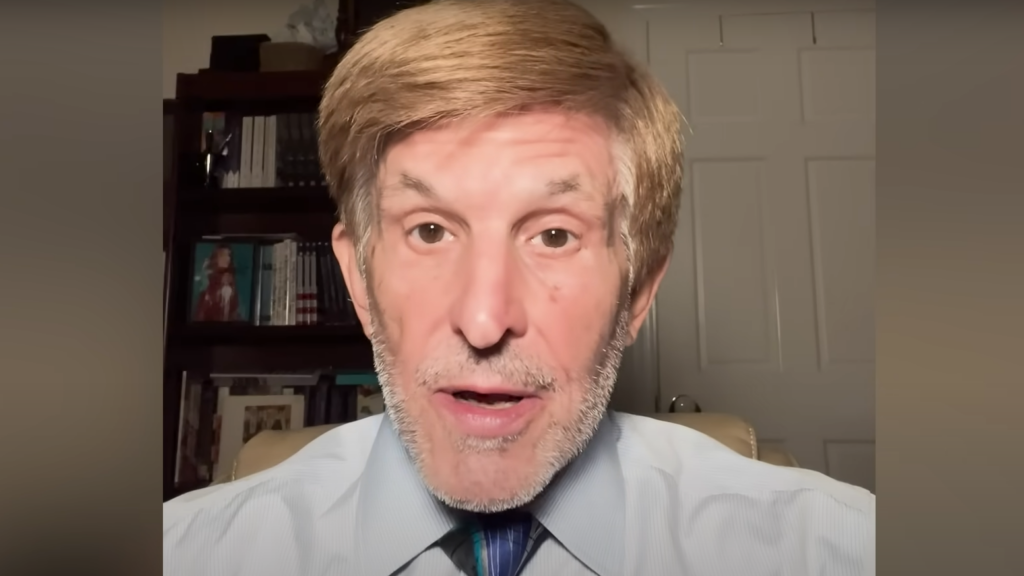

There is, however, one tried and true method to figuring these things out: look at the man who’s likely to be calling the shots behind the scenes. In this case, that would be Philip H. Gordon, her current national security advisor and the author of Losing the Long Game: The False Promise of Regime Change in the Middle East (2020). Gordon’s influence on Harris is already strong, and he’s a far more interesting character than the usual Beltway apparatchik. He’s a scholar, a critic of past U.S. interventionism, and has enough gravitas to make one suspect that a Harris administration might actually deviate from the tired, old obsession with foreign policy intervention. Then again, this is Washington we’re talking about. Donald Trump had H.R. McMaster as a national security advisor—a man who authored the critique of how poor presidential leadership led to the failed U.S. war in Vietnam. He was nonetheless succeeded by John Bolton, who is known for his relentless desire to bomb Iran.

Gordon, for his part, is a man of experience—which in Washington is a polite way of saying he’s been in the game long enough to have been deeply involved in or exposed to disasters. From his stint in the Clinton administration working on European affairs to his role as special assistant and coordinator for the Middle East, North Africa, and the Gulf region to President Barack Obama, Gordon has seen it all—and, crucially, written about it all too. Losing the Long Game is a scathing critique of the United States’ penchant for regime change in the Middle East, which has, time and again, gone horribly wrong.

‘Her administration might be much more cautious about military intervention’

Gordon’s central thesis is that regime change efforts of various stripes, while often seductively dressed up as the ‘solution’ to all of Washington’s problems, have invariably left America worse off. He goes through a roll call of U.S. misadventures in the region, from the toppling of Iran’s Mohammad Mosaddegh in 1953 to the more recent train wrecks in Iraq, Libya, and Syria. The takeaway? U.S. policymakers don’t seem to know how to stop. Instead, they seem permanently under the spell of wishful thinking, believing that with just one more war, one more intervention, the Middle East will magically become a stable, democratic paradise (though one can assume this line of thought extends to other regions). And like the loyal assistant to an eccentric inventor, they’re consistently shocked when things don’t go as planned.

So what does this tell us about a potential Harris presidency? For one thing, her administration might be much more cautious about military intervention, especially in the Middle East—at least in the Middle East. Gordon has been advising Harris for years, and his influence shows. He’s no fan of the heavy-handed regime-change fantasies that characterized the George W. Bush years, and it’s fair to assume Harris won’t be either. Her administration may take a more restrained approach—one that favors diplomacy and multilateralism over sending in the Marines at the first whiff of trouble. Or, at least, that’s what we might hope.

Take the Israel-Palestine conflict, for instance. Gordon has been an advocate of a two-state solution, which, in Washington, makes him somewhere between unorthodox and radical, depending on the mood of the moment. His recent comments have been less than charitable towards Israel’s handling of its security. He’s criticized settlement expansions in the West Bank and argued that Israel’s ongoing occupation of Palestinian territories isn’t exactly the path to long-term peace. If Harris follows his lead—and let’s be honest, she likely would—her administration could push Israel a bit harder to find a sustainable political resolution rather than just giving them a blank cheque for military action. One imagines that would go down about as well with Benjamin Netanyahu as a lead balloon.

‘A Harris administration could push Israel a bit harder to find a sustainable political resolution’

Yet, if Gordon’s views suggest that Harris would shy away from military adventurism, that doesn’t mean she’s about to become an isolationist. Gordon’s brand of realism isn’t the dour, cynical kind of John Mearsheimer-style ‘realpolitik.’ No, he still thinks the United States has a vital role to play on the world stage, and that the country will continually stand ‘on the right side of history.’ But that role should come with a hefty dose of humility. America, he argues, needs to realize it can’t fix every problem, and it certainly shouldn’t try to by force.

Of course, Gordon is no dove. He still believes in the importance of American engagement in the world—he just wants it to be done with a bit more finesse. He advocates for the version liberal internationalism that promotes democracy and protects human rights without becoming entangled in another Iraq-style quagmire.

But in the context of an increasingly multipolar world, where the old Washington hands fret about America’s declining global influence, it’s hard to imagine a Harris administration truly embracing restraint. The temptation to double down on maintaining U.S. primacy, especially as the world gets messier and more competitive, might prove too strong.

After all, Gordon may argue for caution, but his worldview is still deeply embedded in the belief that the United States must lead. In a Democratic establishment terrified by the specter of rising authoritarianism, like Russia to China, to even populist movements in Europe, it’s unlikely that any Harris administration would sit idly by as the liberal international order unravels. There’s a deep anxiety running through the foreign policy class these days—particularly among Democrats—that they’re witnessing the twilight of American hegemony. And when a superpower feels its status is slipping, restraint often gets tossed out of the window in favor of reasserting dominance, no matter how much Gordon’s writings preach otherwise.

Let’s not forget that Biden himself came into office talking about restoring America’s leadership on the world stage, and his administration hasn’t exactly held back in ramping up great power competition with China. Could a Harris administration really resist the pressures from within her own party to ‘confront authoritarianism abroad,’ especially when those same voices are screaming bloody murder over the survival of democracy at home? It’s all very well to talk about restraint, but when Washington’s foreign policy elite believes the sky is falling, they’re rarely satisfied with subtle diplomacy and multilateral forums. America’s strategic culture favor proactive engagement when confronted with the threat of regional instability.

So, while Harris might give a few nods to Gordon’s cautious realism, the odds are good that her administration would find itself drawn into the same patterns of trying to ‘do more’ to uphold American influence and counter rising powers. Diplomacy, cooperation, and common sense are all well and good, but in an era of perceived decline and the rise of new challengers, the liberal internationalists in Washington have a strong record of concluding that a little less restraint—and a little more intervention—is exactly what the moment calls for.