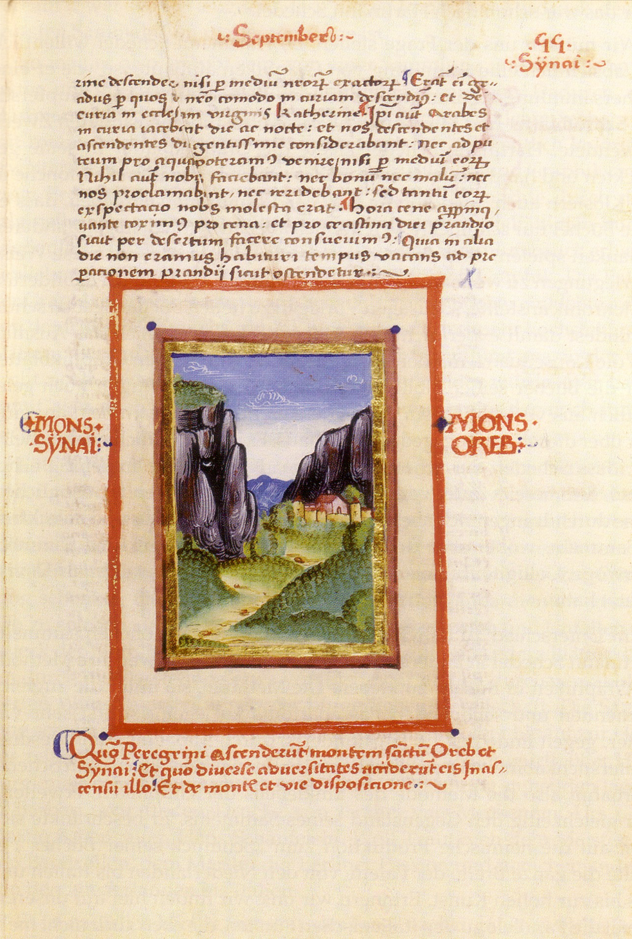

The heyday of pilgrimage was in the 11–12th centuries, when pilgrims began to flood into Europe and the Holy Land. The world expanded, with scheduled ships, guidebooks, and guides awaiting those arriving from across the sea. Yet the importance of the Orthodox rite of St Catherine’s Monastery at the foot of the 2,300-metre Mount Sinai (Jebel Musa, also known as Horeb) in the Sinai Peninsula grew only after the loss of Jerusalem in 1187 and the fall of the Latin states in the Holy Land in 1291. The monastery was located 10 days’ walk south of Cairo but was more easily accessible from the port city of Alexandria, which from 1328 onwards attracted pilgrims with the promise of a papal indulgence, too. The first chapel was built in the early 4th century by Empress Helena, who found the cross of Christ on the spot where Moses saw the Burning Bush and received the tablets of the Ten Commandments, and where a cave recalled the prophet Elijah’s forty days’ refuge on Mount Sinai.

The monastery was built under Roman Emperor Justinian (reigned 527–565 AD) and became a veritable fortress with its two-metre-high walls, as well as a holy place for the Jewish, Christian, and Muslim faiths. A copy of a letter signed by Prophet Muhammad in 623, in which he takes the monastery under his protection, is still preserved in the building. It is the oldest monastery in the world to have survived in this way, where, among other things, the oldest 4th-century Greek-language manuscript of the Bible, the Codex Siniaticus, has also been preserved (now in the British Library).

The first surviving description of a pilgrim was written by a lady of Hispanic origin named Etheria from the 380s AD. At the part about Mount Sinai, she immediately quotes the relevant passage from the Book of Moses: ‘Loose the latchet of thy shoe, for the place whereon thou standest is holy ground…’ (Exodus 3:5). She did not yet know of the body of St Catherine of Alexandria preserved here, but by the 9th century the news of Catherine’s relic was already widely known. The first eyewitness was a German monk, Thietmar, in 1217, who wrote for pages about his experiences here, referring to the dangers of the desert journey, such as robbers, lions, and snakes.[1] Christian pilgrims were attracted to the site as much by the memory of St Catherine as by the Old Testament relics.

The veneration of St Catherine was widespread in both the Western and Eastern Churches, and she became one of the most popular female saints of the Middle Ages. As one of the Fourteen Holy Helpers, she was prayed to against sudden death. She was also venerated in the Hungarian royal dynasty; the daughters of Kings Béla IV and Louis the Great bore her name, and even the mother of Béla IV’s Byzantine wife is said to have come from the family of St Catherine. It is of no coincidence that she was favoured by dynasties, as legend has it that she herself was not only of noble but of royal descent, too. Her martyrdom is recorded in detail in her legend. Catherine refused to take part in idolatry during the visit of the Roman Emperor Maxentius (r 306–312 AD) to Alexandria. The Emperor then ordered 50 pagan philosophers to persuade Catherine, but as a result of the debate with her, all of them converted to Christianity instead. She did not escape execution, however, and although she miraculously survived the rack, legend has it that when she was beheaded and her head fell off, not blood but milk flooded from her body, then angels carried her corpse to Mount Sinai and buried it there. This is also the story of Hungarian Franciscan author Pelbartus Ladislaus de Timișoara (d 1504), who dedicated four sermons to her in his manual.

‘The veneration of St Catherine was widespread in both the Western and Eastern Churches, and she became one of the most popular female saints of the Middle Ages’

The journey to the far-flung pilgrimage site was costly and time-consuming, and only wealthy laymen could undertake it, in addition to the clergy. Among the Hungarians, it was Stephen Lackfi, Voivode of Transylvania, who could reach the monastery of St Catherine in 1376, having pledged two villages to cover the cost of the journey. He chartered a boat in Venice and sailed from there to Alexandria. From there, he reached the Holy Land overland via the Sinai Peninsula and then sailed back from Beirut via Rhodes.

Hungarian Franciscan provincial head Gábor Pécsváradi spent years in the Holy Land before publishing his guidebook in Latin in 1520, in which he devoted a whole chapter to the sights of Mount Sinai. He was aware that the angels guarded Catherine’s body on the top of the mountain, whose outline was carved into the rock and could still be seen in his time. Following Moses’ footsteps, he climbed to the top of the mountain, counting the steps that led up to it.[2]

Among the Hungarian pilgrims, however, the most detailed is the journey of John Lászai (also Lázói) (1448–1523), canon of the Cathedral of Gyulafehérvár (today’s Alba Iulia, Romania), from 1483.[3] John had previously studied in Italy, had close contacts with the humanists of his time, and as a result, could join the pilgrimage organized by Swiss Dominican monk Felix Fabri (1438–1502). Fabri was perhaps the most famous pilgrim of the century—the abridged German version of his 1500-page Latin itinerary became popular reading. According to Fabri’s records, the immediate destination of the nearly 290-day pilgrimage was Jerusalem, then he returned to Venice via Egypt through the Sinai Peninsula.

In July 1483 they landed in Jaffa and were guided through the shrines of the Holy Land by the superior of the Franciscan monastery on Mount Sion and his fellow monks. Together with his companions, John visited the sites of Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Bethany, and Jericho, bathed in the Jordan River, prayed on the Mount of Olives, that is, visited the most important venues in Jesus’ life. In Gaza, in an unexpected turn of events, he met Mameluke warriors of Hungarian origin: ‘There were some Hungarians among them who asked if there were any Hungarian pilgrims among us…When they met John, they were very happy, sat down in our tent, and ate and drank with us. They even drank wine, but only in secret.’

The Transylvanian canon, together with some of his daring companions, then followed in the footsteps of the Holy Family and visited the holy places of the Copts and the Egyptian Christians. Fabri described in detail how the European pilgrims visited the monastery of St Catherine on 26 September, and how they were shown the relics of St Catherine in the main church and the chapel of the Burning Bush. One of the highlights of the visit was the improvized poem by Canon John in honour of the martyr:

‘Take the crown, the immortal ornament of thy virgin life,/ I beseech thee, o martyr and reputed Catherine,/ Take, o holy one, the pains taken for thee,/ And intercede for thy own, though unworthy.’

From there they sailed to Alexandria, and on 11 October in Cairo the pilgrims’ hostel was once again visited by Mamelukes, apostate Christians from various nations, including Hungarians. The friendship between Canon John and the Egyptian Hungarians became so direct that he received invitations to visit their families one after the other, where, before holding a merry farewell feast, he secretly married the couples and baptized the children. The whole group of pilgrims benefited from the friendship he had developed with the Hungarian Mamelukes, who became their permanent companions in Cairo.

‘The friendship between Canon John and the Egyptian Hungarians became so direct that he received invitations to visit their families one after the other’

On 15 October the pilgrims were received by the Mameluke Sultan in his palace in the Citadel. It was not surprising, as he was at war with the Ottomans, so he sought the alliance of the European powers that were also at war with them. King Matthias had sent an envoy to the Sultan as early as the 1470s, while Mameluke envoys arrived at the Hungarian court in 1489 and 1490. After a sightseeing tour of Cairo, the Christian pilgrims visited the Pyramids of Giza as well and then sailed on the Nile to Alexandria.

In his work Fabri speaks highly of his Hungarian companion: ‘Among them was the court chaplain of the Hungarian King, John Lászai, a highly educated man, who remained my companion even when I visited the tomb of St Catherine…He was a born and bred Hungarian, he did not understand a word of German, but he knew Latin, Slavic, and Italian well, in addition to Hungarian. A noble and virtuous man, an excellent orator and mathematician.’ Indeed, Fabri did not exaggerate, as an unparalleled record of Canon John’s patronage was preserved in the Cathedral of Gyulafehérvár. He had the cathedral’s Romanesque north hall rebuilt in Renaissance style and consecrated as a chapel in 1512. The reliefs on the façades of the chapel depicted ancient mythological and Old Testament figures and saints. The walls of the chapel were decorated not only with carved coats of arms but also with his verse inscriptions. Poetry accompanied him throughout his whole life, and his last work was an epitaph for his own tomb. Sometime between 1500 and 1508, he made another pilgrimage to the Holy Land, but no record of it survived.

At the end of his life, he moved to Rome and became the Hungarian-speaking confessor of St Peter’s Cathedral. He had a gravestone erected for himself in the Santo Stefano Rotondo, later the national church of the Hungarians in Rome, a replica of which was placed in the Lászai Chapel in Gyulafehérvár in 1999 with the support of the Hungarian government. The Roman church, dedicated to the protomartyr deacon Saint Stephen, has been closely linked to Hungarian history since 1454, when the Hungarian Palatine monastery was built next to it. It is no coincidence that it was also the titular church of Cardinal József Mindszenty (†1975), Archbishop of Esztergom. Canon John Lászai was buried here in 1523, whose marble slab bears a life-size depiction of him. His epitaph is a rare relic of the European culture of the medieval Hungarian clergy:

‘Wanderer, if you see that he who was born by the frozen Danube now rests in a Roman tomb, do not be surprised: Rome is the home of us all.’

[1] Denys Pringle (ed), Pilgrimage to Jerusalem and the Holy Land, 1187–1291, Farnham-Burlington, 2012, pp 95–133.

[2] Béla Holl (ed and transl), Pécsváradi Gábor: Jeruzsálemi utazás, Budapest, 1983.

[3] Imre Lázár, ‘Egy erdélyi zarándok Egyiptomban. Lászai János 1483-as útja a Szent Család nyomában’, Magyar Egyháztörténeti vázlatok, Vol 12, 2000, pp 105–125.

Related articles: