World leaders are meeting in Baku for COP29, where lofty climate pledges clash with national interests and the divide between rich and poor nations remains unresolved. Hungary should seize this moment to push for realistic energy solutions that safeguard its national interests.

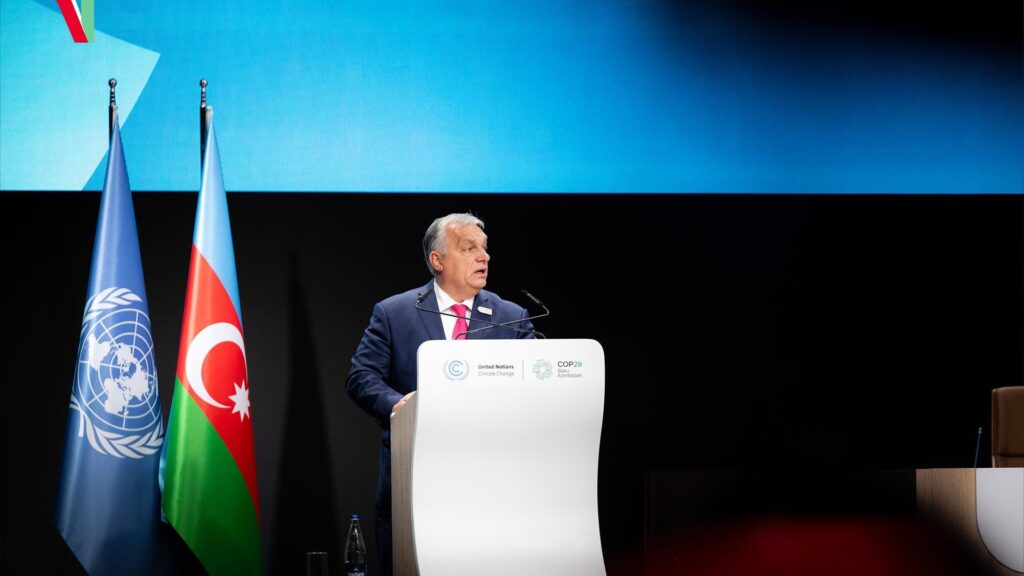

Quite a few world leaders have descended upon Baku for COP29—the latest in the United Nations’ well-intentioned but often lumbering climate conferences. This year’s iteration, hosted in Azerbaijan, a proud petro-state, comes with a fitting dose of irony: a major oil and gas exporter now charged with leading discussions on how to curb humanity’s fossil-fuel habit. As ever, there will be high-minded talk, impassioned speeches, and, if history is any guide, a remarkable shortage of concrete outcomes. Nevertheless, Baku promises to address some crucial points, chief among them the thorny issue of climate finance—a recurring headache that has long pitted the wealthier nations against the less fortunate.

Climate finance sits at the heart of COP29, with renewed urgency to finally establish a framework that doesn’t falter on arrival. For the uninitiated, climate finance refers to funding allocated to support initiatives that address climate change—particularly by reducing greenhouse gas emissions (mitigation) and adapting to its effects (adaptation). Wealthier nations in the Global North, who have historically contributed the most to carbon emissions and now have decades of entrenched green policies, are quick to outline ambitious targets for carbon emission reductions. The problem is that developing countries of the Global South have contributed significantly less to historical emissions but are increasingly asked to shoulder the financial and technological burdens of a climate transition.

Thus the necessity of climate finance: the Global South requires public, private, or international investments, directed from the wealthier nations in the Global North, to assist with the costs of transitioning to low-carbon economies and building climate resilience.

In theory, everyone agrees that this is fair and necessary. Wealthier nations have promised for over a decade to mobilize $100 billion a year for developing countries. The problem is that actual delivery has been patchy, with funds often mired in bureaucracy or overshadowed by vague pledges. At this point, the problem has gotten worse. For many experts, COP29 represents a do-or-don’t-bother moment in climate finance, as estimates now place the necessary funding well beyond the original $100 billion, with some projections as high as $1 trillion annually to meet the needs of the developing world.

‘How to advance economically without being penalized for relying on the same development pathway once enjoyed by the West?’

It is in this context that the decision to host the conference in Baku stands out. Azerbaijan and other energy-rich countries in the Global South find themselves pulled between the pressures of industrialized nations and the realities of their own economic dependencies. As fossil-fuel producers, these countries have less room to manoeuvre in transitioning to renewables. There is also the issue of timing: despite rising climate action across Europe and North America, most developing nations have yet to industrialize on the same scale and, thus argue, with some legitimacy, for a more gradual shift. For them, the question remains: how to advance economically without being penalized for relying on the same development pathway once enjoyed by the West?

COP29 thus presents an opportunity for richer nations to make good on those promises by crafting a more robust financial plan. It also presents an opportunity for fossil-fuel-producing countries to argue that certain energy sources—such as natural gas—should be considered a necessary transitional energy source, rather than a dirty one like coal. Yet the conference also lays bare the question of whether this time will truly be different.

For Hungary and other Central European nations, COP29 also serves as a measure of how far their own energy strategies can be influenced by broader EU climate ambitions. Hungary’s energy matrix still relies heavily on natural gas, and any aggressive EU climate policy could introduce economic challenges for smaller states that cannot simply swap out fossil fuels without significant disruptions. As Hungary observes the discussions in Baku, it has a particular interest in advocating for solutions that don’t leave Central European economies straining to keep up with their Western counterparts—or leave it ruined, as is increasingly the case in Germany. With climate policy still an uneven patchwork across the EU, COP29 may add another layer to Hungary’s balancing act between EU commitments and national energy security.

Yet while COP29 is hailed as a ‘make-or-break’ moment, it’s likely that pragmatism and political caution will dampen the enthusiasm for transformative action. Climate finance, as ever, will likely see pledges inflated by idealism but tempered by budget constraints. The developing world’s hopes for a $1 trillion commitment will, in all likelihood, settle for something far smaller and more ambiguous, leaving many poorer nations to grapple with the realities of underfunded green initiatives. And while Baku may showcase rhetorical unity, the divide between North and South, rich and poor, will persist as a reminder that climate policy, for all its grandeur, is still bound by each nation’s own economic priorities.

‘For wealthier countries in the Global North, the climate agenda offers an opportunity to entrench their geopolitical and economic dominance under the guise of green leadership’

Ultimately, COP29 will likely reaffirm what we’ve long known about global climate diplomacy: nations, despite their collective rhetoric, will prioritize their own interests. For wealthier countries in the Global North, the climate agenda offers an opportunity to entrench their geopolitical and economic dominance under the guise of green leadership. By pushing ambitious climate goals that require costly transitions, they can maintain their technological edge, secure their economic systems, and ensure that the playing field remains tilted in their favour. For the Global South, however, these policies can feel less like solutions and more like an extension of historical imbalances—another framework where the rules are written to the advantage of those who already hold the power. The predictable result in Baku will be a continuation of these tensions, with watered-down agreements designed more to preserve face than to bring about a transformative global shift.

For countries like Hungary, the path forward lies in navigating this uneven landscape with pragmatism. As an EU member balancing its energy reliance on natural gas with the bloc’s push for renewables, Hungary must carve out a strategy that secures its energy needs without undermining its climate commitments. Pursuing nuclear energy could provide a viable middle ground, offering reliable and relatively low-emission power while reducing dependence on gas imports. At the same time, Hungary could explore investments in regional energy cooperation, leveraging its position in the Danube region to shape a strategy that prioritizes energy security alongside incremental progress toward climate targets. As Baku will likely demonstrate, the global framework may be more symbolic than substantive, leaving individual nations to forge their own paths—paths that align with their realities rather than the lofty but often impractical goals of global summits.

Related articles: