This article was originally published in Vol. 4 No. 4 of our print edition.

The Case for a Danubian Compact

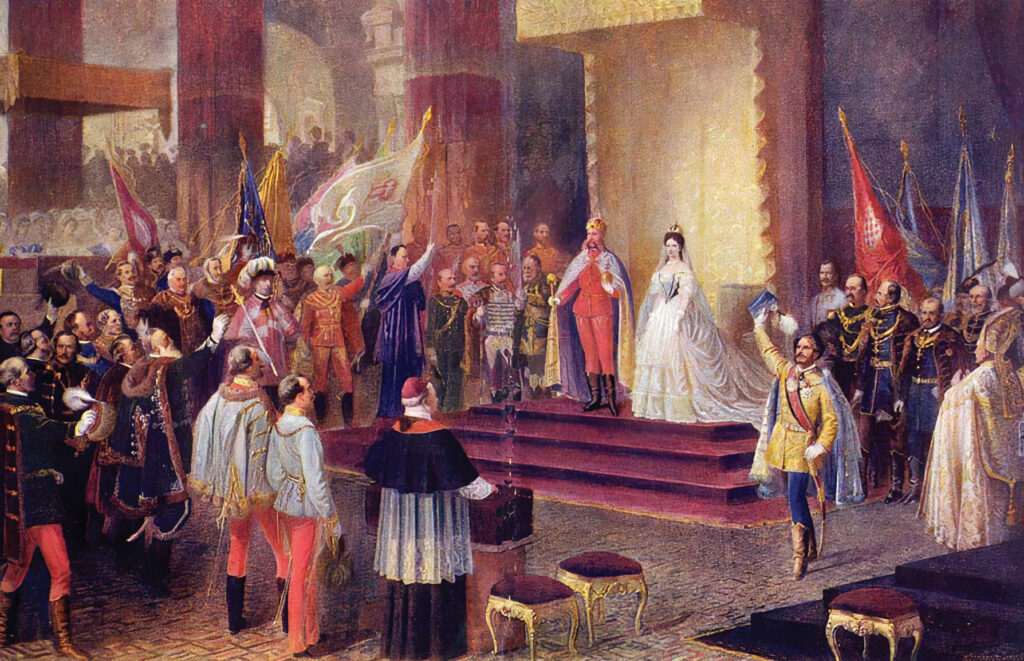

The Habsburgs are back—or so the headlines jokingly claim.1 Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s political manoeuvring earlier this year resulted in a new EU Parliament group, dubbed Patriots for Europe, initially composed of a motley crew of Central European populists. As one journalist noted, the group’s initial makeup of Hungary, Austria, and the Czech Republic encompass the old Habsburg Empire’s heartlands. Amongst diehard Habsburg loyalists, there are whispers of an imperial restoration—though without the double-eagle insignia and imperial pomp (for now).

For most political observers and commentators, this is all presumably merely part of Orbán’s intra-EU politicking and the political right’s efforts to reassert itself in the EU. However, this development, along with others, raises a fascinating question: what if, in some form, the Habsburg Empire really is returning? Let us run with that idea for a moment. What if the ghosts of Europe’s most famous dynasty are reawakening—not as an imperial monarchy but as a pragmatic political and economic compact? With the Visegrad Group (or Visegrad Four, V4) stumbling and strained by divergent approaches to Russia, the Ukraine War, and EU relations, Central European states are in search of a healthy dose of reinvention.

Enter the Danubian Compact—a new minilateral arrangement among Hungary, Austria, and Slovakia that could pick up where the V4 left off, breathing new life into Central Europe’s geopolitical and economic aims. The Danubian Compact could serve as a modern, flexible framework for cooperation, focusing on shared economic interests, energy security, infrastructure development, and more. What if the real future of Central Europe does not lie in resurrecting the past, but in reimagining it for a new era? The pieces are there, the question is whether the leaders of these nations are willing to make that leap.

The Rise and Fall of the Visegrad Group

As Central Europe adjusts to the challenges of the twenty-first century, it is important to consider the regional arrangements that have defined its recent history. Among these, the Visegrad Group stands out and merits close attention.

Established in 1991, the V4 was born out of a shared vision for the future among four (then three) Central European nations—Hungary, Poland, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia (back then, the Czech Republic and Slovakia were still united as Czechoslovakia). Emerging from the ashes of communist rule, these countries sought to shed the Soviet legacy that had dominated their post-war history and reintegrate themselves into Western Europe. The Visegrad Declaration—signed in the Hungarian town of Visegrád, a symbolic nod to historical ties between Central European states—was a political statement of intent: ‘It is the conviction of the states-signatories that in the light of the political, economic and social challenges ahead of them, and their efforts for renewal based on principles of democracy, their cooperation is a significant step on the way to general European integration.’2

The shared goals of the V4 were clear: faster economic development, enhanced regional security, and a successful transition to democracy. Membership in NATO and the EU became the focal points of cooperation, and by presenting a united front, the four countries managed to accelerate their collective integration into Western political and economic structures. In the early years, this cooperation paid significant dividends. By 1999, Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic had all successfully joined NATO, followed by Slovakia in 2004. The same year, all four gained EU membership, cementing their return to Europe after decades of Soviet control. The Group’s strength during this period lay in its ability to leverage collective bargaining power, as individually none of the V4 members could have achieved such progress at the same pace. In many ways, the V4 succeeded in its original purpose—bridging the gap between Central Europe and the West.

The V4 continued to assert itself within the EU, working together on various issues. Things began to change, however, with the 2015 refugee crisis. V4 countries aligned themselves against the EU’s common immigration policy, coming out staunchly against mandatory quotas for refugee distribution.3 As expressed by Czech researcher Klára Votavová: ‘Even more than the economic crisis, the V4 was welded together by the migration crisis of 2015–2016. At the time, the alliance stood firmly against the EU’s decision to distribute 120,000 refugees from various wars among the EU Member States…This was the crisis that transformed this region of imitators who did nothing more than adopt Western European solutions into a region of rebels. Strong regional players, especially Hungarian PM Viktor Orbán, took to depicting Central Europe as a bastion of ‘true’ European and/or Christian values standing up against western decadence, leftist experiments, and Muslim hordes. Orbán’s claims of a ‘rational’ Central Europe resonated strongly in Hungary and beyond. In the Czech context, they were echoed (with varying degrees of radicalism) by Andrej Babiš, Miloš Zeman and prominent members of most political parties…’4

This united stance, largely spearheaded by Hungary and Poland, positioned the V4 as a politically conservative bloc within the EU, resistant to deeper integration and working to uphold national sovereignty.5 This alignment extended to other fronts, from LGBTQ laws to agricultural policy and shared resistance to the EU’s Green Deal.6 For a time, it looked as though the V4 had solidified itself as a stable and unified bloc capable of challenging the dominance of Western European interests and ideological preferences within the EU.

Yet even during its most successful periods, the V4 was and remains plagued by inherent weaknesses. Key amongst these is the lack of institutionalization: unlike other regional alliances such as the Benelux or the Nordic Council, the V4 has never been endowed with a permanent secretariat or decision-making body. The Group’s only formal institution, the International Visegrad Fund, was established to support cultural, educational, and scientific cooperation among the member states.7 While this entity has funded numerous projects and initiatives that strengthened regional ties at a grassroots level, its limited scope, focus on soft diplomacy, and lack of political influence render it unable to address other deeper issues. As such, V4 cooperation has remained informal, relying heavily on ad-hoc meetings between heads of government and lower-level officials.8 This leaves the V4 vulnerable to changing political dynamics in member states and makes it difficult to sustain long-term projects or initiatives.

The shift began in Slovakia in 2018, with the dramatic fall of Prime Minister Robert Fico. The country entered a period of political instability, with a series of governments led by prime ministers Peter Pellegrini, Igor Matovič, Eduard Heger, and interim leader Ludovit Odor. During the administrations of Matovič and Heger, from April 2021 to the end of 2023, Slovakia adopted a firmly pro-European stance. Yet the truly defining change for the V4 came in 2022 with the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The war, along with political changes between 2022 and the present, has resulted in a deep fracture in the Group.

Start with Hungary. While Budapest has condemned Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and supported some EU sanctions, it has also opposed more extensive sanctions, particularly those affecting energy, citing its dependence on Russian oil and gas as a landlocked country. Hungarian Foreign Minister Péter Szijjártó effectively communicated Budapest’s position in June of this year: ‘It is impossible to ensure Hungary’s energy supply without Russian energy resources and that has nothing to do with politics or ideology but is rooted in plain facts of physics.’9 This was not an exaggeration: at the time of Orbán’s fourth re-election in 2022, Russia provided Hungary with 90 per cent of its gas supplies and 65 per cent of its oil.10 And while Budapest has undertaken several efforts to reduce this dependency since the war’s outbreak, full-scale replacement at a realistic and reasonable cost cannot be accomplished in only two years.11 More broadly, Orbán’s government has consistently advocated for a negotiated settlement to the conflict and has maintained a firm stance against supplying arms to Ukraine. This reflects Hungary’s broader strategy of prioritizing national interests and economic stability over alignment with broader Western policy on Russia.

In stark contrast to this is Poland. Warsaw, regardless of the government of the day, maintains a consistently anti-Russian stance stemming from its long historical experience of Russian domination—including partitions, Soviet occupation, and Cold War influence. Additionally, Poland—even under the right-wing Law and Justice Party (PiS)—views Russia as a major threat to its security and sovereignty, especially in light of recent Russian aggression in Ukraine. This position was supercharged by the October 2023 elections, which marked a significant political turning point, as it saw the defeat of PiS and the rise of a new, politically centrist coalition led by former Prime Minister Donald Tusk. The new government quickly initiated a programme of ‘de-PiS-ification’, aiming to reform the media, judiciary, and economy to align with EU standards while also distancing itself from the previous Warsaw–Budapest alignment.

The Czech Republic, meanwhile, firmly repositioned itself in the political centre with the early 2023 election of former general Petr Pavel as president. Pavel’s main competitor in the race was Andrej Babiš, who, similarly to Orbán in Hungary, ran on a platform advocating for a negotiated peace in Ukraine. Late in the campaign, Babiš even questioned the country’s commitment to NATO, stating in a January 2023 interview, ‘I want peace; I don’t want war. And under no circumstances would I send our children or women to war.’12 Pavel’s decisive victory in the runoff at the end of January 2023 aligned Prague with Warsaw as a firm supporter of EU and NATO backing for Ukraine.

Finally, in Slovakia, Robert Fico staged a remarkable return to power in the September 2023 elections, running on a platform that closely resembled Orbán’s approach in Budapest. Since then, he has taken Hungary’s side on the matter of Ukraine. In January 2024, Fico stated that the war in Ukraine would only end with Kyiv ceding territory to Russia. ‘There has to be some kind of compromise. What do they expect? That the Russians will leave Crimea, Donbas and Luhansk? That’s unrealistic.’13 He has likewise consistently reiterated that he will veto Ukrainian entry to NATO, with the last such pronouncement being made in early October of this year.14

In sum, the V4 is now firmly divided. At a summit of the Group in Prague in February 2024, the divide was on full display. While Poland and the Czech Republic called for increased military support for Ukraine, Hungary, joined by Slovakia, advocated for an immediate ceasefire and criticized the EU’s sanctions policy.15 To quote one observer, ‘a canyon-like divergence has become so apparent that it wouldn’t be out of order to speak of a V2+V2’.16

While the Group continues to meet and express a nominal commitment to cooperation on various other issues, the reality is that the V4 has lost its former unity. Depending on who one asks, the Visegrad Group is either ‘on life support’,17 ‘in hibernation’,18 or ‘irrevocably ruptured’.19 This situation will not improve. While the Ukraine War deepened the Group’s divisions, the real deathblow comes from an older, more fundamental conflict: the clashing geopolitical aspirations of Poland and Hungary.

The Commonwealth Awakens?

Just as the Habsburg Empire seems to be ‘returning’, so too is the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth be reawakening. At first glance, this proposition may sound utterly fantastical, but in Central and Eastern Europe, history has a way of looping back. And when one considers the geopolitical currents at play today, the re-emergence of this centuries-old power structure does not seem after all far-fetched.

Let us start with a quick reminder of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Formed in 1569, it was one of the largest and most powerful states in Europe for over two centuries—a multi-ethnic, multi-faith union stretching from the Baltic to the Black Sea. At its height, the Commonwealth even managed to occupy Moscow in 1610 during the Smutnoye vremya (the Time of Troubles). The Commonwealth’s eventual decline came as its neighbours—Russia, Prussia, and Habsburg Austria—picked apart its remaining territory in a series of partitions towards the end of the eighteenth century. Yet the memory of the Commonwealth and its rivalry with Russia remains potent for both nations.

Fast forward to the early twentieth century, and Poland found a new champion in Józef Piłsudski. Born in 1867 to a family of Polish nobles, when much of Poland was still a part of the Russian Empire, Piłsudski grew up resenting Moscow’s Russification policies and the suppression of Polish language and culture. By 1918, when Poland declared its independence, Piłsudski became the country’s de facto leader and head of state. For Piłsudski, securing Polish independence and prevailing in the Polish–Soviet War (1919–1921) was not only about defending Poland’s borders, but it was also about protecting the idea of a free and independent Central Europe—Poland especially—against Russian imperialism. Thus, his vision for Poland’s place in the world—Międzymorze (Between the seas)—revolved around two major geopolitical concepts: Intermarium and Prometheism. These ideas were crafted to counter Russian power and ensure Poland’s independence in a hostile geopolitical neighbourhood.

‘The Danubian Compact could serve as a modern, flexible framework for cooperation, focusing on shared economic interests, energy security, infrastructure development, and more’

Intermarium (the Latinization of Międzymorze) envisioned a federation of Central and Eastern European states stretching between the Baltic and Black seas—a strategic alliance of states that would buffer against both Russia and Germany. In other words, a recreation of a Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. But just as attempts to reform the Habsburg Empire into a federation in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries failed due to nationalism and competing priorities, so too did Intermarium run into nationalist sentiment and the fear of Polish domination.20 Piłsudski later attempted to revise the Intermarium concept by excluding Ukraine and Belarus—which at that point were firmly under Soviet control—and instead extending the hypothetical state to include Finland, the Baltic states, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, and Greece. In short, Intermarium was to be a Central European union, stretching between the Baltic, Black, and Adriatic seas. This effort also failed due to the virulent nationalist sentiments and competing interests of the interwar period.

Piłsudski’s other major concept, Prometheism, aimed to weaken Russia by supporting the independence movements of various non-Russian peoples within the Russian Empire. By promoting national sovereignty in Ukraine, Belarus, and the Caucasus, Piłsudski sought to dismantle the Russian imperial structure from within. While Intermarium focused on building a coalition of external states, Prometheism was an effort to disrupt Russia from the inside, ensuring that its imperial reach would not extend to Poland’s doorstep.

Both of these concepts reflected Piłsudski’s deep understanding of the precarious position Poland occupied in Europe. Sandwiched between two historically expansionist powers—Germany and Russia—Poland needed to secure alliances to survive. For Piłsudski, this meant not only forging military and diplomatic ties, but also supporting the aspirations of other nations that were similarly threatened by Russian dominance. Conflicts like the Polish–Soviet War, therefore, were not just a fight for territorial integrity and to secure independence, but also an opportunity to shape the political landscape of Eastern Europe in Poland’s favour.

Critics might argue that such early-twentieth-century concepts are long outdated and irrelevant to modern geopolitics. However, geopolitics has a habit of recycling its fundamental principles. Take the enduring influence of Halford John Mackinder’s ‘Pivot Area’/’Heartland Theory’ from 1904 as an example. Mackinder’s argument—that whoever controls Eastern Europe controls the ‘Heartland’ of Eurasia, and from there, the world—had a profound effect on how Anglo-American geopolitical strategists and foreign policy thinkers perceived Eurasia. Researcher Oliver Krause put it as follows: ‘the conjunction of the pivot area concept and the heartland theory as a monolithic system in US perception…influenced the strategic narrative of US foreign policy, especially in interpreting threat scenario analyses by the military…The extension of the heartland was almost coterminous with the state territory of the Soviet Union. The once geographically defined heartland had become synonymous with a political entity and a catchphrase in the US strategic narrative.’21

Although George Kennan, dubbed ‘the architect of containment’, never explicitly referenced to heartland theory or the pivot area concept, these geopolitical frameworks clearly influenced the strategy’s acceptance among US policymakers and the public. Their alignment was crucial: both early geopolitical theories and containment focused on the same region and shared the same goal—defending the democratic world from an autocratic power based in the heartland. This understanding still informs US foreign policy today, as evidenced by various attempts in recent years to revive containment as a foreign policy strategy and apply it to China and Russia.22 If Mackinder’s ideas can remain relevant for well over a century, why not Piłsudski’s? Geopolitical concepts do not expire as quickly as people assume. Instead, they evolve with the circumstances of the day, offering frameworks that endure through cycles of power.

Much of Piłsudski’s Intermarium vision is alive and well in the form of the Polish-led Three Seas Initiative.23 Launched in 2015, the Three Seas Initiative brings together thirteen countries located between the Baltic, Adriatic, and Black Seas—precisely the geographic area Piłsudski had envisioned for his federation. The initiative focuses on developing energy, infrastructure, and digital connectivity to strengthen regional cooperation, encourage economic growth, and reduce dependence on external powers, particularly Russia. While the Three Seas Initiative does not include formal military cooperation, it has become an increasingly important pillar of Poland’s foreign policy, building regional resilience against outside influence.24 Moreover, the Initiative has seen growing support from the United States, with Washington viewing it as a bulwark against Russia’s attempts to dominate its neighbours.25

Similarly, Prometheism can be seen playing out in the context of the Ukraine War. By supplying military aid, welcoming millions of refugees, and lobbying for stronger Western backing for Kyiv, Poland is not only assisting its neighbour in its fight for independence but also strategically weakening Russia’s influence in the region. Strengthening Ukraine’s resilience also directly serves Poland’s long-term interests by creating a buffer state that helps guard against Russian encroachment, echoing Piłsudski’s goal of a free and sovereign Ukraine as a bulwark against Russian aggression. Additionally, Warsaw played host to the first meeting of the Free Nations of Post-Russia Forum, an organization dedicated to transitioning Russia ‘from an authoritarian imperial state to a voluntary agreement of free, independent and democratic countries that can provide a decent standard of living for their own citizens, as well as sustainable peace in Eurasia’.26 All this aligns closely with Piłsudski’s vision of empowering non-Russian nations to dismantle Russian imperialism from its periphery.

Russia, for its part, also sees the Ukraine War as part of a broader struggle with Poland dating back to the Commonwealth. For those who consider this to be an overstatement, consider American journalist Tucker Carlson’s interview with Russian President Vladimir Putin from earlier this year. In the interview, a large chunk of which was a long historical lecture, Putin touched upon Poland as follows: ‘The southern part of the Russian lands, including Kiev, began to gradually gravitate towards another “magnet”—the centre that was emerging in Europe. This was the Grand Duchy of Lithuania…But then there was a unification, the union of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of Poland…For decades, the Poles were engaged in the ‘Polonization’ of this part of the population: they introduced their language there, tried to entrench the idea that this population was not exactly Russian, that because they lived on the fringe (u kraya) they were “Ukrainians”…So, the Poles were trying in every possible way to polonize that part of the Russian lands and actually treated it rather harshly, not to say cruelly. All that led to the fact that that part of the Russian lands began to struggle for their rights…’27

Much can be said and argued about this passage, along with Putin’s broader historical narrative, including aspects of it that are factually incorrect or misleading. What is beyond doubt, however, is that for Putin the war in Ukraine is part of a greater struggle for influence that dates back centuries, with Poland seen as a rival force actively shaping the identity and destiny of the lands that Russia claims as its own. After all, what does it say that Ukrainian, as a language, is linguistically somewhere between Russian and Polish?28

If Moscow regards Poland as a key player in a centuries-long geopolitical contest over Eastern Europe, then the present moment is one of consternation for Russia: modern-day Poland is closer to achieving the wealth and power of the Commonwealth era than ever before. Start with Poland’s economy. When the Iron Curtain fell in 1989, Poland was on the brink of bankruptcy, burdened by an inefficient agricultural sector, poor infrastructure, and an economy no larger than Ukraine’s. At the time, Czechoslovakia and Hungary were seen as the ex-communist countries with the brightest futures, while expectations for Poland were low. Poland, however, had a unique advantage: a distinct cultural attitude toward Europe. Adam Biliński summarizes this attitude in his review of Marcin Piatkowski’s Europe’s Growth Champion: Insights from the Economic Rise of Poland:

‘Culturally, Poland has benefited from a social consensus emphasizing the “return to Europe”. Communism was treated as a historic aberration and a foreign (Russian) imposition. Hence, a large majority of society wanted the country to join the European Union (EU) and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), institutions in which, according to this narrative, Poland should and had a right to participate. In this regard, Polish society was willing to make the necessary sacrifices to join the EU and thus achieve the symbolic status of a “normal” European country. These sacrifices included the adoption and implementation of Western institutions and practices (strengthening of the rule of law; implementation of modern banking, financial, and educational systems; reduction of corruption; etc.). The process turned out successful and contributed to a positive feedback loop leading to even faster growth.’29

Thus, the implementation of rigorous economic shock therapy in the early 1990s, along with wholesale political reform, was more patiently understood and accepted than in other post-Soviet countries. Market-oriented reforms, such as removing price controls, limiting wage growth, cutting subsidies, and balancing the budget, were introduced. Though the initial impact was harsh, with a deep recession in 1990–1991, Poland began to recover and grow shortly thereafter. Its economy has expanded continuously ever since, with a significant boost following its EU accession in 2004. Per World Bank data from 2023, Poland is now one of the top-performing post-Soviet states (in terms of GDP per capita).30 In fact, by 2021, before the Ukraine War broke out, Poland was almost three times as wealthy as Ukraine despite being significantly poorer when the USSR broke up. To date, Poland remains one of the few countries to escape the middle-income trap.31

Unlike other European states, however, Poland has sought to translate economic success into hard military strength, especially following the outbreak of the Ukraine War in early 2022. In July of that year, then-Defence Minister Mariusz Błaszczak promised that Poland would develop ‘the most powerful land forces in Europe’.32 Any doubt as to Warsaw’s position was swept away by then-Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki on the eve of the country’s independence day celebration that year: ‘The Polish Army must be so powerful that it does not have to fight due to its strength alone.’33 That is to say, Poland seeks a military so strong that it can deter others from fighting it.

In practice, this has meant massive investment into its armed forces. As one Politico headline put it, ‘Meet Europe’s Coming Military Superpower: Poland.’34 The precise details of this remilitarization are beyond the scope of this article. What matters is that Poland’s military build-up is, to quote a Center for European Policy Analysis study, ‘on a grand scale and moves [the country] to a different league in European defense. The armed forces are now on track to become the continent’s most capable land force, and the anchor of the European Union (EU)/NATO’s Eastern Flank capable of deterring and defeating Russia…for ground-based deterrence and defense against Russian incursions in Europe’s Eastern Flank, Europe will increasingly rely on Poland…’35 As a result, if this programme is successful, Warsaw will be in a position to ‘reshape European security in ways fundamentally aligned with Poland’s interests’.36

Across the Atlantic, the United States has been strongly supportive of this shift. As early as 2003, Poland was being dubbed ‘America’s protégé in the east’.37 Both Washington and Warsaw were aligned in supporting the then- recently independent states between Russia and Poland, anchoring Ukraine and Lithuania to the West, supporting NATO expansion, and encouraging the pro-Western movement in Belarus.38 Furthermore, a ‘defining tenet of Polish strategic culture, which chimes with current American security thinking, is a disposition to favour proactive engagement when confronted with the threat of regional stability’.39

As a result, scholars Marcin Zaborowski and Kerry Longhurst noted the following at the time: ‘Differences within Europe over the US stance on Iraq have served to expose the weakness of the French and German vision of Europe’s role in the world, as seen in their relative isolation. In turn, it is possible to hypothesize that Poland, as one of the most vociferous and consistent supporters of American foreign policy and the solidarity between the US and Europe, is likely to be among the group of states shaping the new Europe and its foreign policy.’40 Twenty years later, this hypothesis has become a reality. To quote an unnamed, senior US Army official in Europe who spoke to Politico in late 2022, ‘Poland has become our most important partner in continental Europe’.41 But perhaps most notably, the weakening of the Franco-German axis and the strengthening of Poland has been observed by the other potentially determinant actor in the region: Hungary.

The Danube Region as a Keystone Region

The Bálványos Summer Free University and Student Camp, more commonly known as Tusványos, is an unlikely hub of Hungarian foreign policy. Each year, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán steps up to deliver his worldview sermon, offering a blend of geopolitical analysis and nationalist rhetoric to a mix of university students and political elites—all against the backdrop of the Transylvanian mountains. What started as a casual summer gathering has morphed into a stage where Orbán outlines Hungary’s future, critiques the EU, and makes headlines with his musings.

This year’s speech was particularly noteworthy, especially given Orbán’s comments on Poland and European foreign and defence policy:

‘European policy-making has also collapsed since the beginning of the Russo-Ukrainian War because the core of the European power system was the Paris–Berlin axis, which used to be inescapable: it was the core and it was the axis. Since the war broke out, a different centre and a different axis of power has been established. The Berlin–Paris axis no longer exists—or if it does, it has become irrelevant and liable to be bypassed. The new power centre and axis comprises London, Warsaw, Kiev/Kyiv, the Baltics, and the Scandinavians…Changing the centre of power in Europe and bypassing the Franco–German axis is not a new idea—it has simply been made possible by the war. The idea existed before, in fact being an old Polish plan to solve the problem of Poland being squeezed between a huge German state and a huge Russian state, by making Poland the number one American base in Europe. I could describe it as inviting the Americans there, between the Germans and the Russians. Five per cent of Poland’s GDP is now devoted to military expenditure, and the Polish Army is the second largest in Europe after the French—we are talking about hundreds of thousands of troops. This is an old plan, to weaken Russia and outpace Germany. At first sight, outpacing the Germans seems to be a fantasy idea. But if you look at the dynamics of the development of Germany and Central Europe, of Poland, it does not seem so impossible—especially if in the meantime Germany is dismantling its own world-class industry.’

‘By expanding its grand strategy to encompass this regional approach, Hungary can not only preserve but enhance its strategic influence’

There are several important takeaway points here. First, Orbán now recognizes as reality what Zaborowski and Longhurst hypothesized two decades ago could happen: the ‘weakness of the French and German vision of Europe’s role in the world’ has given way to Poland assuming a stronger, possibly determinant, role in European foreign and defence policy. Second, Orbán is all but explicitly recognizing the Intermarium—note the recognition of an axis that comprises ‘Warsaw, Kiev/Kyiv, the Baltics and the Scandinavians’ and the reference to ‘old Polish plan’ that addresses ‘the problem of Poland being squeezed between a huge German state and a huge Russian state’. Third, Orbán points out that this is all possible because Germany is committing economic suicide, owing to an unwise energy policy that left it dependent on Russian energy exports (now sanctioned owing to the Ukraine War), banned nuclear energy, and made the wrong bet on renewables.43 Germany’s weakness has created an opening for Poland. Fourth, the new twist to Intermarium, Orbán is saying, is the involvement of the United States as a strategic off-shore balancer that can lend its strength and support to Poland. This involvement provides Poland with the external backing needed to counterbalance both Germany and Russia, reinforcing its leadership role in Central and Eastern Europe.

In other words, Orbán is pointing out that, with US support, Poland’s geopolitical influence can now extend beyond its immediate region, fundamentally altering the power dynamics in Europe and challenging the traditional Franco-German dominance in shaping the continent’s defence and foreign policy. In short, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth may as well be back. This, in turn, has dramatic consequences for Hungary and the other V4 countries. Orbán opines that Poland’s strategy has driven it ‘to give up cooperation with the V4. The V4 meant something different: the V4 means that we recognize that there is a strong Germany and there is a strong Russia, and—working with the Central European states—we create a third entity between the two. The Poles have backed out of this and, instead of the V4 strategy of accepting the Franco–German axis, they have embarked on the alternative strategy of eliminating the Franco–German axis.’44

This is a colossal statement, especially from the Hungarian prime minister. The geopolitical purpose of the V4, in Orbán’s telling, was to link Poland with the countries to its south—the Danube region—thus creating a small bloc of countries that could ‘soft balance’ (to use a scholarly term) by embracing a level of strategic autonomy and restraint. However, with Poland’s strategic shift toward dismantling Franco-German power and aligning more closely with US power, the geopolitical purpose of the V4—pragmatic cooperation within the framework of a strong Germany and Russia—has been effectively undone. The V4, as a geopolitical entity, is now defunct. It may still have a role in coordinating alignment on certain issues within the EU—migration, farming policy, and the like—but otherwise, its time is running out. Orbán hinted as much in July when he said that the Group still has ‘some life left in it’—not exactly an optimistic prognosis.45

Where, then, does this leave Hungary and the other Visegrád states? Later in his Tusványos address, Orbán explains that Hungary—given the changing regional and global order—now requires an explicit long-term grand strategy, rather than a short-term strategy and that such a strategy is currently being refined by the office of the prime minister’s political director, Balázs Orbán (no relation). The essence of this grand strategy, Viktor Orbán indicated, is one of ‘connectivity. This means that we will not allow ourselves to be locked into only one of either of the two emerging hemispheres in the world economy. The world economy will not be exclusively Western or Eastern. We have to be in both, in the Western and in the Eastern. This will come with consequences. The first. We will not get involved in the war against the East. We will not join in the formation of a technological bloc opposing the East, and we will not join in the formation of a trade bloc opposing the East. We are gathering friends and partners, not economic or ideological enemies. We are not taking the intellectually much easier path of latching on to someone, but we are going our own way. This is difficult—but then there is a reason that politics is described as an art.’46

Hungarian grand strategy, in other words, will be one of Hungary being a keystone state—a concept introduced by US Naval War College professor Nikolas K. Gvosdev in 2015, which I then myself introduced to the Hungarian policymaking community in 2022 in the pages of this very publication.47 The concept has since been taken up enthusiastically by Balázs Orbán, who has expanded upon and refined the concept—particularly in his 2023 book, Hussar Cut: The Hungarian Strategy for Connectivity.48 For those who are unfamiliar with the concept of a keystone state, the brief explainer I wrote two years ago still holds up: ‘Keystone states, Gvosdev explains, give “coherence to a regional order—or, if it is itself destabilized, contribute to the insecurity of its neighbors”. These states, “located at the seams of the global system”, are connectors and mediators—they serve as gateways between regions, blocs, civilizational groupings, and so forth. They possess integrative power, the “ability to generate positive relationships”. As Gvosdev elaborates, this can come from a variety of sources: “the existence of important transit and communications lines that are vital for trade traversing its territory; the position of the state to promote regional integration and collective security among its neighbors; its role as a point of passage between different blocs, or its position overlapping the spheres of influence of several different major actors, thus serving as a mediator between them; or its willingness to take up the role as a guaranteed barrier securing neighbors from attack’.49

While I still firmly believe that Hungary retains the potential to be the keystone state of Central and Eastern Europe, this role must now evolve in response to the shifting geopolitical and diplomatic realities. The foundation of Hungary’s keystone status remains intact, but the dynamic challenges and changes of the past two years highlight the need for broader cooperation. Hungary can still fulfil this crucial role, but not in isolation. Rather, it should aim to anchor a keystone region, where a network of Central and Eastern European states works in tandem to balance between East and West.

The concept of a keystone region is itself amorphous; Gvosdev introduced it in a 2020 essay for Baku Dialogues, specifically in the context of the Silk Road region, but did not define it concretely.50 This leaves room for significant interpretation, particularly as the concept becomes increasingly relevant in a multipolar world. For the time being, a ‘keystone region’ can be understood as a geographical area that plays a pivotal role in shaping broader regional or global dynamics due to its strategic location, resources, or connectivity. Unlike individual keystone states, which contribute to the coherence and stability of their immediate surroundings, a keystone region acts as a hub through which multiple political, economic, and cultural interactions flow. These regions are characterized by their capacity to connect various power blocs, facilitate the movement of goods, ideas, and influence, and even stabilize neighbouring areas by serving as a crossroads of critical infrastructure and geopolitical interests.

In the context of the Danube region—which spans Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe, with Hungary located at its centre—this concept holds significant relevance. The Danube River not only connects several European countries but also serves as a natural corridor linking Western Europe to the Black Sea. The region’s importance extends beyond individual state actors; it is a transnational space in which energy supplies, trade routes, and political alliances converge. The region has historically been a meeting point of great powers, from the Habsburg Empire to the Ottoman and Russian empires, and today it continues to function as a bridge between the European Union and its eastern neighbours. As a keystone region, the Danube plays a crucial role in European stability, integration, and security, particularly in balancing the interests of NATO, the EU, and non-EU states.

Thus, by expanding its grand strategy to encompass this regional approach, Hungary can not only preserve but enhance its strategic influence, ensuring the region collectively serves as the stabilizing force in the evolving global order. This does not represent a departure from Hungary’s established role, but rather a natural progression in adapting to the complexities of the current international landscape. Historians will detect notes of something older in this approach. They are right to do so: a keystone region strategy is, in fact, precisely the strategy deployed by the Habsburg Empire for navigating the complexities of a fragmented, competitive geopolitical landscape.

A. Wess Mitchell explains in his magisterial The Grand Strategy of the Habsburg Empire, the Habsburgs faced more enemies than any other European power and lacked many of the advantages that underpinned the success of other empires, such as economic wealth or military prowess.51 Surrounded on all sides by powerful neighbours, the Habsburgs could not afford to rely solely on military solutions, as they were often financially stretched and dealing with a multi-ethnic populace. Yet they endured for centuries in Europe’s most dangerous neighbourhood by developing a grand strategy of carefully sequencing conflicts and using alliances, treaties, and diplomacy to buy time, concentrate resources, and neutralize their greatest threats one by one.

The idea of Hungary anchoring a keystone region, rather than standing alone as a keystone state, echoes the Habsburg strategy of using the broader region to its advantage. As Mitchell argues, the Habsburgs understood that their survival depended on forming and maintaining coalitions with other states, often turning potential adversaries into de facto allies through diplomacy and shared interests. The Habsburg Empire, surrounded by the Ottoman, Russian, and Prussian powers, could not engage in open conflict on all fronts. Instead, it relied on leveraging alliances and treaties to neutralize threats. Hungary today finds itself in a similar position with shifting global dynamics. By broadening its vision to encompass a keystone region, Hungary can emulate the Habsburgs’ method of managing multiple pressures through regional cooperation, ensuring that the burdens of balancing East and West are shared.

One of the core elements of the Habsburg strategy was its pragmatic use of time, a concept that Hungary must also adopt in its regional leadership. As Mitchell notes, the Habsburgs mastered the art of ‘buying time’ in geopolitical competition. They did not attempt to defeat all their enemies simultaneously; instead, they staggered their conflicts, allowing them to focus their limited resources on the most pressing threat at any given moment. Similarly, Hungary’s anchoring of a keystone region would allow it to sequence its geopolitical challenges. By coordinating with regional allies, Hungary could confront issues incrementally, preventing any single conflict or issue from overwhelming its capacities. This approach of time manipulation—where Hungary can set the pace of engagement and mobilize its alliances—aligns directly with the Habsburg approach of outlasting stronger powers through strategic patience.

Finally, Mitchell’s observation that the Habsburg Empire thrived despite its internal diversity and external pressures speaks to the potential of Hungary to coordinate a similarly diverse keystone region. The Habsburgs ruled over a multi-ethnic empire, navigating the complexities of a polyglot society by fostering cooperation among its disparate parts. This ability to manage such regional fragmentation while projecting strength externally is something Hungary must learn.

The Cace for a Danubian Compact

The Habsburg Empire’s attempts to reform its structure in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were ultimately unsuccessful, but their essence—a strategy of marshalling a coalition of smaller states to buffer against and maintain balance between powerful neighbours—is taking on new life today. Far from abandoning its role as a keystone state, Hungary’s shift to anchoring a keystone region would mark the next evolution of its strategic role—one that mirrors the Habsburg model of regional leadership, where the empire’s longevity was secured through collective resilience rather than solitary dominance. Just as during the Habsburg period, the Danube region stands at a crossroads between East and West, North and South. And just as the Habsburgs sought to maintain their empire by promoting cooperation and autonomy across multiple ethnic and political entities, a new framework for cooperation among today’s Danubian states could help these nations navigate the complex geopolitical landscape they face.

Budapest already recognizes this reality. Viktor Orbán has spoken of the need for Hungary to ‘explore other opportunities of cooperation among pro-sovereignty states’ and has suggested a possible Austrian–Hungarian–Slovak–Serbian cooperation scheme.52 This arrangement, he argued, would not necessarily replace the V4 but would appear alongside it, reflecting the shifting dynamics of the region and offering a more focused framework for collaboration.

This notion lays the groundwork for what I propose should be the ‘Danubian Compact’—a new minilateral focused on the Danube region that would begin as a flexible, ad-hoc arrangement similar to the early V4. The Compact would start with Hungary, Austria, and Slovakia—three nations whose current governments share similar ideological and political views, particularly on national sovereignty, balancing foreign relations, and interacting with the EU. These countries would be well positioned to start this initiative. But how could such a compact be realized? A few initial steps could set the foundation for long-term success.

The first should be a summit meeting of national leaders to discuss the key principles and objectives of the Compact. Much like the 1991 Visegrad Declaration, this summit should culminate in a formal declaration outlining the goals of the Compact. Infrastructure development, economic growth, and increased regional connectivity must be the priority, setting the stage for greater political and economic collaboration down the road. Following the summit, the second step would be to launch an annual ‘Danube Forum’. This forum would bring together political figures, business leaders, think tanks, policy thinkers, and civil society representatives to discuss and promote the Compact’s principles and goals, along with recent developments, ongoing challenges, and potential and future opportunities. By fostering discussions on key issues, the forum would help strengthen ties among member states and build momentum for broader regional cooperation.

A third initiative would be the creation of a ‘Danube Fund’, modelled after the Visegrad Fund but with a sharper focus on shaping a shared political and geopolitical understanding of the region. This fund would support projects aimed at increasing connectivity, promoting cross-border collaboration, and fostering a common identity for the Danube region. It would also provide a platform for dialogue on how to manage relations with larger powers such as the United States, the EU, Russia, China, and others. Finally, each nation’s chamber of commerce (or its equivalent) should sign a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) to launch the ‘Danubian Private Enterprise Partnership’. This public–private partnership would raise awareness of the Compact within business communities and support projects that align with its objectives, particularly in areas such as infrastructure development and cross-border trade. In time, the partnership could evolve into a separate regional ‘Danubian Chamber of Commerce’.

As the Compact evolves, there will be potential for growth beyond the initial three-member core. The Czech Republic and Slovenia are natural candidates for future inclusion, should their political climates become more conducive to cooperation. Serbia, while a prime candidate for initial inclusion—due to its geographical position, historical ties to the region, and the ideological leanings of the current government—presents a more complicated case. As a non-EU member state and with a foreign policy often viewed suspiciously by the United States and the EU for its pro-Russian leanings, Serbia’s inclusion requires further careful consideration, discussion, and dialogue. Nonetheless, its strategic importance along the Danube and its historical connection to Austria–Hungary make it a valuable potential partner.

One of the Compact’s early focuses should be on improving regional connectivity, both in terms of physical infrastructure and economic ties. In this regard, the port of Trieste offers an excellent opportunity. Hungary’s acquisition of a port terminal in Trieste positions it to play a pivotal role in facilitating trade between Central Europe and global markets—particularly the Indo-Pacific region. The irony that Trieste was once the maritime gateway of the Habsburg Empire is not lost here—it underscores the historical continuity of this region’s strategic importance and provides a fitting symbol of the potential for a renewed Danubian partnership.

By building on shared interests in infrastructure, energy security, and regional stability, the Danubian Compact could chart a course for Central Europe’s future that echoes the cooperative strategies of its past. The Habsburgs understood the value of leveraging the strengths of multiple nations to balance larger powers, and the same logic holds true today. A successful Danubian Compact would not only strengthen its members but also serve as a stabilizing force in a complex and rapidly changing world.

The Afterlife of Empires

As unlikely as it seems, two of Europe’s most influential empires—the Habsburgs and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth—are experiencing a revival, not as monarchies, but through the re-emergence of their strategic legacies. The Habsburgs’ grand balancing act, rooted in regional cooperation along the Danube, finds new life in the proposed Danubian Compact. At the same time, Poland’s Three Seas Initiative and its strategic backing of Ukraine mirror the ambitions of the old Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

The Danube region, once the backbone of the Habsburg Empire, is reasserting itself as a keystone for Europe’s future stability. Whether through economic collaboration or strategic partnerships, today’s efforts reflect the same logic of regional power balancing that sustained empires in the past. The strategies that once defined the region are being repurposed for modern realities. Empires may fall, but their influence lingers. History is cyclical, and the region’s leaders now have an opportunity to reshape the Danube’s role in Europe’s future.

NOTES

1 Matthew Karnitschnig, ‘Habsburg Empire Strikes back’, Politico (12 July 2024), www.politico.eu/article/habsburg-empire-viktor-orban-patriots-for-europe-hard-right-european-parliament-hungary-austria-czech-republic/; Anthony J. Constantini, ‘Habsburg Ghosts of Austria-Hungary Hover over the Fears of Central Europe’, Brussels Signal (5 July 2024), https://brusselssignal.eu/2024/07/habsburg-ghosts-of-austria-hungary-hover-over-the-fears-of-central-europe/.

2 ‘Visegrad Declaration 1991’, www.visegradgroup.eu/documents/visegrad-declarations/visegrad-declaration-110412.

3 ‘Joint Statement of the Visegrad Group on the Migration Crisis’, 15 October 2015, Permanent Representation of the Czech Republic to the European Union, https://mzv.gov.cz/representation_brussels/en/news_and_media/v4_declaration_on_the_migration_crisis.html; Aneta Zachová et al., ‘Visegrad Nations United against Mandatory relocation quotas’, Euractiv (23 July 2018), www.euractiv.com/section/justice-home-affairs/news/visegrad-nations-united-against-mandatory-relocation-quotas/.

4 Klára Votavová, ‘Imitation and Revolt. What the Visegrád Group Is and What It Could Become’, Heinrich Böll Stiftung Prague (28 June 2024), https://cz.boell.org/en/2024/06/27/imitace-revolta-co-je-co-mohla-byt-visegradska-skupina.

5 Róbert Gönczi, ‘Focus on Families and Migration Rationalization: The Visegrad Group’s Method’, Warsaw Institute, https://warsawinstitute.org/focus-on-families-and-migration-rationalization-the-visegrad-groups-method/.

6 ‘V4 Chambers of Agriculture Urge Brussels to Change Direction’, Hungary Today (25 June 2024), https://hungarytoday.hu/v4-chambers-of-agriculture- urge-brussels-to-change-direction/; ‘V4 Agricultural Chambers: a Change of Direction Is Needed in EU Agricultural Policy’, Trade Magazine (21 June 2024), https://trademagazin.hu/en/v4-agrarkamarak-iranyvaltasra-van-szukseg-az-eu-agrarpolitikajaban/; Marián Koreň, and Natasha Foote, ‘V4 Farmers Demand Postponement of New CAP Due to Ukraine War’, Euraktiv (8 April 2022), www.euractiv.com/section/agriculture-food/news/v4-farmers-demand-postponement-of-new-cap-due-to-ukraine-war/.

7 For more on the Visegrad Fund, see www.visegradfund.org/about-us/the-fund/.

8 Votavová, ‘Imitation and Revolt’.

9 Vladimir Soldatkin, and Boldizsar Gyori, ‘Hungary Sticks to Russian Gas, US Calls It “Dangerous Addiction”’, Reuters (6 June 2024), www.reuters.com/business/energy/hungary-sticks-russian-gas-us-calls-it-dangerous-addiction-2024-06-06/.

10 Robert Tait, and Flora Garamvölgyi, ‘Viktor Orbán Wins Fourth Consecutive Term as Hungary’s Prime Minister’, The Guardian (4 April 2022), www.theguardian.com/world/2022/apr/03/viktor-orban-expected-to-win-big-majority-in-hungarian-general-election.

11 Joakim Scheffer, ‘US Embassy Denounces Hungary in Paid Advertisement Full of Half-Truths’, Hungarian Conservative (26 March 2024), www.hungarianconservative.com/articles/politics/us-embassy_ad_allegation_hungary_energy-diversification_russia_eu/.

12 ‘Czech Presidential Candidate Babiš Backpedals after “Anti-NATO” Comments Spark Ire’, Euronews (23 January 2023), www.euronews.com/2023/01/23/czech-presidential-candidate-babis-backpedals-after-anti-nato-comments-spark-ire.

13 Mathieu Pollet, ‘Slovak PM: Ukraine Must Give up Territory to End Russian Invasion’, Politico (21 January 2024), www.politico.eu/article/slovakia-prime-minister-robert-fico-ukraine-cede-territory-russia-moscow-invasion-nato-entry/.

14 Tom Nicholson, ‘Ukraine Will Never Join NATO on My Watch, Says Slovakia PM Fico’, Politico (6 October 2024), www.politico.eu/article/nato-ukraine-slovakia-robert-fico-military-defense-alliance/.

15 Rikard Jozwiak, ‘The Visegrad Group: When 2 + 2 Doesn’t Equal 4’, Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty (27 February 2024), www.rferl.org/a/visegrad-hungary-poland-czech-slovakia-disunity/32837670.html.

16 Jozwiak, ‘The Visegrad Group: When 2 + 2 Doesn’t Equal 4’.

17 Jozwiak, ‘The Visegrad Group: When 2 + 2 Doesn’t Equal 4’.

18 Péter Szitás, and Anna Udvari, ‘Cooperation vs Confrontation: The V4 in the Shadow of the Russia–Ukraine War’, Hungarian Conservative (14 April 2024), www.hungarianconservative.com/articles/politics/cooperation_confrontation_v4_russia-ukraine-war_central-europe/.

19 Robert Beck, ‘The Visegrád Four: From Troubled to Broken’, Foreign Policy Research Institute (3 April 2024), www.fpri.org/article/2024/04/visegrad-four-from-troubled-to-broken/.

20 Adam Balcer, ‘More Than Independence: Poland and 1918’, Eurozine (7 January 2019), www.eurozine.com/more-than-independence/.

21 Oliver Krause, ‘Mackinder’s “Heartland”—Legitimation of US Foreign Policy in World War II and the Cold War of the 1950s’, Geographica Helvetica, 78/1 (28 March 2023), https://gh.copernicus.org/articles/78/183/2023/.

22 Lau Siu-kai, ‘The US Cannot Effectively Contain China’, China Daily (10 June 2024), www.chinadailyhk.com/hk/article/585307; Max Bergmann et al., ‘America’s New Twilight Struggle with Russia’, Foreign Affairs (6 March 2024), www.foreignaffairs.com/russian-federation/americas-new-twilight-struggle-russia; Seth G. Jones, ‘China Is Ready for War’, Foreign Affairs (2 October 2024), www.foreignaffairs.com/china/china-ready-war-america-is-not-seth-jones; Robert Kuttner, ‘Containing China’, The American Prospect (30 April 2024), https://prospect.org/economy/2024-04-30-containing-china/.

23 For more on the Three Seas Summit, see https://3seas.eu/.

24 Valerie Kornis, ‘Poland’s Perspective on the Three-Seas-Initiative’, Friedrich Naumann Foundation (25 April 2022), www.freiheit.org/central-europe-and-baltic-states/polands-perspective-three-seas-initiative.

25 ‘President Donald J. Trump on the 2018 Three Seas Initiative’, US Embassy in Romania (17 September 2018), https://ro.usembassy.gov/president-donald-j-trump-on-the-2018-three-seas-initiative/; ‘Remarks by Antony J. Blinken, Secretary of State, on the Three Seas Initiative Summit, 20 June 2022’, www.state.gov/three-seas-initiative-summit/; ‘Resolution Supporting Three Seas Initiative Unanimously Passes US House of Representatives’, Three Seas Summit (18 November 2020), https://3seas.eu/media/news/resolution-supporting-three-seas-initiative-unanimously-passes-u-s-house-of-representatives; ‘US Secretary of State Antony Blinken Expressed US Support for the Three Seas Initiative’, Three Seas Summit (11 February 2021), https://3seas.eu/media/news/us-secretary-of-state- antony-blinken-expressed-us-support-for-the-three-seas-initiative; Anthony B. Kim, ‘3 Seas Initiative: America’s Opportunity in Europe to Advance National Interests’, The Heritage Foundation (21 October 2022), www.heritage.org/europe/commentary/3-seas-initiative-americas-opportunity-europe-advance-national-interests; Daniel Kochis, ‘The Three Seas Initiative Is a Strategic Investment that Deserves the Biden Administration’s Support’, The Heritage Foundation (18 February 2021), www.heritage.org/europe/report/the-three-seas-initiative-strategic-investment-deserves-the-biden-administrations.

26 Vadim Shtepa, ‘Responding to Moscow’s Imperial Revanchism, a “Post-Russia” Forum Is Born’, The Jamestown Foundation (10 August 2022), https://jamestown.org/program/responding-to-moscows-imperial-revanchism-a-post-russia-forum-is-born/.

27 ‘Vladimir Putin’s Interview with Tucker Carlson, 9 February 2024’, Kremlin.ru, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/73411.

28 Anna Ohoiko, ‘How Similar or Different Are Ukrainian and Russian Languages? History, Numbers, Examples’, Ukrainian Lessons (16 November 2020), www.ukrainianlessons.com/ukrainian-and-russian-languages.

29 Marcin Piatkowski, Europe’s Growth Champion: Insights from the Economic Rise of Poland (Oxford University Press, 2018); Adam Biliński, ‘Biliński on Piatkowski, Europe’s Growth Champion: Insights from the Economic Rise of Poland’, H-Poland, (December 2021), https://networks.h-net.org/node/9669/ reviews/9449899/bili%C5%84ski-piatkowski-europes- growth-champion-insights-economic-rise.

30 See ‘GDP per Capita 1990–2022’, as shown in Our World in Data, https://ourworldindata.org.

31 Ufuk Akcigit, and Somik Lall, ‘From Shadows to Sunrise: How to Overcome the Middle-income Trap’, World Bank Blogs (23 September 2024), https://Blogs.Worldbank.Org/En/Developmenttalk/ From-Shadows-To-Sunrise-How-To-Overcome-The-Middle-Income-Trap.

32 ‘Błaszczak: Będziemy mieć najsilniejsze wojska lądowe w Europie, w ramach NATO’, Rzeczpospolita (28 July 2022), www.rp.pl/polityka/art36772481-blaszczak-bedziemy-miec-najsilniejsze-wojska-ladowe-w-europie-w-ramach-nato.

33 ‘Ćwiczenia Puma-22. Morawiecki: Musimy budować armię tak silną, żeby swoja siłą odstraszała wroga’, Polsat News (9 November 2022), www.polsatnews.pl/wiadomosc/2022-11-09/cwiczenia-puma-22-morawiecki-musimy-budowac-armie-tak-silna-zeby-najlepiej-nie-musiala-walczyc/.

34 Matthew Karnitschnig, and Wojciech Kość, ‘Meet Europe’s Coming Military Superpower: Poland’, Politico (21 November 2022), www.politico.eu/article/europe-military-superpower-poland-army/.

35 Paul Jones, ‘Poland Becomes a Defense Colossus’, CEPA (28 September 2023), https://cepa.org/article/poland-becomes-a-defense-colossus/.

36 Jones, ‘Poland Becomes a Defense Colossus’.

37 Marcin Zaborowski, and Kerry Longhurst, ‘America’s Protégé in the East? The Emergence of Poland as a Regional Leader’, Friedrich Ebert Stiftung (2003), https://library.fes.de/libalt/journals/swetsfulltext/18832068.pdf.

38 Zaborowski, and Longhurst, ‘America’s Protégé in the East?’

39 Zaborowski, and Longhurst, ‘America’s Protégé in the East?’

40 Zaborowski, and Longhurst, ‘America’s Protégé in the East?’

41 Karnitschnig, and Kość, ‘Meet Europe’s Coming Military Superpower: Poland’.

42 ‘Lecture of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán at the 33rd Bálványos Summer Free University and Student Camp’, Cabinet Office of the Prime Minister of Hungary (27 July 2024), https://miniszterelnok.hu/en/speech-by-prime-minister-viktor-orban-at-the-33rd-balvanyos-summer-free-university-and-student-camp/.

43 Tilak Doshi, ‘As Europe Deindustrializes, Can Economic Suicide Be Avoided?’, Forbes (10 May 2024), www.forbes.com/sites/tilakdoshi/2024/05/09/as-europe-deindustrializes-can-economic-suicide-be-avoided/; Carlos Roa, ‘Something Is Wrong with Europe’, Hungarian Conservative (12 February 2024), www.hungarianconservative.com/articles/opinion/crises_ukraine_october-7_red-sea_broken-european-strategy_opinion/.

44 ‘Lecture of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán at the 33rd Bálványos Summer Free University and Student Camp’.

45 Joakim Scheffer, ‘Hungary Calls for the “Cooperation of Sovereign States”—Could It Work?’, Hungarian Conservative (7 March 2024), www.hungarianconservative.com/articles/politics/hungary_austria_serbia_slovakia_cooperation_ v4_illegal-migration_war-in-ukraine/.

46 ‘Lecture of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán at the 33rd Bálványos Summer Free University and Student Camp’.

47 Nikolas K. Gvosdev, ‘Keystone States’, in United States: The Giant Challenged, Horizons: Journal of International Relations and Sustainable Development, 5 (Autumn 2015), 104–123, www.jstor.org/stable/48573591; Carlos Roa, ‘Between East and West: The Prospect of Hungary as a Keystone State’, Hungarian Conservative, 2/5 (2022), 60–67, www.hungarianconservative.com/articles/current/between-east-and-west-the-prospect-of-hungary-as-a-keystone-state/.

48 Balázs Orbán, Hussar Cut: The Hungarian Strategy for Connectivity (MCC Press, 2024).

49 Roa, ‘Between East and West’.

50 Nikolas K. Gvosdev, ‘Azerbaijan and the Global Position of the Silk Road Region’, Baku Dialogues (Autumn 2024), https://bakudialogues.ada.edu.az/articles/geopolitical-keystone.

51 A. Wess Mitchell, The Grand Strategy of the Habsburg Empire (Princeton University Press, 2018).

52 Viktor Orbán, ‘“The Conditions of a Stable Economic Policy Are in Place.” Speech at the Hungarian Chamber of Commerce and Industry’, 4 March 2024, https://miniszterelnok.hu/en/conditions-of-a-stable-economic-policy-are-in-place/.