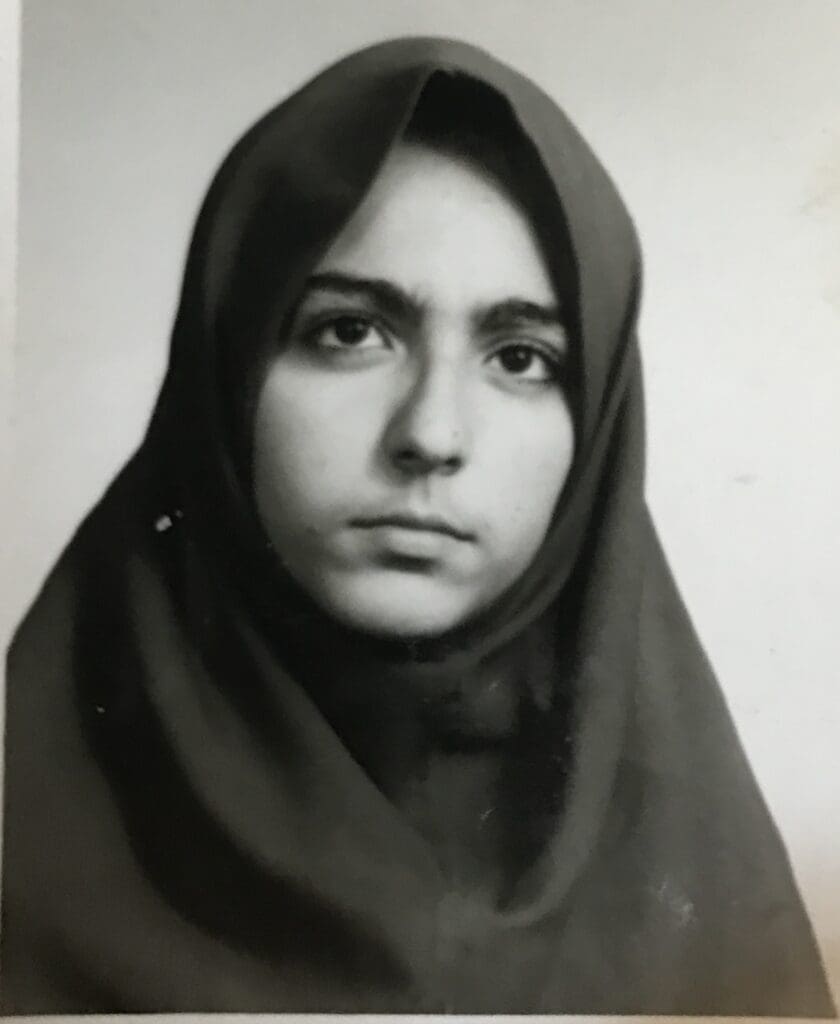

‘Christians in the Middle East are sacrificing their lives to preserve their faith and identity,’ Juliana Taimoorazy, an Assyrian Christian activist reminded us in the interview she granted to Mandiner. Taimoorazy is the founder and president of the Iraqi Christian Relief Council and a 2021 Nobel Peace Prize nominee, who even made the hit list of the Islamic State. We asked her about the tragic stories of the persecution of Christians in the Middle East and the turns of fate she and her community have experienced.

We spoke with Juliana Taimoorazy at the Danube Institute’s conference on Christian persecution.

How do you say ‘Good morning, have a nice day’ in Assyrian?

Qedamta Brihkta, Yoomoukh Brikha.

Do you consider yourself a descendant of the ancient Assyrians in any way—based on the Assyrian language, ancestry, genetics or culture?

I am ethnically Assyrian and speak the modern Assyrian language, which is a mixture of Aramaic and Akkadian. There is a still existing historical train of thought according to which the Assyrians of today are not the descendants of the ancient Assyrians—however, this idea is false. Ancient Greek and Roman scholars already found evidence that the Assyrians had lived in their own ancient territory without interruption for centuries, and recently Vatican researchers have established the same. Muhammad concluded a treaty with the Assyrians, which protected them from the persecution of the Muslims—because the Assyrians were already Christians at the time. The document itself proves that they were still living there in the 7th century, unchanged—and have continued living there ever since. We are the descendants of the ancient Ninevites who converted to the God of Israel after they listened to the preaching of Jonah in the 8th century BC. During the centuries, however, most of the Assyrians have scattered around the world as a result of persecution.

Your people are also referred to as Chaldeans. Is it a synonym or not?

If we look at it from a historical perspective, it is important to know that the Assyrians adopted Christianity and became Catholics early, and they were given the name ‘Chaldean Church’ by the Vatican. At the same time, there was an ancient Chaldean people as well, whose origin is still the subject of historical debates. I would say that we are all the children of Nineveh, we all speak Aramaic and have lived on the same land for centuries, so we are all siblings.

Nineveh is the modern-day city of Mosul, and if you look at the map, you will see that the ancient Assyrian lands are largely occupied by Iraqi Kurdistan today. The Assyrians had bitter historical conflicts with the Kurds, and, for instance in the Ottoman times, Kurdish tribes were responsible for the Assyrian genocide.

The Kurds are not indigenous in what is now Iraq. The Assyrians, the Yazidis and the Medes are the peoples of Mesopotamia, but the Kurds, on the other hand, only arrived here from the south-eastern part of Turkey about 8-900 years ago. During their migration to the south, they often occupied by force areas and settlements that had been long inhabited by other ethnic groups. Mosul was never and is still not a Kurdish city, the majority of its inhabitants are Sunni Arabs, and there are still many Assyrians living in the region, since this area used to be the territory of the old Assyrian empire. The name of the capital of the autonomous Kurdistan Region of Iraq, Erbil, which now has a Kurdish majority, also comes from the original Assyrian-Akkadian name of the settlement, Arbailu.

For centuries, the area was extremely diverse ethnically and religiously, but the Kurdish land grabbing has unfortunately made it more homogenous by today. However, there is a difference between the attitude of the Kurds and the Arabs. Throughout history—and in recent years, for example during the rule of the terrorist organisation Islamic State (ISIS)—, Arab Muslims harassed us primarily because of our religion, while the Kurds did so because of our cultural traditions and heritage.

The Kurds are determined to change the history of the area, they want to erase the Assyrian past from memory. The Erbil Citadel, for example, was an ancient Assyrian fortress, but now in schools it is taught that it is an ancient Kurdish castle.

The majority of the Assyrians have already left the land of their ancestors and live in the diaspora

There are two and a half million Assyrians in the world, the majority of whom are living abroad in the diaspora. In the United States, where I myself live, there are also about 400-500 thousand people of Assyrian-Chaldean-Syrian origin. The main reason for leaving for the West was that we can exist there as Christians.

The great wave of emigration started because of the Sayfo, the Assyrian genocide committed during World War I. However, by that time the multicultural environment that had characterised the old Assyrian territories for centuries had already broken down. What was the reason for that?

The Christian communities of the Middle East have suffered persecution from time to time and regularly since the beginning. The Zoroastrian Persians started it, and then the Muslims continued it. In the Ottoman Empire, Assyrian Christians were tolerated, they had territories and religious freedom, but at the same time lived as second-class citizens. Then, in the 18th century, Kurdish tribal leaders began to persecute the Assyrian and Armenian minorities in North-Western Iran and South-Eastern Turkey, and the ruling Turks used Kurdish militias to control the rebellious minorities.

The Sykes-Picot Agreement, which divided the Middle East into states, committed a huge injustice: it placed in the same state tribes and ethnicities that had never lived together historically and between whom there was no cohesive force. Then came the Iran–Iraq war, when the suffering of Iraq’s ethnic minorities was even further exacerbated.

The Assyrians adopted Christianity earlier than the Muslims appeared on their land. When did their situation become difficult?

Let me say something taboo-breaking: I think that the growing prejudice and suspicion of Muslims towards local Christians grew stronger after Western Christian missionaries appeared in the region.

After that, the Christian communities in the Middle East were seen as Western outposts

The same happened with al-Qaeda after 2003: the Muslim terror organisation justified the persecution of Christians by saying that the local Christians were the agents of President George Bush, as they said, ‘the relatives of the Americans.’ They questioned the loyalty of Iraqi Christians to their own state and government. Saddam Hussein was a bloody dictator, but, contradictorily, the authorities under his rule respected Christians. At the same time, they were persecuted by the regime not because of their religion, but because of their nationality—Saddam was pushing for the Arabisation of the country. The land of Iraq still hides a lot of undiscovered, old mass graves, many of them from the time of Saddam, as plenty of people were killed because of their ethnicity in those years.

You grew up in Iran. How strong was the Christian tradition among the Assyrians of Iran in your childhood?

The Assyrians have never denied their Christianity, they have been holding on to their faith. In the identity of the Assyrians, ethnicity and Christian faith have inseparably fused over the centuries. There was never a phase in my personal life either when the two separated. The Assyrians paid a very heavy price for their identity, so they treasure it very much. Let me give you an interesting example: there is an Assyrian minority living in Turkey too, but a part of them has become Muslim over the centuries. In recent decades, they have rediscovered their Assyrian roots, but in addition to ethnicity, the Christian faith is an inseparable part of this, so now there is a big debate in their circles about the fact that in order to restore their old identity, it would be necessary to abandon the Islamic faith and adhere to the Christian Assyrian tradition again.

You were six years old when the Islamic Revolution in Iran overthrew the previous regime. What is your recollection: was it a rapid change, covering all areas of life?

Absolutely. Before 1979, there was freedom of religion in Iran, at least in the big cities, because religious fanaticism had always been present in the villages, which considered Christians infidels. However, everything changed with the revolution: almost from one day to the next we had to wear hijabs, and women could only leave their home if their clothing covered everything except for their faces and hands—the rule applied to everyone, including Christians. I remember I was six years old when we learned from the newspapers that the Shah had gone abroad; my mother started to cry—she knew what was coming. The followers of the ayatollah marched on the streets, celebrating with flowers, and we watched them standing at the doorstep. One of the marchers grabbed my mother by the throat and yelled ‘You filthy Christian, when your husband will no longer be with you, you know what will happen to you, don’t you?’ For Christians, these years were the most terrible in Iran’s history. Although Islamic radicalism later subsided, and my younger cousins, who are one generation younger than me, feel that life is now more tolerable, but it was different in my teenage years.

Every time we passed in front of our neighbours’ houses, they spat after us,

and at school they tried to persuade me to convert to Islam several times. I remember I was around thirteen when in one of the classes my teacher provoked a debate with me about the Holy Trinity, humiliated me, and then threw me out of the classroom. My parents made a complaint to the school and then to the ministry of education, but it was all in vain.

What was the turning point that made your parents decide to leave Iran?

My brother graduated from medical school in Tehran. When he was faced with the fact that he would not be allowed to practice as a Christian, since a Christian doctor could not examine a Muslim patient, we got fed up, and the family decided that we could no longer live there. For a long time, a year, my parents were looking for a human smuggler for my brother, and they succeeded in 1988: my brother was smuggled out of Iran, and he reached Germany, where he was finally granted political asylum.

In 1989, you followed his example. How were you be smuggled out of the country?

It was a very trying process. We sold everything in advance, of course secretly, so we stayed with a relative for three months and then in a hotel room for six months; we were waiting for the opportunity. One of the smuggling teams vanished with the large sum we gave them as an advance payment—they played us. The first serious smuggling offer was that I should be covered in sheepskins and taken across the border to India in a livestock transport.

There was a Baha’i lady who went for it, and no one ever heard of her again… The other offer was that a Muslim man would marry me, all references to my Christian status would be deleted from my documents, and I would be taken to Germany in a chador. In this case, however, it would have been difficult to legally divorce afterwards. The third version was, and this is what eventually happened, that we obtain a forged visa with an invitation to a fictitious seminar in Switzerland. Me and my parents managed to travel out of the country with false papers; my father got a German visa but my mother and I had a Swiss one, so another smuggler from Switzerland took us to him to Germany. We crossed the German border illegally, because the border guard knew the smuggler, then we continued by train and finally met my brother as well. We were granted asylum as refugees from religious persecution.

What was your first impression of the West?

Liberty. The smell of European coffee and freshly baked pastries when I first entered a coffee house—the first experience of liberty was accompanied by this scent experience, and it burned into me. The smell of liberty. My mother experienced liberty for the first time differently: she was relieved when our plane left Iranian airspace.

Can you ever return to Iran?

I am not allowed to go back.

I am an outspoken critic of the Iranian regime as a public figure—this precludes my returning unharmed.

I regularly raise my voice for the suffering not only of Iranian Christians, but also of Iranian women, the local Jewish community, and ordinary Iranian people.

In the case of the Khashoggi murder, we saw how the Saudi government treats its outspoken critics, and we also know about the imprisonments that the Iranian dissidents returning to Iran are sentenced to. Have you received threats because of your activities?

Naturally. But I do not know whether these threats are directly linked to the Iranian regime.

However, there is evidence that I was on the hit list of the Islamic State

I am a human, so there is a natural fear inside me because of these phenomena, but I also know that my calling to help persecuted Christians comes from God. I know that as long as I act in His calling, He will protect me. I do not have any security guards, so my enemies can get me if they want to. Several of my activist friends died under mysterious circumstances, and I also regularly receive threats, but that will not stop me from doing my job.

You are the president of the Iraqi Christian Relief Council. In what kind of activity is this organisation engaged?

In the last 15 years, we have taken a plenty of humanitarian relief supplies to Iraq for Christians in need. We have delivered food, medicine, tents countless times, and after the withdrawal of ISIS, we made aid available for the rebuilding of damaged houses. We provide educational grants, cover the costs of heart surgeries, the treatment of cancer patients, and so on. Iraq is my homeland. My ancestors lived there, and when I go there, I am always thriving. On the other hand, in the United States, where I live, 15 years ago only a small segment of society was aware of the fact that there is a significant Christian minority living in Iraq; we have raised awareness about this in America, and once they knew about it, Americans became more generous in helping those in need in Iraq.

What is the situation of Christians in Iraq now?

Tragic.

The Patriarch of Iraq told us a year ago that there is hope, as the situation is starting to improve.

Unfortunately not. Currently there is no functioning government in Iraq. Shiite cleric Muqtada al-Sadr is currently organising a movement to oppose Iranian influence—even though he is a Shiite leader. It is very difficult for Christians to find political allies in Iraq, as parties and politicians come and go.

There are five members of parliament who are willing to represent the interests of Christians, but they are under Iranian influence, too.

Thus, it is very difficult for Christians to raise their voice. By the way, the programmes of Hungary Helps were an enormous help in this passive environment. However, that is not enough, because Iraqi services are in a terrible state, the education and health systems are in a very run-down state.

Finally, what is your impression of the Western Church? While living a Christian life is life-threatening in some regions of the Middle East, Western churches are becoming empty, and Christianity is losing its moral pillars. How do you see our situation?

The West is struggling to maintain its own civilisation. Our world is falling apart, and so are our morals and our families. Churches become museums, monastery buildings are sold, and many abandoned churches in America are turned into mosques. 15 years ago, many of my American evangelical friends said to me, ‘you Assyrian Catholics are cultural Christians, you were baptised as babies, but your religiosity is empty.’

Well, however, the situation today has become such that it is America that is becoming culturally Christian

While American Christians engage in congregationalism and do not feel the weight of their faith, the Catholic Assyrians of the Middle East are even willing to lose their lives for Jesus and for their Christian faith; they are really living the gospel. And when persecution comes, they hold on to their faith even more. American Christians do not know suffering. To preserve Western civilization, we must remain faithful to Christ.

Click here to read the original article