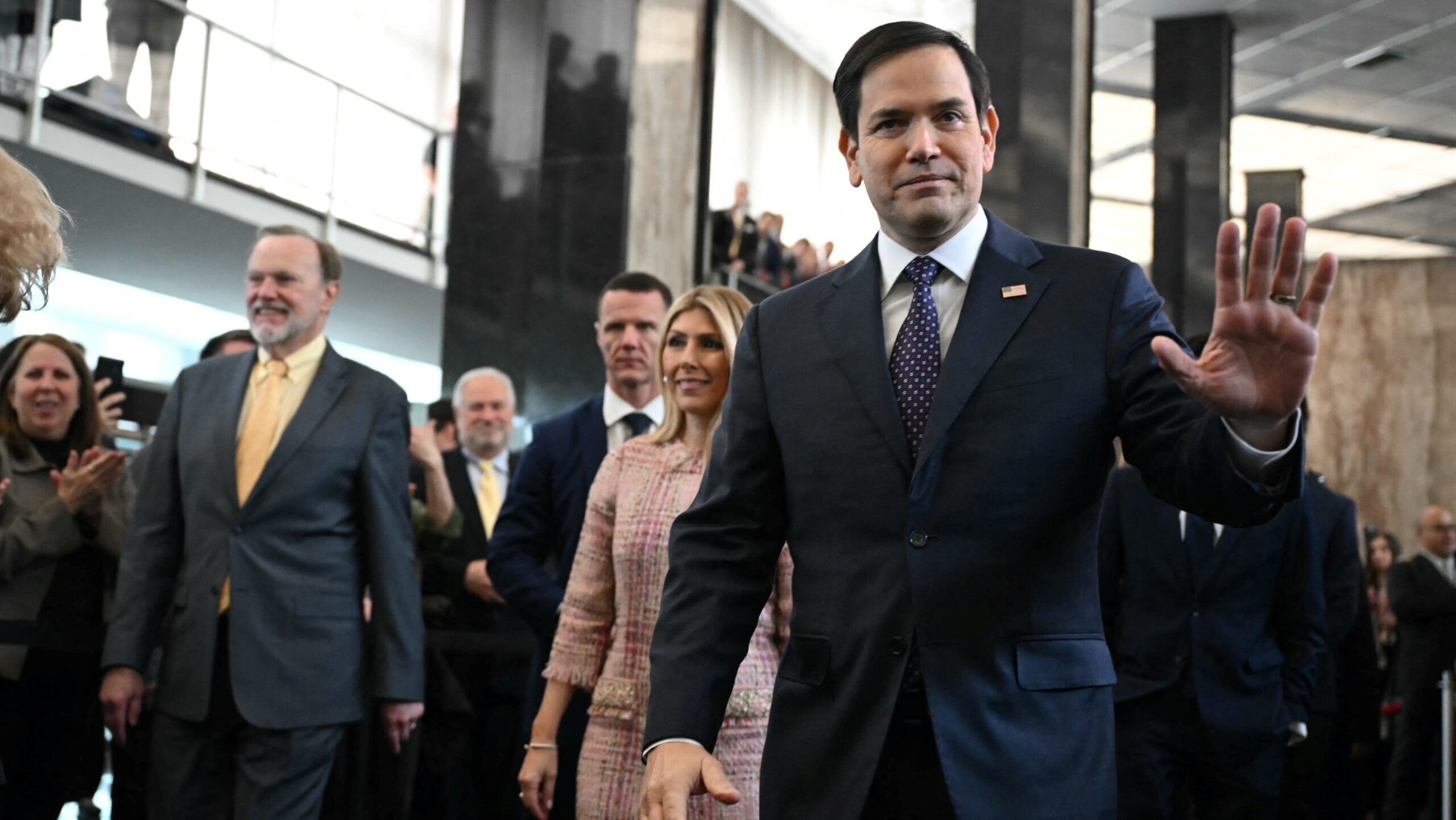

Many are familiar with the famous remark by late former US Secretary of State and National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger: ‘Who do I call if I want to talk with Europe?’ Kissinger’s comment referred to the power struggle within the European Union between its institutions, primarily the European Commission and the European Council, over which body should lead foreign relations. However, as the first days of Donald Trump’s second presidency demonstrate, Kissinger’s question does not seem to concern the new administration. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has made dozens of calls over the past week—none of them with European Union leaders.

Rubio’s early diplomatic engagements hint at the priorities of the new administration’s foreign policy and the regions it plans to prioritize. Unsurprisingly, these are the Indo–Pacific region and the Middle East. Rubio’s first major engagement was hosting a Quad meeting—a US-led defence alliance that includes Australia, Japan, and India—in Washington, DC. This was followed by calls with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, his counterparts in Indonesia and South Korea, and leaders from the UAE and Saudi Arabia.

Rubio Focuses on Member States, Not EU

It wasn’t until Rubio’s 15th call on 23 January that a European country entered the conversation: Poland, a traditionally strong US ally, particularly on security matters. Warsaw also currently holds the Presidency of the European Council. However, according to the State Department’s press release, no EU-related topics were discussed during Rubio’s call with Polish Foreign Minister Radosław Sikorski.

Rubio also called Hungarian Minister for Foreign Affairs and Trade Péter Szijjártó on 26 January, marking him as the fourth European leader he contacted—following his Lithuanian and Latvian counterparts. None of these discussions touched on EU-related issues. It is also notable that, in his first week, the Secretary of State did not contact France or Germany, the EU member states with the most influence over the bloc’s integration policies.

While there is already a sense of panic in Brussels over the second Trump administration’s apparent disregard for the EU—clearly reflected in an article by progressive mouthpiece POLITICO—, the sovereigntist forces across Europe could not be more pleased. Early indications suggest that Trump’s team prefers bilateral negotiations at the member-state level, rather than engaging with the EU as a unified bloc. This approach effectively eliminates coordinated pressure from Brussels and Washington on member states. In fact, the reverse seems more likely: member states, working with Washington, could place pressure on an increasingly isolated Brussels leadership, which appears disconnected from geopolitical realities.

No Reply

At the same time Brussels has continued to embarrass itself with increasingly desperate attempts to gain Trump’s attention, to no avail. According to Bloomberg, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen tried to arrange a meeting with Trump before his inauguration, but it never materialized. More recently, Kaja Kallas, the EU’s new foreign affairs chief, issued an open invitation for Secretary Rubio to attend a meeting of the bloc’s foreign ministers in Brussels on Monday. The response? None. Rubio left Kallas on read, did not attend the meeting, did not even responed. This constitutes a major diplomatic blunder for Brussels.

It is also telling that no EU officials were invited to attend the inauguration of President Trump. From the European Parliament (EP), right-wing representatives from groups such as Patriots for Europe (PfE), European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR), and Europe of Sovereign Nations (ESN) were present at the ceremony, while establishment and progressive factions were notably absent. According to POLITICO, some EP lawmakers are also attempting to establish connections with the new US administration, but their efforts, apart from those of the right-wing groups, have yielded little success.

President of the European People’s Party (EPP) Manfred Weber expressed frustration over the situation, stating that it is unacceptable for the Patriots to be the sole European partners of the new US administration. ‘We must again interlink with our American partners on a lot of issues,’ he declared. Weber’s desperate plea is particularly ironic given that just three months ago, he claimed in Strasbourg that Hungary was isolated in the Western community and that no one wanted to negotiate with Prime Minister Viktor Orbán.

Drain Down the Swamp

Even before Trump’s return to the White House, there was significant anxiety in Brussels over how EU officials could secure a line of communication with him. Trump’s campaign centred on promises to Americans that he would take on the deep state and the establishment in Washington—a process he has already begun. The very same establishment Trump is fighting against in Washington is entrenched in Brussels, pursuing the same globalist objectives. This is fundamentally incompatible with Trump’s views, therefore, not much can be expected regarding the improvement of relations.

The fact that the EU leadership is not only incapable of cooperation but also unable to establish basic communication is concerning—though not entirely surprising. Relations between the United States and the European Union could easily deteriorate, potentially over issues such as a proposed US purchase of Greenland or the outbreak of a trade war. Trump has already signalled his dissatisfaction with how Europeans treat the US and has hinted at imposing tariffs on EU trade.

‘The very same establishment Trump is fighting against in Washington is entrenched in Brussels, pursuing the same globalist objectives’

It increasingly appears that the responsibility for avoiding such scenario and maintaining good relations with the US will fall to individual member states. Some have even suggested that Viktor Orbán could serve as a potential mediator between the EU and Trump. Italy’s Giorgia Meloni is another candidate in this regard. Trump’s presidency, in this context, may also aid member states in ‘draining the swamp’ in Brussels, helping to weaken the globalist establishment not only in Washington, but in the EU’s capital as well.

As foreign policy potentially shifts back to the control of member states, Brussels could face more than just humiliation—it could suffer a significant loss of influence over its members. This development might eventually pave the way for a more pragmatic European Union, moving away from the current overly ideologized approach to policymaking.

Related articles: